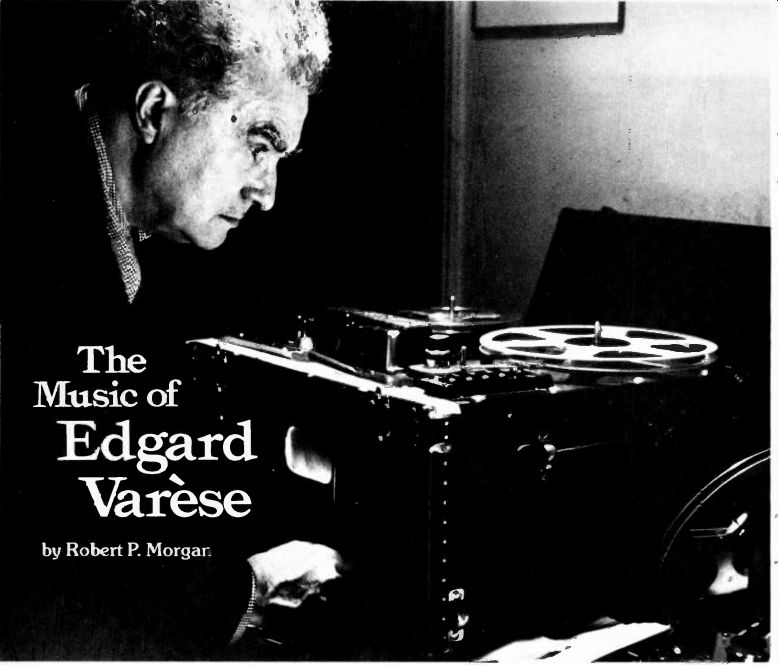

Varese in New York, by Louise Varese; The Music of Edgard Varese, by Robert P. Morgan

-------------

Varese in New York: From Ecuatorial to Integrales

by Louise Varese

----------- Edgard and Louise Varese in the garden of their house in New York

City in the Thirties.

--------------

In 1933, after five years in Paris, Edgard Varese returned to the U.S., his adopted country. In an excerpt adapted from the as yet unpublished Volume II of her memoir, Varese: A Looking Glass Diary, his widow tells of the consequent developments in his composing career.

As WE STEAMED UP the bay on October 14,1933, Varese, standing on the forward deck, waved his hand toward the skyscrapers sharply silhouetted against the clear as it used to be) blue sky and once more took possession: "My New York," he said.

Paraphrasing Socrates, Varese used to say, "Fields and trees teach me nothing, but the sounds of New York City do," for his constant concern was sound, not, like Socrates', people. He was elated to be back in "his" city; it acted as both balm and stimulant. "The air of New York," he told everybody, "is the elixir vitae." Our first night we went to Romany Marie's for dinner. The minute someone caught sight of him in the doorway, there were cries of "It's Varese! Varese is back! Varese! Varese!" Of the old friends who crowded around him, I remember John Sloan, the painter of the so-called Ashcan School, with his little Dolly, sculptor William Zorach, poet Alfred Kreymborg, and-almost hidden by Arctic explorer Vilhjalmur Stefansson-Frederick Kiesler, architect of "endlessness." But from the noise of voices echoing in the ears of memory, there must have been many more.

And now at last Varese would meet Martha Graham, a meeting he had been anticipating ever since 1929, when I had brought back to Paris from a brief visit to New York my enthusiastic impression of the young dancer and when Carlos Salzedo had written that she was "even greater than Nijinsky." It will be remembered that Salzedo, composer, harpist, and all-around musician, was cofounder with Varese of the International Com posers Guild in 1921, the first society for modern music in New York. It was Salzedo's idea that Martha Graham should dance to Varese's music, and during that 1929 trip he arranged for her to see me about such an eventuality.

Varese had a definite plan for two programs in the spring: a concert of music by members of the Pan-American Association of Composers and a Graham recital with interludes of works by the Pan-Americans. The three PAAC members then in New York, Henry Cowell, Wallingford Riegger, and Adolph Weiss, were enthusiastic. Cowell immediately went off to talk to Charles Ives, who was not only an honorary member of the society, but its good angel as well. That was before he had been discovered by the great music world, which is now doing him belated justice. He had become interested in the PAAC through his friend Cowell and had more than once saved it from dissolution from lack of funds. He had twice sponsored concerts abroad led by the group's official conductor, Ni colas Slonimsky, to educate Europe as to what the avant-garde composers of the Americas were doing. I remember the amazement and admiration among the musicians and critics of Paris as they heard for the first time Ives's many anticipatory modern inventions in his scores.

Varese promised a new work for the first con cert, one he had begun in Paris and christened Ecuatorial--or Equatorial. (He wavered between the two until finally settling on the Spanish spelling.) The text that inspired it (if I may be permitted so weary a word) is a Maya-Quiche invocation he came across in Leyendes de Guatemala by his friend Miguel Angel Asturias, who was to be awarded the Nobel Prize in 1967 for his stark and lyrical books, all impregnated with the "greenfire" of his country and his hatred of dictators.

As Ecuatorial called for electronic instruments, Varese went to see Leon Theremin. The young Russian electrical engineer/inventor was one of the three most important inventors of sound-producing instruments, along with Maurice Martenot (ondes martenot) and Rene Bertrand (Dynaphone). Theremin had built three different models, all on the same principle-fingerboard control, keyboard control, and space control.

Since 1930 he had been giving concerts with the ...

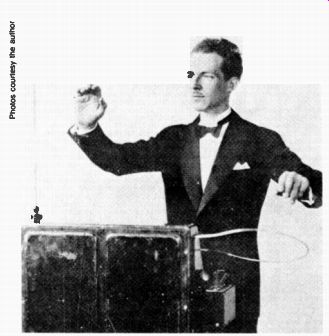

------- Leon Theremin manipulates his invention at a concert of "ether-wave

and electrical music" in the early Thirties. In 1933 Varese worked with

the inventor at his New York studio.

... mystifying third model, which Varese described for one of his lecture audiences: "The space-control type was sensationally advertised as 'music out of the air' because the player stood in front of the instrument producing music without any visible contact with it-magically as it seemed-waving his hands in the air. Technically what happens is that conditions in an electromagnetic area around the instrument are altered by introducing into this area an electrical conductor (the human body). This functions as a regular capacitance in a portion of the circuit and so achieves change in pitch, timbre, and volume. As the right hand approaches the vertical rod of metal, the pitch of tone becomes higher, and as the hand draws away, it becomes lower. Similarly, the intensity of tone is regulated by approaching or withdrawing the left hand from a metal ring on the left of the apparatus." Coming away from one of those recitals of "ether-wave music" (to quote the program), Varese vehemently protested, "What a misuse of means!" For out of the air came music by eighteenth- and nineteenth-century masters that some how sounded unfamiliar--"impostors," Varese said. Thankful though he was for these first devices that would liberate music from the tempered system, he condemned the use that was made of them. He once wrote, "So far, they have been stupidly exploited by ineffectually imitating existing instruments. Their true function is not to re produce sounds, but to produce sounds that man power instruments are incapable of producing.

They have been used as stunts instead of composers' tools." What with the joy of working with an engineer in a well-equipped laboratory, of composing with the certainty of performance, and so without those too frequent "what's-the-use" stoppages, Varese was in a mood to enjoy everything that winter of his return to New York. Even formal occasions were without the usual traumatic preludes of wrenched collars and ties and the mot de Cambronne in three languages. They must have been frequent, those black-tie events, for Varese later wrote Salzedo, "My tuxedo is on vacation after its winter at hard labor." The winter included a concert in honor of Arnold Schoenberg, who had been teaching in Boston since his arrival in America. Mrs. Blanche Walton (Cowell's patroness) gave a luncheon for him in her apartment on Washington Square. Be sides ourselves, there were Charlotte and Carl Ruggles and Cowell-other guests, if any, I have forgotten. I had expected an arrogant Schoenberg because of the tone of a letter he had written in reply to Varese's request for permission to per form his Pierrot lunaire at a concert of the Inter national Composers Guild in the Twenties. On the contrary, he seemed that day a modest, quiet little man. He was probably bewildered by Ruggles' bawdy limericks in English and the hilarity they engendered. Several years later, I discovered a very different Schoenberg-neither arrogant nor quiet-in the lively humorous host who greeted friends every Sunday afternoon at his home in Brentwood, California. When someone complimented him on owning such a beautiful house, he said with a twinkle, "Yes, I now own almost one window and a half." Of course, if it was a question of his music, arrogance was and is the appropriate description.

In the spring, Slonimsky came down from Boston to rehearse the PAAC concert. Varese was de lighted with his "Mecanicien"-which in French connotes both mechanic and engine driver-as, with his penchant for nicknaming, he called Slonimsky. There was a minimum of those nerve racking stoppings and repeatings at the rehearsals of Ionisation, and Varese's suggestions were surprisingly few. This would be Slonimsky's third performance of the score for percussion and two sirens. He had given its premiere in February 1933 in New York and a second performance soon after in Havana.

The score of Ecuatorial, however, had not been finished in time for him to study it in advance. He was quick to understand the quiddity of the work and did his best to mold his ensemble to its exigencies, and the two violinists, including Charles Lichter, gave generously of their time in learning to play the theremins. (The score also called for four trumpets, four trombones, organ, percussion, and bass voice.) In spite of these efforts, the sessions were pretty grim. One trouble was that Varese had written Ecuatorial with Chaliapin's voice in his ears and Chaliapin's gift of dramatic characterization in his memory. It’s probably more important for Varese's conception of this work that the singer be able to dramatize the text than that he have an exceptional voice. I have heard only one singer, Thomas Paul, who understood this desideratum.

In a letter, Asturias had explained the origin of the portion of Leyendes de Guatemala that Varese set to music. It was the "invocation of the tribe lost in the mountains after abandoning the city of abundance," he said, and was taken from the Po poi Vuh, the sacred guide of the Quiches. Some of the lines of this profoundly poetic and intensely dramatic supplication follow:

O Builders, O Moulders! You see. You hear. Don’t abandon us, Spirit of the Sky. Spirit of the Earth.

Give us our descendants, our posterity as long as there are days. as long as there are dawns. May green roads be many. the green paths you give us.

Peaceful, very peaceful may the tribes be. Perfect, very perfect may life be, the existence you give us.

O master Giant, Path of the Lightning, Falcon! Master-magi, Powers of the sky. Procreators, Be getters! Ancient Mystery, Ancient Sorceress, Ancestress of the Day. Ancestress of the Dawn! Let there be germination, let there be Dawn.

