Hitachi's Thoroughgoing Tape Adjustment

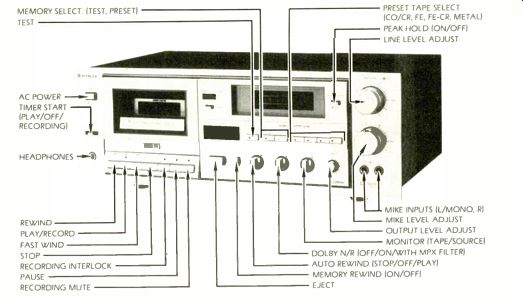

Hitachi D-3300M cassette deck, in metal enclosure with simulated wood-grain finish. Dimensions: 17 1/4 by 6 inches (front panel), 10 inches deep plus clearance for controls and connections. Price: $700; optional RB-100 remote control, $40. Warranty: "limited," three years parts and labor. Manufacturer: Hitachi, Ltd., Japan; U.S. distributor: Hitachi Sales Corp. of America, 401 W. Artesia Blvd., Compton, Calif. 90220.

We continue to marvel at self-adjusting decks, though the microprocessor technology that makes them possible is not abstruse and, at least at the upper price levels, the inclusion of some sort of automated tape matching is not all that uncommon. When you start recording on the D-3300M and press TEST START, the AIRS (Automatic Tape Response System) panel comes to life: The 1-kHz LED comes on, followed by that for 7 kHz, alternating with that for 15 kHz until the microprocessor is satisfied with the flatness and Dolby calibration of its work. Then the deck stops, and we sit bemused. In the face of so pre-emptive a feature, it's hard to focus on all the others in this very enjoyable deck.

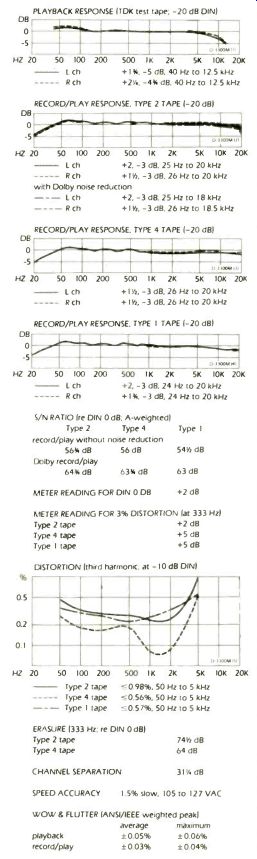

But let's start with the transport itself. As the accompanying data show, speed is totally unaffected by line voltage but notably on the slow side. Most decks run a bit fast (improving high-frequency response ever so slightly), and we generally consider anything within ± 1% as above reproach for consumer purposes. Thus, a figure of 1.5% slow is surprising. It might even prove a subject of complaint if you were to play on it tapes made on a deck that runs 1.5% fast, or vice versa, because reproduced pitch would then be about a quarter-tone off the mark. (That is, middle C would reproduce about half way between C and either B natural or C sharp, depending on which machine was used for recording and which for playback.) This still would not be a major consideration in most consumer applications (remember that, when you record and play on the same machine, pitch remains exact), and the speed behavior of the transport is otherwise excellent. Notice, in particular, the wow figures; those for record/play are lower than those for playback, meaning that there is less wow in the deck than in the test tape, and are in the champion class--never bettered and seldom equaled since we began using the ANSI measurement spec two years ago. The credit presumably is due to Hitachi's brushless, coreless, slotless capstan-motor design. This, we think, is more important than absolute speed.

There are some nice twists to the transport controls, whose "logic" permits ad lib hopping from one function to another without passing through STOP or collecting damaged tapes. If you simultaneously press the recording interlock and the PAUSE, the PLAY button automatically lights as well; you are ready to go when you release the PAUSE (which actually requires you to press PLAY in this deck). Unfortunately, the tiny LEDs that indicate current operation mode are omitted from the fast-wind buttons; since it's relatively difficult to see what's going on in the cassette compartment, we found ourselves squinting at the deck trying to determine whether a fast-wind mode had begun or ended. On the other side of the ledger, the PAUSE makes exceptionally transient-free "edits" on the tape-no pops, no ticks, no burbles, so to speak-and leaves only a tiny (approximately 1/4 second) hiatus in any sound continuing through the pause.

The metering scheme is pleasant, though it, too, struck us as a good idea that could have been better. The pattern is clear and the calibration adequate, extending from-20 to +8 aB with 1-dB increments between-3 and +3 dB. And Hitachi gives you a choice of peak or peak-holy modes, with quick response and no overshoot. But the peak hold does not decay after a few seconds to let you know what range the sound has got into in the meantime (an arguable benefit since it will "remember" a maximum even if you're out of the room). And it doesn't operate at all below-1 dB, meaning that, if you don't have the level set near the correct spot to begin with, the peak hold won't help you get it better.

Passing over the many other well-recognized features cataloged in the picture, that brings us back to the piece de resistance: the automatic tape matching.

As the presence of three test frequencies should suggest, it does considerably more than most user-adjusted bias/sensitivity controls You begin the process by choosing one of four tape groups (corresponding to our Types 1-4), which determines the microprocessor's starting point and methodology. If, for any reason (for example, because you've pressed the wrong tape-type button), the microprocessor can't successfully complete its adjustments, it will stop the transport and flash the TEST button's LED to signal the error. But if all goes well, the microprocessor adjusts for tape sensitivity (to the nearest 1/2 dB), determines bias response, and sets bias from it according to a formula for the tape type, then goes for flattest response by trimming recording equalization in two bands. The methodology is a close approximation of what a technician would do on the test bench and makes most user controls seem unconscionably crude by comparison.

The results, as you might expect, were excellent replication, using the monitor switch to A/B playback with source, on any branded tape we threw at the deck. On the Diversified Science Laboratories test bench, the microprocessor seemed to have some doubt about how to set the deck for metal tapes, but we consistently got excellent results with them in listening tests. All this makes it relatively unimportant which brands are used for measurements. We weren't surprised that Hitachi suggested tapes from its Maxell subsidiary_ UDXL-I for the Type 1 ferric, UDXL-II for the Type 2 ferri-cobalt, and MX for the Type 4 metal. Actually, Hitachi offers its own branded product in all three categories and adopts its own nomenclature, which is similar but not identical ( Hitachi's UD-EX appears to be interchangeable with Maxell's UDXL-II, for example), on the faceplate. And the manual, which is otherwise distinctly above average and appears to be produced expressly for the U.S. market, compounds the difficulty by using the Maxell nomenclature as it existed (before the recent introduction of XL-IS and XL-IIS) in Japan. These contributions to confusion are both reprehensible and unnecessary; Hitachi doubtless has its own reasons for visiting them on its customers, but the habit is un-endearing.

The deck itself, however, is generally very endearing. For example, when you have run a tape through the test procedure, you then have the option of either using the resulting settings just for that tape or of putting them into the permanent memory for that particular tape type. (Incidentally, there is even a silver oxide battery to retain the memory when the power cord is disconnected and a front-panel LED to tell you when the battery needs replacement.) So you can record optimally on an "oddball" formulation that doesn't match the memorized information and do so without disturbing that information. Very neat.

Our overview of the D-3300M sees it as a beautifully conceived deck in most respects, with a few small but maddening exceptions. The extreme right end of the front panel sums up what we mean. It holds two mike inputs; if you use the left one only, you automatically get mono. Bravo! Then come the mike and line recording level controls, each with separate elements for the two channels, for excellent flexibility in setting, mixing, and balancing levels. Again, bravo! Yet these controls have no connection whatever between their left and right elements. That makes it very easy to correct channel balances, but also very easy to get them wrong and almost impossible to execute synchronous level changes (fades) in both channels without intense concentration.

--------

A Quick Guide to Tape Types

Our classifications, Types 0 through 4, are based largely on those embodied in the measurement standards now in the process of ratification by the International Electrotechnical Commission.

The higher the type number, the higher the tape price generally is in any given brand. Similarly, the higher type numbers imply superior performance, though-depending in part on the deck in which the tape is used-they do not guarantee it.

Type 0 tapes represent "ground zero" in that they follow the original Philips-based DIN spec. They are ferric tapes, called LN (low-noise) by some manufacturers, requiring minimum (nominal 100%) bias and the original, "standard" 120-microsecond playback equalization. Though they include the "garden variety" formulations, the best are capable of excellent performance at moderate cost in decks that are well matched to them.

Type 1 (IEC Type I) tapes are ferrics requiring the same 120-microsecond playback EQ but somewhat higher bias.

They sometimes are styled LH (low noise, high output) formulations or "premium ferrics." Type 2 (IEC Type II) tapes are intended for use with 70-microsecond playback EQ and higher recording bias still (nominal 150%). The first formulations of this sort used chromium dioxide; today they also include chrome-compatible coatings such as the ferri-cobalts.

Type 3 (IEC Type Ill) tapes are dual-layered ferri-chromes, implying the 70-microsecond ("chrome") playback EQ. Approaches to their biasing and recording EQ vary somewhat from one deck manufacturer to another.

Type 4 (IEC Type IV) are the metal-particle, or "alloy" tapes, requiring the highest bias of all and retaining the 70-microsecond EQ of Type 2.

-----

Report Policy: Equipment reports are based on laboratory measurements and controlled listening tests. Unless otherwise noted, test data and measurements are obtained by CBS Technology Center, a division of Columbia Broadcasting System, Inc., and Diversified Science Laboratories. The choice of equipment to be tested rests with the editors of HIGH FIDELITY. Samples normally are supplied on loan from the manufacturer. Manufacturers are not permitted to read reports in advance of publication, and no report, or portion thereof, may be reproduced for any purpose or in any form without written permission of the publisher. All reports should be construed as applying to the specific samples tested; HIGH FIDELITY, CBS Technology Center, and Diversified Science Laboratories assume no responsibility for product performance or quality.

-----

[Preparation supervised by Robert Long, Peter Dobbin, and Edward J. Foster. Laboratory data (unless otherwise noted) supplied by CBS Technology Center or Diversified Science Laboratories.]

(High Fidelity, Mar 1981)

Also see:

Audio Research SP-6 preamplifier

Equipment Reports (Apr. 1980): Vector Research VRX-9000 receiver; Dynavector 20A Type 2 cartridge; Dynaco A-250 speaker; Onkyo TA-2080 cassette deck; Koss HV/X headphones; ADC Sound Shaper Three equalizer