New designs are springing up like mushrooms; a former loudspeaker designer gives you his thoughts on the whys and bows of choosing and using them.

by C. Victor Campos

Few developments in recent high fidelity history have been as visible--even as touted-as the equivocally named subwoofer. In the strict sense, a subwoofer is a low-frequency driver system designed to extend the range of an already-adequate speaker into that bottom audible octave where costs are high (because the long wavelengths imply oversized reproducers) and benefits low (because so little program material includes reproducible information in the bottom octave). The term has, however, come to mean any low-frequency-only reproducer, even if its primary objective is to reproduce what would normally be the woofer range of the speaker systems it supplements.

In particular, the subwoofer / "satellite" combinations-often using mini-speakers of the type that have proliferated in high fidelity and auto sound as the main speaker pair--are enjoying--considerable vogue. Some combinations are designed as integral ensembles, some as mix-and-match separates. But even without the inherent limitations on deep bass posed by the mini-speaker format, there is rationale for add-on subwoofers.

They permit the speaker buyer to make his own decision about the octave between, say, 25 and 50 Hz, whose inclusion can easily double the price of a typical quality loudspeaker. Thus the current rash of subwoofer designs brings a new degree of flexibility to the tailoring of individual stereo systems.

The word "new," however, deserves some qualification: The first noticeable demand for subwoofers was in response to early so-called full-range ...

-------

C. Victor Campos, probably best known to our readers for his long association with KLH and AR (and, to Boston readers, for his pioneering audio show on station 1V'GBH-FM), has transferred his activities to Washington, I.C., and the Electronic Industries Association.

---------

... electrostatics, notably the Quad and the KLH Nine. Although they reproduced the whole audible range, their power-handling capability was very limited when they were called upon to reproduce frequencies below 120 hz or so.

And their intrinsically low efficiency demanded substantial power for reasonable volume levels, particularly in large rooms. This combination of factors required extraordinary measures: supplemental low-bass drivers. The first speakers to be pressed into this service were the ARI W and the KU I One, Two, and Three--all of which were woofers only and the first of the acoustic-suspension designs on the market. (I purposely ignore earlier common-bass woofers, crossed over at relatively high frequencies to tiny stereo "satellites" whose bandwidth did not encompass the bass to begin with.) These, along with electronic crossovers of that era (Marantz and Heathkit) and biamplification, made the electrostatic/subwoofer combination feasible.

The results were almost miraculous: The bass suddenly became robust, and the overall power-handling capability of the electrostatics appeared to increase phenomenally. In fact, only minor problems presented themselves, primarily that of achieving satisfactory blend between the subwoofers and the "dipoles" (which electrostatics generally are) due to the physical separation of the driver elements in the crossover region, and the difficulty of matching the acoustic levels and the acoustic slopes of the two sources in the crossover region.

Over the years, improvements in woofer manufacture and materials extended bass response sufficiently to make the use of subwoofers for other than electrostatic systems a curiosity. Since the vast majority of available source material rarely has much energy below 50 hz, attempts to reproduce the bottom octave of the audio spectrum proved an almost worthless task.

The recording, cutting, and pressing technologies also improved, however, putting extended low-frequency information onto more and more records. Then the brilliant and punchy "direct cut" records began to exceed the low-frequency reproducing capabilities of most loudspeakers, almost requiring the extension of this capability. In addition, the many owners of mini-speakers with excellent response down to 100-150 hz welcomed the flexibility of a sub-woofer that could extend response into the nether regions without pre-empting Floor space at the focus of the listening room.

The only function of a true sub-woofer is to supplement a standard system at the lowest frequencies-below about 100 hz, though some make their contribution primarily below 75 Hz. In this range, sound sources cannot be localized and subwoofer placement is not critical, permitting use of a common unit for both channels in stereo systems.

Above 100 Hz, however, use of separate subwoofers, placed reasonably close to the speakers they supplement, becomes increasingly important for good stereo localization and image stability. Whatever their effective frequency range, sub-woofers are available in many formats and designs, ranging from classic acoustic-suspension formulas to complicated computer-aided vented designs to purely electronic ones that, in effect, boost amplifier power below the woofers' resonance frequency to compensate for their inherent rolloff.

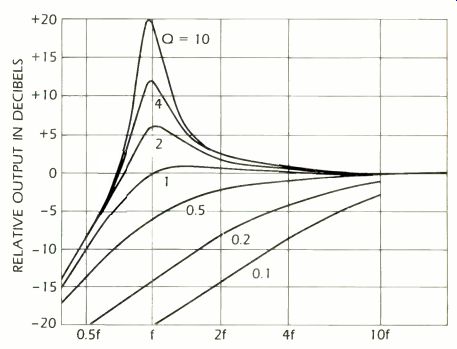

If you are contemplating the purchase of a subwoofer, your big question should be: "How do I know that a sub-woofer will, in fact, extend my low-frequency response?" fortunately, the behavior of loudspeakers at low frequencies can be defined quite adequately by the "Q" of the system and by its point of resonance. Q may be considered a numerical statement of the behavior and output of a speaker at and near its resonance frequency, as shown in the accompanying curves. The higher the Q, the higher the speaker's output will beat resonance, and the less controlled its behavior when compared to the response just above resonance. Generally speaking, loudspeakers with a Q higher than I will tend to be boomy and exhibit "hangover": blurred, indistinct attack on transients. The ideal Q lies between 0.75 and 1, where bass response is Flat at resonance, with no evidence of hangover. As the Q begins to fall below 0.75, the output at resonance and above actually decreases-and to quite a significant extent.

At a Q of 0.5, known as "critical damping," the bass is down 6 dB at resonance, and although it might then be defined as "very tight," the rolloff with such over-damping doesn't really result in cleaner bass.

The second parameter of importance, resonance frequency, defines the point at which (assuming a Q of about 1) the loudspeaker reaches its maximum excursion and its lowest frequency of unattenuated output. All speakers, regardless of design, roll off at a predictable rate below the lowest resonance point. Closed-box systems, such as acoustic-suspension designs, attenuate input at a rate of 12 dB per octave below resonance; vented speakers roll off at 18 dB per octave.

Knowing these two parameters, anyone can accurately predict the performance of any woofer or subwoofer at very low frequencies-and how much improvement the subwoofer will provide to the low end of a given system. In speakers incorporating 10- or 12-inch woofers, it is not uncommon to find resonances between 40 and 45 Hz, with a Q of about 1. If you want to improve such a system, the subwoofer must have a resonance at 25 to 30 Hz with a Q of I, or the enhancement of low frequencies may be more imaginary than real. For such a resonance (with constant acoustic output above it), however, the excursion of the subwoofer cone must increase substantially: It must quadruple its excursion for each added octave of bass response. To keep distortion low, the length of the voice coil must increase so that the same amount of coil will always be in the gap, even during maximum cone excursions. Under such circumstances, and assuming good power-handling capability, there is enough voice coil out of the magnetic gap (enough "overhang") to lower the efficiency of the system in comparison to one of similar size and cone area but with a higher resonance.

--- Response curves for differing values of Q show that at a

Q of 0.75 to 1 a speaker's output at resonance frequency (f_r)

is flat in relation to output above. ---

Addressing themselves to the complicated interrelation of distortion, efficiency, and bandwidth, subwoofer designers have opted for multiple drivers, large-area cone drivers, and even built-in amplifiers, which help to ensure both that the driver will receive adequate power and that its output can easily be matched to that of the system it supplements. There are, of course, advantages and disadvantages to all of the approaches; only the user can make the correct choice for his particular needs.

A few complete loudspeaker systems on the market can be said to have integral subwoofers since their low-frequency response cannot readily be enhanced by an additional device. The Infinity 4.5 and the AR-9, for examples, employ techniques that extend their woofer response down to 30 Hz and below in enclosures that are not especially large when compared to most large speakers of more limited low-frequency response. In these systems, the designers have already determined for you the correct balance throughout the spectrum, including the very low frequencies; although adjustments may be possible (or provided), your starting point has already been very well defined.

Knowledge of your starting point is important in adding any subwoofer since the balance and blend between it and the rest of the system are critical to good results. They are, at best, tricky to achieve without the aid of instruments; the ear can be fooled easily, particularly during the excitement that such an addition can generate. Many subwoofer owners have mistaken an elevated low-frequency response for extended bass when, in fact, the subwoofer may have added only 5 Hz or less to the response of the system. If response irregularities due to reflections from room surfaces fall at slightly different frequencies due to differences in room placement, the bass of the subwoofer may sound different from that of the main speaker without extending it; if the subwoofer simply delivers 3 to 5 dB more output than the rest of the system, it will sound "bassier" but can hardly be said to serve the cause of fidelity. So, careful initial level adjustment and correct placement of the sub-woofer to minimize peaks and dips in its response are at least as vital to maximum performance as careful product selection. And the guidelines available from manufacturers for best use of their sub-woofers should be taken to heart.

Finally, pay close attention to the blend between the subwoofer and the woofer-and, particularly, to the juxtaposition of the subwoofer and the speaker system. Phasing anomalies in the crossover region are especially problematical with dipole radiators, such as electrostatics. Careful positioning of all the elements and selection of gentle crossover slopes (if you have a choice, as you do with some electronic crossovers used for biamplification) usually are helpful. Remember, too, that the lower the crossover frequency, the less noticeable phase effects will be because of the longer wavelengths involved.

But whatever specific objectives you want to achieve, watch your Qs and resonances.

HF

(High Fidelity, Oct. 1979)

Also see: