s

s

by Edward Tatnall Canby

--------A Tribute to Charlie Chaplin. London Festival Orch. and Chorus, Black. London Phase 4 SP 44184, stereo, $ 5.98.

Charlie Chaplin, the visible film star, continues to make such an immediate and lasting impact on us that C. Chaplin, composer of virtually all the music you ever hear with the Chaplin films (not counting the silent ones with local pianist in the house) is scarcely ever noticed. He's there, the whole time.

The Chaplin music is decidedly film stuff and no two ways about that, as you'll find when you play this record.

Old fashioned? Of course-much of it dates from the early sound-picture era. But the newer music is pretty much indistinguishable. Content? Well, how can one put it? The Chaplin style is skillfully omnivorous, a bit of everything (except modern), to suit every (film) occasion. The writing is slick and expert-assuming that Charlie isn't ghosted by a host of able assistants. The content is memorable in a certain extremely limited sense: Yes, you will hum the tunes now and then. They catch. Other than that, it all slips in and out of the ears, leaving scarcely a trace, just a mood. That was the idea.

You will pardon me if I suggest that since Charlie's producing heydays our film music has considerably widened and deepened. The norm is now far more modern. Electronic music, dissonance, far-out "classical" (like the "Elvira Madigan" Mozart piano concerto), all have their place in our film consciousness. Film music still has the same end, as a vital but secondary element in the total presentation. But our film-music language has expanded. It can say and do more these days.

Yet the barrage of `oldie" films forever on TV and in the theaters keeps the earlier and more conventional musical styles alive in our ears, concurrently with the new ways. We can "read" both. Thus Charlie's music fits right into the TV background-and no matter when he composed the notes, early or late. Whether you'll want to listen to straight Chaplin, minus foreground, is a question, unless it brings back the scenes for you.

It probably won't do that because, if I am right, a lot of this music has yet to be heard around town. "A King in New York," for instance, or "A Countess from Hong Kong," plus something called "Chaplin Revue." The rest is from the big old talkies and semi-talkies, "Modern Times," "Dictator," "City Lights." Oh yes--and a few items are by somebody else, though from Chaplin films. L. Daniderff, J. Padilla. You won't really know the diff.

Performances: OK, Sound: B

Franz Liszt's Greatest Hits of the 1850's. Jorge Bolet, piano. RCA LSC 3259, stereo, $ 5.98.

"Transcriptions," they called these--we'd be more likely to call them freely composed Fantasies; for they do not in any way tend towards faithfulness to the Original! That idea didn't arrive for a hundred years. Instead, old Liszt, the super-showman pianist (who could be heard only in the concert hall, or in some very exclusive social salon, or in his own studio) took then-familiar airs, arias, hunks of heavyweight opera, and re-composed his own special version of the music, in the Liszt style. Of course! Why not? Liszt was the guy who played them after all. They were vehicles for his public spectacles and they had to sound like him.

So we have Donizetti, Schubert, Verdi, Wagner, Chopin, Schumann, a galaxy of different talents, all sugared up into the expert Liszt confection, ultra-musical always, covered with glittering masses of pianistic ice, incredibly difficult to perform and sounding easy-that is, when played the way Liszt undoubtedly played them. Some pianists fail miserably. All you can hear is the glitter and the icing. The music gets lost in the finger-work.

Not here. Jorge Bolet has a big rep for Liszt playing and rightly so. His style is a bit dry and pointed in the finger ends, perhaps not as smoochy as Liszt himself could well have been, back around 1850. But no matter-for the musical sense gets through in all senses. Melody, harmony, the style and intent of the original composer, even the imaginative rendering of the original "instrumentation," everything from a solo aria or solo piano piece to a vast opera chorus with big orchestra.

Performance: A, Sound: B +

Monteverdi: II Ritorno D'Ulisse in Patria (1640). Concentus Musicus Wien, Harnoncourt. Telefunken "Das Alte Werk" SKB-T-23 (4 discs), stereo, $23.92.

This is one of those superb evening long album--experiences that requires as much from you, the absorbed listener, as you do from the recording. You get your money's worth, if only in sheer quantity of material presented, via the sound itself, via the vast booklet with background essays, text, and so on. I found the seldom-heard Monteverdi opera a great experience but it isn't easy. No set pieces, no arias, no symphonic interludes just, deliberately, a steady flow of half-spoken musical recitative, the entire sense of the music concentrated in the actual vocal expression of the various solo voices. A marvelously reconstructed contemporary-style accompaniment, however, adds greatly to variety and interest.

Only the early Monteverdi opera Orfeo has precise and detailed instructions as to performance. This later opera and Poppea (better known) have come down in sketch-like copies, scarcely more than the vocal line and words plus bass. Not even the later conventional figures are there-so even the harmonies are no more than implied by the bass and must be guessed from the musical context. But the biggest question is whether the sketch indicates a "chamber" style with the simplest of accompaniments or was simply a conductor's boiling-down for convenience, like a piano score of a symphony. Who knows? Maybe there was a large orchestra of contemporary instruments? Scoring was still in this period left to local imagination and seldom indicated on the written-out music.

This vast and absorbing musicological solution to the problem of performance has the typical quality of the Viennese Consentus Musicus group--incredibly careful musicology plus utterly musical performance, never for a moment dry or stodgy. The realization, with a wealth of carefully utilized instruments of Monteverdi's own time, has a Germanic thoroughness and believability. The actual performance has an Italian intensity, though the cast is international, from Sweden to England to Germany or Austria. The booklet tells all in English, German and French, the individual instruments are described in detail with pictures, the complete text is set out in parallel columns in four languages and there is even a stereo diagram so you can locate the trombones, piffari, lute, chitarrone, regal, recorders, harp, strings and so on. So-go to it!

Performance: A, Sound: B +

Adolph Busch, violin; Rudoph Serkin, Piano. Perennial Records 2006, mono, P.O. Box 437, New York 10023.

Perennial does a fine job of reviving famed old recordings not likely to reappear on major labels but they must be getting hysterical; this one has labels reversed and no notes included. (Usually, if I am right, they do a fancy job of documentation and evaluation.) We older musicians were brought up on the music of Adolph Busch and his son-in-law Rudoph Serkin, both in concerts and on disc-but that was in the last days of Busch, when his violin had become somewhat raucous and inaccurate in tone, though ever full of intensity and enthusiasm; Busch had then expanded his activities into conducting his own orchestral ensemble.

The recordings refashioned on this LP date are older; the earliest a brief acoustic Bach disc of 1924, the others from 1930 and 1931. Busch is younger, his tone clean, the notes accurate-quite another player from the familiar rough edged Busch of those somewhat later years. As for Serkin, he is of course still very much with us, if occasionally now confused with his own son, Peter Serkin.

In these recordings he furnishes an expert old-fashioned accompaniment on the piano for works that now would be heard on the harpsichord--Bach, Geminiani, Vivaldi. Also a movement of Reger, always a Serkin favorite. An addition is a Schubert song, Sei mir gegrüsst, with Heinrich Rehkemper, baritone, and Manfred Gurlitt, piano.

Performances: A, Sound: C +

(Audio magazine, 1972; Edward Tatnall Canby)

===========

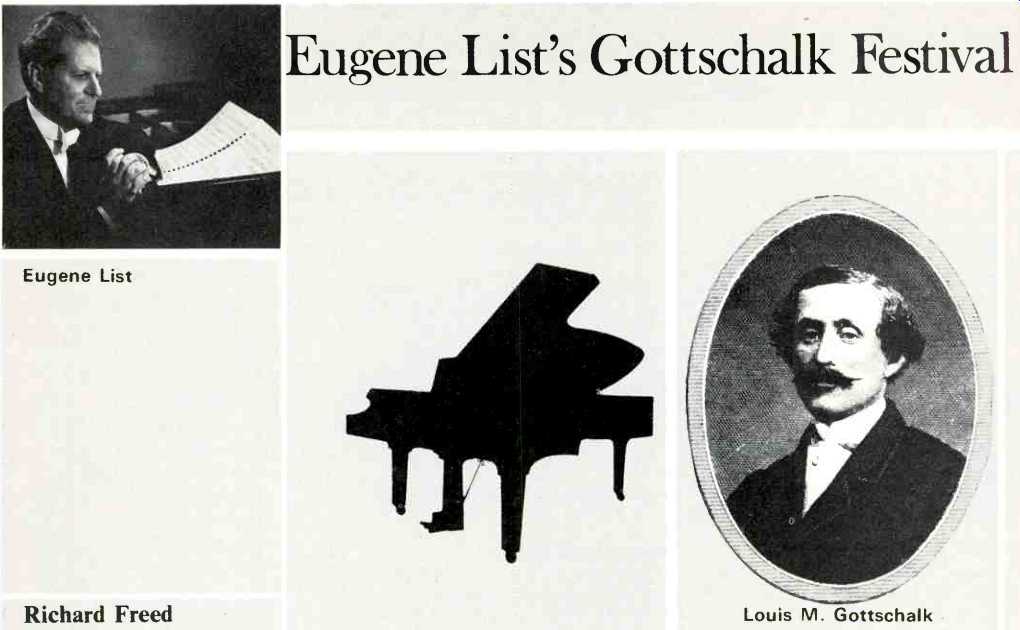

Eugene List's Gottschalk Festival

Eugene List; Louis M. Gottschalk

by Richard Freed

THE MIDDLE of the nineteenth century was the heyday of the piano virtuoso-composer, that species of showman who thrilled and amazed audiences with his keyboard Prowess, traditionally made the ladies swoon, and composed much (in many cases most) of his own material. Chopin lived into this period, but died in 1849.

Among the Titans who survived him were Franz Liszt, Sigismond Thalberg, Henri Herz, Anton Rubinstein, and the American Louis Moreau Gottschalk, to whom Chopin himself had said "I predict that you will become the king of pianists." Gottschalk, who was indeed so proclaimed on the occasion of his American debut in 1853 and many times thereafter, was 20 when Chopin died. He was born in New Orleans in 1829 and at 13 was sent to Paris for musical training. He was not accepted at the Conservatoire, whose director held that Americans were barbarians who made locomotives, not music, but within three years he received Chopin's accolade at a private performance, and four years after that his formal debut was hailed as a triumph by Victor Hugo and Théophile Gautier as well as his fellow musicians. What electrified the Parisians was not only Gottschalk's playing but his compositions, especially his Louisiana dances based on Negro and Creole music remembered from home. He had been composing piano pieces since he was 15, and many of them had already circulated by the time he first played in public; one of them, in fact, 'Bamboula, had been made a test piece for pianists at the very Conservatoire to which its composer had been denied admission, and the young "pianiste compositeur louisianais" sat on the jury with the director who had barred him.

In Paris Gottschalk had a fascinating circle of friends-Bizet, Saint-Saëns, Offenbach, Meyerbeer, Berlioz. He was admired by Liszt and Rossini, and actually assisted Berlioz in producing some of his mammoth concerts. The association with Berlioz undoubtedly gave him the idea for the "festivals" he was later to stage himself in the Caribbean and South America, actually monster concerts for which he composed his own orchestral and operatic works calling for hundreds of performers.

After the Paris debut, Gottschalk toured in Switzerland and Italy and spent a year-and-a-half at the Spanish court, where he was given lavish honors by the queen, before returning to America at the age of twenty-four. In New York, Boston and Philadelphia, he was no less an "exotic" than he had been in Europe, for his Louisiana dances were as new to those cities as to Paris and Geneva. He had brought with him a number of works reflecting his exposure to Spanish music, and he now spoke with a pronounced French accent; he lost no time, though, in beginning to compose pieces in which he quoted American national and patriotic airs, much as Charles Ives was to do a half century later. When he toured the Caribbean he absorbed new influences that were to bring forth some of his most colorful and distinctive compositions: Latin and Afro-Cuban rhythms which had not been exported before.

The flair, the bearing, and even the compound romantic involvements that went with the classic image of the virtuoso-composer were attributes Gottschalk had in abundance (in the romance department, we note that he was literally carried off the stage and abducted by an Amazonian admirer at the end of a recital in Geneva, and that his open affair in New York with the actress writer Ada Clare, who bore him a son, was chronicled by the lady herself in her newspaper column and a novel), but he also enhanced the image with his musicianship and his genuine uniqueness.

