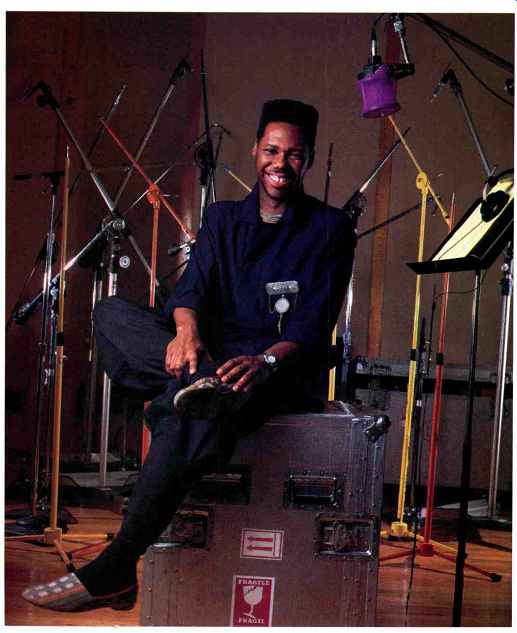

Nile Rodgers may be the hottest and the hippest producer on the pop music scene today.

He could probably claim that title simply on the basis of his production of Madonna's smash-hit LP, Like a Virgin. But his credits also include a list of extremely commercial yet hardly mainstream hits such as David Bowie's Let's Dance, Mick Jagger's solo-debut album She's the Boss, which he co produced with Bill Laswell, and "The Wild Boys" single for Duran Duran. He has also produced records for Diana Ross, Jeff Beck, Peter Gabriel, Debbie Harry, Johnny Mathis, Inxs, Kim Carnes, and Sister Sledge.

In addition to his impressive record as a producer, Rodgers is one of the most sought-after session guitarists around, and in fact he says he primarily thinks of himself as a jazz guitarist. He can be heard on many of the records he's produced, and on others such as Hall and Oates' Adult Education and The Honeydrippers' EP. Rodgers' greatest success as a musician came when he teamed up with friend and producing partner Bernard Edwards to form the group Chic in 1977. The group's first single, "Dance, Dance, Dance (Yowsah, Yowsah, Yowsah)" went gold. Chic's second album, which went double platinum, contained the single "Le Freak," one of the biggest hits of the disco era. The third record also went platinum, in 1979. Rodgers' latest solo album, B-Movie Matinee, was released earlier this year by Warner Bros.

-T.F.

----

I wish I had known you were in the house band at the Apollo Theatre when 1 was doing my book on the Apollo; I would have interviewed you then. How did you end up there?

I was working for Sesame Street and Loretta Long. Her husband was Peter Long, and he was the manager or something at the Apollo.

Yeah, he was the PR guy.

Ah, so now I know what he really did.

When the Apollo was looking for a guitar player who could read, Loretta said, "Hey, why don't you try Nile out, he seems to be really great with the Sesame Street stuff, so check him out." I did the first job and they liked me at the Apollo, so I stuck around. I guess I was around 19 because everybody was going to the Manhattan School of Music. This was the early '70s, right there at the end, when the whole thing [at the Apollo] was starting to wind down.

They started booking other stuff in there. It got weird .... I'm sure I did some of the last few gigs there.

What kind of music were you listening to then?

At that time it was jazz, basically. A lot of rock 'n' roll. Blues. The thing is, I had been into rock 'n' roll and blues and stuff earlier, so of course I continued to listen to it. But at that time in the '70s I was more fascinated with jazz. When I was working at the Apollo I had money, so I could buy any record at that point.

That's interesting because we're about the same age, and that's when I started to get into jazz, too. In the early '70s rock 'n' roll seemed to be getting pretty boring.

Yeah, it was getting boring. Especially after Hendrix, and because of the politics and stuff. It didn't seem to have that color and that flare it had when Hendrix .... You know, a lot of people died around the same time, too. And even if you weren't a big Doors fan or a big Joplin fan or whatever, still just the impact of it all happening around the same time seemed like, "Damn, this isn't the right stuff!"

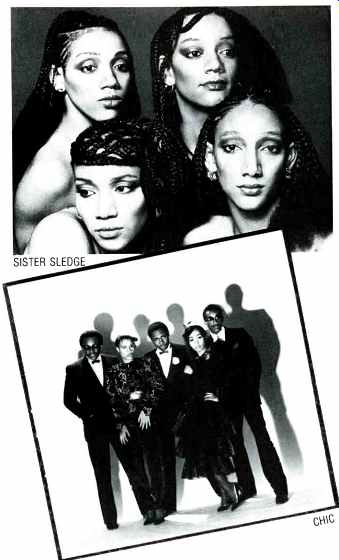

You were at the forefront of the disco movement with your group Chic in the '70s, and with your production of groups like Sister Sledge. I wonder if this turn away from rock to jazz had any direct impact on the way disco developed as a sound.

