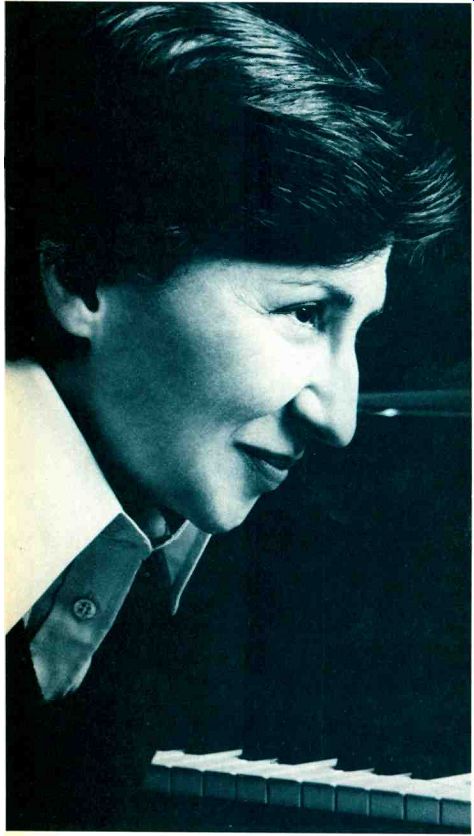

Bella Davidovich -- The Soviet Union's most prominent woman pianist prepares to conquer America.

That new Queens resident just happens to be the Soviet Union's most prominent woman pianist.

by Joseph Horowitz

In the years after the Russian Revolution, Heifetz, Horowitz, Koussevitzky, Milstein, Piatigorsky, and Rachmaninoff, among other eminent musicians, were driven west by politics and civil war-a celebrated exodus that changed the face of music in Europe and America. Half a century later, following decades of Stalinism and Cold War, another Russian exodus is underway. The most visible evidence is a handful of famous performers-Vladimir Ashkenazy, Kiril Kondrashin, Mstislav Rostropovich, Galina Vishnevskaya-who have resettled abroad without permission from home. The vast majority of the expatriates, however, are beneficiaries of a liberalized emigration policy for Jews that began around 1970, and they are coming out legally and in droves.

However crippling this migration may be for the Soviet Union, the Russians will not again take the West by storm. The American arena Heifetz and Horowitz conquered is more crowded and sophisticated than before; by the

--------

Joseph Horowitz, a noted writer on musical subjects, has investigated the Russian emigré musical community for three years.

----------

same token, too many of the immigrants seem raised in a time warp. But by any normal standard, the current influx, if not another artistic transfusion, is at least a tonic for tired blood.

One tantalizing thing about the Russians is their obscurity-even some of the most prominent in their homeland are virtually unknown here. In New York, where they regularly turn up in recital, more than a few try to compensate with exaggerated claims of past success. At least two newcomers have been presented as " Russia's leading woman violinist." Another was named " Russia's most-acclaimed woman pianist" in a wire-service story distributed nationally this year.

As it happens, neither of the violinists really lives up to such extravagant billing. The pianist, however, is the genuine article. Her name is Bella Davidovich (pronounced Da-vee-DOH-vitch), and her credentials include a first prize in the 1949 International Chopin Competition, a full professorship at the Moscow Conservatory, seventeen recordings for Melodiya, and twenty-eight consecutive annual appearances with the Leningrad Philharmonic. Probably the most practical evidence in her favor is a recital she played at the Milan Conservatory on May 26, 1977. In the audience was Jacques Leiser, the New York-based artists' manager who masterminded Lazar Berman's blitz of Europe and America.

When, having secured permission as a Jew, Davidovich left Russia in October 1978, Leiser promptly signed her up.

Working from a private tape he had obtained, he mailed cassettes of the Milan recital to conductors, impresarios, critics, and writers in the United States, Canada, and Western Europe. Shortly afterward, Philips agreed to tape her.