Later Varese wrote a kind of directive for conductor and singer: "The title Ecuatorial refers to those regions where Pre-Columbian art flourished. The character of the music is intended to convey some thing of the elemental simplicity and fierce intensity of those primitive sculptures, and the singer should keep this in mind, as well as the legendary character of the entire work. The execution should be dramatic and incantatory, the singer guided by the imploring fervor of the sacred Maya-Quiche text. The dynamic indications of the score must be closely followed.... As for the organ, as all organs are different, it’s left to the conductor and organist to decide the registration that should coincide with the ensemble. In any case voix humaine or similar effects must avoided." The concert took place at Town Hall on April 15, 1934. The large audience was made up mainly of listeners eager to hear Varese's music again or those who anticipated more of the liveliness of the earlier International Composers Guild concerts.

The music to be performed was by-besides Varese-Ruggles, Salzedo, Ives, Weiss, Amadeo Roldan, Roy Harris, and Colin McPhee. There was an at mosphere of anticipation.

------- At a Maine lakeside retreat in the late Twenties, a camera recorded

harpist Carlos Salzedo's amusement at having ap propriated the name of Varese's

Arcana (1927) for his boat.

Ionisation was enthusiastically received at this, its second hearing in New York, and a repetition was clamorously demanded. As for the response to Ecuatorial, though the Varese fans clapped vigorously, there was not the same spontaneous out burst that had greeted Ionisation. Even one of the critics most favorable to Varese's music called it "a doubtful success." Another critic complained of the "raucous cacophony that almost drowned out the fine voice of Mr. Boromeo"--excellent per haps for the oratorios he understood, but that evening he seemed to me, rather than singing, to be muttering to himself in his beard (if he had worn one) like most basses. There was another reviewer who, thaugh admitting that there were "many pungent massively expressive measures," objected that "the music seemed more fitting to a text more minatory" and who may be excused for his mistake because the performance lacked the coherence Slonimsky so valiantly struggled to obtain. The music of Ecuatorial has two distinct and opposite characteristics, the one grave and supplicating for the setting of the invocation, the other as menacing as those old divinities, so fierce and feared by primitive imaginations, who were in the habit of bringing down disaster out of the skies and, as Varese remarked, were in no way related to the good Lord of the Protestant preachers.

Only Harrison Kerr--a composer, let it be noted-sensed the essential quality of the music through the disarray of the performance. He wrote in the magazine Trend, "No description could con vey any idea of the primordial cataclysmic power of the work. Certain imperfections in the still new theremins marred the ensemble now and then, and technical difficulties muddied occasional pas sages. But these were faults in performance, not in conception." Because of his dissatisfaction with this first performance of the invocation by a single bass, at the next performance twenty-six years later Varese entrusted it to eight basses. If he counted on eight bass singers adding up to one Chaliapin, his arithmetic was faulty. It was Boromeo multiplied by eight.

The rehearsals for Integrales with Martha Graham had already begun. She gave the work a sub title, "Shapes of Ancestral Wonder." "Beautiful and epic," Varese said, "though it’s obvious that Integrales directs the imagination in the opposite direction, toward the wonder of an astronomical future rather than to an ancestral past." One session I remember vividly-a special one with the conductor, Albert Stoessel, and Graham meeting to go over the score together. The get-to gether soon turned into a tug of war. In the five years since I had met her, the earnest young woman had become New York's prima donna of the dance, and a dance prima donna has the same prerogative as any other to be temperamental and indulge in tantrums. That morning Martha indulged.

With Stoessel at the piano, she began moving through the patterns she had invented, and as I watched I marveled at her technical mastery.

Stoessel's role--or so he thought--was to elucidate the music for her. Soon he was stopping her every two minutes. Angered by his criticisms, Graham stopped dead, threw up her arms, stamped, and stormed in a fury of frustration. She shrieked insults at Stoessel until he too became angry, left the piano, and started for the door, saying he was through and would not conduct for her. Varese stopped him and put a hand on his shoulder. Since I cannot endure scenes, I slipped out of the room and paced the corridor until I heard the piano again and went back. The rehearsal was quietly underway, and though Stoessel still looked grim I saw Martha flash Varese one of her luminous smiles that said either, "Forgive me my outburst," or "I forgive you your un-danceable music." I later learned that Varese had put the rehearsal back on the track by saying to Martha, "Very well, I shall announce that Miss Graham found the music too difficult for her and that Integrales had to be canceled."

----------- In his Sullivan Street studio Varese often stood at a work

table while he committed his musical ideas to score paper.

----------- A Los Angeles newspaper photograph showed conductor Nicolas

Slonimsky (right) and a group of Hollywood Bowl musicians after a rehearsal

of Ionisation in the summer of 1934.

Without further clashes came the concert at the Alvin Theater on Sunday, April 22. The hall over flowed with dance aficionados, outnumbering, it seemed to me, the modern-music addicts. There were six dance works-two solos by Graham and four with members of the group-with music by Lehman Engel, Louis Horst, Heitor Villa-Lobos, Cowell, Riegger, and Varese; and three orchestral interludes by William Grant Still, Silvestre Revueltas, and Ives.

The evening ended in thunderous applause. I have always thought applause should be of two kinds: expression of approval of performance and performers by hand-clapping, and of the work and its composer by foot-stamping. And bravos should name the beneficiary of their approbation. Other wise one never knows. That evening, did the Martha Graham bravos outshout the Edgard Varese bravos? One could not tell.

John Martin, the dance critic and a fervent follower of Graham's career, gave a different picture of the audience: "Certainly the most hectic dance event of the season took place last night at the Al vin Theater when Martha Graham, presented by the Pan-American Association of Composers, met an almost openly hostile audience." Hostile? I don't remember. Though it seems to me more likely that the dance audience was apt to have been as hostile to the music as the dance critic usually is indifferent.

Then Martin, commenting on the ineptitude of the choice of the music performed between dances, said, "The musical interludes for inappropriateness could scarcely have been surpassed.

Presumably the program-maker was not familiar with Miss Graham's dancing." The moral? Never mix dance buffs and music buffs in the same audience.

The next exciting event in that spring of 1934 was the recording of Ionisation. It was a memorable occasion, not only because Ionisation was the first of Varese's works to be made available on a disc, but also as an impressive manifestation of generous cooperation and musical comradeship.

For the Columbia Phonograph Company agreed to bring out the record after a preliminary recording had already been made and, if satisfactory, to re turn the cost of the recording to Varese. And that is how it happened that Ionisation's forty-instrument percussion orchestra was manned gratis by Varese's professional colleagues--composers and virtuoso performers. Unfortunately, I am unable to name all thirteen musicians. With my own memory reinforced by Varese's old Berlin friend, the violist Egon Kenton, who himself handled the maracas, the guiro, and the whip, I recall Georges Barrere, who played the Chinese blocks; Salzedo, who manipulated the two sirens; and Stoessel, Cowell, and Weiss, each playing one or more of the other instruments. Roy Harris was in the control room, and of course Varese's "Mecanicien" conducted.

The critics, even those still recalcitrant to Varese's music, took a lively interest in the recording and spent many words on it. There was a marked change of tone from the jocularity of the Twenties, all of the critics now treating Varese seriously, if only as the bellwether of the left. For example, this comment appeared in Phonograph Records: "The makers of Columbia records evinced an interest in contemporary music sometime back, yet the cur rent publication of a single disc containing Edgard Varese's Ionisation represents pioneering of un usual intrepidity because it marks a full turn on behalf of the most radical leftist functioning today in the music of any nation." And from the San Francisco Chronicle: "A quiet little succes de scandale is being registered by Columbia Phono graph Company with its new recording of Ionisation by Edgard Varese. The tiny little blue record came out a few weeks ago and already is a sort of national legend." Though Varese was far from satisfied with this mechanized Ionisation, with all its technical faults, its importance for him was his belief that it was the beginning of a wider dissemination of his mu sic. He also enjoyed the stir it aroused. He wrote Andre Jolivet, the French composer, then still his pupil, "Glad that Ionisation interests you. Try to hear it on a good machine--one of Bertrand's machines, if possible. The result of the recording would have been better if the engineers had followed my advice. Though, as it is, the disc is very much in demand. It would appear that it's amazing how many records have been bought by 'composers and jazz arrangers and orchestrators.' While they continue to plunder me, they prepare the way and the public. They are sowing for me."

--------------------

The Music of Edgard Varese

"I Want to Encompass Everything That Is Human"

-----------

What interests me about Varese is the fact that he seems unable to get a hearing .... The situation... is all the more incomprehensible because his mu sic is definitely the music of the future. And the future is already here, since Varese himself is here and has made his music known to a few.

Henry Miller: The Air-Conditioned Nightmare

-----------

by Robert P. Morgan -- a regular record reviewer for HF.

MILLER'S WORDS on Edgard Varese, written in the early 1940s, have been impressively borne out by recent music history. Perhaps no composer of his generation-including such figures as Schoenberg, Stravinsky, and Webern-has made a more profound influence on compositional developments in the years following World War II. Yet de spite his more recently acquired significance, Varese remains curiously apart from the main currents of earlier twentieth-century music.

At the age of thirty-two, having established him self as a successful young composer and conductor, Varese migrated to the U.S., where he remained-except for temporary visits to Europe, including one lasting five years-for the rest of his life. This journey to a new world appeared to symbolize his desire to make a fundamental break with the past, to explore freer and less circum scribed musical territories.

In a 1916 interview, three months after his arrival in America, Varese commented: "Our musical alphabet must be enriched. We also need new instruments very badly.... Musicians should take up this question in deep earnest with the help of machinery specialists. ... What I am looking for are new technical mediums which can lend them selves to every expression of thought and can keep up with thought." The U.S., relatively unencumbered with the burden of the European musical past and favorably disposed toward the development of new technologies, seemed the place to undertake the search.

All of Varese's mature works were written after his arrival in this country. Those composed earlier were destroyed, either by fire or by the composer's own hand. In this sense too he came to us without roots: With the exception of a single brief Impressionistic song written in 1906 and recently re discovered in Paris, we have no firsthand knowledge of his youthful compositions.

Varese called the first work completed in his new country Ameriques. The title was not to be taken in a purely geographical sense: He noted that it was "symbolic of discoveries-new worlds on earth, in the sky, or in the minds of men." Finished in 1921, Ameriques is scored for a very large orchestra (originally comprising approximately 140 players, but later reduced by fifteen wind instruments and several percussion), which seemingly places it in the late-Romantic tradition. Indeed, critics have often remarked that the work reflects the influence of early Stravinsky, particularly Le Sacre du printemps. Yet despite undeniable similarities between the two scores, their differences are more interesting and fundamental. Ameriques, in fact, contains the essential elements of the ma ture Varese.

