Béla

Bartók A Centenary Tribute

BÉLA BARTÓK, who died in New York's West Side Hospital on September26, 1945, was born in Nagyszentmiklós, Transylvania (then Hungary, now Romania), on March 25, 1881.

This month we could also have celebrated the Telemann tercentenary; with no slight to that worthy composer intended, we've chosen instead to concentrate on Bartók.

Though--contrary to some early predictions--the composer has yet to take his place as the fourth "B" behind Bach, Beethoven, and Brahms, he has certainly held his own in the company of the other great twentieth-century innovators, Stravinsky and Schoenberg. And as will be stressed repeatedly in the following pages, he was not just a composer, however great, but an excellent pianist and a pioneering ethnomusicologist. To dabble in three such related pursuits is not unusual; to achieve in even one of them the absolute mastery this versatile and consummate musician achieved in all three is rare indeed.

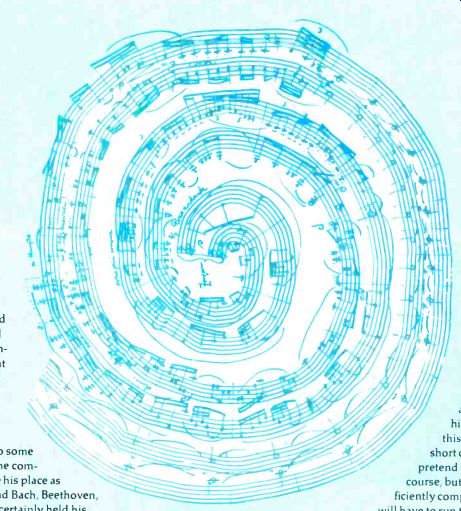

This is not HIGH FIDELITY'S first brush with Bartók; longtime readers will recall Alfred Frankenstein's October 1956 discography. That issue brought to light on its cover, no less--Robert Berény's The second of Bartók's Seven Sketches for piano, "Seesaw," further captioned, "In memoriam perpetuam horia rum 6, 7, 8, 9, 10, 11 p.m. 16.11.1909"-in its dozing (un)final measures, an obvious spoof of "perpetual motion." 1913 oil portrait of the composer, previously thought to have been destroyed; in fact, as was subsequently determined, it had been stolen from the artist in 1915 and bought at auction following the culprit's 1953 death. Ownership of the painting remains in dispute to this day, and our use of it involved us briefly in the interminable tangle of litigation that has enmeshed the Bartók estate.

Nothing daunted, we take up the cudgel again. And again, the centerpiece of our tribute is a discography, this time by Jeremy Noble, whom we are trying to lure out of "retirement." (Inauspiciously, he was last heard muttering something about having let himself be talked into this.) No such survey short of book length can pretend to completeness, of course, but this one is sufficiently comprehensive that we will have to run to two installments, with the second to follow next month's celebration of our own thirtieth anniversary.

In a separate survey, David Hamilton discusses Bartók's own recordings and, more generally, his pianism. Paul Henry Lang, who witnessed Bartók's career both in midflight, in Budapest, and at its tragic end, in New York, here adds perspective to the unrelievedly bleak picture we've been given of the composer's last years. And finally--first, actually--we welcome writer and television producer Curtis W. Davis to share memories and magnificent photographs of his recent trip to Eastern Europe "in search of Béla Bartók."

J.R.O.

+++++++++++++++++

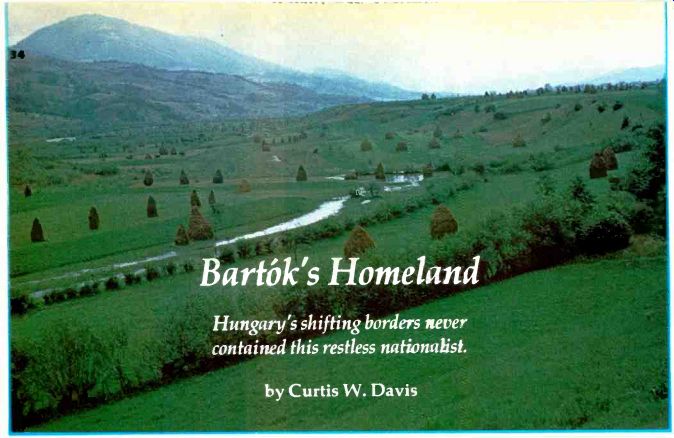

Bártok’s. Homeland-- Hungary shifting borders never contained this restless nationals.

by Curtis W. Davis

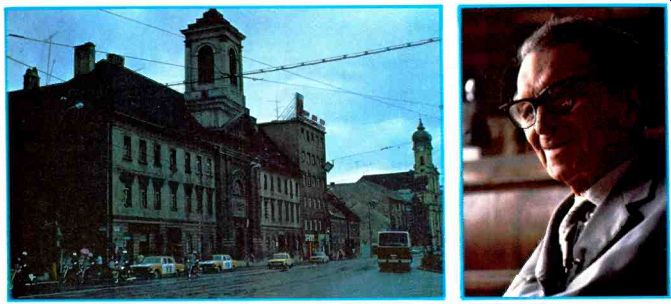

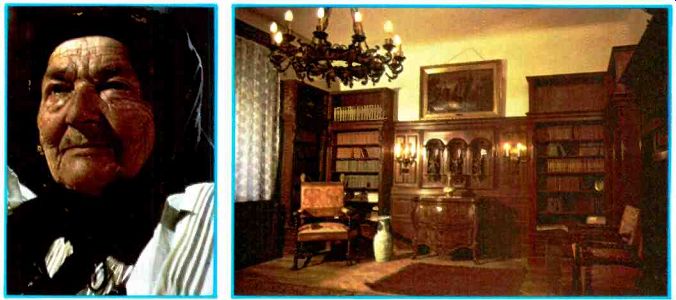

A genius is a wonder, just like the P-] other incomprehensible things of this world," says Professor Antal Molnár (below), ninety-one this year, whose friendship with Béla Bartók dates back to before World War I. Molnár was the violist of the celebrated Waldbauer Quartet that, in the first joint Kodály/ Bartók concerts in March 1910, premiered both composers' First String Quartets. Of Bartók's work Molnár adds, "This was a revolution. At first the music was unintelligible. Around the thirtieth or fortieth rehearsal we began to see the light. By the 100th we knew we were playing a masterpiece and its author must be a genius." The event marked Bartók's coming of age as a composer.

Born in Eastern Hungary in a town now part of Romania, Bartók spent his teenage years in Pozsony, the former Hungarian provincial capital. His widowed mother taught school, and the family lived in a second-floor front apartment of the square gray building (below) that still stands on Korhaz utca ( Hospital Street) opposite a busy shopping center. Pozsony, known to the Germans as Pressburg, is now part of Czechoslovakia and called Bratislava.

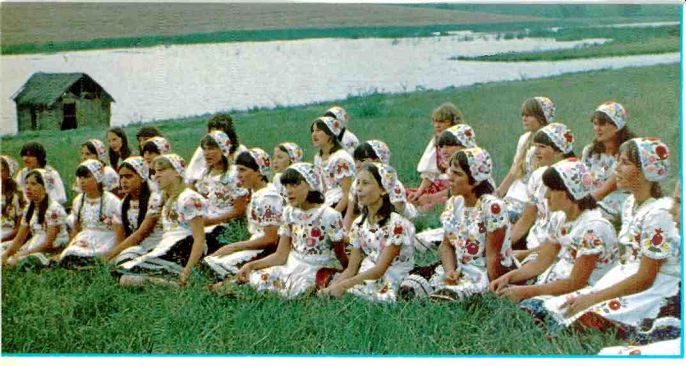

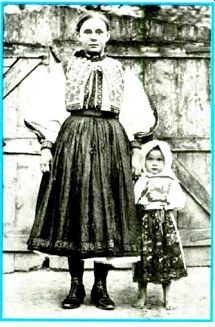

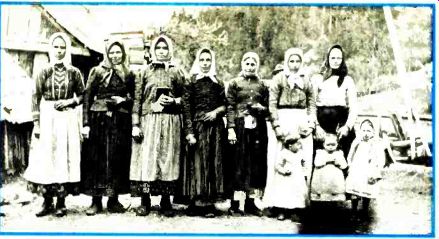

After World War I, Hungary was stripped of much territory. But Bartók found such arbitrary boundary lines separating Hungarians from Slovaks, Serbs, Croats, and Romanians irrelevant. For more than thirty years he traveled across this fertile land, cultivated for centuries, seeking out the musical memories of these tillers of the soil. The province of Maramures (above) was one of his frequent stops.

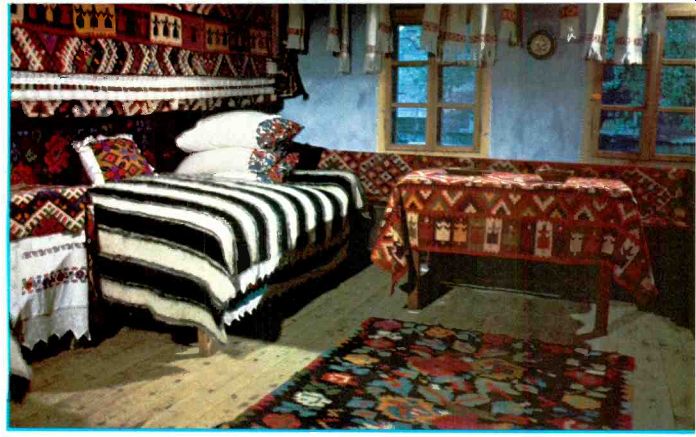

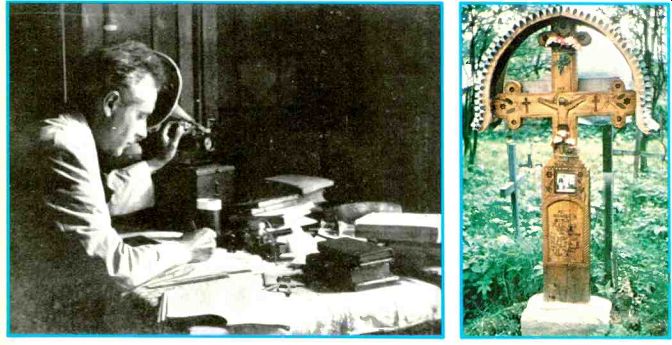

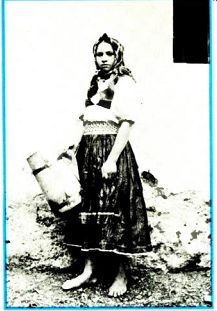

Bartók was never at home in the stiff formal salons and studies of Central Europe (below). He preferred instead the rural villages, especially in his beloved Transylvania, where farmers and their wives could gather to sing for him, play flutes and fiddles, and tell tales. He took all this down on his Edison recorder, accumulating nearly 8,000 cylinders between 1905 and 1936 (of which some 4,500 survive). He carted his precious blanks over many miles of rocky, rut-gouged roads and returned home to transcribe the music in meticulous notation (next page). He also took along a camera to record a wealth of images, some of which adorn later pages in this issue.

Near Kórósfó, north of Cluj in Romania, lives Kata Marton Ambrusné (below), at eighty-two one of the last survivors among those who sang for Bartók. It was in Kórósfó that he had his elaborately carved peasant furniture made in 1907, and the woodworking craft is still expertly practiced there. I cannot forget the old woman's friendliness-we called her familiarly "Kataneny"-or her fine voice and strong embrace. Nor will I forget the taste of her golden chicken-barley soup served on the undecorated porch of her plain wooden home; the railing served as our table, while the fragrant odor of the grape arbor overhead mixed with that of the chickens, horses, and other livestock in a veritable Bartókian epiphany.

Farther north in Maramures, in Bogdan-Voda, stands a farmhouse whose family room (above) once served as a gathering point for villagers invited there to share their music with Bartók.

These pictures, and the associated memories, are the product of an expedition I undertook to Hungary last summer to retrace just a few of Bartók's steps as part of the production ofa film documentary I was writing and directing-a coproduction with the CBC, Toronto, and MTV, Budapest-to commemorate his centenary. My thoughts turned again and again to the heartbreak he must have felt upon deciding to leave Hungary at the outbreak of World War 2. I often thought, too, of the cemetery we visited in Maramures (below), which to me symbolizes that living culture of which he preserved so much in the nick of time.

Bartók wrote in virtually every form, and the Hungarian Children's Choir (above) sings many of his subtly complex re-workings of songs about bread baking, courtship, and sorrow.

The value of his masterpieces is immense, but his legacy is greater still, for he was nourished by the oldest and deepest roots of his people, absorbing and giving back in his music the essence of that great heritage. "The people of the world recognize themselves in this music," says Yehudi Menuhin, to which Prof. Molnár would add, "Bartók wanted to raise the whole of mankind to that level where there is no more poverty or starvation, where people do not kill other people. If we analyze his art deeply, we will find that this is its final meaning." HF Curtis Davis served as co-producer and principal writer of the recent television series The Music of Man and, together with Yehudi Menuhin, wrote the accompanying book. He is currently working on a biography of Leopold Stokowski.

++++++++++++++

Bartók at Columbia

The proud pilgrim's troubled final years as seen by one who tried--with partial success--to help.

by Paul Henry Lang

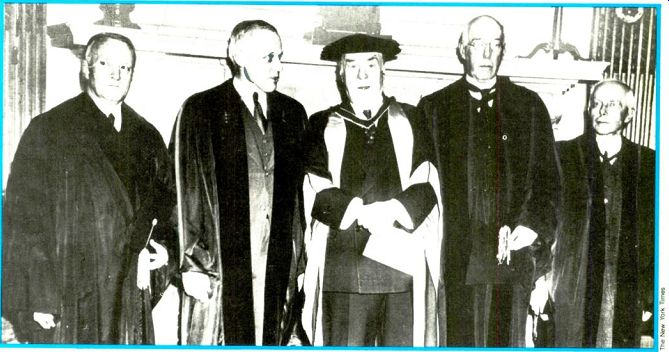

------------- Nicholas Murray Butler (center), Columbia University president,

with the November 1940 recipients of honorary doctorates (from left): French

historian Paul Hazard, American physicist Karl T. Compton, British jurist Sir

Cecil Thomas Carr, and Bartók.

It sometimes appears that man's worst scourges are not accidental catastrophes that engulf us indiscriminately, but tragedies measured to each of us individually, tragedies that complete our own little destinies. Something of the kind can be seen in the fate of Béla Bartók. His was a strong soul in a body frail but intense, with penetrating bright eyes, lively gestures, precise and ready words, always alert and courageous, as if the whole man were the blade of intelligence drawn from its sheath. Both war and injustice-and his firm response-rudely disrupted his life's course.

Bartók started his career at a time and place auspicious for a young and gifted musician. At the turn of the century there still existed in Central Europe, notably in Hungary, a great liberal tradition that nourished the arts. Wealth and fame seldom companion the service of serious and forward-looking art, but in those days an artist and scholar could indeed live and work in peace, his activity sanctioned even by officialdom. Though as a "radically modern" composer Bartók did meet opposition-often violen-the steadily rose in status; some of his compositions were published, his concert tours were successful, and he became professor of piano at the Royal Academy of Music in Budapest. Universal Edition of Vienna welcomed him into a company that would come to include the elite of twentieth-century music: Mahler, Schoenberg, and other leading lights of the age.

Acclaim greeted not only the creative artist and the piano virtuoso, but also the path-breaking scholar, the folklorist, who attacked a vast fortress of misconceptions. He demolished bit by bit the picture the world had of Hungarian music as reflected in the Hungarian dances, rhapsodies, csárda scenes, and other fabricated urban export articles. By collecting, transcribing, and publishing in impeccably researched 'and annotated collections the unspoiled music of the peasantry, he revealed the true national heritage. This was iconoclasm, albeit in the best sense of the word, and it did not sit well with many people, especially when he explored the music of Czechoslovakia, Romania, and other neighboring nations then regarded as enemies of a Hungary dismembered by the treaty of Trianon. At the outbreak of the Second World War, his position in Hungarian and European music was so assured that nothing could hurt him. So why was it that he left the security of Budapest and set sail for the New World, arriving in New York in October 1940 as a little-appreciated and impecunious refugee? A man can be characterized by the relationship of his intellectual and moral qualities; when equally elevated, they are in balance, yielding a rare integrity and nobility. Such a noble mind was Bartók's: He could see the truth and had the courage to hew to it and to speak it.

And when the evils of Nazism plunged Europe, and subsequently the entire world, into misery and anguish, he voluntarily relinquished his prominent position, because he refused to have commerce with the legions of hatred and destruction. Had he but taken a passive attitude, like Richard Strauss, he could have remained the commanding musical figure in Hungary, for he could not have been denounced as a Kulturbolschevik or non-Aryan. But he refused to condone evil, raised his voice in the defense of friends and colleagues now hunted and humiliated, forbade that his works be performed in Germany, and chose exile in defense of principle.

The man who arrived in New York was a little-known pilgrim. It is sadly ironical and not a little uncomfortable to recall that the New York newspapers, announcing the arrival of several musicians seeking refuge in this country, casually mentioned his name as a "Hungarian pianist and composer," singling out from the group Vladimir Golschmann, a perfectly decent but minor musician, as the most important new arrival. It was painfully clear that Bartók had to start life anew, from the bottom.

Yet--and this is not generally known-the difficulties he encountered were to a considerable extent of his own making; his integrity was so fierce that he could not make even reasonable compromises. There were enlightened musicians in this country who fully realized his standing in twentieth-century music, and there were offers of good positional--ways to teach composition. His reasons for refusing are not altogether clear.

He was, however, a "national" composer, his idiom outside the international current of contemporary music, and he may have felt that his own style would conflict with teaching composition in a foreign setting. I believe he was unwilling also to expose young students to so decided an influence, remembering his own apprenticeship at the academy under the thoroughly Germanic Hans Koessler-a period he later considered a false start. He wanted to teach piano or ethnomusicology, but the country was then overstaffed with piano teachers, while ethnomusicology was almost totally unknown in 1940. There was not a single chair in our universities for this discipline. We did have a few able scholars hidden in anthropology departments, yet anthropology itself was then a new discipline; an opening for a musical folklorist was indeed a rarity.

There was, however, a first-class ethnomusicologist at Columbia University: George Herzog, a professor in the anthropology department, was working in the field of American Indian music and linguistics. Based on this contact, a

--- Bartók's integrity was so fierce that he could not make even reasonable compromises. ---

genial conspiracy was initiated. Such fellow Hungarians as Fritz Reiner, Joseph Szigeti, and Eugene Ormandy got the money. Herzog and I, who had known Bartók since our student days at the conservatory, did the rest, aided by Douglas Moore. Bartók was appointed research fellow in Columbia's department of anthropology without teaching duties. The university had access to a large collection of Serbo-Croatian folk music, and he went to work with gusto, transcribing and analyzing it with a view to publication. (Columbia University Press, after agonizing delays, published the fine volume after his death.) All this had to be done informally and sub rosa, as this proud man would not accept anything resembling charity.

During his stay at Columbia, we "colleagues" had a very pleasant relationship with Bartók. Although he was an almost fanatically private person, he often visited the music department. We had small dinner parties at the faculty club or in our homes, and we hung on his words, because most of us realized that we were in the presence of genius. And when, at the piano, he would show us some fabulous rhythmic combinations he had found in his research (he very seldom spoke of his own music), we were enthralled. He, in turn, always prodded Herzog to show him the results of his research in American Indian music, which interested him very much.

Then things took a bad turn. By 1942 the funds gave out, and what with wartime conditions, the university felt unable to budget a nonteaching position.

Performances of his work were few, as were concert engagements-and both, it was only later known, were pitifully underpaid. Our renewed efforts to persuade him to accept a position as teacher of composition were unavailing.

This episode in Bartók's life' in America has been misinterpreted. Understandably, we did not want to reveal the background of his appointment, and Columbia was accused of ignorance and heartlessness, even though it graciously played along with the conspirators, bending the rules to do so, and made an appointment that was--to say the least--unconventional. It also bestowed on Bartók the honorary degree of doctor of music, which pleased him very much. The chief source of the misunderstandings of his stay in the United States was a "biography" by Agatha Fassett, full of inaccuracies, lengthy quoted conversations that never took place, and all sorts of hearsay anecdotes. The 1954 edition of Grove's Dictionary of Music and Musicians, displaying editor Eric Blom's well-known dislike for everything American, called Bartók's treatment in this country "shameful," though the article admits that "of how [he[ lived during his last years we still have no clear picture." Beyond question, all of us, caught up in our own problems and trying to cope with wartime restrictions, failed to improve his lot, and we deeply regret this failure. ASCAP, in sharp contrast to the behavior of his publishers and managers, came generously to his assistance when apprised of the situation, but by then it was too late; leukemia soon claimed its victim. Those who see nothing but deplorable indifference toward a great artist overlook the difficult and confused situation-and Bartók's own inflexible resistance to accepting any contribution not earned. The privacy he so ardently desired became a loneliness no one could breach. Only after his death did Victor Bator, his Hungarian-born friend, mentor, and executor, discover the extent of his deprivation.

Bartók's persevering idealism counted on no reward; through exile and illness, living from hand to mouth, it kept him above the waves, sustaining his creative activity until his dying day. In the end, he succumbed, the soul vanquished by the frail organism that had never really contained it. The world that showers its gratitude on the fashionable idols of the day does not understand artistic and moral integrity of so stern a nature; his funeral was attended by a mere handful. Succeeding generations may consider him another of those geniuses an unresponsive society has permitted to perish, yet perhaps it was inevitable that a man of his character would, like many others, appear to be fate's victim. Whatever his hardships, however deep his disappointments, his art was triumphant. Even in the Concerto for Orchestra, composed in the shadow of death, that vernal energy that always characterized his activity still shows through, unbroken, without resignation-indeed, transfigured.

HF

+++++++++++++++++++++++++

Bartók at the Piano

A skimpy but valuable recorded legacy surveyed.

by David Hamilton

----

above: Not given to public displays of whimsy (except in his music), Bartók hints at a smile in this 1901 photograph, and his subsequent doodles seem to confirm the mood.

Most of the great composers have engaged with music in more than one way. Many have also been performers, and that is still a lively tradition. As essayists and critics, composers have written, illuminatingly and sometimes scathingly, about their art and its practitioners. Many have taught young composers and performers. Not a few have indertaken scholarly research and theoretical speculation. Obviously, such

compound attachments to music often interact, enriching each other. The performer's familiarity with an instrument stimulates the composer's imagination; the composer's insight brings a special authority to his criticism; the scholar's discoveries suggest new compositional techniques or materials.

No richer exemplar of the virtues of such a manifold musical life can be found than Béla Bartók. He was one of the major figures in twentieth-century composition. He was also a pianist of the first rank. His studies in the folk music of his native Hungary and surrounding lands, a significant contribution to the then still young discipline of ethnomusicology, were absolutely decisive for the direction of his work as a composer.

Although he considered composition un-teachable, Bartók was for more than twenty-five years professor of piano at the Budapest Academy and, as an offshoot of th's activity, made performing editions of much of the standard keyboard literature; his intimate knowledge of the instrument and its technique was surpassed only by his daring and inventiveness in wresting novel sonorities from its hammers and strings.

The several aspects of this career are, for the most part, amply documented. Bartók's music is in print and has been performed frequently and well on records. (See Jeremy Noble's discography, following.) His essays and a goc.d selection of letters have been translated into English ( St. Martin's Press). His ethno-musicological works, only partly published in his lifetime, are still appearing; the melodies Bartók recorded and transcribed are essential evidence of a crucial and now irrecoverable stage in the history of the cultures he studied. And in the printed literature we find ample evidence of his prowess as a pianist.

It is worth emphasizing at this point that Bartók would have been a notable pianist even had he never written a note of music; unlike Igor Stravinsky, for example, he was not simply a composer who concertized to proselytize for his own works and to pay the bills (though this last factor mattered to Bartók, too, especially during his last years, in America). At various times in his life, one or another of his activities predominated, but the piano had come first: He began lessons with his mother on his fifth birthday and made his first public appearance at eleven. At the Budapest Academy, piano and composition were equally important, and in Paris in 1905, Bartók entered the Prix Rubinstein competitions in both categories; as pianist, he was ranked second to none other than Wilhelm Backhaus, but no composition prize was awarded.

In the years before World War I, Bartók abandoned public performance to pursue his folk-music researches, but he resumed an international career as a pianist in the 1920s, even touring the United States in 1927. When he resigned his teaching position in 1934, after twenty-seven years, it was in order to devote more time to the ethno-musicological studies. In those last, sad years in America, the combination of insufficient public interest and his advancing illnesses put an end to concertizing by early 1943, after which Bartók worried primarily about the future of his wife Ditta, herself a pianist; the Third Piano Concerto was a legacy for her to play.

Testimonials to the qualities of his playing are not hard to find. According to Lajos Hernádi, a Hungarian pianist who studied with Bartók during the 1920s: Whatever he chose to play, every single work sounded genuine under his fingers, from the ideal tempos and phrasings to the most lucid larger outlines of each piece.

... His playing was devoid of all superficial, irrelevant flourish Bartók was not a colorist when he played the piano. Probably this was the only deficiency in his playing, and it appeared only when-very rarely-he played works by composers like Chopin

.... These pieces sounded somewhat strange, as if they had been carved in granite-but they were granite masterpieces all the same.

And an American who studied in Budapest, Wilhelmine Creel Driver, wrote in 1950 to Halsey Stevens, Bartók's biographer: After studying Bach with him and hearing him play the suites and partitas ,all other Bach playing sounds lifeless to me.... He was, of course, more at home with some composers than others. I am sure there has been no greater performer of Scarlatti, Bach, Beethoven, Liszt, and Debussy... . Considering the period during which Bartók was active as a pianist-the first forty years of the century-and his subsequent reputation, we might reasonably expect his playing to be documented extensively in sound as well as in words. Alas, this is not so; his recorded legacy is skimpy indeed. (See accompanying box.) If by some miracle we should turn up a similar cache of recordings by Beethoven, it would contain, say: lots of dances and other short pieces,

------ Bartók would have been a notable pianist even had he never written a note of music. --------

some of them recorded more than once; an early piano sonata; a violin sonata and one of the violin romances; the Kakudu Variations; a live-performance recording of the Archduke Trio in which the players get badly out of synchronization in the last movement; a batch of his and Haydn's folksong arrangements; a few Bach preludes; a short Mozart piece; and violin sonatas by Handel and Mozart.

The comparison is not entirely fair, of course, because the catalogs of the two composers are rather differently balanced-Bartók wrote relatively few large-scaled works for solo piano and very many shorter ones, including those invaluable teaching pieces. Nor does one really regret the extensive recorded selections from the Mikrokosmos, that repository of twentieth-century rhythmic, harmonic, and textural devices; Bartók's resourceful playing is a source of constant wonder, a model of precision and security of rhythmic detail, clarity of contrapuntal lines, and control of dynamic gradations. (Occasionally, here and in other recordings, he varies the written score with octave doublings and other small elaborations.) Still, it is disappointing that we have no recorded evidence of how Bartók played the Etudes, Op. 18, or the piano sonata, or Out of Doors. Not to mention the piano concertos-but then no Bartók concerto was commercially recorded at all during his lifetime. (An air check of the 1939 premiere of the Second Violin Concerto has survived, published on Hungaroton LPX 11573.) Even though Bartók and his wife gave the premiere of the concerto version of the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion with Fritz Reiner and the New York Philharmonic in January 1943, it seems unlikely that any recording was made of this, his last public appearance as a pianist; in accordance with the timid repertory policy that prevailed for the Philharmonic broadcasts in those days, the concerto was omitted from the Sunday afternoon concert, the one that went out over the air.

What does survive of Bartók's playing in large-scale works, however, does come from live performances. Of these, the Library of Congress recital with Joseph Szigeti in 1940 is the most important. Their performance of Beethoven's Kreutzer Sonata is of an extraordinary sweep, intensity, and directness of musical purpose. Comparison with the Szigeti/Arrau performance of a few years later (Vanguard SRV 300/3, electronic stereo) forcefully demonstrates Bartók's mastery of inflection and of dynamic and agogic accenting, sharpening the music's expressive character and variety, and stimulating Szigeti to greater precision as well. The pearly filigree of the piano's right hand in the fourth variation of the slow movement makes one long for a Bartók recording of Beethoven's last piano sonata.

A feature of Bartók's playing that tends to raise modern eyebrows is his frequent arpeggiation, or "rolling," of chords not marked to be played so. This common stylistic feature of turn-of-the-century playing is perfectly acceptable in music whose regular metrical patterns are not thereby significantly obscure--at least, once one has become used to it.

When applied, however, to Bartók's own music, the practice can be more than simply distracting, for his asymmetrical and irregular rhythms need to be sharply and unequivocally articulated; at several points in his Second Sonata and First Rhapsody, the composer's not-together hands distinctly impede musical comprehension--a case where the pianist has not caught up with the implications of the composer's music. In other respects, despite a few live-performance mishaps, these two performances are vivid and compelling; the final page of the sonata is especially eloquent. Only the Debussy sonata is below the highest standard, with some of the "granitic" quality described by Hernádi; to be sure, the restricted frequency range of the recording probably affects the tonal qualities of this piece more severely than the others.

For the Beethoven and Bartók works, this Vanguard set remains the indispensable document of the composer's music-making.

Such an epithet cannot, alas, be applied to the air check of the Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion. Some of the phrasings and articulations are of documentary interest, but this under-rehearsed, ill-coordinated, poorly recorded affair is hardly a fair picture of what Bartók must have intended this masterpiece to sound like. The Columbia studio sessions yield higher quality from lesser music. Contrasts, commissioned by Benny Goodman at the instigation of Szigeti, is a lively divertissement; unfortunately, the current Odyssey edition, in "electronic stereo," does not show either this or one-half of the Mikrokosmos recordings to best advantage. (The studio recording of the First Rhapsody registers the piano more clearly than does the Library of Congress version, but the performance is a shade less spirited.) CBS might fittingly commemorate the centenary with a two-disc set containing good mono dubbings of all its Bartók-plays-Bartók material, banding the Mikrokosmos pieces individually for the convenience of students and, if there is still room, filling it out with Szigeti's postwar recording of Portrait No. 1.

The best news about anniversary reissues, as of this writing, is that EMI has prepared for Hungaroton a tape master of all the solo material that it owns (the 1929 Budapest and 1937 London sessions), plus the 1930 session with Szigeti and a selection from the 1928 folksong recordings. I have been able to hear a sampling of this, and can report that it is much more vivid and open in sound, if also more noisy, than the dubbings of these same recordings on the Peter Bartók LP. The latter, hard to find, will still be valuable for its other con. tents, especially the lucid, subtly accented, pianistically beguiling performances of four Scarlatti sonatas (K. 212 especially entrancing for its featherweight emphasis of the dissonant clashes), and for the free and powerfully cumulative reading of Liszt's "Sursum corda." I hope, however, that we can someday have a new reissue of this material as well; there is more depth of tone in that Liszt, at least on my French Pacific 78 pressing, than is captured on the Bartók LP. As of this writing, it is not known what companies outside of Hungary may pick up the EMI transfers, but they are worth grabbing in whatever form they eventually reach the American market: The Op. 14 Suite and Allegro barbaro are the most important of the shorter works that Bartók recorded, and the folksong arrangements are played and sung with a unique combination of authority and abandon. In the cases where Bartók later remade certain works, the earlier recordings are often more vigorous than the late Continental set-though, at its price and for its_unicae, that, too, is surely worth having.

A legacy that is inadequate in terms of what might have been, Bartók's recordings are nonetheless essential supplements to our image of the man.

The significance and authority of his recordings of his own music go without saying, of course, but his recordings of music by other composers are perhaps the most revelatory of his mind and spirit. This is not entirely paradoxical; playing his own music, he draws on aspects of himself that are already pretty clear in the music to begin with, whereas the music of others summons up differert facets of his personality. Thus it is that, after hearing the entire Bartók discography, my most vivid and telling impressions are of the intellectual and expressive thrust of the Kreutzer Sonata, the sonority of the Liszt piece, the tonal wizardry of the Scarlatti sonatas. HF

------------

Bartók at the Piano: The Recordings

December 1928, Budapest: Hungarian HMV Bartók AND KODÁL1 (arr.): Hungarian Folk-songs (with various singers). No complete reissue' C. 1929: broadcast air check SCARI ATTI, I).: Sonatas, K. 70, 212, 427, 537.

BARTÓK 903 November 1029, Budapest: Hungarian HMV Bartók: Allegro harhuo. Bagatelle, Op. o, No. 2. Burlesque, Op. 8c, No. 2. Ten Easy Pie,,'.: "Evening in the Country"; "Bear Dance." Romanian Dance, Op. 8a, No. I. Suite, Op. 14.

BARTÓK 003 January 7, 1930, London: English Columbia Bartók-SZIGLTI: Hungarian Folk Tunes.

BARTóK-SZÉKELY: Romanian Folk Dances.

(1\ ith loseph Szigeti, violin.) CBS M6X 31513February 5,'1937, London: English Columbia Bartók: Mikrokosmos: Nos. 124, 146.

BARTÓK 903 C. 1937, Budapest (?): Hungarian Patria Bartók: Hungarian Peas alit Songs: Nos. 7-12, 14, 15. Nine Little Pieces: "Air";-Tambourine." Petite Suite: No. o, "Bagpipes." Three Rondos on Folk Tunes: No. 1.

LISZT: Années de pélerinage, Third Year: "Su rsum cerda." 64RTOK 003

c. 1938: broadcast air check Bartók: For Children: Nos. 3, 4, 6, 10,12, 13, 15, 18, 19, 21." Ten Easy Pieces: "Evening in the Country"; "Bear Dance." TURNABOUT TV 4159 (op) April 13,1940, Library of Congress, Washington: recital

BEETHOVEN: Violin Sonata No. 0 (Kreutzer).

DEBUSSY: Violin Sonata. Bartók: Violin Sonata No. 2. Rhapsody No. I. (With Szigeti.) VANGUARD SRV 304/5(e) 1040, New link: Columbia Records BARTOK: Rhapsody No. I (with Szigeti). ColuMBIA ML 2213 (op)

BARToK: Contrast (with Benny Goodman, clarinet, and Szigeti). Oovssi Y 32 16 0220 (e)

BaRTOK: Milrokosmo.: Nos. 94, 100,108-9, 113, 120, 128-9, 131, 133, 138, 140, 142, 148-53. O n ssl Y 32 10 0220 (e)

BARtok: Mikrokosmos.: Nos. 97, 1 14, 7 16, 118, 125-6, 130, 136, 130, 141, 143-4, 147.

COLUMBIA \IL 4419 (op)

c. 1941, New ' York: broadcast air check BARTOK: Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion (with Ditta I'ásztory Bartók, piano; I larry I. Baker and Edward I. Rubsan, percussion). TURNABOUT TV 4150 (op)

c.1043, New 1 ork: Continental Records BARTóK: Bagatelle, Op. 6, No. 2. Three Hungarian Folk Tunes. Improvisations on Hungarian Peaswit Songs, Op. 20: Nos. 1, 2, 6-8. Nine Little Pieces: ''Preludio all'ungherese. " Petite Suite. Three Randoson Folk Tunes: No. I. Mikrokosmos: Nos. 09, 127, 145 (arr. for two pianos; with Dicta I'ásztory Bartók). TURNABOUT THS 65010 (op) out of print (e) electronic stereo A few selections have been included in Hungarian I I collections; a larger sampling is reissued in the anniversary LI' prepared by E\11 for Hungaroton.

Five additional pieces (Nos. 26, 30, 31, 34, 35)on the Vox 78-rpm edition have apparently never appeared on LI'.

------ "Béla Bartók, the mild-mannered Revolutionist," published in New York on the occasion of his first visit, 1927.

Other Tributes

When National Public Radio learned of our plans for this issue, it decided to augment its previously scheduled Bartók programming with an hour-long special titled Collector's Bartók centered around some of the recordings discussed in David Hamilton's article.

The broadcast, featuring Contrasts and excerpts from Mikrokosmos, will originate on the composer's birthday, March 25.

And among the many recordings of Bartók's music scheduled for release this spring, one significant reissue package that won't appear in stores merits special attention: a three-disc (two-cassette) set from Book-of-the-Month Club entitled "Béla Bartók: A Celebration." Pressed by Columbia Special Products, the discs contain not only familiar items from the CBS catalog (Boulez Concerto for Orchestra, Bernstein Music for Strings, Percussion, anti Celesta, Serkin/ Szell First Piano Concerto, Stern/Bernstein Second Violin Concerto), but also the Szigeti/Bartók Library of Congress recordings of the Second Violin Sonata and First Rhapsody; though derived from Vanguard, the historical recordings are here offered in unadorned monaural dubbings. An attractively illustrated booklet includes an introduction by Harold C. Schonberg and exhaustive notes, complete with music examples, by musicologist Benjamin Suchoff, who, in his capacity as trustee of the Bartók estate, supplied many of the photographs in these pages. The album is available only by mail from Book-of-the-Month Records, Camp Hill, Pa. 17012, for $21.95 plus $1.50 for shipping.

HF

++++++++++++++

++++++++++++++

Bartók Recordings Part 1: Early, Piano, and Stage Works

The patchy domestic catalog has its attractions, but the Hungarians get the paprika just right.

by Jeremy Noble

It is a comfortable misconception that the unimpeded interaction of public curiosity and the desire for reasonable profit will automatically secure the dissemination of all the music that is worth hearing. In fact, the larger the public, the more it resists having its preconceptions bruised; the commercial enterprises that service it tend, with rare and precious exceptions, to follow taste rather than to lead it. The result is that even the giants of twentieth-century music would be poorly represented in the record catalogs if it were not for individual enthusiasms: Robert Craft's for Schoenberg and Webern, Goddard Lieberson's and John McClure's for Stravinsky are the most obvious examples. Without the filial commitment of Peter Bartók, the founder of Bartók Records, and the more mixed but no less acceptable fervor of whatever authorities direct the Hungarian record industry, a centenary survey of Bartók on records would be a very patchy affair. Hardly any of the early music or the songs would be available, and only a single version of much of the music he wrote for his own instrument, the piano. So I make no apology for the frequency with which I shall refer, in what follows, to the (nearly) complete edition of Bartók's music on Hungaroton. And since these records are not listed in SCHWANN, let me give straight away the address from which they are available, in case you should have difficulty in persuading your dealer that they exist: Qualiton Records, 39-28 Crescent St., Long Island City, N.Y. 11101.

In the survey that follows I have tried to keep to a generally chronological ground plan, but because a strictly chronological account would involve a lot of repetitive backtracking, I have grouped the works by genre. In this installment you will therefore find 1) the early works (excluding piano and vocal) up to 1912; 2) the solo piano works from Bartók's whole career; and 3) the three stage works composed between 1911 and 1919, which represent a summing up of the past and a turning toward something new. Details of the records referred to are grouped at the end of each section. "Sz." numbers, used in the text only to avoid confusion between works with similar titles, refer to András Szóllósy's work list; though not complete, it is the generally accepted Bartok'Kochel" and is easily accessible in, for example, József Ujfalussy's book on the composer and the New Grove Dictionary.

Early works

The earliest piece currently available on disc is the one completely orchestrated movement of a symphony Bartók wrote during his last year at the Budapest Academy bf Music, 1902-3. The only feature that one might with hindsight recognize as characteristic is the opening ostinato, which later gets ...

This photograph and those that follow were taken by Bartók on his expeditions through Eastern Europe; clearly his interest in folk culture went beyond the musical.

... a brief fugato treatment; otherwise the idiom of the movement sounds more like Dvorák's, though handled with a rather un-Dvorákian economy of thematic material. (The young Bartók evidently knew his Brahms.) Far more specifically Hungarian are the two other pieces on the same disc, Hungaroton SPLX 11517: the symphonic poem Kossuth and the Scherzo for Piano and Orch (Sz. 28). Kossuth shows the young composer attempting (with only partial success) to harness his new enthusiasm for the Strauss of Zarathustra and Heldenleoen to his passionate Hungarian nationalism. Much more successful is the scherzo, which was never performed during Bartók's lifetime, though he gave it the opus number 2; the hypersensitive young composer was so upset by a hostile early rehearsal that he withdrew the score completely. In spite of the title, it is a fully worked-out half-hour work, better integrated than Kossuth and more ambitious than the piano-orchestra version of the solo rhapsody. It has a better claim than the latter to he included in complete sets of the piano concertos, but apart from this disc, with soloist Erzsébet Tusa, the only recording available is Gybrgy Sándor's (Turnabout TV-S 34618): A tougher, more strongly directional performance than Tusa's (and more than two minutes shorter), it is decently recorded, but coupled with a distinctly antique version of Kodály's Háry János Suite.

Another suppressed piece from this period, in which no problems of rival versions arise, is the piano quintet recorded on Hungaroton SLPX 11518.

This time it was not hostility, but limited admiration that led Bartók to withdraw the score; no doubt correctly, he interpreted its enthusiastic reception at a 1921 performance as a backhanded attack on his more recent music. Although a little diffuse, it is a perfectly competent and attractive example of late-Romantic chamber music, rather in Dohnányi's vein.

The Hungarian flavor is much stronger in the Rhapsody (Sz. 27), which proclaims its Lisztian ancestry from the very first bars. Originally written for piano solo (and so recorded by Gabor Gabos on Hungaroton SLPX 1300), it was soon expanded for piano and orchestra and has become more familiar in that guise. Of the three current recordings, I prefer Géza Anda's (coupled with the First Piano Concerto on Privilege 2535 333), which has much better orchestral playing and recording than Sándor's (coupled with a mixed bag of non-Bartókian items on Turnabout TV-S 34130). Tusa underplays the bravura that seems an essential part of the piece in her sensitive performance on Hungaroton SLPX 11480, but the other work here makes more pressing claims. Bartók's Suite No. 1 for orchestra (Sz. 31) is, of all these pieces, the one in which his Hungarianism (still un-purged of the verbunkos tradition) comes closest to that of his friend Kodály: Unusually extrovert and even genial, it could surely be as much of a popular success as Háry János or the Peacock Variations. The recording by the Hungarian State Orchestra under János Ferencsik sounds a little dim in comparison with Antal Dorati's recent version on London CS 7120; but although the Detroit Symphony's winds and brasses are certainly more virtuosic than the Hungarians, its strings are not, a fact that even London's rather over-resonant acoustic cannot obscure. Dorati also seems, on this evidence, no longer to devote as much care to precision of rhythm and dynamics as he once did, but most listeners will probably prefer the more glamorous London sound.