The result was three recordings made in March in Switzerland: the twenty-four Chopin preludes; a Schumann disc containing Carnaval and Humoreske; and one of Beethoven music, the Moonlight and Op. 31, No. 3 Sonatas plus Fu r Elise. All three are scheduled to be released in time for her Carnegie Hall debut this October 12, one of fourteen 1979-80 recitals Leiser managed to book on short notice, along with thirty-one orchestral dates.

Since last January, Davidovich has lived in a one-bedroom apartment in Kew Gardens, Queens, twelve miles east of Manhattan. To a visitor, three months ago, the apartment seemed more a way station than a new home. There was a piano, rented from Steinway, but Davidovich could not practice at full volume because the neighbors complained. The music rack held a miniature orchestral score of a Beethoven concerto. (Her full-size piano score remained in Russia.) The living room floor was bare, and so were the walls, aside from two small photographs-one of Jakov Fliere, the famous pedagogue who was her teacher at the Moscow Conservatory, the other of Yulian Sitkovetsky, her husband, a leading Soviet violinist who died of cancer in 1958 at the age of thirty-two before his fame could reach the West Under a curtainless window were two large suitcases belonging to her twenty-five-year-old son, Dmitry Sitkovetsky, also a violinist, who was out of town for the summer.

Her mother and younger sister, both of whom left Russia with her, shared an apartment two floors above.

At fifty-one, Davidovich is a small woman with reddish-brown hair and lively, experienced eyes, who looks startlingly like Chopin from the side because of her aquiline nose. Speaking through an interpreter, she apologized for the appearance of things: "The feeling here is very unusual, very uncertain.

It is like living in a suitcase." Many of the immigrants are eager talkers, buzzing with tales of Philistinism, subterfuge, and anti-Semitism. For example, Rostislav Dubinsky, formerly first violinist of the Borodin Quartet in the U.S.S.R. (now a member of the three-year-old Borodin Piano Trio), speaks of tapped telephones, undercover policemen, and cultural hatchet-men who routinely veto performances of Schoenberg, Berg, and Webern. Violinist Boris Belkin describes bribes for good behavior and crude reprisals for recalcitrance; at one point, he says, he wound up seeking refuge in a Moscow psychiatric hospital.

Davidovich, by comparison, was gracious but laconic. She volunteered little about her past, though she answered questions simply and easily and

------

Tapped telephones, undercover policemen, and cultural hatchet-men routinely veto performances of Schoenberg, Berg, Webern.

----------------

registered tired amusement whenever the subject of the Soviet bureaucracy came up.

She left Russia, she said, mainly to reunite her family: "The first reason was my son. To have only one son, to lose my husband so long ago-it was natural.

I had to move sooner or later to be with him." Dmitry (she calls him Di ma, a familiar form of the name) had abandoned the Moscow Conservatory in favor of study with Ivan Galamian at Juilliard and had tried to persuade her to emigrate when he did in May 1977. But her sister was ill at the time and unable to travel.

And Davidovich herself was reluctant at first.

"My tours to the West gave me hope of visiting Dima from time to time," she said. "The thing is, through the end of 1977 all the tours were permitted to continue, even though Di ma had left. So I had hoped for the best. But then all my 1978 tours were canceled. No explanations were given, and there was no need to ask. It was obvious Dima was the reason and that my career in Russia could only diminish. So it was clear that, unless I left, I would never see him again."

---------

"If you told Gossconcert,

'I would like to play in the West,' they would think you were crazy."

-----------------

Performing abroad had not merely been a way to visit her son. Davidovich previously had appeared frequently in Holland, occasionally in Italy, and briefly in England and France. Of playing in Amsterdam, where she had regularly appeared at the Concertgebouw, she said, "The orchestra, the managements, the audiences-everyone was supportive and enthusiastic. I played there for eleven consecutive seasons. It became a sort of celebration. The critics wrote that no other pianist from the Soviet Union had received such a welcome." To become known elsewhere in the West, she confided, had been "the dream of my life." But Gossconcert, the Soviet bureau in charge of foreign engagements, "is a very complicated system, and I never tried to understand how it works. Anyway, it is useless-it is silly.

If you told them, 'I would like to play in the West,' they would think you were crazy. Everybody wants to play in the West." She shrugged her shoulders and smiled with her eyes.