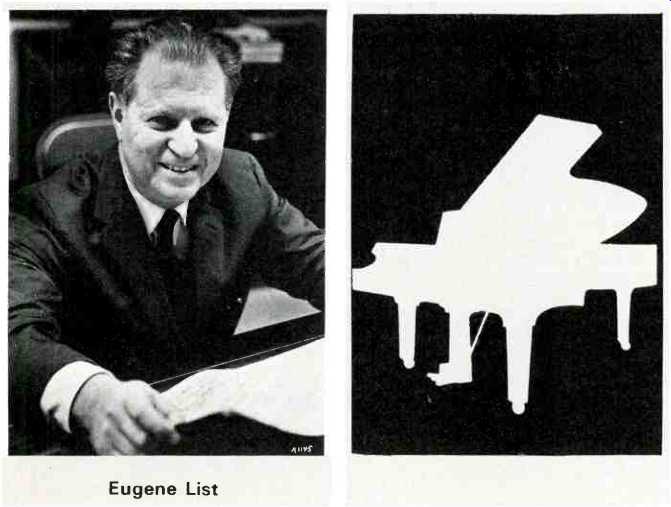

------------ Eugene List

---------------Eugene List with President Nixon and Emperor Haile Selassie at the White House during a State Dinner and Musicale in honor of Selassie.

Few of the virtuosi were significant as composers. Liszt, of course, was a great composer, and not only for the piano, but the music of Thalberg and Herz is not heard today and they are remembered, in that category, only as concocters of display-pieces for their own use. Gottschalk was not a great composer, but he was nevertheless America's first great musician. He was an original, an unpretentious but significant innovator whose influence on succeeding generations has only recently begun to be recognized.

He also happened to be an exceptionally keen and compassionate observer of humanity. From the beginning of his five-year sojourn in the West Indies, early in 1857, until December 1868, just a year before his death, Gottschalk kept a remarkable journal, subsequently published in book form as Notes of a Pianist. It is one of the most valuable of musical diaries, not only for its autobiographical material (there are no references to his amatory adventures, an omission which may be taken as an indication that Gottschalk was a true gentleman-and that he intended his journal to be published), but even more for the insightful observations on the mores and personalities of the time, and most especially for those on America during the Civil War.

Like the other virtuosi, Gottschalk composed for his own purposes as a musical showman; he never took himself too seriously as a composer, but his music has enough substance to continue delighting the ear long after it has served to display his own powers as a performer. He wrote more than piano music, too: among his works were some grandiose affairs for orchestra, some works for piano and orchestra and at least three operas as well as several multi-piano stunt pieces involving as many as 30 pianists. While it would be a gross exaggeration to compare Gottschalk with Liszt, it might not be at all unreasonable to regard him as the closest we had to an American Glinka, paving the way for Ives, one might say, as Glinka did for Mussorgsky. Tchaikovsky once said that all Russian music had grown from Glinka's Kamarinskaya as an oak from an acorn, and one might almost make similar claims for such Gottschalk works as The Banjo, Bamboula, and The Union as having borne the seeds of what made American music American-including anticipations of ragtime and jazz.

If Glinka, the father of Russian music, profited from his trip to Spain, so did Gottschalk, who wrote operas on Spanish and Portuguese themes and even made use of some of the same tunes used by Glinka in his two "Spanish overtures," most notably the celebrated Jota aragonesa (also used by Liszt in his Spanish Rhapsody), which turned up in Gottschalk's "grand symphony" for 10 pianos, The Siege of Saragossa. But Gottschalk drew really astonishing riches from his last years in the Caribbean and Latin America. He was, in fact, our first conspicuously successful ambassador of good will between the Americas. It was entirely fitting that the speaker at his funeral in Rio de Janeiro, where he died on December 18, 1869, saluted Gottschalk as the man who had "linked with his name the two continents," for he had, on his own, provided "cultural exchange" in both directions (and, indeed, in more than two). It might be in order to outline his inter-American peregrinations before proceeding to more specific matters.

