.

by Patrick J. Smith

London's Lucrezia Borgia is distinguished by Richard Bonynge's crisp yet flexible conducting and Joan Sutherland's magisterial, vocally robust heroine.

Donizetti's Lucrezia Borgia (1833) is not one of his best scores, but it is a good deal better than his average ones. This is so less because of the music Donizetti provided than because of the grisly, super-melodramatic plot Felice Romani fashioned from the Victor Hugo play. Emotion is at center stage, and-given the necessity for plenty of vocal opportunities-the story moves with concision and rapidity, ending with the villain Alfonso, Duke of Ferrara, left alive, in the company of his wife and her (not his) son, both dead on-stage, and five more people poisoned off-stage. The plot has as much coherence as most suspense movies and a trifle less believability, but Romani knew enough to give his heroine the chance to show a variety of emotions: mother love, family pride, fury, hatred, fear, triumph, and, finally, grief. He is aided by the ambiguity of the story, for son Gennaro is unaware of the identity of his mother and adores her in the oedipal sense until she enlightens him in the final duet, when he is dying.

Donizetti pours forth a steady DONIZETTI: Lucrezia Borgia.

CAST: Lucrezia Maffio Orsini Gennaro Rustighello Liverotto Vi'ellozzo Don Alfonso A Servant Joan Sutherland (s)

Marilyn Home (ms)

Giacomo Aragall (t)

Graeme Ewer (t)

Graham Clark (t)

Piero de Palma (t)

ingvar Wixell (b)

David Wilson-Johnson (b)

Gazella Lieuwe Visser (bs)

Petrucci John Brócheler (bs)

Astolfo Nicola Zaccaria (bs)

Gubetta Richard Van Allan (bs)

National Philharmonic Orchestra, London Opera Chorus (director: Terry Edwards), Richard Bonynge, cond. [James Mallinson, prod.]

LONDON OSA 13129, $26.94 (three discs, automatic sequence).

Tape: 05A5 13129, $26.94 (three cassettes).

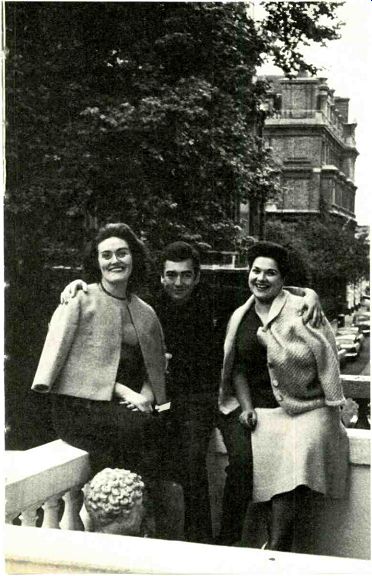

Joan Sutherland, Richard Bonynge, and Marilyn Horne on a London street stream of melody of a positive and optimistic sort-as was his habit-and the very dynamic, upbeat quality of the music serves to heighten tension when combined with the largely unrelieved bleakness of the plot.

The music thus achieves a dramatic function that I feel eludes it in Donizetti's straightforward dramas (e.g., Roberto Devereux), in which its very life-enhancing qualities work against the more elevated drama of the story. In much the same way, the frenetic partying of Orsini and his friends, in their inane superficiality, is deliberately set against the backdrop of the deadly Borgias and culminates in the last scene, in which the roisterers joyously and unknowingly quaff their poisoned cups of wine. (The dramatic irony of the scene was reused, in altered form, by Scribe and Meyerbeer in the last scene of Le Prophétc.) Lucrezia Borgia has never been particularly successful, even among Donizetti's operas, I think because it is the Donizetti opera that most clearly points the way to the middle-Verdi melodramas, and these effectively eclipsed it. Verdi's handling of a swiftly moving and more tightly constructed story of heightened emotion, in Macbeth and more centrally in Rigoletto and Un Ballo in maschera, is everywhere more persuasive. Yet the seeds for those works and others are contained here. Indeed, the handling of the Borgia henchmen throughout Lucrezia is directly analogous to Rigoletto, and the setting of Act I, Scene 3 (Act II, Scene 3 in the London recording, which numbers the prologue as Act I), with its repeated musical figure underlying the conversation of Rustighello and Astolfo, could be the model for the great Sparafucile/ Rigoletto scene in its evocation of insinuated menace.