Davidovich dislikes generalizing about her playing style. Her repertoire, she pointed out, stretches from Scarlatti and Bach to such contemporary Russians as Rodion Shchedrin and Kara Karaiev and takes in all the prominent eighteenth and nineteenth-century Germans and Austrians, as well as Debussy and Ravel. At the same time, she acknowledged that her orientation might be broadly called Romantic and that there exists "a kind of popular opinion" that she specializes in Chopin. She plays nearly all of his music.

The Milan tape that Leiser converted into bookings and publicity contains the Mozart Sonata, K. 331, Mendelssohn's Variations sérieuses, Schumann's Carnaval and Abegg Variations, and six Chopin etudes: Op. 10, Nos. 3-5 and Op. 25, Nos. 1-3. All the playing is very impressive-ardent, refined, Fleet-fingered, exquisitely proportioned-but the Chopin set seems especially revealing. Davidovich's performances not only are ravishing pianistically, but convey a depth of identification that is very poignant. If one etude stands out, it is the thrice-familiar Op. 10, No. 3, in E major, a reading that aches with sadness.

The melancholic side of her Chopin, Davidovich commented, is perhaps more pronounced than it once was: "Of course, performances change a great deal over the years as a person changes and grows. At the beginning, my playing was probably more joyful, more optimistic, with brighter colors. Then something vanishes-the fearlessness of the very young-and is replaced by something else. The F minor Ballade that I played in the 1949 Warsaw competition differs greatly from what I recorded in 1910. I wouldn't say that in 1949 it was a 'happy' performance, yet it was quite different. Not as broad, not as deep." Prokofiev is another composer toward whom she feels an especially strong affinity: "To my mind, he is the greatest Russian composer of his time, and I feel very close to his world. He is a wonderfully lyrical composer. Many people don't see that. Some people try to show him as being very severe or sarcastic. But he has such depth, beyond this, and such warmth." Her repertoire includes less Prokofiev than one might expect, however.

Of the ten sonatas, Davidovich plays only Nos. 2-4; of the five concertos, only No. 1. The reason is one not every pianist cares to consider: She feels she must respect her "physical abilities." Her hands are too small for some of Prokofiev, she said. And, aside from the First, in which the orchestra can be subdued, the heavily scored concertos call for soloists with more carrying power than she feels she can muster.

All told, Davidovich performs twenty-seven works with orchestra, ranging from concertos by Bach, Haydn, and Mozart to Shostakovich's Second.

The list includes many of the nineteenth-century staples, plus a few relative surprises-Mendelssohn's G minor Concerto and Concerto for Two Pianos, Saint-Saens's Second Concerto, and the Strauss Burlesóe.

She also plays one American concerto, and in some ways it is the most intriguing of the lot: Gershwin's Concerto in F. According to Davidovich, in Russia the work is a favorite and Gershwin is by far the best-loved American composer.

She closed her eyes when she recalled her initial encounter with his music: "Before 1956 we heard non-Russian performers only on records.... Menuhin came in 1945, but I was not in Moscow at the time. Then, in 1956, a visiting American company gave the first performance in Russia of Porgy and Bess, and I went with my husband. It was out of this world-the music, the sets, the costumes.

People went absolutely wild. This was the beginning of the cultural exchange.

Later Isaac Stern came, and Munch and the Boston Symphony. These concerts were just overwhelming." Davidovich heard the Concerto in F for the first time in 1959 in Leningrad, where it was played by Ludmilla Sosena, a Soviet pianist. Through a friend, she duplicated Sosena's score and decided to learn it. When she first performed the work in 1960, that was still the only version she had heard; no recordings were available. It was not until John Browning and the Cleveland Orchestra visited Moscow in 1965 that she encountered an American interpretation. By that time, the concerto had become a regular part of her repertoire: "I played the Gershwin many times, and in many places-more frequently than any other Russian pianist. Before I left the Soviet Union, Kondrashin suggested we could play it together, but it never happened. Last February we met in Holland, following his departure from Russia, and we spoke of it again. Perhaps it will be possible now." Judging from Davidovich's remarks, the Gershwin concerto may be at least as popular in Russia as in the United States-a provocative point not so much for suggesting the range of Soviet tastes as, paradoxically, the effects of Soviet insularity. The music itself, written at the height of the '20s, is sanguine and sassy. In this country it turns up at pops concerts as a period piece and, for all its brashness, has acquired a degree of nostalgic charm. In Russia, where composers are still admonished to produce popular, affirmative art, it may well be closer to the symphonic mainstream. Kondrashin, in fact, has recorded it-a confident, flat-footed performance with the pianist Piotr Pechersky, available on Westminster Gold WG 8355.