After his return from Europe in 1853, Gottschalk made a brief visit to Cuba the following year, continued to perform in the United States, and then returned to the Caribbean in 1857 for a two-year concert tour with the soprano Adelina Patti, who was then only 14. When the tour ended Patti and her father returned to New York, but Gottschalk chose to remain in the islands for another three years, soaking up local color and producing the first in his series of "festival" extravaganzas. It was during this period that he wrote his Cuban dances for piano duet, his one-act opera Escenas Campestres ("Cuban Country Scenes," for a cast of three unnamed characters), and his First Symphony (Night in the Tropics, for large orchestra, full band and Afro-Cuban percussion instruments), the finale of which is nothing less than a grand samba, surely the first one in a symphonic setting.

In 1862 Gottschalk took the oath of allegiance to the Union at the American Consulate in Havana and sailed back to New York. For the next three years he toured the Union, and his programs emphasized patriotic fantasies, his biggest success being one called The Union. He played that work at a Washington recital attended by Lincoln, an event recorded in Notes of a Pianist with a poignant and frequently quoted description of the President. A few months later Gottschalk played The Union again as part of a memorial service for Lincoln, when news of the assassination was received aboard the ship carrying him to California. From California he proceeded in 1865 to Mexico, Panama, and South America, where he spent the last four years of his life.

Wherever he traveled, this "king of pianists" was received with the honors usually reserved for royalty and with a good deal more enthusiasm. A merchant in Guadeloupe had all the partitions in his house torn out to provide Gottschalk with a concert hall. The Emperor of Brazil welcomed him in 1869 by immediately placing all of his country's musical resources at his disposal, and Gottschalk used many of them in his last "monster concert," less than a month before his death. The program, which involved 650 performers, included a specially composed Marche solennelle on Brazilian themes for orchestra and brass bands, with offstage cannon in the triumphant coda. During the previous year he had composed his Second Symphony, Montevideo, in which he combined patriotic tunes from both Uruguay and the United States. The musical cross-pollination he effected between the United States, Europe, and other lands of the Western Hemisphere was to prove productive on a scale Gottschalk himself could not have dreamed of. Whether or not his music actually served as a model, he clearly anticipated styles and devices used later by such diverse creators as Ives, Mac Dowell, Milhaud, and Copland.

When Gottschalk died there was wrangling between his relatives in the States and his associates in Brazil over who was authorized to take his scores, and apparently all of his orchestral works and operas were lost at that time.

In any event, none of them was available for performance again until the last few years. Hershy Kay's marvelously sympathetic orchestration of several of the piano pieces for the ballet Cakewalk became a popular item, both with and without the stage action, more than 20 years ago, but it was not until 1955, when Howard Shanet conducted the Symphony Night in the Tropics (in reduced orchestration) at Columbia University, that any of Gottschalk's own orchestral music was heard in the United States.

There were more North American premieres as recently as 1969, in observance of the centenary of Gotts chalk's death, and still more rediscoveries were given their first performances in more than 100 years at recording sessions during December 1970 in Berlin. The recordings were released just a year ago in a three-disc Turnabout set called "A Gottschalk Festival"

Works known under more than a single title are meticulously cross-referenced.

A limited number of copies of the Offergeld catalogue were distributed free, and now there are no more. This is a document which simply must be kept available. (The numbers assigned to the respective works by Offergeld are used, by the way, in the annotation and label copy for the Turnabout album.) Harold C. Schonberg, music critic of The New York Times, has been an enthusiastic drum-beater for the Gottschalk cause. He has written several articles about Gottschalk, mentioned him prominently in his book The Great Pianists (Simon and Schuster), and he betook himself to New Orleans in February 1969 to cover the anniversary concert in which Werner Torkanowsky conducted the New Orleans Philharmonic in the North American premieres of Montevideo, the Marcha triunfal, Escenas Campestres, and the original piano-and-orchestra version of the Portuguese Variations. Eugene List was the soloist in the Variations, and also in the Grande Tarantelle, and, as already mentioned, it was he who made all these works available for performance.

List's first major encounter with Gottschalk came in the mid-Fifties, when he made his celebrated recording of a dozen solo pieces for Vanguard (VRS-485, now a collector's item). He was intrigued by the Gottschalk lore he acquired from Vanguard's famous staff musicologist Sidney Finkelstein, and it occurred to him that any pianist composer with Gottschalk's flair must have written works for piano with orchestra; he determined to look for them, and first armed himself with a well-worn copy of the 1881 edition of Notes of a Pianist (the Behrend edition was then still eight or nine years in the future), which he all but memorized.

His first big catch was the Grande Tarantelle.

After trying various sources in Brazil and Paris, List succeeded in obtaining the two-piano score of the Tarantelle from the British Museum and he took it at once to Hershy Kay, whose feeling for the Gottschalk idiom had been demonstrated so brilliantly in the Cakewalk score-and who had also developed an interest in restoring "lost" works. Kay produced his now-standard reconstruction of the Tarantelle in 1957 and List gave the first performance the same year, with Richard Korn conducting, in Carnegie Hall.

Ten years later, when several Gottschalk manuscripts were offered for sale by Abrahäo de Carvalho of Rio de Janeiro, List bought them as a gift for the Americana Collection of the New York Public Library's Lincoln Center Library and Museum of the Performing Arts. The scores were those of the two marches recorded in the Turnabout album, the original piano-and-orchestra version of the Portuguese Variations, the Symphony Montevideo, Escenas Campestres, and a sketch for the Tarantelle.

Having already brought the Tarantelle into currency, List lost no time in arranging for performances of the other works. All but one were introduced in the 1969 centennial concert in New Orleans; the Marche solennelle needed more attention in the way of reconstruction, and List arranged to have a performing version prepared by Donald Hunsberger, band authority and conductor of the Eastman Wind Ensemble, in time for the recording sessions.

It was List's own idea to have The Union and the Brazilian Fantasy set for piano and orchestra. He felt The Union, in particular, "practically cried out for a larger frame," and indeed Gottschalk himself had written "Tambour," "Trombe," etc. over various sections of the piano score. The Union includes an unusually effective harmonization of The Star-Spangled Banner, and the Brazilian Fantasy is strikingly similar in its overall construction. Samuel Adler has captured the Gottschalk spirit beautifully in his arrangements, which might well become as popular as the Hershy Kay orchestration of the Tarantelle.

Naturally, List was involved in several of the special events which marked the Gottschalk centenary in 1969: he performed with the New York Philharmonic and New Orleans Philharmonic, participated in a memorial recital with fellow-pianists at Lincoln Center, played various other Gottschalk programs, and even appeared on the Ed Sullivan television show with nine of his pupils in a performance of the Jota aragonesa from The Siege of Saragossa (another reconstruction he had commissioned, this one from another of his pupils, Victor Savant). He had hoped to stage a full-scale Gottschalk "monster concert" on the anniversary of Gottschalk's death, and thought it might be done at the Eastman School (where he, Hunsberger and Adler are all faculty members), where something like the 650 performer complement of Gottschalk's own last concert in Brazil might have been assembled. Unfortunately, that did not happen: the Gottschalk commemorative concert at Eastman was, instead, a brief multi-piano program given by List and his pupils. But the Gottschalk Festival did take place in recording studios in Vienna, Berlin, and Rochester, and now the fun of it may be repeated at will by anyone who cares to make the ridiculously modest investment required for the Turnabout album.

The charming introductory remarks with which List opened the commemorative concert at Eastman, by the way, were recorded and are included in the Turnabout set. As he reminds us in those comments, in his biographical essay in the printed insert, and most pointedly in the performances themselves, fun was a quality Gottschalk held in high regard. One famous example of his sense of humor was his publication of several works under the pseudonym "Seven Octaves" with the dedication "To my dear friend L.M. Gottschalk." That same dedication, not pseudonymous but proudly signed "Eugene List," is unmistakably evident (even if not in writing) throughout this recorded "Gottschalk Festival."

==========

More music articles and reviews from AUDIO magazine.

= = = =