London's new recording of Lucrezia, while not ideal, does bring out strongly the febrile vitality that infuses the work. Its only rival is the RCA recording with Montserrat Caballé, reviewed here by Conrad L. Osborne in 1967. In at least one respect, the RCA recording is clearly superior: the Gennaro of Alfredo Kraus. Although Kraus does not possess a luscious voice, his sense of phrase and style is so apt and beautiful that it is a constant pleasure to hear--particularly today, when such values, among leading tenors, are in very short supply. But Gennaro is, as a character, a near nullity, and Donizetti has not given him a role commensurate with his mother's.

The question of editions is a factor.

Donizetti, in keeping with nineteenth-century performance practice, altered the score for specific performances. At her insistence, he provided the first Lucrezia, Henriette Méric-Lalande, a final coloratura death aria, which he later excised. Both recorded sopranos side with Méric-Lalande rather than Donizetti and include it. In 1840, he added a cabaletta to Lucrezia's aria in the prologue; Caballé sings it, but Joan Sutherland, oddly, does not. Richard Bonynge inserts a tenor aria in Act II, written for Nicolai Ivanoff, that the conductor found in the Morgan Library in New York (keeping in, too, the Gennaro/Orsini duet dropped when the aria was sung), and also includes the brief tenor arioso from Donizetti's refashioning of the last scene; neither of these tenor additions is in the RCA. Bonynge, however, makes several small cuts in the chorus parts, uncut in the RCA. His performance also features occasional differences in note values, as well as cymbal crashes in the orchestrations at various spots not found in the RCA. As usual with him, second verses of arias are embellished.

The strengths of the London recording lie in the aforementioned energy-in Bonynge's conducting and in Sutherland's vocalism. Bonynge plays for drive but, at the same time, demonstrates the flexibility of tempo and plasticity of phrase that enliven his best ballet recordings. His attention to clean staccato orchestral passages give many sections a buoyancy and crispness that propels the music onward, and in this he is aided by the lithe, spirited, and youthful-sounding London Opera Chorus.

RCA's Jonel Perlea is no match-though consistently forceful, he has none of the nuance Bonynge brings to the opera.

Sutherland is Sutherland, which means that most of Lucrezia's emotional variety goes unrealized, except for some swooning phrasing meant to suggest feminine fragility. She cannot, for instance, really convey outrage at the beginning of her central scene with her husband, and though her enunciation is, for her, quite good, she rarely sings anything under mezzo-forte. Her voice, nevertheless, sounds in surprisingly good shape (the recording was made in August 1977), with a firmness of tone and an ongoing thrust reminiscent of her best vocal days, and her coloratura and trill remain solid. She brings an appropriate magisterial, almost glacial, stature to her outburst at her husband in their scene, as well as in the final scene, tempering it there to an affecting farewell to her son. The noble imperturbability of the character is well set forward. Those who admire Caballé will perhaps prefer her vocalism, which is more varied, but I generally agree with Osborné s strictures as to her technique, and she was in subpar vocal estate at the time of the recording.

The subtleties Bonynge brings to the orchestral playing are not reflected in the solo work. Vocally, the opera is played for maximum gut wallop. Giacomo Aragall simply cannot sing at any other level but forte (his isolated attempts at soft singing are embarrassing). Moreover, his major faults-an in-built sob and the frequent inability to strike the center of the pitch--while less evident than in some of his live performances, are for me a major distraction and annoyance, although others may be less bothered. It is ironic that he, and not Kraus, was given the opportunity to sing the extra tenor music. Ingvar Wixell's baritone does not have the range or flexibility of his RCA counterpart, Ezio Flagello, but he does bring to Alfonso a dark and consistently focused intensity that is exactly right for that unregenerate black hat. His rendition of the rousing cabaletta to his Act I aria is electrifying and is splendidly partnered by Bonynge's rhythmically vital (and prominent) accompaniment.

Marilyn Home's singing of the trouser role of Maffio Orsini is another in the long list of performance enigmas by this gifted artist. It is quite well sung, even if the celebrated last act ballata needs more quickness and élan, and it lies well for her voice, but she does not give me any picture of a young and insouciant rakehell. The volume and weight of the voice are wrong, and what results is singing for singing's sake rather than any portrayal of character.

RCA's Shirley Verrett, despite her curious Italian pronunciation, is much more in the trouser--role tradition and sings equally well.

The supporting cast (numerous, but minor in contribution) is adequate overall.

The recording is close-miked as to the principals (Home's breathiness is very evident) and lacks a sense of aural depth, but the orchestra can be more clearly heard than on RCA. Exemplary notes-which should set a standard for the industry--by Jeremy Commons.

(High Fidelity, Oct. 1979)

Also see:

The Silent Lass with a Strenuous Air [Richard Strauss in the mid-Thirties]