Disco was always a sort of ambiguous category to me in those days. I thought that disco meant anything you wanted to do as long as the drums went [he mimics a fast drumbeat]. That's what I thought. So what we did in Chic was basically play jazz. My first records, my own stuff, my compositions or the record dates where I was in charge, we basically did updated versions of jazz songs. The first formal arrangement I did was "Bess, You Is My Woman Now." Then we did "Air Mail Special." And we got a lot of really great players together and we went in and did disco records, but we were playing jazz. We were playing all the changes. We just changed the beat and the groove around.

So there was a connection between the jazz you were listening to and the disco you were playing?

Oh, absolutely. We wanted to be known as players, so when we decided to play pop music we thought all we had to do was take really great jazz songs-because we loved the melodies, we loved the heads-and just play those and give them a funky feeling and they'd be happening.

You once said you turned to disco out of necessity. What did you mean by that?

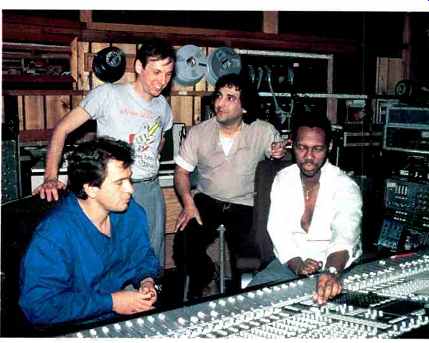

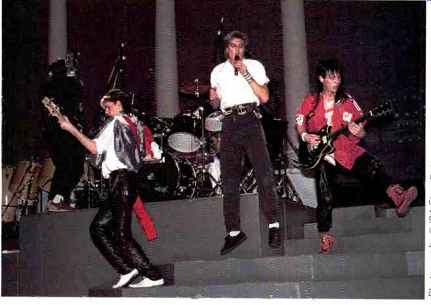

---ROB SABINO, ADRIAN BELEW, PETER GABRIEL

AND RODGERS AT SKYLINE STUDIOS, NEW YORK CITY.

Well, disco was the music that was really happening at the time. We were a bar band, basically, Bernard Edwards, Tony and I. We were just doing the Top 40. We were gigging from place to place. What the Top 40 consisted of then was rock 'n' roll tunes from Thin Lizzy and groups like that, but the bulk of the stuff was disco songs. The Trammps and The Bee Gees. This was when Saturday Night Fever was happening. Cocomotion, Donna Summer, Silver Convention, that was the stuff that was really happening. This was what was on the radio and the Top 40, so consequently this is what was in our repertoire. From doing gigs, you grew to like it. I've always liked whatever I've played. I'm not anti any type of music. I used to play in folk bands when that was happening. Bluegrass, I still like bluegrass.

I started to really enjoy playing pop music. Then I started to try and write it.

Anyway, so we had a rock 'n' roll band or a jazz fusion kind of rock band, and we weren't really getting anywhere. Everybody liked our tapes, but when they saw us, because we were basically a black band, I guess [they thought] the sound was sort of black because of our vocal sound.

When I listen to the tapes now I say this is total nonsense, how could they ever know? We didn't sound like a black band. We weren't singing like Earth, Wind and Fire, we were singing like The Stones. That's where we were coming from at that time. But anyway, we couldn't get a record deal until we did "Dance, Dance, Dance." Now meanwhile, we had been writing songs all along, but they were all rock 'n' roll songs. Power chords and the whole bit. As soon as we did "Dance, Dance, Dance," our first disco song, we got a record deal.

So that's what you meant by out of necessity-they would not accept a black band playing rock 'n' roll?

Absolutely not. They definitely would not, there's no question about it. And they loved our tapes. They used to keep them at all the record companies, but when they looked at our pictures or when they'd meet us, they'd say, "How do you market these guys? Who's their audience?" We would say, "What do you mean, how do you market us? You market us to the same people who are buying the records we buy." It just didn't make sense.

You've said and others have said that the white New Wave groups now and in the recent past are just doing disco.

Yeah, it's true. It's funny because it's actually hip now. A lot of the bands that I meet, especially those who came out of the whole New Romantic phase, they love the word disco. They think it's a cool thing. When they're sitting down writing a song they say, "I want something that's a real disco kind of record." They're into it. It's a great thing to them. I can just remember when they had the whole backlash, the Disco Sucks campaign. This is very funny.

We went to a party for Record World or Cashbox, or one of those magazines. It was in a club, a restaurant in the front and a disco in the back. Because at that time disco sucked-it was the funniest thing you could ever imagine nobody would go to the disco. They were all afraid [laughter]! We were dying. Bernard and I walked in and everybody was packed in like sardines in the front part because they were so terrified to walk into the disco. It was such a bad word. Meanwhile, the number-one record was "Funkytown." It was the funniest thing I'd ever seen in my life. I said, "Damn, these are the people in my industry. These are the hip people. These are the people who grew up with rock 'n' roll. These are the rebels. Look at them, they're fucking cowards! They're afraid to go into the disco!" Wouldn't you think this battle had already been fought in the '60s by the Motown people? This stuff about white music and black music.