To some of the immigrants, the commercial trappings and jet-age diversity of Western concert life seem bewildering, even threatening; they remember the security and traditionalism of the Soviet system and worry that their careers will be mislaid or their artistic bearings jostled. For others, with more sour memories of Russia, adjusting to new musical possibilities is not a worrisome by-product of the move, but a top priority. Davidovich's son belongs to the second group. Looking back, Sitkovetsky sees Soviet musicians as glorified civil servants, badgered by the state and increasingly cut off from their prerevolutionary roots.

"Generally, in Russia," he says, "professional standards have been high because of the many excellent teachers.

But this is changing, and the reason is simple. When the revolution came and the regime changed, studying possibilities at first improved for Jews and other minorities, and not all the best musicians left. The pianists who stayed included Igumnov, who taught Fliere, and Neigaus, who taught Richter and Gilels.

The violinists who stayed included Poliakin, who was the major pupil of Auer; Stoliaysky, who was David Oistakh's teacher; and Yampolsky, who taught Leonid Kogan and my father. But most of them died after World War II, and the next generation was already a pure Soviet generation, in which many musicians sought success rather than knowledge. Today there are still individual, outstanding performers. But there is no longer a 'Russian school.' " After two years in New York, a busy period during which he graduated from Juilliard and made his Carnegie Hall debut, Sitkovetsky feels he is ridding his playing of outworn romanticisms that he absorbed in Russia. "It's funny," he says, "but the Russians, despite the theory of communism, are more individualistic performers than those in the West. They cannot play chamber music, for example. They're more egocentric, more outgoing, more dramatic.

"My own playing has changed quite a bit. I played the Prokofiev First Violin Concerto at Juilliard after two months in the United States. Then I played it again about a year later, and the interpretation was totally different. The first time, it was typically Russian playing--lots of emotion, and sometimes too much, so that it was a little exaggerated.

Now I'm looking for a different kind of intensity, a more inner intensity. I'm quite sure my mother, too, will in some ways be influenced and change. It happens to all the Russians here. Even Rostropovich plays quite differently than he used to." Davidovich responds to such opinions with smiles and affectionate motherly shrugs. She does not agree that Russia's nourishing musical traditions have lapsed and believes that increased access to recordings and radio broadcasts has helped open up the Moscow Conservatory. As for changes in Dmitry's style, she has noticed a difference but questions its source.

"Unfortunately, I didn't get to hear Dima when he played in New York because I was in Amsterdam at the time," she said. "But I heard him play a

----------------

The Gershwin concerto may be at least as popular in Russia as in the United States.

-----------

little Prokofiev in rehearsal, and to my mind he has started to play much more warmly. Whether it's his age or the experience of being alone in a new country, I don't know. The individual personality, the artistic soul of a person, always undergoes certain transformations over the years, regardless of whether he lives in the Soviet Union or the United States.

Even back home, we were influenced by visiting artists. The arrival of Glenn Gould in Moscow, for instance, caused a revolution in the interpretation of Bach.

All the students took their feet off the pedals and played staccato. It became impossible to teach Bach." And what of Dmitry's prediction that her own style of playing will change? Davidovich laughed and flung her arms into the air: "When you have a son of twenty-five, it is hard to say anything. The musical life in the West is very lively, and I am eager to see and hear as much as possible. It's very hard to foresee what will happen. At present, I'm just the same person as before."

HF

(High Fidelity, Oct. 1979)

Also see:

Eight (or So) Records to Judge Speakers