The Second Suite (Sz. 34), though most of it was written in the same year, 1905, is a fascinatingly different piece, withdrawn where the other is outgoing, mordant where it is genial. This may be why we never hear it in the concert hall and why there is no recording apart from Miklós Erdélyi's on SLPX 11355; but it may also be why Bartók came back to it as late as the 1940s, first arranging it for himself and his wife to play on two pianos and then carefully revising the orchestral score. Erdélyi's recording, with the Budapest Symphony Orchestra, is coupled with smaller orchestral pieces of a folky nature, but the suite itself is a substantial work that merits acquaintance. The two-piano version is played by the composer's widow and Mária Comensoli on SLPX 11398; the loss of orchestral color is to some extent offset by the perfect lucidity of the texture (aided by one of the best-balanced recordings of two-piano music that I have heard). The last of the suite's four movements was composed in 1907, the year of the composer's passionate involvement with the violinist Stefi Geyer and of the two works particularly associated with her. As is well known, the so-called Violin Concerto No. 1 (Sz. 36), which Bartók dedicated to her (and which was not heard until after her death in 1958), shares its first movement with the Two Portraits, Op. 5 (Sz. 37); but whereas the second movement of the Portraits is merely an arrangement of one of the piano Bagatelles, Op. 6, a mockingly grotesque treatment of Stefi's theme that in no way balances the lyrical outpouring of the first movement, the second movement of the concerto is a large-scale rondo with many diverse elements, including references to the Andante. Of the available recordings of the concerto, there is not a lot to choose between the performances of Yehudi Menuhin with Dorati (Angel S 36438) and Dénes Kovács with András Kórody (Hungaroton SLPX 11314). Your choice may well be determined by the coupling: Angel offers the viola concerto, Hungaroton only one of the Romanian Dances (Sz. 47a) and the shorter of the two suites from The Wooden Prince, which can surely appeal only to obsessive collectors.

If you have the concerto, you may not want the Two Portraits as well, but they turn up on an attractive disc (SLPX 1302) also containing Erdélyi's performances of the Two Pictures, Op. 10 (Sz. 46), and the Four Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 12 (Sz. 51). The Pictures are not to be confused with the earlier Portraits; those were explicit representations of two aspects of the girl Bartók was, or had been, in love with, while the Pictures (Images in the French title) are imaginary landscapes in the tradition of Debussy, whose music was at this time (1910) having its fullest impact on Bartók's harmony and orchestration. For the Pictures, the choice is once again between Erdélyi, this time with the Budapest Philharmonic, and Dorati's record with the Detroit Symphony already mentioned; the former offers a clearer, if rather distant, sound, and the latter a glamorously wide frequency range and a good deal of unwanted hall resonance.

Any devoted Bartókian who neglected to acquire Eugene Ormandy's RCA recording of the Four Pieces before it was deleted, or to import Eliahu Inbal's Philips version while it was still available, will in any case have to rely on the Erdélyi record for this puzzlingly unsuccessful work. From its title one might imagine that this was Bartók's acknowledgment of recent musical events in Vienna (Schoenberg composed his Five Pieces for Orchestra in 1909, Webern his Six in 1910), but in fact his music has none of their aphoristic intensity. His score is still closer to impressionism than expressionism, and uncharacteristically diffuse.

It seems clear that at this stage of his development Bartók needed the discipline of a dramatic narrative to give his music cohesion and impetus.

[In the lists that follow, performing groups are indicated with appropriate combinations of St (State), P(Philharmonic), R (Radio), S (Symphony), O (Orchestra), and Ch (Chorus). Where a set includes more than one disc, the number is given parenthetically following the record number.]

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11517-Scherzo (from Symphony in E flat); Kossuth; Scherzo for Piano and Orchestra (Sz. 28) (with Tusa). Budapest SO, Lehel.

TURNABOUT TV-S 34618-Scherzo for Piano and Orchestra (Sz. 28). G. Sándor; Luxembourg RO, Cao. (Also KODÁLY: Háry János: Suite. London PO, Solti.)

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11518-Piano Quintet. Szabó; Tátrai Quartet.

DG PRIVILEGE 2535 333-Piano Concerto No. 1 (Sz. 83); Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra (Sz. 27). Anda; Berlin RSO, Fricsay.

TURNABOUT TV-S 34130-Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra (Sz. 27). G. Sándor; Southwest German RSO, Reinhardt. (Also works by Honegger, Jana ek, Stravinsky.)

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11480-Rhapsody for Piano and Orchestra (Sz. 27). Tusa; Budapest SO, Németh. Suite No. 1 (Sz. 31). Hungarian StO, Ferencsik.

LONDON CS 7120-Suite No. 1 (Sz. 31); Two Pictures (Sz. 46). Detroit SO, Dorati.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11355-Suite No. 2 (Sz. 34); Romanian Folk Dances (Sz. 68); Transylvanian Dances (Sz. 96); Hungarian Sketches (Sz. 97). Budapest SO, Erdélyi.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11398-Suite for Two Pianos (Sz. 115a). Pásztory Bartók, Comensoli. Concerto for Two Pianos, Percussion, and Orchestra (Sz. 115). Pásztory Bartók, Tusa; Budapest SO, J. Sándor.

ANGEL S 36438-Violin Concerto No. 1 (Sz. 36); Viola Concerto (Sz. 120). Menuhin; New Philharmonia O, Dorati.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11314-Violin Concerto No. I (Sz. 36) (with Kovács); Romanian Dance (Sz. 47a); The Wooden Prince (Sz. 60): Suite. Budapest PO, Kórody.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 1302-Two Portraits (Sz. 37) (with L. Szücs); Two Pictures (Sz. 46); Four Pieces for Orchestra (Sz. 51). Budapest PO, Erdélyi.

The solo piano works

The piano was Bartók's instrument in a more complete sense than it was for any major twentieth-century composer apart from Prokofiev. Plenty of other composers have been fine pianists, of course, but few have been so thoroughly involved with the whole tradition of pianism, both as a virtuoso mode of self-expression and as a body of pedagogical method. To Bartók both aspects were important from the start. The fact that he possessed a formidable technique did not alienate him from beginners' problems; if anything it seems to have made him more conscious of the need to provide the young pianist with purely musical challenges. And he himself would often include groups of these relatively simple pieces in his own recitals, as if to proclaim that they were as intrinsically musical as his more elaborate works. So I think that it is right, indeed inevitable, that both of the "complete" recordings of Bartók's piano music-Vox's (Sándor) and Hungaroton's (various pianists)-have included just about everything.

Hungaroton starts its series with a disc (SLPX 1300) on which Gabos plays two works not to be found in the Sándor set: the Four Pieces of 1903 (including an impressive study for the left hand) and the original solo version of the Rhapsody, Op. 1 (Sz. 26), which 1 am inclined to prefer to its better-known expanded form with orchestra.

Gabos has no rivals in these two works, but comparisons arise with the works on the second record in the Hungaroton series, particularly with the Op. 6 Bagatelles, in which we find Bartók exploring in miniature some of the new o f ' 'y, á 440, technical ideas that his study of folksong was beginning to give him. Of the four available versions, Robert Silverman's (Orion ORS 74152) is scrupulously thought-out but a little lacking in spontaneity; there are also some pressing-defects can my copy. Tibor Kozma, on a mono record (Bartok 918), is crisp, serious, and lather lacking in charm.

Kornél Zempléni (Hungaroton SLPX 1299) gives the gentlest and in some ways the most attractive performance, though his disc, one of the earliest of the Hungaroton series, has some pre-echo.

Sándor, in Vol. 3 of the Vox series (SVBX 542.5/7), shows at once the strengths and weaknesses that characterize all his performances to a greater or lesser extent: a constant determination to project the music, combined with a certain waywardness about details of tempo and dynamics. It is true that Bartók himself said many of the pieces in Mikrokosmos could be taken at different speeds (though his own recordings stick pretty closely to the published markings). But I cannot believe that a composer who marked his tempo modifications so carefully really wanted much application of additional rubato.

Nor can I believe that Sándor's constant insistence on turning piano into at least mezzo forte (particularly when "bringing out the melody") is what Bartok had in mind. To me the effect is overemphatic, utterly different from the aristocratic reticence and control of Bartók's own playing. Nor can I accept it as necessarily Hungarian, since none of the pianists in the Hungaroton series seems to indulge in it. Is this not a case of the cook in exile developing a heavier hand with the paprika than he would have been encouraged to use at home? I don't know, and I don't wish to imply that the three-volume Vox set is not a remarkable achievement and good value for its very reasonable price. But I do think that the application of a single, strongly individual style to such a large body of music becomes wearing after a while-and also misleading, if it is the only one available.

For those libraries that can afford it, I would think that the complete Hungaroton series (I shall continue to discuss the individual records below) would be at the least a valuable corrective, while private buyers looking only for a particular piece might do well to consider such alternatives as exist.

Loránt Szücs, who plays four of the sets from 1908-10 on SLPX 11335, seems if anything to exaggerate the reticence; Sándor certainly projects the impassioned rhetoric of the Two Elegies (Sz. 41) more convincingly, though he again seems overemphatic in the more modest Sketches (Sz. 44). On the other hand, Zempléni's unaffected simplicity of approach pays off in For Children (Hungaroton SLPX 11394/5), where Sándor seems too determined to put it across.

So far in comparing the two series it has been possible to balance the good qualities of each against the other, preference being partly a matter of taste; but with young Dersó Ránki's disc (SLPX 11336), we come to a pianist who combines all of Sándor's vividness of response with a much more refined sense of detail. This emerges from a comparison of their accounts of the Three Burlesques (Sz. 47), of the Allegro barbaro, of the Suite, Op. 14 (Sz. 62), and even of the folky little Sonatina (Sz. 55), though Ránki takes its middle movement too slowly, I think. This record, which in conformity with the overall plan of the Hungaroton series also contains a few less important pieces, is one that I can recommend wholeheartedly as a model of elegant and vital playing. (Gary Graff-man, incidentally, gives a nice, firm performance of the suite on Odyssey Y 35203, but the sound is a little archaic by present standards, and I could not recommend the disc for this piece.) For its next record (SLPX 11337), Hungaroton returns to Gabos; fortunately, on this disc he plays with more personality than he did on his earlier one, since it contains two of Bartók's most important piano works, the fiendishly demanding Studies, Op. 18 (the pianistic equivalent of The Miraculous Mandarin), and the closely related but much simpler Improvisations, Op. 20, with their climactic elegy for Debussy.

Cabos may not bring off the hair-raising difficulties of the studies with quite so much panache as Paul Jacobs on a fascinating disc devoted to twentieth-century studies (Nonesuch H 71334), but the details are firmer, and he certainly outclasses both Sándor (who makes unusually heavy weather of these pieces) and Noel Lee, whose otherwise attractive record (Nonesuch H 71175), also containing the suite, the Sonata (Sz. 80), and Out of Doors, suffers from a rather toppy, disembodied sound. The Improvisations show that Cabos can combine sensibility with strength, and in the piano transcription of the 1923 Dance Suite he does everything possible by means of phrasing and touch to make up for the loss of the original's orchestral colors. (Silverman's version is more than respectable but not in this class.) For her only solo disc in the Hungaroton series (SLPX 11338), Tusa is allotted two of the big works from Bartók's hard-edged postwar period, the sonata and the suite Out of Doors, both composed in 1926, as well as some minor ones. The first bars of the sonata dispel any doubts that she carries enough weight for them: Her phrasing is marvelously vivid in both strenuous and reflective music-a function of the musical thought rather than an applied stylishness. Apart from Sándor (dashing but not always precise) and Lee (put out of court by that flimsy sound, though his slow movement is more nearly in tempo than Tusa's), there is a good recording of the sonata by Gabriel Chodos on Orion ORS 73122; its only drawback is the now familiar reluctance to come down to a real piano, so that the tension is too unremitting. This seems a common fault in Bartók performance (spread by bad example?): It also afflicts parts of Stephen Bishop-Kovacevich's otherwise impressive record (Philips 6500 013) containing Out of Doors and the sonatina as well as the final book of Mikrokosmos, the set of graded piano pieces on which Bartók worked on and off for almost the last twenty years of his life. There are one or two points in Bishop-Kovacevich's playd

!ing of Out of Doors where he scores over Tusa (a stronger left hand in the galloping last movement, for one), but he is hampered by a clangy, reverberant piano sourd. No one is as good as Tusa, in-c identally, at bringing out the one important note from each tone-cluster in "The Night's Music" without ever infringing its overall pianissimo-a feat no less remarkable for being unspectacular.

As for a complete Mikrokosmos, the choice lies once more between the extrovert Sándor on Vox (the whole of Vol. 1) and the much more intimate playing of Szücs (Books I-IV) and Zempléni (Books V-VI) on Hungaroton SLPX 11405/7; though Ranki's recording on Telefunken 36.35369 failed to reach me, I would have no hesitation in recommending it on the strength of his splendid record mentioned above. Finally, on SLPX 11320, Hungaroton gives us the two-piano transcriptions Bartók made to play in recital with his wife, Ditta Pásztory Bartók; here she plays them with Tusa. The two pianos are not balanced quite as well as in the recording of the Second Suite already mentioned, but the interpretation carries a special authority.

Vox SVBX 5425 (3)-Mikrokosmos (Sz. 107). G. Sándor. Vox SVBX 5426 (3)For Children (Sz. 42); Allegro harharo (Sz. 49); Romanian Folk Dances (6) (Sz. 56); Romanian Christmas Carols (20)(Sz. 57); Fifteen Hungarian Peasant Songs (Sz. 71); Sonata (Sz. 80); Out of Doors (Sz. 81); Three Rondos on Faik Tunes (5z. 84); Petite Suite (Sz. 105); Sonata for Two Pianos and Percussion (Sz. 110) (with Reinhardt). G. S.indor. I+9 (---) i Vox SVBX 5427 (3)Three Hungarian Folksongs from the Csik District (Sz. 35a); Fourteen Bagatelles (Sz. 38); Ten Easy Pieces (Sz. 39); Two Elegies (Sz. 41); Seven Sketches (Sz. 44); Four Dirges (Sz. 45), Three Burlesques (Sz. 47); Sonatina (Sz. 55); Suite (Sz. 62); Three Hungarian Folk Tunes (Sz. 66); Three Studies (Sz. 72); Improvisations on Hungarian Peasant Songs (8) (Sz. 74); Nine Little Pieces (Sz. 82). G. Sándor HUNGAROTON SLPX 1300-Four Pieces; Rhapsody for Piano (Sz. 26). Gabos.

ORION ORS 74152-Fourteen Bagatelles (Sz. 38); Dance Suite (Sz. 77). Silverman.

BARTÓK 918-Fourteen Bagatelles (Sz. 38); Romanian Folk Dances (6) (Sz. 56); Romanian Christmas Carols (20) (Sz. 57). Kozma.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 1299-Ten Easy Pieces (Sz. 39); Three Hungarian Falksongstrarn the Csik District (Sz. 35a); Fourteen Bagatelles (Sz. 38). Zempléni.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11335-Two Elegies (Sz. 41); Two Romanian Dances (Sz. 43); Seven Sketches (Sz. 44); Four Dirges (Sz. 45). L. Szücs.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11394/5 (2)-For Children (Sz. 42). Zempléni.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11336-Three Burlesques (Sz. 47); Allegro barbaro (Sz. 49); The First Terms at the Piano (Sz. 53); Sonatina (Sz. 55); Six Romanian Folk Dances (Sz. 56); Romanian Christmas Carols (20) (Sz.57); Suite (Sz. 62); Three Hungarian Folk Tunes (Sz. 66). Ránki.

ODYSSEY Y 35203-Suite (Sz. 62). Graffman.(Also works by Prokofiev, Lees ) HUNGAROTON SLPX 11337-Fifteen Hungarian Peasant Songs (Sz. 71); Three Rondos on Folk Tunes (Sz. 84); Three Studies (Sz. 72); Improvisations on Hungarian Peasant Songs (8) (Sz. 74); Dance Suite (Sz. 77). Cabos.