No, no. It seems like it's always going to be an issue, unfortunately, or at least for a long time. You know, when I did the Bowie record, I must say David is a pretty hip guy to take a chance like that, because everybody around was saying, "Oh, that'll never happen. How can you mix somebody who's great like David Bowie with somebody like Nile who does disco records? And disco sucks, everybody! Right? I mean, it's not happening." When we sat down and talked, he realized I was into a lot more. And I don't mean to say that disco is not happening. Take it from a guy who has played everything. I mean, I used to be in blues bands for years and I know, man, when I was playing in blues bands we were looking for new ways to play changes. I loved it when somebody turned me on to a progression. Like, if we had a couple of minor seven chords in there, wow! This is happening! In fact, disco music employed much more sophisticated chord changes than any other type of pop music that I ever played before. To me, I was playing jazz, just with a cool beat, basically. You know, with good hooks.

All that's to say that when I started talking to Bowie, we started talking about other forms of music. We even started talking about opera. He realized, I guess he probably knew it beforehand, but with musicians it's just communication. You want to extract from all different styles. Stevie Ray Vaughan did all the solos on the Let's Dance album, and he's a very strong blues stylist. It worked because the different things just mesh. You use somebody's ears to talk to you through their concept. I mean, so what, was Stevie Ray Vaughan playing black music? Is he a white guy playing black music? Yeah, you can argue the roots, but there are a lot of great white guitar players who play blues, and they play fantastic. When I was a kid-and I grew up in basically a serious jazz household-I remember my uncle, who was a great arranger, always used to say to me, "Man, when I was younger I used to think that white cats couldn't play, but half the guys in my band are white guys." That's ridiculous. All the great horn players I use now are white guys, and they're all young, too. So where did they learn? I even feel stupid talking about it, actually. In my lifetime I know that that's so ridiculous. And I know that nobody-or at least I hope nobody-is hiring me because of the fact that I'm black. I know that when I call guys, I've never heard anyone say that.

The weirdest person I've ever had work on a record with me is Anton Fig, because he's from South Africa. He comes in and everybody goes, "Yo, man!" He hears all the South African jokes, poor guy. Everybody goes, "Hey, whoop, I guess this is the first time you ever played with black people, hey Anton?" I guess it's some sort of issue. We seem to be chipping away at the iceberg a little bit now. Now you see these great collaborations. I don't think anyone even thinks about it. I don't think, if somebody calls me up, that they. were sitting there talking to their manager saying, "Let's call that black guy Nile to come and produce the record." I don't say, "Hey, let's get that white guy Daryl Hall to come and sing backup."

Was that whole "death to disco" thing racial?

I don't know. Of course, I'm sure that it was some sort of weird blue-collar movement or something like that, people who were saying, "Where are The Stones?" Because those types of bands really did suffer during that period. I'm a pro now, I know what record sales were doing in that time.

A lot of these total unknown people like Silver Convention, who were they? They came out of nowhere and were topping the charts. Donna Summer and stuff, just out of nowhere. Stars were coming. I guess that happens with any new movement.

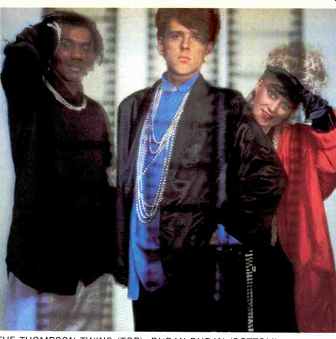

Where did groups like The Thompson Twins come from? Or Duran Duran and Culture Club? Out of nowhere. So what happened is that these new groups were coming and doing a lot better than the established bands.

During those days I couldn't even find an Elton John record, and he was my favorite. The disco stuff was really happening. Everybody was doing disco, Frank Sinatra, Dolly Parton, everybody.

Was disco music really a producer's medium?

More so than any other type of music?

Yeah.

No, no. the only thing that happened was that for the first time it was a little bit more honest .... I guess it was the techno stuff, that's what changed it around. The fact that drum machines were introduced, and sequencers and things like that. So if one person could do all the jobs, he would do it. In the old days it was very rare that you'd find somebody like Stevie Wonder or Steve Winwood. Those people were unique.

You wouldn't see albums where one guy played bass, guitar, and the whole bit. But since synthesizers came of age, one person could go play the whole thing. So when disco was popular, one or two people could do the whole thing. I guess that's where that came from.

But also, weren't a lot of these disco groups just manufactured groups that some producer put together in a recording studio?

Oh, well, come on! That's the history of rock 'n' roll! Come on! How many bands have you had where they really couldn't play? They'd leave the studio and the producer would come in at night and play the parts right. Or else the band would just look great, and they'd put them out there anyway.

You'd see them live and go, "What? That's the same group?" Come on, that's records, that's not a bad thing.

It's not an everyday practice, but how about The Monkees? They had great records. Still some of my favorite records are Monkees records. Who knows how that stuff was done? I never saw The Monkees live. The Archies.

Big novelty records were all production records.

I suppose you could say the same thing about The Sex Pistols, too.

Yeah, right. There are a lot of bands like that. A lot of groups can have weak links in the chain. Usually somebody else in the band can cover the part for a record. We all know about the famous Troggs tape. They couldn't even get the rhythm track down. I don't know if it's a joke or whatever ...

What's the famous Troggs tape?

You don't know about that?

No.

Everybody in the recording business knows about that tape. After they had "Wild Thing" these guys are supposed to be out in the studio doing their next record. They couldn't even get the rhythm track together and they broke out into a big fight. Most recording studios have this Troggs tape in their library. You put it on and you hear the guys trying to rehearse the song and they can't get it together. Finally they start having a fight and they're cursing each other out. They're going [with English accent], "Oh, you fucking asshole, you played the thing right the first time! You went do, do, do, do, do! Just do it again!" Who knows who ended up really playing the drum part? I think that's a real minor issue. That's like saying, when you look at a movie, who did what? Who knows what you do to get a movie made? Anything that's recorded, the magic should be in the recording, in the product itself. A record is different from a live performance. That's what you're buying; you're buying the record. I saw the movie Diva, and they were asking the woman who played the diva how come she'd never done a record. She says, "Because in my concept of music, music is a fleeting moment. It's only meant to be enjoyed while it's passing because tonight I may sing this and tomorrow I may sing that. It's only important while it's happening. It's not important sitting on the shelf." That was sort of cool in a way. But records are important because you want to enjoy what was captured that moment, that night, to be shared with everyone. There are a lot of things you can do with a record that you can't do on stage.

So making a record sound like the artist does on stage is not an important factor for you?

Nah. Totally not. When I first heard Hendrix's Axis: Bold as Love and I heard them do that tape flanging thing, who knows who thought of that?

All I know is that I bought a Hendrix record, and that thing went [he imitates a tape flanging sound]. Who cares who thought of that? I was listening to a record. It knocked me out. I bought a Sly Stone record the other day because I want to cover a song. This thing had this extreme stereo stuff, the whole band over here and a tambourine on the right side. I thought, "What dodo came up with this?" Obviously it was hip in those days. I thought it was the greatest thing, because basically we just wanted mono. We wanted two mono speakers.

Let's talk about electronics a little bit. You're a believer in electronics, technology, synthesizers.

Oh, to the highest order.

You never worry about losing musicality or soul in the larger sense?

Never. Absolutely never. As a matter of fact, on my album--and I play guitar--a friend of mine came in; he had some programs of guitar sounds that we put into a drum machine that I was absolutely in love with because of the sound. I didn't care that I wasn't playing the guitar. It was the sound that was great to me, and I was making a record. I came up with the ideas and concepts, and when this record comes out it's going to say Nile Rodgers. So on one song I did some guitar programming, and some bass programming. Who care about that stuff? That limits your art. It's all just paint, right? You just have to grab all the colors you can get. If somebody introduces these new metallic colors that have bits of metal flake in them and gold leaf and stuff-all of a sudden you're starting to get a texture to your work that you didn't have before when you just worked with these primary, oil-based paints with no other textures in them.

Somebody introduces a new thing and you say, "Damn, look at this great stuff I can do." Other people develop styles around materials. You can see certain artists who develop styles around just what they use. Technology just allows composers especially to be more creative than they have been. I mean, I can't play the French horn but I have some great French horn sounds in my Synclavier. It allows me to interpret the French horn the way I hear it. In the old days when I had Chic, sometimes it was damn frustrating to write out the arrangements and listen to them played poorly all day. I mean, I'd just sit there for hours and hours and hours. And I'd say to myself, "Damn, I wish I could play cello because I'd have it right." Of course, the other side of the coin is that sometimes you get an interpretation from a musician that you would have never thought of in a million years. You can write out a chart for somebody, and you're listening to the section, and somebody in the back makes a mistake and you go, "Wait a minute, what was that again?" You say, "Wait a minute, that's all wrong," and you look at the paper and the copyist copied it wrong, but it sounds hip and you use it. Of course, you lose that spontaneity.

And musicians lose jobs too, right?

Not that I know of.

I mean, if you don't need a string section, that string section is out of work.

Yeah, but hell, all my life I've always been in the .... You know I went to classical school. Hell, how many jobs did I get, you know? I never heard the concertmaster sitting around saying, "Damn, you know, we need to find some more pieces for classical guitar players. Man, I sure miss that guy who used to play in our orchestra." No way.

Hey, come on.

Are people just going to have to adapt to electronics? Is it like when sound came in to the movies? There were a lot of people squawking about how horrible it was, and it would change everything, and it would cheapen everything. And, of course, ultimately it didn't.

Well, initially it did because you had to get used to the new. You were only accustomed to the old. You were accustomed to these great mime artists, these people who could emote and make you laugh without saying a word.

So we just had to get used to the people talking. Some of them had terrible voices and we couldn't stand them any longer. A lot of them were great and they continued on.

Is that where we're at now with electronics in the record industry? I don't think so. I don't think that it is such a major issue at this point. I personally think that recorded music and live music are two different things. I, for one, when I go see bands nowadays and I see them playing tapes and things like that-I don't come from that school-to me that's the funniest thing I've ever seen in my life.

You mean like Frankie Goes to Hollywood?

Sure. There's a million of them. Big ones. Good ones. I'm sitting there going, "What is this?" I see the drummer go and flick on the tape of a bass drum going boom, boom, boom. That's totally ridiculous to me. I didn't study all these years to go play a tape when I'm doing a live show.

So that's jive?

To me it is. I believe in playing. But to me a record is a record. The thing that makes me fascinated with records and films is, I'm blown away with technology. I don't want to see a film that's washed-out black and white like the old days, and subtitles on the screen and no talking. I want to see more and more technology. When they improve the sound in the theater to sound like the sound in my home, then I'll even love it more. I like new things. I want to see more innovation. And personally, as a composer and as a writer, I like the freedom of being able to do my own horn parts myself on a synthesizer, and use my interpretation and know that the damn thing is going to be right when I get finished playing with it. I think that's a great thing.

What's the cutting edge right now in technology, and what are the things we can look for in the next few years?

Right now it's fascinating to me. This is the most stimulated I've ever been in my whole life. I can't even keep up with all this junk I'm buying. To me the most fascinating thing, and I know to some people this is going to sound like a drag .... We're working on systems where if somebody who lives in England, say, has a system similar to what I have, and he's got a track and he wants me to play on it, well, he can send it to me over the satellite to New York. My system can pick it up. It will go down on tape. I can listen to it, put my guitar overdub on it, send it back to him, and it'll all be digital information. It will sound exactly the same as when I played it. And it'll be clear as a bell and it'll be dynamite. Right there in his home as if I were there playing it with him. We just transfer the messages to each other digitally. The quality is perfect. Now, a lot of people would argue about that, but to me that's great, that's efficient. Now I don't have to go there and move into a hotel, and raise the budget $20,000 or even hassle with England! I think that's a great thing. In fact, that's more communication, not less. I can play on your record if you're anywhere.

It sounds like the music industry's "global village." Yeah. It's all just communication.

Is that system something that is really imminent?

Absolutely. Maybe in the next year or two. Oh, yeah, it's going to be happening in a big way.

How did you make the move from being a performer and producing your own records to producing other people's records? To be totally honest, Chic was only a production to us. Chic was not the band that we were going to be in. It was like what you were talking about before, disco being a producer's thing.

Well, yeah, we were producers, we were songwriters. We also sang and performed, but we didn't feel that we had to go out and represent it. Quite frankly, we didn't know if it would be a hit or not, because we had so many bad things happen to us, plus we really wanted to be rock stars. We didn't see ourselves just playing in clubs. We wanted to be like, all right! [He mimics the sounds of a huge crowd, and laughs.] That sort of thing. We didn't basically want to assume responsibility for Chic. We didn't really know what this disco thing was all about. We were just writing songs that sounded good to us, that made us feel great, that made us want to dance to them.

But right from the beginning you produced the group yourself with Bernard Edwards. There was never any question of bringing in an outside producer.

We were Chic. But the thing is, we weren't necessarily going to be Chic forever.

How did you also decide you wanted to be a production whiz for other recording artists? That was purely an accident. Other producers were producing us before we were Chic officially. And no one could get a record from us because we were over players. We wanted to be players! We were musicians. Jazz, man! So when a producer came in he could never communicate with us and make us understand that we were making records. Now, this was us; we didn't want to be seen as The Monkees, we wanted to be like Return to Forever, that's where we were coming from. No producers could get records on us. They got records, but they were like son of Mahavishnu.

These were records that never actually came out? Absolutely never came out. They were tapes; they never actually became records. No record company signed us.

We decided to cut our own stuff. It started off as jazz, then progressively became more commercial. The first proper disco record we wrote-it's funny to say proper disco record-was "Everybody Dance," which was the most jazz-like song in our repertoire.

When we realized that, we did it for ourselves-we did this not as a musical representation of ourselves, but as what we could do if we wanted to make a commercial record. We thought we could .. .... produce this product.

Right. When you're actually there doing it, you think it's something special, and something really heavy. So once we did it for ourselves we said, "Damn, we could probably do this with anybody." That's really how cocky we were. This was our first record, and we went to the head of Atlantic Records and said, "You know, we could make your secretary a star." This is really funny [laughter]. We were 20-something years old and we're in there telling the president of Atlantic Records that we could make his secretary a star because we thought that we had really lucked onto something. Not realizing that all we had found was songs, and people who could play the tracks, and people-us-who could make them into records. But we didn't know that.

We thought we had done something magical. We didn't realize that all we were was just producers, and we just happened to be songwriters and musicians as well, and also I did the arrangements.

So when did you figure that out? It took a while, because we had all these big records. And we didn't realize that all we were doing was what people like Quincy Jones or Phil Ramone do. I don't really know how they produce records because I've led a very sheltered life. I've never really worked with other producers outside of Bernard Edwards.

Did it take a stumble or two on your part?

Yeah, it took working with Diana Ross on Diana. That's when we realized that we didn't understand why things were going so well for ourselves. We had no idea. We said, "Damn, what did we do? We wrote a song. We cut a track.

We went in there and sang it." We didn't think we were the greatest singers in the world, so why did that work? Because it just did.

---HALL AND OATES

So what happened with Diana?

See, we had never worked with stars before. We didn't realize that there was a communication thing. We didn't realize what producers did. We thought that whenever we produced a record all we did was sit at home and write all NA m u these songs. Once the songs are written, we go in and cut the tracks. Once the tracks are cut, we go in and put the backgrounds on. Then we sing the lead vocals. That's how we produced a record. So it was no different for anyone. Sister Sledge, Diana Ross, we didn't care who it was. Diana Ross walks into the studio and says, "Well, how do the songs go?" We said, "What do you mean, how do the songs go? We're going to go home and write them. We don't know how they go.

What do you want the songs to be about?" "Well, my life is here in New York and I don't want any of the old life.

I don't want to talk anything about California or my past relationships." I said, "Great, so you're coming out with a new bag." We wrote that down and went home and wrote "I'm Coming Out." That's how it worked to us. That's it. That's how you produce a record. So Diana said, "I'm going to have to hear the songs." We said, "Sure, you'll hear them when it's time to sing them." We had no idea. We thought everybody did it that way. We really did. So then we got pissed off. We said, "What do you mean? You mean you have to hear the songs? Oh, so we're auditioning for you? What do you mean by that?" She says, "Well, I've never just walked into the studio and somebody tells me to sing, 'I'm coming out, I want the world to see.' " We said, "All these big records you've had, what do you mean you've never done that?" We honestly didn't know. We never rehearsed. Rehearsal? I'd never heard of such a thing. "Oh, we got to learn the songs first and then record them?" I said, "I'm a pro, you can teach the song to me in the studio and I'll play it." I mean, I survived like that at the Apollo. You learned the show that morning and you had to play it that afternoon.

But that's not the way records are made, you found out.

But I didn't know that. We had a big fight with Diana Ross. She left the studio and we didn't see her for months.

Really? Over this .. . Over just the way that we worked. This whole thing of, "Well, you come in and we'll tell you what to sing, and when you finish singing it we'll tell you when you can go home." And we're, like, 25 years old, and this is Diana Ross! Well, we truly didn't know. I mean, we

weren't trying to be crazy or tough, we honestly didn't know any other way. If somebody had proposed a different sort of way to us, we couldn't guarantee that the record would sound right.

Because I didn't know how to do it if it wasn't my song. I couldn't imagine what the record would sound like.

She actually remixed the record herself without your approval, didn't she? Absolutely.

And that's the way it came out?

Shee, boy, did it ever. But, you know, what happened is that a really great friend of ours, Bob Clearmountain [an engineer and producer], listened to her version of it and said, "You know, Nile, these are great songs, man. You can't keep a record like this down. No matter how bad this sounds to you, believe me, to the people it's going to sound dynamite." I said, "Bob, listen to it, there's no bass, there's no nothing.

My guitar doesn't sound like that.

That's the worst guitar sound I've ever heard in my life!" [Laughter.] He said, " Nile, trust me, man. It's cool. That's how Motown records sound. It's cool." He was right. I really was afraid. I was terrified. I thought the record was going to be a huge flop, just because of the sound. It shows how paranoid you can get about something like that when really, like people say, "If it's in the grooves, it's in the grooves." It's hard to mess it up.

You still don't like it, huh? No, well, I have the original at home so it sounds great to me! You play the original? Of course. Of course! I have the real one, with the real big horn sound. Oh, they made a mistake because they didn't know that was going on, they didn't know how we did the record. We built a composite trombone solo which is fantastic on my record. On their record . the guy made a lot of mistakes-which wound up being cool, ultimately, in the end, because they're good players. He didn't make a total jerk out of himself. But on mine he's really wailing. He sounds fantastic.

We'll never know. When should an artist produce himself, and when should he go to an outside producer? That's a very difficult question to answer. But let me say this to you as an artist finishing my own record: It makes you incredibly anxious. I don't know if I'm as objective as I'd like to be, even though it's a very subjective medium. I don't know if I can say, sometimes, if I want to go with this thing because it's best for the record or because I want to appear hip. Do you know what I mean? I might want to take this lyric out because I feel stupid talking about, say, Kellogg's corn flakes, so I put in sushi instead to sound hip ... Even though Kellogg's corn flakes might be better for the disc? Right. Whereas if it were your song I'd say to you, "Come on, give me a break. Kellogg's corn flakes is happening, everybody knows about that. So what if your snooty, cool New York friends know about sushi, big deal!" That's the difficult part because when you're producing yourself, you're like an actor. Now that I've been working with films and stuff I see how actors are very conscious about how they're coming off. So they're looking for scripts and saying, "Damn, when so-and-so says that line he really comes off heavy, that sounds dynamite." And they go to the director and say, "Can I have that line?" You start doing that to yourself. You say, "Wow, when so-andso gets that part it sounds really cool; maybe if I put that on a guitar, I'll have a cool part." It may sound really petty, but I'm sure a lot of people get into that sort of thing. Because you are talking about yourself, and you're molding yourself to the way people are going to see you.

Do you think there are a lot of people who are producing themselves who shouldn't be? Yes. But then there are also a lot of people who produce themselves who do great work. Also, some of the people who I think are great artists allow themselves to be produced well. Certain people are just fabulous artists, and whoever they're being produced by, they'll always shine through. The artistry is always there. Bowie is like that. David Bowie will never not be Bowie. He'll always be Bowie, there's no way you can change that. Or somebody like Jagger. Oh, even a better example is Madonna. She'll always be Madonna, no matter what. She is one of those really special, unique artists that .... I swear, I wish a lot of producers could work with people like that.

She's the kind of person you dream about. The kind of person you know will work on it until it's right. And what's right for Madonna is the same kind of thing that's right for Bowie-the question is whether the feeling is right, not whether they sang it perfectly. If the story is being told properly. When you hear their records you know just what they're talking about.

Does a Madonna or Bowie know what they want when they come into a studio, or are they just very receptive to a good producer?

I think they have a very good idea of what they want, and they're also very receptive. What governs this stuff? What's wrong? What's right? Who knows what can change it from day to day? I can wake up in the morning with a very clear picture of how a song is going to be, and I get to the studio and it just doesn't work. You don't like it, even though you were clear on it. It's just not happening. So if somebody suggests a better way to do it, sure, you can fight it and just insist that your way is happening because you wrote it. Or else you go along with it and try and develop it with him. It's having very strong editing powers-that's what I think a good producer is, a person who can take their ideas and stop them, like that, in an instant, and let their minds be free and listen totally to what somebody's got to say. Something new. That's what makes a person a good, receptive artist or producer.

That you can stop your idea and totally grasp what another person is saying and either develop it with him or make the decision right on the spot, "Nope, it's not happening, let's move on to another idea." That's my payoff in this business. What I get out of the record is the enjoyment of those moments when that happens. And it happens every day, 20 or 30 times a day. To be able to stop and create something out of just a shell of something that was there.

And you have that power to say, "Nope, it's not happening," even with a Bowie or a Jagger?

Yes. I think that's my greatest asset or my greatest value to a person, the fact that I'm a songwriter. I write melodies all day. So if you come in and you have a song, and you say there's some part that just doesn't make sense to you, I can give you a thousand suggestions, I hope. Some days I can't, but those are the days we just go home early.

That happens from time to time? Oh, man, it happens all the time.

Do you consider yourself a good technician on the board in a studio? Oh, no. Heavens no. I mean, I know how it works, and I can work a board if I have to. But I'm not an engineer/ producer. I didn't go to engineering school. This would be Greek to me except that I've been doing it so long that I know what it all does now. Plus, I have a little studio at home, and they're all the same. I truly believe in great engineers. That's the thing to me. Dig this, I'm really simple when it comes to music. I think that first you have a song. Then everybody connected with that song has to make the song better, no matter who it is, whether it's the assistant engineer, the singer, the bass player, the guitar player, everybody's got to make it better than what you did at home by yourself. If I come in and think I have a good song, rehearsing with my band, when I come in and play it you got to make it better than what I just did. / can make it as good as I made the demo at home.

Anybody can do that.

Let's talk about some of the people you've worked with as a producer.

Let's start with Jagger. You did three cuts on his solo record. How did that come about, and was he a little nervous about making his first solo?

Outwardly, no. Inwardly I'm sure he probably was nervous. If he says he wasn't, then I like him even more than I like him. I think he's great.

How could you be in The Rolling Stones and be Mick Jagger and not be nervous about making a solo record?

Damn, if he isn't nervous then he's really hip [laughter]. I'm nervous! Were you nervous working with him? No. I'm never, never nervous working with people. No, I mean I was nervous making my own solo record, so I know Jagger had to be nervous.

Did the songs come together relatively easily?

Well, you know, we had a feeling-out period of him starting to understand my sounds, and me understanding his sounds, and his technique and my technique. Finally, talking worked everything out. When Mick Jagger said, " Nile, get the hell out of the studio and get in the control room," I said, "Now I know what you want!" [Laughter.] Then I understood. I said, "Right, Mick. Gotcha, pal!" And then I really dug it. As soon as he said that to me it was very clear. But for two weeks it was like boxers trying to feel out .... got that punch in. Great. Well here's a couple more. After that we were cool. I realized he wanted a producer-producer. He wanted me in there working on sounds. He wanted me to capture the moments, these fleeting bits that would go by and he'd say, "Whoops, that's it-hold on to that thing." I couldn't do it if I'm out in the studio jamming, because my music is fleeting too. And I'm hanging out with all the guys, and we were losing stuff. That's the way he makes records, whereas I make my decisions right on the spot.

On every record that I do there's only one copy. I don't have two versions of anything. Either it's happening or it's not. With Mick, he's from a different school, sort of like Bryan Ferry. They want you to play everything possible and then they'll figure out which parts are hip, and then ask you to refine that.

Are you going to be doing the new Stones record? No. We were talking about this for a long time. I guess I can't say no, because I don't really know what stage they're in. He's in town now so I guess I'll ring him and see what the deal is. I would think it's probably good for them to try and do it by themselves. It seems to be working out.

But you'd like to do it, obviously.

Of course. Who wouldn't want to do The Stones?

Do you like being a session musician? I know, for instance, you played guitar for Bryan Ferry.

I love being a session person. I have a philosophy about that too: I don't learn my own songs and I don't learn your songs, either. I don't rehearse. You give me the chart when I get to the studio. Either you give me the chart or I'll learn it with the band or whatever. I play my best guitar on your record.

Let's go on to some others you've produced. Jeff Beck-was he a hero of yours as a guitar player? Serious hero. Jeff, he's the man to me.

He's the greatest guitar player alive today, in my opinion. He plays what I would like to hear more than any other guitar player. When I worked with Jeff I had a different concept in mind. I wanted to make a record with somebody like that very accessible. I want other people to enjoy Jeff Beck's guitar playing as much as I do, and the way to get that out there is to have him on a song.

Not just great fusion records, which I'm sure he can do forever without me. I wanted to give him songs that people would sing. So that's what I tried to do.

I tried .to say to him, "Like 'Beat It.' " The reason why Eddie Van Halen's solo is so great on "Beat It" is not just because it's great-it is, and he plays great solos all the time-but because of the fact that it's on that cool song! That's what makes it really happening.

Was Beck there for that? Did he understand that? Oh yeah, sure. We talked about it a lot.

He likes my songs. We had a good time.

That's not a problem for someone who came out of the '60s, the long-guitar solo era? Well, I let him play long guitar solos

[laughter].

How about Duran Duran?

Duran Duran is not quite the same as these other people. First of all they're a group. It's a completely different relationship than with a 'solo artist. When you're dealing with a group it's almost like first you have to be the den mother, like a Boy Scout troop. You have to gain the respect of everyone, which is cool. I don't have any problem with that. Duran Duran were fans of mine before I worked with them. They loved Chic music, so that was great. Plus, there were a lot of Duran Duran songs that I liked as well. Bands are a very different animal. You have to deal with the personalities collectively and individually. And I work best on a one-toone basis. I just grew up working with individuals. There's a lot of psychology that goes into production because these people are stars and you absolutely have to respect that. I always feel that I work for you, not that you work for me. I don't even feel like I work with you. I'm employed by you. And I think that it's your record, and you got to give a person that. So when it's five people and you have to give them their records individually and collectively, it's rough. But I get along great with Duran Duran.

Do they make records as great as their videos?

They make great videos. They make good records too. I mean, some of their songs I like more than others, but that's true of any artist. I guess Duran Duran probably falls under more criticism because of the audience they appeal to. If they appealed to older people like Bryan Ferry does, I guess they'd be really hip. Their songs are cool. Like "Don't Say a Prayer." When I saw them live I was crying when they did that song. I was standing on the side and I heard this [he mimics the rhythm] and it sounded so beautiful to me the tears started streaming down my face. Madonna looked at me and went, "Yo, brother, where're you coming from?"

And Madonna?

Madonna is the greatest, I don't care what anyone says. Madonna is so cool.

I said this to Diana Ross, too. I said, "I wish everybody were like Madonna, in a weird way." I like the fact that she's the hardest working person I've ever seen in my life. She was here in the studio before me most of the time.

She'd swim like miles every day before she came to sing. That kind of dedication I don't see too often. It makes you feel proud. It makes you feel dedicated. It makes me say, "Hmm, maybe I'm getting a little fat here around the middle. Maybe I should go practice."

Is she a great singer? Does she really care about being a great singer?

I don't know if she cares about being a great singer. I think she cares about being a good singer and being a good storyteller, and that's what singing is about to me. That's all that it's about. I mean, is Bowie a great singer? What's a great singer? I mean, yeah, Aretha's a great singer. But Bowie is a great songster. He tells the story and he means it. He delivers the story. To me, I'd rather work with somebody like that than a great singer, because I make records. I'm not really capturing what I consider in my head great live performances. I'm making a contrived thing for a specific type of artistic statement-a record. So even if you sang the same part five times, who cares? If the fifth one is right, that's the one that goes on the record, not the first one.

Because this is captured forever. You want it to be dynamite.

----THE THOMPSON TWINS (TOP); DURAN DURAN (ABOVE).

(Source: Audio magazine, Sept. 1985,)

= = = =