The opening unaccompanied alto-flute solo, superficially similar to the bassoon passage that opens Sucre, is set out in a purely Varesean manner, alternating in sudden juxtaposition with several orchestral interpolations, which serve to ex pose the over-all dimensions of the musical space and define the chief formal property of the composition: abrupt cross-cutting between flat, essentially static orchestral planes. Whereas in Sucre Stravinsky's textural layers accumulate into an ever richer orchestral mass, eventually leading to an almost Wagnerian climax, Varese's planes re main determinedly "neutral"-non-developmental in this traditional sense.

The juxtaposed segments of Ameriques don’t cohere into climactic moments; nor do they fit into, and thus become only part of, a larger, for ward-directed motion. Rather, Varese's materials constantly combine and interact with one another while preserving their absolute identity. This quality, which supplies one of the most important components of Varese's program for "the liberation of sound," explains why one likes to speak of his materials as sound "objects." Only in the final section does one plane (in the low brass) achieve some degree of domination, ex tending itself over a lengthy portion of the composition. It’s the most Stravinskian passage of the score; yet even here the importance of the plane is defined more by pure extension than by a heightening of tension through such forward-directed developmental techniques as rhythmic compression and acceleration. Moreover, it’s always heard simultaneously with other orchestral layers at tempting to assert their own priority.

A rhythmic flow is produced (although "flow" is misleading, since one is conscious of sudden and unexpected jerks), far removed from the post Renaissance ideal of Western music. If the latter seems "organic," with its alternation of moments of tension and release recalling the process of human breathing, Varese's music (or "organized sound," as he preferred to call it) appears "inorganic," pieced together out of a sequence of violent confrontations. One event does not serve to prepare the next, nor does a second serve as a resolution or consummation of its predecessor.

There is thus a sense of almost unrelieved tension, which means, paradoxically, that the music is basically static in conception. This characteristic, perhaps more than any other, accounts for the difficulty Varese's music poses for traditionally oriented listeners, who tend to have expectations inappropriate to its underlying mechanisms. It may also explain why his earliest supporters were more often writers and painters than musicians.

Ameriques was the first of nine works written between 1921 and 1936 that constitute the entire output of Varese's principal creative period. With the exception of two pieces for full orchestra (Ameriques and Arcana), all are relatively short, ranging from approximately five to eleven minutes, and are scored for small instrumental forces.

None is written for a standard combination, and Varese's choice of instruments reflects his special sonic interests: One piece is scored solely for percussion (Ionisation), one for solo flute (Density 21.5), one for seven wind instruments plus double bass (Octandre), and two for combined ensembles of winds and percussion (Hyperprism and Integrates). The remaining two pieces, Offrandes and Ecuatorial, are vocal and also feature instrumental combinations with a large contingent of percussion.

Noticeable in this listing is the absence of strings. Although the two orchestral works contain extended passages of string writing, among the chamber pieces only the vocal Offrandes, the earliest non-orchestral composition, uses strings.

The preference, then, is for instruments with sharp and precise attacks and cutoffs.

Varese's wish to exploit the entire compass of ...

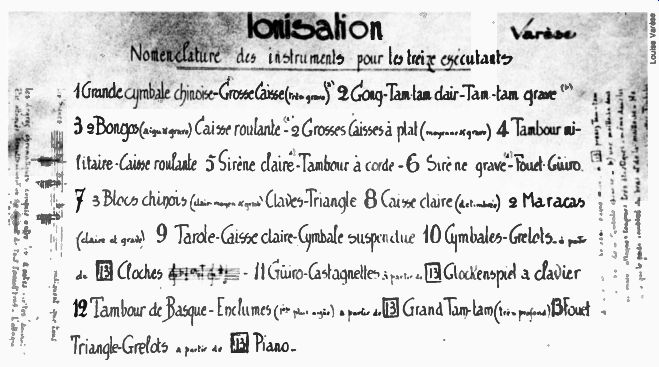

------------ In 1931, Varese wrote out a "list of instruments

for the thirteen players" for which Ionisation is scored: "1) Crash

cymbals-bass drum (very deep). 2) Gong-high tam-tam-low tam-tam. 3) Two bongos

(high and low)-side drum-two bass drums laid flat (medium and low). 4) Military

drum-side drum. 5) High siren-drum with strings. 6) Low siren-slapsticks-guiro

[a dried gourd scratched with a stick]. 7) Three Chinese blocks (high, medium,

and low)-claves [short sticks struck together-triangle. 8) Snare drum (without

snares)-two maracas (high and low). 9) Tarole [small military snare drum from

southern France]-snare drum- suspended cymbals. 10) Cymbals-sleigh bells-at

number 13 in score, chimes [tuning shown]. 11) Guiro-castanets-at 13, glockenspiel

with resonators. 12) Tambourine-anvils (first higher)-at 13, large tam-tam

(very deep). 13) Slapsticks-triangle- sleigh bells-at 13, piano." At the

sides are directions for the players. The list is part of the manuscript of

Ionisation.

-------------

... available sound is reflected in the employment of instruments with extreme ranges ( For example, piccolo and contrabass trombone define the opposite poles of the tonal field of Integrales); in the frequent use of sirens, the only "instrument" avail able at the time that could produce an uninterrupted pitch continuum; and in the appearance of two theremins, among the earliest purely electronic instruments (later replaced by the more reliable ondes martenot, also electronic), in Ecuatorial.