Nonesuch H 71334-Three Studies (Sz. 72). Ja-. cobs. (Also works by Busoni, Messiaen, Stravinsky.) NONESUCH H 71 175-Three Studies (Sz. 72); Out of Doors (Sz. 8I ); Suite (Sz. 02); Sonata (Sz. 80). Lee.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11338-Sonata (Sz. 8O); Nine Little Pieces (Sz. 82); Out of Doors (Sz. 81); Petite Suite (Sz. 105). Tusa.ORION ORS 73122-Sonata (Sz. 80). Chodos. (Also works by Bloch, Franck.) PHILIPS 6500013-Mikrokosrnos (Sz. 107), Book VI; Out of Doors (Sz. 81); Sonatina (Sz. 55). Bishop-Kovacevich.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11405/7 (3)-Mikrokosrrros (Sz. 107). L. Szücs (Books I-IV), Zempléni (Books V-VI). TELEFUNKEN 36.35369 (3)-Mikrokos mas (Sz. 107). R,inki.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11320-Mikrokosmos (Sz. 107): Seven Pieces for Two Pianos (arr. Bartók) (Sz. 108). PSsztory Bartók, Tusa. Forty-four Duos for Two Violins (Sz. 98). Wilkomirska, M. Szücs.

Stage works Like many other composers, Bartók seems to have reached a stylistic crisis about the time of the First World War-partly a matter of organizing large-scale works with a musical syntax that appeared to have been stretched to the breaking point, partly a matter of reconciling the exalted late-Romantic concept of the artist as Nietzschean superman with a world in which individuality looked like being swamped forever by mass movements and mass slaughter.

Certainly the three stage works-the opera Bluebeard's Castle (191 1) and the ballets The Wooden Prince (1914-16) and The Miraculous Mandarin (1913-19)-all proclaim the perfervid individualism of Bartók's attitudes at this time. For him quite as much as for Wagner a couple of generations earlier, the central fact was the genius' (i.e., his own) relationship to the world and, more particularly, the sexual aspect of that relationship, about which each of these works attempts to make a large general statement. Bluebeard demonstrates the self-destruction inherent in the relationship between a creative man and even the most loving of women.

(The published letters to Stefi Geyer come to mind.) The Wooden Prince purports to give the same kind of relationship a happy ending, with each of the parties purged by experience. With the Mandarin, the shadows fall once more: The exotic and elemental stranger is drawn to the sordid everyday world by his sexual needs; only in satisfying them can he find the peace of extinction.

Whatever we may think of the message of each of these works, they clearly meant enough to Bartók at the time to stimulate him to the largest, most ambitious scores he had yet composed, scores that draw on the whole of his musical experience. The intensity of feeling that underlies Bluebeard is such that for the whole course of the work he achieves a completely individual and convincing amalgam of the three main influences on his music thus far: Strauss, Debussy, and Hungarian folksong. In The Wooden Prince, probably because the relatively banal scenario did not echo his deepest psychological experience, that stylistic amalgam comes apart, like curdling mayonnaise. In the Mandarin, a new synthesis is achieved, but on a much more individual basis, with a new rhythmic and harmonic vocabulary from which definable forebears have almost disappeared. With these three works, spanning less than a decade, Bartók seems to have purged himself of the whole Romantic world view. Never again did he feel tempted to exalt subjective experience in this explicit way, except once, and much more obliquely, in the elusive Cantata profana of 1930. Interestingly enough, these three scores, crucial as they are to any real understanding of Bartók's development, remained almost unknown until a generation ago. He himself prepared shortened versions (the so-called suites) from the two ballet scores, but they met with little success in the concert hall. Only with the advent of the LP did the complete scores become more familiar, and if the number of available recordings is any indication, they must now be said to have arrived.

Not surprisingly, it is Bluebeard, with its opportunities for orchestral display and nuanced psychological portrayal, that has made the most headway.

Currently there are at least six versions available; at the time of writing I have not yet heard a seventh, conducted by Str Georg Solti (London OSA 1174, January). What is more, none of them is without good qualities, and one can choose only by pinpointing individual failings that might be perfectly tolerable in a live performance. Thus Dorati's newly reissued version, as Paul Henry Lang remarked in reviewing it last August, is marred by Olga Szónyi's shrill and unsteady performance as Judith. Since this version is obtainable only as part of a three-disc set (Mercury SRI 3-77012) containing all three stage works, it may be as well to say straight away that Dorati's accounts of the other two scores, and particularly of the Mandarin, are among the very best. Ferencsik's performance on Hungaroton SLPX 11486 is sung by two Hungarian singers of a younger generation; clearly they have grown up with the work, and familiarity has begun to breed sloppiness, an imprecision in rhythms, tempos, even notes that represents, I'm afraid, the digestion of a finely chiseled masterpiece into a repertory work. The very full (even by Hungaroton's generous standards) annotations, though, contain a lucid account by Gyorgy Kroó of the work's psychological meaning-required reading for singers and producers, I think. The new version by Dietrich Fischer-Dieskau and his wife, Julia Varady, on Deutsche Grammophon 2531 172 (August) is inconsistent in style, with Fischer-Dieskau himself turning in an intelligent but excessively mannered performance that somehow misses real dignity. The two most powerful versions are those of István Kertész (London OSA 1153) and Pierre Boulez (CBS M 34217); of these I marginally prefer the latter, which I reviewed in some detail in February 1977, above all for the thrillingly intense singing of Tatiana Troyanos. But like Lang, I find that the elderly recording under Walter Susskind (Bartók 310/ 11), with Endre Koreh as an unforgettably majestic Bluebeard, still says some things better than any more recent version; it will be interesting to see what it sounds like if it is ever transferred onto a single stereo disc, since on two monos it is hardly competitive.

The Wooden Prince is also available complete in two first-rate versions, of which Dorati's (already mentioned) seems to me the more idiomatic and Boulez' (CBS M 34514) slightly the better recorded. In any case, both meet the virtuoso demands of the score more completely than the Hungaroton version (SLPX 11403) under Kórody. Although I do not really believe that such weaknesses as The Wooden Prince has are mended simply by truncating it, Stanislaw Skrowaczewski's coupling of the r suites from this work and The Miraculous Mandarin on Candide QCE 31097 is worth investigating if economy is vital.

If you can come to terms with the Mandarin at all, though, it seems to me that you will want the complete score; the so-called suite lops off the entire final section, containing the Mandarin's grisly Liebestod, a passage that clearly stimulated the deepest reaches of Bartók's imagination. Once more Boulez (CBS M 31368) and Dorati are close rivals, outclassing the performance on Hungaroton SLPX 11319. This time my preference would go to Dorati, who sustains the work's ferocity better and keeps its impetus even through that disintegrative final section. As a footnote, I should mention that Solti's recording of the suite (London CS 6783) is just about unbeatable as far as it goes, with every lurid gesture honed to a razor's edge. But I shall come back to that . record when I consider the various versions of the wonderfully contrasted work with which it is coupled, the Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta.

MERCURY SRI 3-77012 (3)-Bhiebeard's Castle (Sz. 48) (with Szónyi, Székely); The Wooden Prince (Sz. 60). London SO, Dorati. The Miraculous Mandarin (Sz. 73)

BBC SO&Ch, Dorati. Dance Suite (Sz. 77). Philharmonia Hungarica, Dorati.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11486-Bluebeard's Castle (Sz. 48). Kasza, Melis; Budapest PO, Ferencsik.

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPIION 2531 172-Bluebeard s Castle (Sz. 48). Varady, FischerDieskau; Bavarian StO, Sawallisch.

LONDON OSA 1158-Bluebeard's Castle (Sz. 48). Ludwig, Berry; London SO, Kertész.

CBS M 34217-Bluebeard's Castle (Sz. 48). Troyanos, Nimsgern; BBC SO, Boulez.

BARTOK 310/ 11 (2)-Bluebeard's Castle (Sz. 48). Hellwig, Koreh; London New SO, Susskind.

CBS M 34514-The Wooden Prince (Sz. 60). New York P, Boulez.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11403-The Wooden Prince (Sz. 60). Budapest PO, Kórody.

CANDIDE QCE 31097The Wooden Prince (Sz. 60): Suite. The Miraculous Mandarin (Sz. 73): Suite. Minnesota O, Skrowaczewski.

CBS M 31368-The Miraculous Mandarin (Sz. 73) (with Schola Cantorum of New York); Dance Suite (Sz. 77). New York P, Boulez.

HUNGAROTON SLPX 11319-The Miraculous Mandarin (Sz. 73); Dance Suite (Sz. 77); Hungarian Peasant Songs (Sz. 100). Budapest PO, J. Sándor.

LONDON CS 6783-The Miraculous Mandarin (Sz. 73): Suite. Music for Strings, Percussion, and Celesta (Sz. 106). London SO, Solti. NR

-----------------

(High Fidelity, Mar 1981)

Also see: