Manuf. Specs.:

Dimensions: 17 1/4 in. W x 3 1/2 in. H x 12 1/2 in. D (43.8 cm x 9.8 cm x 30.8 cm).

Weight: 25 lbs. (11 kg).

Price: $3,495.

Company Address: c/o Madrigal Audio Laboratories, P.O. Box 781, Middletown, Conn. 06457; 860/346-0896.

As a high-end audio brand, Proceed's pedigree is pretty close to unimpeachable. While its sister brand, Mark Levinson, cannot be said to have literally invented esoteric audio as we know it today, to many of us who cut our audio teeth in the 1970s, it almost seems so. Today, Mark Levinson is a division of Madrigal Audio Labs, as is Proceed; Madrigal in turn resides among the extended audio family gathered under the wide-reaching umbrella of Harman International.

In essence, Proceed functions as Madrigal's "entry-level" brand, if a line whose least costly CD player, the $3,500 CDP under scrutiny here, can be considered entry level. Yet the standards to which even this "junior" brand is held are immediately evident: The CDP is beautifully crafted, with a distinct industrial design that should prevent it from ever being confused with the latest flagships of any of the big brands.

Exterior surfaces are all aluminum plates or extrusions, very nicely done up in gun-metal gray or milky brushed finishes with a subtle, sculptural variety of textures. The net effect is something I suspect observer will either love or hate; I find it quite smashing despite the purple logo plate which is perhaps a bit over the top.

Front-panel controls are well spaced and simple, with the usual transport and programming keys represented along with several LED indicators, including one to de note playback of HDCD-encoded discs since the CDP incorporates HDCD decoding circuitry. There are also two good-sized LED displays, one oblong and one round Panel graphics are nicely legible black on white, and, aside from their rigorously cummings-esque typography, are perfectly straightforward.

Disc timing data comes up in the oblong display, while the round window is reserved for track number; both are eminently read able. You can call up elapsed or remaining track or disc times from the front panel or the remote. The CDP's disc drawer is unique: a dramatically slim slab of aluminum barely 1/2-inch thick, machined with concentric depressions for 5- and 3-inch CDs. The drawer's effect while open is striking; when it's closed the hairline front edge contributes to the Proceed's very contemporary look.

On the back, the CDP's jack panel is somewhat unusual for a CD player. There are both RCA unbalanced and XLR balanced analog outputs, as well as a coaxial (RCA-jack) S/PDIF digital output, a grounded IEC power-cord receptacle, and a pair of 1/2-inch jacks, one an infrared-repeater input and the other a DC-trigger turn-on output. So far, not so singular but the CDP also supplies a pair of digital inputs, one coaxial and the other Toslink optical, which can be set to feed its internal D/A converter.

Proceed's reasoning seems very sound: The CDP could contain the most accurate D/A converters of all the digital components in many systems, so why not make them available for use with laserdisc players, MiniDisc recorders, or other digital sources whose internal chips might hold less sonic potential? And because the CDP can be configured for variable-level output with remote-controlled volume, it can function as a very simple, digital-input-only preamp, not at all a bad concept for maximizing potential value.

Inside, the CDP is every bit as handsome as its exterior might suggest. (In fact, when not listening to the Proceed player, you could remove the top cover and hang it on the wall.) A single circuit board occupies the right-hand two-thirds of the case, which contains top-grade parts: a very substantial toroidal power transformer, extensively regulated and filtered power supplies, and some prominent LSIs, including the HDCD chip and a Motorola processor. The left-hand side is occupied by a ruggedized Philips CDM12 industrial CD-ROM transport mechanism.

The D/A converter and audio sections are laid out in fully dual-mono fashion, with a separate Analog Devices AD1864 dual-18-bit converter for each channel.

Digital-domain processing and filtering are performed with 24-bit precision by the HDCD chip. The CDP is not an all-discrete circuit, the sort so popular with high-end designers; instead, its output stages include several high-grade audio ICs.

Proceed's documentation explains that the CDP maintains fully balanced design in both the digital and analog domains (and immediately balances the auxiliary digital inputs), to reduce noise and distortion throughout. An unconventional closed loop design places the master reference clock electrically just before the D/A circuits and slaves both the transport and the DACs to it, which is said to reduce jitter dramatically. Proceed also touts the stability of the CDP's fully digital servo systems, which it says will not require calibration, even after several years of use, to maintain optimum performance.

The supplied remote control is a workaday design-probably an off-the-shelf unit (it's marked "Made in Malaysia"). It has a number of useful features but is not really up to the level of the CDP itself in terms of ergonomics, design, or feel. Keys are quite cramped, and although Proceed has taken pains with button color and grouping, readability and "by-feel" learnability are less than wonderful. The remote has all the expected CD control and programming commands and adds a "Polarity" key that inverts the signal at the outputs. It also adds a rather unexpected group of controls: "Source," volume "Up" and "Down," and "Mute." These are for the CDP's aforementioned preamp functions.

The two digital inputs are selected by keying the "Source" button once or twice; the player will revert to its own transport's signals if you re key play or open or close the drawer. The volume and muting keys are normally inactive; to activate them for external sources and for the CDP's own playback, you first perform a customizing routine by holding down certain front-panel buttons. In addition to activating the level controls, you can select a volume-display mode, choose a muting level, and set the player to revert to standby mode after 5 to 60 minutes of inactivity. There's also a left/right balance routine accessible from the remote.

Rather unusually, the CDP contains not only an infrared receiver but an IR transmitter as well. This enables it to send out its full complement of commands (which is considerable) to a full-system learning remote control, multi-room controller, or other media controller device. The library of codes includes all the CDP's native operational commands, plus a number of what Proceed terms "positive" controls: commands that induce a particular response regardless of the CDP's current state, as opposed to "toggling" a particular mode. For example, the front-panel drawer button will open the drawer or close it, depending on current position, but the CDP also stores separate "positive" commands for each action as well as for power on, standby, external-source selection, play, pause, stop, and several other functions.

The reason for providing such commands is to facilitate control of whole-house media systems, since when commanding a component from a remote room you don't necessarily know what state it is in (whether it is on or off, for example). These commands also make programming the "macro" keys found on many powerful, full-system learning remotes simple and useful; given my ambivalence toward the CDP's own remote, if I owned the Proceed I might well avail myself of one.

Measurements

Bench-testing the Proceed CDP was for the most part routine, in the best sense: Its performance was consistent, predictable, and almost uniformly superb. I made all tests using both the balanced and unbalanced outputs but will compare results only in the few cases where they diverged in some significant way.

Frequency response, shown in Fig. 1, is very flat and smooth, even on this expanded vertical scale, drooping barely 0.2 dB at 20 kHz and offering almost no visible evidence of filter ripple. Channel balance is almost spot-on at 0.1 dB, which is very good, but somewhat unexpectedly it was better from the unbalanced outputs, at less than half this figure. The unbalanced RCA outputs produced identical overall response, and both sets of outputs supplied exceedingly low source impedances (22 ohms balanced, 14 ohms unbalanced), which will keep cables or input impedances from being much of a factor sonically.

Fig. 1--Frequency response.

Fig. 2--THD + N vs. frequency at 0 dBFS.

Fig. 3--THD + N vs. level at 1 kHz.

Fig. 4--Channel separation.

Figure 2 displays total harmonic distortion plus noise (THD + N) versus frequency at 0 dBFS, and it is low indeed over the entire spectrum. Adding a 20-kHz "brick wall" filter to the test loop reduced top-octave THD + N by about two-thirds (not shown), but it was already low enough that this hardly seemed significant.

Fig. 5--Spectrum analyses for on "infinity-zero' signal and a 1-kHz tone

at-60 dBFS.

Fig. 6--Deviation from linearity at 1 kHz.

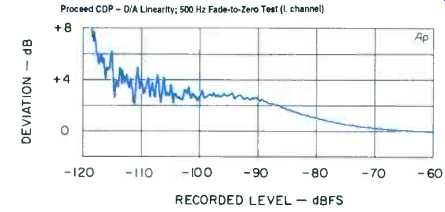

Fig. 7--Fode-to-noise test, dithered 500-Hz tone.

Besides XLR and RCA analog outputs, the CDP has digital outputs and inputs.

Distortion at 1 kHz, measured as a function of signal level, is nearly as impressive (Fig. 3). The CDP reproduces very low-level signals with no observable penalty in noise or distortion, and its rendition of full-scale signals is equally satisfactory. Signal-to-noise ratio was also superb, with a slight (3 dB) advantage to the balanced outputs. Dynamic range, as measured by the EIAJ standard of exercising the D/A circuit with a -60 dBFS tone, was within a couple of dB of the very best I've seen.

Figure 4 shows channel separation (crosstalk) in both directions. Better than 110 dB at all frequencies between 100 Hz and 16 kHz, this is exceptionally good, as is the match between channels. The jury is out on whether or not this kind of separation really matters, but it's hard to argue with the level of care in board layout and component selection that it suggests.

Figure 5 shows two different plots of the CDP's noise spectrum (referred to full-scale output), one for an "infinity-zero" silent track and the other while reproducing a -60 dBFS 1-kHz tone. In both cases the consistency between channels is notable, as is the freedom from any discernible power line harmonics (the blip at 5 kHz may be pollution in the test environment). The rolloff above 80 kHz, almost precisely 18 dB/octave, is welcome, as among other things it suppresses any possible contamination of the output by clock leakage.

Digital-to-analog conversion accuracy, represented by deviation from linearity at low levels, is depicted by two plots. Figure 6 actually combines two tests: undithered 1 kHz tones from 0 to -80 dBFS and dithered tones from -80 to -100 dBFS. The positive error evident over the latter range, though negligible in absolute terms, is greater than I might have expected given the CDP's excellent precision elsewhere. The same can be said for Fig. 7, the fade-to-noise test with a dithered 500-Hz tone (only one channel is shown, as the two were effectively identical). The same magnitude of error is evident, but here we can see that it shelves, maintaining a roughly 3-dB deviation until becoming "lost in the grass." This looks suggestively like some sort of 1-bits-worth error in the push-pull DAC configuration, especially since it was consistent for both channels.

I cannot say that during my auditions (completed before any bench testing) I heard anything but superb low-level resolution and excellent pitched and ambient decays from the Proceed; both can be telltales of linearity errors. But then I've never claimed to be able to hear a few decibels worth of deviation some 90 dB down!

Use and Listening Tests

I'm not convinced of the necessity for balanced line connection in home hi-fi systems, but since push-pull operation is so central to the CDP's design I opted to preserve it straight through to the amplifier. I connected the Proceed player to two channels of a Ginepro 3000x6 power amp, a six channel (at 350 watts each) bipolar solid-state design of exemplary performance, using the amp's XLR inputs and a pair of pro-quality, 12-foot microphone cables. The Ginepro drove B&W Matrix 803 Series 2 speakers.

Rather than using the CDP's volume control, I kept the player set to its fixed-level mode for most of my auditioning, on the theory that this would preserve the greatest signal purity. This required using the power amp's front-panel input attenuators as volume trims, a discipline to which I quickly grew accustomed, even finding that it tended to help focus my listening somewhat.

(I'm not saying I'd want to live this way permanently, though.) I was quickly made aware that this stripped-down setup produced playback of a very high level. Sounds materialized from a perfectly "black," dead-silent background, and they seemed more than usually solid, present, and out in the room. The Proceed was entirely free of bass exaggeration or any extra warmth or punch, yet the combination yielded about the best-controlled, most-effortless bottom octaves I've heard the B&Ws deliver. At the same time, the Proceed sounded open, detailed, sharply defined, and transparent-but not particularly airy in any highlighted way.

The CDP never sounded soft, however; in fact, if I had to characterize it at all I'd lean toward infinitesimally brighter, or clearer, rather than darker or warmer.

Piano recordings shone especially. A Sheffield Labs disc of Schubert pieces for four hands (Sheffield 10054-2-F), by the Piano Duo Schnabel, sounded dramatically present but not very "recorded" at all, in good measure because of its very homey, un-dramatic production. The CDP managed to etch transients without sounding cold or electronic, and the disc's very up close piano resonance, hammer "tonk," and room sound were subtly portrayed.

I cannot lay claim to an extensive collection of HDCD-encoded discs, but I do have Reference Recordings' two samplers. These include several stunning tracks. The version of Miles Davis's "All Blues" from the first volume (Reference's RR-S3CD) played via the CDP was marvelously clear, lively, and subtly dynamic, with truly sit-up-and-notice drum sound, especially the cymbal rides. All of the pieces from the second sampler volume (Reference RR-905CD) were sonic standouts. The movement from the Janácek Sinfonietta demonstrated the CDP's ability with complex, dynamically demanding music and bigger-image recordings, though I found this track a shade bright-sounding for a hall recording.

Speaking of imaging, the CDP did not project the sort of highlighted stereo soundstage you sometimes hear from esoteric systems, but it did create a very believable image. The CDP produced a pleasant illusion of depth, mostly behind the speakers, and was exceptionally solid and stable in its placement of instruments and voices.

I also found an HDCD-encoded recording of a more commercial, if not exactly mainstream, genre: Big Mama's Door (OKeh BK-67593), by the remarkable young folk/blues-man Alvin Youngblood Hart. This disc sounded electrifyingly in-room--warm, lifelike, and intimately live.

The net effect was eerily that of being transported to the San Antonio hotel room where Robert Johnson cut his most famous sides, but with better fidelity--if you can imagine a live-to-digital two-track session in Depression-era Texas.

How much of this sonic excellence was due to the Proceed's intrinsic goodness and how much to the HDCD system, I am not prepared to say. I don't have enough experience with HDCD players and discs, and in any event, the CDP sounded equally fine, or as nearly so as to call the matter into question, on numerous non-HDCD discs.

==========

MEASURED DATA

Line Output Level, 0 dBFS: Balanced, 2.5 volts; unbalanced, 4.5 volts.

Line Output Impedance: Balanced, 22 ohms; unbalanced, 14 ohms.

Channel Balance: Balanced, ±0.05 dB; unbalanced, ±0.025 dB.

Frequency Response: +0.1,-0.2 dB, 10 Hz to 20 kHz.

Channel Separation: Greater than 102 dB, 125 Hz to 16 kHz.

THD + N at 0 dBFS: Less than 0.004%, 20 Hz to 20 kHz; 0.0015% at 1 kHz.

Maximum Linearity Error: Undithered recording, +1.4 dB at-80 dBFS; dithered recording, +3 dB at -100 dBFS.

A-Weighted S/N: Balanced, 113 dB; unbalanced, 110 dB.

Quantization Noise: -97.1 dBFS.

Dynamic Range: 99 dB, A-weighted.

=========

Regarding more mundane issues, I have little out of the ordinary to report. The player worked silently and exceptionally smoothly. It has a two-speed drawer mechanism that slows down as it closes--very slick--although it takes its time to load and cue a disc (about 7 seconds). The CDP's ultra-elegant disc drawer is also quite sharp cornered; even though its edges are slightly eased, you can still give yourself a scratch if you accidentally drag the back of your hand across a corner.

The passage of time did not engender any warmer feelings toward the CDP's remote control. Its graphics are somewhat confusing, its lettering doesn't provide enough contrast for good readability, and its placement of the fundamental transport keys, crammed together at the top edge, was unfortunate-to my fingers anyway. Oh, well; this is what programmable master remotes are made for.

The CDP proved very regular and reliable, with only a couple of hiccups over a two-week period. First, when fast-searching through a disc, the player would occasionally jump ahead 10 seconds or so from the expected release point. Second, walking across the carpet, touching the player, and discharging a bolt of static occasionally induced an audible "tick" over the outputs, and once it caused the CDP to go all aphasic and revert to stop mode; re-keying play returned everything to normal.

All in all, the Proceed CDP is an exceptionally fine CD player-one of the two or three best-sounding (and handsomest) I've used. Its price is steep, but no more so than that of many another high-end design. And the Proceed has the very unusual added value of digital inputs and preamp utility. Certainly those in search of a top-flight CD player and D/A converter with heirloom quality materials and construction owe it a serious audition.

-Daniel Kumin

=================

(Adapted from Audio magazine, Jun. 1997)

Also see:

Proceed PCD CD Player and PDP D/A Converter (Auricle, Apr. 1991)

Philips LHH 500 CD Player (Apr. 1992)

= = = =