Finally, all of the works except Octandre and Density 21.5 require a large percussion section. Unlike the other instrumental groups, the percussion had not benefited from the general expansion of orchestral resources in nineteenth-century mu sic. Mostly instruments of indefinite pitch, they were of limited interest to composers working in a pitch-dominated style. But for Varese the percussion offered a source of variety in timbre far exceeding that of the other available instrumental types. Moreover, it had the advantage of being un burdened with the inevitable associations of musical Romanticism. (Conversely, such associations were especially strong in the strings.) Two principal points should be noted about Varese's percussion writing: the number and variety of instruments employed, far beyond the practice of any of his contemporaries, and the way they are used. Whereas traditionally the percussion had functioned mainly to emphasize points articulated by pitched instruments, in Varese they project in dependent voices on an equal footing with those of the pitched members. The originality of his achievement-and its importance for subsequent compositional thinking--can scarcely be over emphasized.

The basic factors of Varese's style are evident in all of the works written in the Twenties and Thirties. Like Ameriques, most open with an ex posed motivic figure in a single instrument that is developed and juxtaposed with contrasting element. These figures are usually grouped around a single pitch, functioning as a kind of gravitational force that draws divergences back into its field of control. This, plus the fact that the principal means of musical progression is repetition, lends the music its strongly rhythmic character. Thus the motives tend to be perpetuated through reiteration, particularly of the central pitch; and on a more extended scale, phrases (or "cycles" is per haps a better designation here) are delineated by recurrences of previously interrupted motivic units over larger time spans.

Yet Varese's repetitions rarely result in simple restatements. Motivic recurrences are usually varied; and the repetitions of the various layers that make up the total fabric are not synchronized but drift in and out of phase with one another so that their interrelationships undergo continuous metamorphosis. (This recalls Varese's definition of rhythm as "the simultaneous interaction of unrelated elements that intervene at calculated, but not regular, time lapses.") Searching for visual parallels, one thinks of a mobile-a reordering of more or-less fixed objects in ever-changing combinations--or a kaleidoscope-images that preserve that paradoxical Varesean conjunction of constant transformation and stasis.

Following the completion of Arcana in 1927, there was a notable decline in Varese's compositional activity. Ionisation appeared in 1931, Ecuatorial in 1934, and, finally, the brief solo flute piece Density 21.5 in 1936. Then complete silence descended for almost twenty years, the only exception being a compositional fragment, Etude for Espace, that was performed in 1946 but never completed.

The reasons for Varese's inactivity are no doubt many and complex. Part of the problem was apparently personal in nature, and the changing social situation brought on by the Depression-and the consequent conservative musical climate-had its effect. But Varese was also increasingly dissatisfied with the musical materials available to him.

The plans outlined in that 1916 interview, including collaboration with "machinery experts" to create new musical instruments, had been consistently frustrated. In 1930 he observed: "We’re still in the first, stammering stages of a new phase of music." Somewhat later (1939) he spoke of the gains to be derived from the development of electronic instruments: "liberation from the arbitrary, paralyzing tempered system; the possibility of obtaining any number of cycles or, if still desired, subdivisions of the octave, consequently the formation of any desired scale; unsuspected range in low and high registers; new harmonic splendors obtainable from the use of subharmonic combinations now impossible; the possibility of obtaining any differentiation of timbre, of sound combinations; new dynamics far beyond the present human-powered orchestra; a sense of sound-projection in space by means of the emission of sound in any part or in many parts of the hall as may be required by the score; cross rhythms unrelated to each other, treated simultaneously... all these in a given unit of measure or time which is humanly impossible to attain." Varese's words, which today read like a catalogue of some of the principal compositional concerns of the past quarter-century, fell on deaf ears.

Not only were his musical contemporaries unconcerned with these possibilities, but the technicians of the time showed little interest in developing the means for their realization.

Only after World War II, when tape machines became commercially available, was Varese able to take the first steps toward achieving these com positional goals. Moreover, the general musical atmosphere had again become more conducive to experimentation with new resources. It’s certainly no coincidence, then, that Varese recovered his voice at this time or that his first work in eighteen years made use of new electronic possibilities.

Deserts, premiered in 1954, uses an ensemble of wind and percussion instruments similar to those of the earlier works; but the instrumental music now alternates with taped sections to form a seven-part composite. This was the first such work to be composed; and it was created by a man approaching seventy.

Although the instrumental portions of Deserts preserve techniques established by Varese in the Twenties and Thirties, one can discern greater refinement, particularly in timbre and dynamics.

The metamorphosis of instrumental color on a single pitch reaches an unprecedented degree of differentiation.

Especially telling is the use of the piano (an instrument previously avoided) to emphasize at tacks and, since the piano sound decays quickly, then allow the sustaining wind instruments to emerge. A related factor is the extraordinarily precise indication of dynamic levels, always a Varesean pre-occupation: In places in Deserts, dotted lines are even drawn for each beat, so that the point where crescendos or diminuendos reach a given dynamic level can be exactly specified.

The tape portions are made up entirely of "natural" sounds that have been recorded and then electronically manipulated. It’s not surprising that this type of electronic composition, known as musique concrete, should appeal to Varese, as he was always disposed to work with sounds as "objects" arranged in complex spatial-temporal patterns.

Although electronic music was still in its early stages in 1954, the taped segments of Deserts have a remarkable vitality; and heard in conjunction with Varese's instrumental music they take on added meaning, the two types of music interacting with one another in mutual transformations.

Deserts was followed by the Poerne electronique, a purely electronic composition created for the Philips Radio Pavilion at the Brussels Exposition of 1958 at the request of its architect, Le Cor busier. The most sophisticated electro-acoustical equipment of the time was placed at Varese's disposal, enabling him to continue to develop unexplored sonic possibilities. The Philips Pavilion contained some four hundred speakers, with the necessary equipment to route the sound to any or all speakers at a given moment. Varese could thus realize one of his most important theoretical formulations: the projection of music in space, which enabled the motion of the sound to become an essential compositional component. As in Deserts, Varese used natural sounds, including such specifically musical ones as male and female voices, percussion instruments, and organ, but these were now combined with purely electronic sound sources such as oscillators.

Poeme electronique, performed in conjunction with projected visual images chosen by Le Corbusier, was heard by more than two million visitors to the Philips Pavilion. For the first time, Varese was the center of widespread attention and acclaim, but by ti n he was aging and no longer in good health. He was, however, able to complete the major portion of a final work and to leave sufficiently detailed sketches of the remainder for his student Chou Wen-Chung to supply a convincing ending.

This composition, Nocturnal, is scored for soprano, male chorus, and chamber orchestra. As in Ecuatorial, the chorus is treated in a stark, incantatory manner, with numerous indications for special vocal effects. In both works one finds the embodiment of Varese's wish for "an exultant, even prophetic tone.... Also some phrases out of folklore, for the sake of their human, near-to-earth quality. I want to encompass everything that is human, from the most primitive to the farthest reaches of science.- The elemental primitiveness of Ecuatorial and Nocturnal, again anticipating a direction that has since acquired importance, pro vides yet another indication of Varese's efforts to transcend the Western musical tradition, to move into a musical future that was, in his words, "open rather than bounded." In 1965 Varese was dead. Today his ideas continue to live in the works of countless younger composers. But as Henry Miller had observed some twenty-five years earlier, the future was al ready here.

-------------

The Recordings of Edgard Varese

1. Ameriques

2. Ott randes

3. Hyperprism

4. Octandre

5. Integrales

6. Arcana

7. Ionisation

8. Ecuatorial

9. Density 21.5

10. Deserts

11. Poeme electronique

12. Nocturnal

2, 4, 5, 8. Jan DeGaetani, mezzo-soprano (in 2); Thomas Paul, bass (in 8); Contemporary Chamber Ensemble, Arthur Weis berg, cond. NONESUCH H 71269, $3.96. Quadriphonic: HQ 1269 (Quadradisc), $4.96.

2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10, 11. Donna Precht, soprano (in 2); Columbia Symphony Orchestra, woodwinds, brass, and percussion, Robert Craft, cond. COLUMBIA MG 31078, $7.98 (two discs; also available singly-3, 4, 5, 7, 9, and 11 on MS 6146, 2, 6, and 10 on MS 6362, $6.98 each). 1, 8, 12. Ariel Bybee, soprano (in 12); Bass Ensemble of the University-Civic Chorale, Salt Lake City (in 8, 12); Utah Symphony Orchestra, Maurice Abravanel, cond. VANGUARD EVERYMAN SRV 308 SD, $3.98.

5, 6, 7. Los Angeles Percussion Ensemble (in 7), Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Zubin Mehta, cond. LONDON CS 6752, $6.98.

2, 3, 4, 5, 7, 9. Helmut Reissberger, flute (in 9); Ensemble Die Reihe, Friedrich Cerha, cond. CANDIDE CE 31028, $4.98.

3, 5, 9, 10. Michel Debost, flute (in 9); Paris Instrumental Ensemble for Contemporary Music, Konstantin Simonovich, cond. ANGEL S 36786, $6.98.

7. New Jersey Percussion Ensemble, Raymond Des Roches, cond. NONESUCH H 71291, $3.96 (with works by Colgrass, Cowell, Saperstein, Oak).

7. Copenhagen Percussion Ensemble, Bent Lylloff, cond. CAMBRIDGE CS 2824, $6.98 (with works by Norgaard, Lylloff).

9. Harvey Sollberger, flute. NONESUCH HB 73028, $7.92 (two discs; with works by Berio, Davidovsky, Fukushima, Levy, Reynolds, Roussakis, Trombly, Westergaard, Wuorinen).

10. Group for Contemporary Music at Columbia University, Charles Wuorinen, cond. COMPOSERS RECORDINGS SD 268, $13.90 (two discs; Columbia-Princeton Electronic Music Center Tenth Anniversary Celebration, with works by Arel, Babbitt, Davidovsky, Luening, Shields, Smiley, Ussachevsky).

Outside of his soundtrack for a film on Joan Mini, all of Varese's completed works are available on record. Since with few exceptions the compositions are on discs completely devoted to Varese, with the selection of works varying considerably from disc to disc, the best approach is to compare performances of each individual piece. Nevertheless, it seems advisable to say something about the collections as a whole.

By far the best, I feel, is the Weisberg/Nonesuch offering of four of the chamber works (two with voice), which provide an excellent introduction to Varese. The performances are generally accurate and are well balanced. The most widely representative collection, how ever, is the Craft/Columbia two-record set (also avail able on individual discs), which includes all but three of the composer's works: but here the quality of the performances is very uneven.

The Abravanel/Vanguard disc is especially valuable: Two of the works it contains are not otherwise avail able, and Ecuatorial. performed with chorus, is re corded elsewhere only in the version for solo voice.

Mehta's three readings on London are disappointing and, except for Arcana, clearly outclassed by those on other discs.

The two remaining collections feature European ensembles--Die Reihe and the Paris Instrumental Ensemble for Contemporary Music--that have a rather different approach to this music. The tempos tend to be slower and the playing less rhythmically aggressive.

The Candide disc deserves particular consideration; al though Die Reihe's performances seem to me on the whole less successful than Weisberg's, they are for the most part quite good and the selection of pieces is wider.

Ameriques (1921) -- The Abravanel performance, the only one available, was made before the appearance of the new edition brought out by Chou Wen-Chung, and there are some textual problems (such as the trumpet F, instead of E, four measures before No. 6). Although far from perfect, the performance is nevertheless a forceful one that conveys the explosive character of the piece very well.

Offrandes (1921) -- DeGaetani's beautifully warm and communicative version with Weisberg is unsurpassed.

The unidentified singer on Candide also does an excel lent job, although her lighter vocal quality is less suited to the work. On the Craft set, Precht sings consistently below pitch, and the ensemble playing is not always secure.

Hyperprism (1923) -- The best of the three versions is Die Reihe's, although it suffers from slow tempos, particularly in the pesante section. The Craft reading is livelier but marred by inaccuracies, as is the slow and studied performance by the Paris Instrumental Ensemble.

Octandre (1923) -- Although none of the three versions is ideal, the Weisberg is the most consistent. Craft's reading is also good, perhaps the best of his Varese performances. Ensemble Die Reihe plays with a softer edge than do the American groups; despite many subtleties, there is a lack of tension in their performance.

Integrales (1925) -- Here again I prefer Weisberg. He is particularly good at making the all-important connections between instruments sustaining the same notes and in keeping the various textural components clearly separated. Mehta's performance is dull and fragmented; and the two European groups are below their normal standard.

This work provides interesting examples of textual problems in Varese: Three of the five versions (Craft, Mehta, Die Reihe) have a percussion part different from the one in the score just before No. 16: and three (Craft, Weisberg, Die Reihe) have a B natural in the first trumpet four measures after No. 19, instead of the notated B flat, resulting in an uncharacteristic octave with the second trumpet.

Given this consistency of error, there must be mis takes in the parts. Or are they mistakes? The old Waldman version, recorded in 1950 under Varese's super vision (and scheduled for reissue by Finnadar), contains both of these discrepancies.

Arcana (1927)--Neither the Craft nor the Mehta version is really adequate. Mehta is clearer and more accurate, but Craft has more intensity. Unfortunately, the old Martinon/Chicago Symphony release on RCA, which is considerably better than either of these, is no longer listed. (A Boulez recording is planned by Columbia.)

Ionisation (1931) -- Here the choice is clearly the None such version with DesRoches and the New Jersey Percussion Ensemble. This is one of the best Varese performances on disc and warrants purchase even if one is not interested in the other pieces. Of the all-Varese discs, Craft, Mehta, and Die Reihe are about equally good. The Lylloff version on Cambridge is extremely poor.

Ecuatorial (1934) -- The two versions offer a distinct choice, in that one (Weisberg) uses solo bass, while the other uses male chorus. (Varese allowed for both possibilities.) [See "Varese in New York" elsewhere in this is sue -Ed.] I find the version with chorus more consistent with the general quality of the piece, but unfortunately the small group on the Abravanel recording is very un certain. Bass Thomas Paul turns in a fine performance on Nonesuch.

Density 21.5 (1936) -- The best account, by Sollberger (Nonesuch), is in a non-Varese collection. But SoIlber ger is the only flutist on records who really tries to project the dynamic levels given in the score and who differentiates sufficiently between the two alternating tempos.

Of the others, the unnamed flutist on the Craft set is best, followed by Helmut Reissberger on Candide. Michel Debost's Angel reading is very disappointing, even containing a wrong note resulting from failure to re member a previous accidental. (Actually, this raises a question concerning Sollberger's reading: Should the last note in the first main section be B natural, as he plays, or should it be B sharp, as indicated on the previous grace note?)

Deserts (1954) -- The tape parts differ: On Columbia the sounds move from channel to channel, while on Angel and CRI they remain stationary in each speaker. Since Varese was consulted for the Columbia disc, presumably this is what he wanted, and the sound rotation does bring added life to the tape portions.

As for the instrumental segments. Wuorinen's reading with the Group for Contemporary Music is much the tightest and most accurate, although it’s a bit on the stiff side. The Craft is lively but lacking in nuance, with the complex dynamic relationships particularly suffering from a lack of differentiation. The Paris Ensemble is better in this latter aspect, but its tempos are much too slow. (The second instrumental section seems inter minable.).

Poeme electronique (1958) -- This work, which is purely electronic, is available only on Columbia. (The music is, of course, limited by the two-channel format.)

Nocturnal (1961) -- The Abravanel version is the only one available, but fortunately it’s the best of his three Varese performances. The chorus, apparently the same as on Ecuatorial, is much better here; and both the soprano (Ariel Bybee) and the instrumentalists perform accurately and sensitively.

+++++++++++++++

-------------

(High Fidelity, Feb 1977)

Also see:

The Tape Deck, by R. D. Darrell