A Handel maven begins a trek through the editions and the recordings, past

and current.

Reviewed by Teri Noel Towe

[Teri Noel Towe, a partner in the New York law firm of Gan:, Hollinger, and Towe, hosts classical-music broadcasts on WKCR and WBAI . His vaunted abhorrence of moderation-the very reason we recruited him for such a task-made it impossible for us to present a complete discography in a single installment in time for Christmas, as planned: but at least the late Christmas (or early Easter) shopper will find some guidance here, more next month.]

EVERY NOW AND AGAIN friends who know that I am a Messiah fanatic ask me to recommend the best recording. My short answer is that there isn't just one-and only partly because Messiah has been so frequently recorded that there have been at least a dozen excellent accounts.

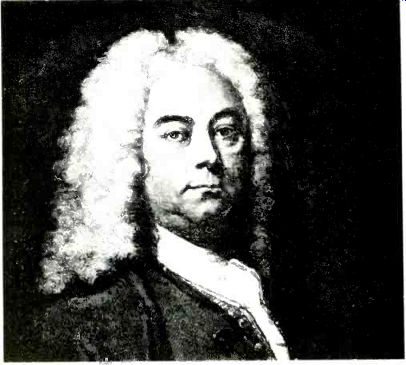

A keyboard virtuoso and composer of the highest caliber, Handel was also a practical musician and entrepreneur--an eighteenth-century Stephen Sondheim. David Merrick. Lester Lanin, and Keith Jarrett all rolled into one. He owned at least an interest in the production companies that presented his operas and oratorios. He also frequently acted as impresario, organizing and promoting his own concerts. None of his compositions was graven on stone; he considered them all subject to revision, not only to improve them, but also to meet the practical requirements of particular performances. He often altered works to suit the capabilities of available performers.

In the case of Messiah, these observations are especially pertinent. Contrary to popular belief, the oratorio was not an immediate hit in England. After its initial success in Dublin, Handel took it back to London, where it met with indifference from the general public and outright hostility from those who-with the tacit support of Edmund Gibson, then bishop of Lon don-considered it sacrilege to perform a setting of biblical texts in a theater, with popular stars as soloists.

Its first three seasons in London--1743, 1745, and 1749--Messiah flopped.

Not until 1750, a couple years after Thomas Sherlock had succeeded Gibson as bishop, did it catch on; Handel gave two benefit performances-the second by popular demand-in the chapel of the Foundling Hospital, an orphanage of which he was a trustee. Thereafter, Messiah became a staple of his annual spring season of oratorios for the rest of his life.

Practically every year that he presented it. Handel made changes, rewriting, transposing, or replacing individual numbers. Some alterations were intended to improve the work's pacing, but most were dictated by the strengths or weaknesses of singers available for particular performances. For instance, the aria "But who may abide" originally was scored for bass soloist. In 1750, 1751, and 1753, Handel was blessed with the services of the remark able castrato alto Gaetano Guadagni (later to create the role of Orfeo in Gluck's opera) for whom he wrote the revised form of "But who may abide" now familiar. About thirty years after his death, this version, with its vibrant prestissimos, began to be assigned to a bass soloist-which it never was by Handel-a practice that persists to this day, even in some otherwise "historically accurate" performances.

Handel, of course, wouldn't have given a damn about such later adaptations. A pragmatist and a businessman, he knew that changes and compromises are often necessary for the show to go on. Pace, ye righteously indignant purists, Handel surely would have endorsed the changes, cuts, and additions that have helped to insure Messiah's status as the longest-running hit show in musical history; its universal popularity has not waned in 240 years. He would not have objected to the replacement of the "obsolete" harpsichord continuo and would have understood the beefed-up choruses and orchestras later generations felt necessary for effective presentation in con cert halls of vastly increased size. He considered Messiah, like all his other works, a living, breathing organism, a document as susceptible to interpretation, change, and amendment as the United States Constitution.

In the twentieth century, however, we have become accustomed to think in terms of "final" or "definitive" versions of com positions, musical and otherwise. By the late-nineteenth century, a "standard" version of Messiah-a combination of the various alternatives that tallies with no version Handel himself presented-came to be accepted by performers and audiences alike. These choices, made for extramusical as well as musical reasons over the nearly 150 years since Handel's death, were codified-for the English-speaking world, at least-by Ebenezer Prout in his performing edition, published in 1902. For numbers that exist in more than one authentic form, Prout selected and printed only the version then most popular; since these are the versions most of us know as "definitive," a list of his choices is presented in the accompanying box.

As is well-known, Handel wrote Messiah in twenty-four days during August and September 1741, rested a week, wrote the oratorio Samson in one month, rested a few days, and then left for Dublin to present a series of subscription concerts. While he worked on Samson, his longtime friend and business associate John Christopher Smith, Sr., was busy deciphering the Messiah score and preparing the fair copy from which Handel would conduct for the rest of his life. This manuscript contains much invaluable information concerning who sang what in which production and together with evidence that can be gleaned from the composing score, surviving word books, and contemporary manuscripts copied by Smith and his assistants--reveals great deal about the various changes Handel made during the eighteen seasons prior t his death on April 14, 1759, eight days after his last performance of the work.

During the winter of 1741-42, Handel began to tamper. He rewrote the opening o "Thus saith the Lord," shortening it by two measures and changing it from an arioso t an accompanied recitative. He also sup pressed the original form of "How beautiful are the feet," a dal segno aria that sets in its central section, the words now familiar from the chorus "Their sound is gone out." He substituted another number, an alto duet leading into a chorus, to a different text that also begins with the words "How beautiful are the feet." The premiere production of Messiah in the spring of 1742 had no version of "Their sound is gone out."

--------------------

Prout's Messiah

Part II. Sinfonia

2. Comfort ye My people (tenor recit.)

3. Ev'ry valley (tenor aria)

4. And the glory of the Lord (chorus)

5. Thus saith the Lord (bass recit.)

6. But who may abide (alto aria)

7. And He shall purify (chorus)

8. Behold, a virgin shall conceive (alto recit.)

9. O thou that tellest good tidings (alto aria and chorus)

10. For, behold, darkness (bass recit.)

11. The people that walked in darkness (bass aria) 12. For unto us a Child is born (chorus) 13. Pifa (long version) 14. There were shepherds: And lo! the angel of the Lor (sop. recit.) 15. And the angel said unto them (sop. recit.) 16. And suddenly (sop. recit.) 17. Glory to God (chorus) 18. Rejoice greatly (sop. aria) (4/4 version) 19. Then shall the eyes of the blind (alto recit.) 20. He shall feed His flock (alto, sop. aria) 21. His yoke is easy (chorus) Part II 22. Behold the Lamb of God (chorus) 23. He was despised (alto aria) 24. Surely He hath borne our griefs (chorus) 25. And with His stripes (chorus) 26. All we like sheep (chorus) 27. All they that see Him (tenor recit.) 28. He trusted in God (chorus) 29. Thy rebuke hath broken His heart (tenor recit.) 30. Behold. and see (tenor aria) 31. He was cut off (tenor recit.) 32. But Thou did'st not leave (tenor aria) 33. Lift up your heads (chorus) 34. Unto which of the angels (tenor recit.) 35. Let all the angels of God (chorus) 36. Thou art gone up on high (bass aria) 37. The Lord gave the word (chorus) 38. How beautiful are the feet (sop. aria) (revised version) 39. Their sound is gone out (chorus) 40. Why do the nations (bass aria) (long version) 41. Let us break their bonds asunder (chorus) 42. He that dwelleth in heaven (tenor recit.) 43. Thou shalt break them (tenor aria) 44. Hallelujah! (chorus) Part Ill 45. I know that my Redeemer liveth (sop. aria) 46. Since by man came death (chorus) 47. Behold. 1 tell you a mystery (bass recit.) 48. The trumpet shall sound (bass aria) 49. Then shall be brought to pass (alto recit.) 50. 0 death, where is thy sting? (alto. tenor duet) (short version) 51. But thanks be to God (chorus) 52. If God be for us (sop. aria) 53. Worthy is the Lamb (chorus)

-------------------------

Indeed, the Messiah Handel introduced in Dublin was a rather makeshift affair, and the oratorio was never again presented in that form. Having taken only three vocalists--two sopranos and an alto--with him from England, Handel had to rely on local talent for the rest of his soloists. Hampered by the weakness of his tenor and basses, he ended up substituting recitatives for three arias-the original bass versions of "But who may abide" and "Thou art gone up" and the tenor aria "Thou shalt break them." He also reassigned other solos to his own singers, taking care not to tax them more than necessary.

Notwithstanding the captions emblazoned across record covers, Messiah has never been recorded as Handel premiered it on April 13, 1742-nor is it possible to do so, since the recitative substituted for "Thou art gone up" has not survived. Jean Claude Malgoire's CBS account is the latest to be billed as the Dublin version. Yet as even the most cursory scrutiny of extant sources and relevant literature shows, the musicological preparation was embarrassingly slipshod. To catalog the most egregious mistakes:

I) "Ev'ry valley" is given in the familiar post-1745 version with two measures excised from the opening and closing ritornello.

2) "But who may abide" and "Thou shalt break them" are not sung in the recitative forms; the correct aria forms of those numbers and of "Thou art gone up" are used, however.

3) "Rejoice greatly" appears in a curious, completely un-Handelian hybrid of two early forms. He initially wrote it as a strict da capo aria in 12/8. Early on, probably between the Dublin and London premieres, he shortened it appreciably, split ting the original opening section into two segments, separated by the original central section. Malgoire gives the opening section complete in the original form, then follows with the central section and shortened reprise.

4) "Then shall the eyes," "He shall feed His flock," and "If God be for us" are all sung by soprano, as written, not by alto, as actually sung in Dublin.

5) "How beautiful are the feet" appears in the dal segno version Handel discarded before the Dublin premiere. Ironically, this error inadvertently furnishes one of the album's strongest selling-points; the first recording of the aria's original version, it fills a gap in the discography and makes the set invaluable for every true Messiah maven.

6) Malgoire presents "The trumpet shall sound" in its post-1745 dal segno form rather than as the full da capo aria--Handel used in his first three productions and cuts the reprise of the opening ritornello in "He was despised." which Handel never treated as anything but a full da capo aria.

7) The duet "O death, where is thy sting?" appears in its revised twenty-four bar version rather than the original forty one bars Handel presented until 1749 or 1750.

Using period instruments and a choir of men and boys, Malgoire follows Han del's instrumentation scrupulously--too scrupulously, in fact, for he omits French horns. While there are no extant horn parts, the accounts for the benefit performances at the hospital show that two horn players figured in the ensemble. In early-eighteenth century performance practice, as confirmed by the Samson score, horns would have doubled the trumpets at the lower octave in the choruses in Parts II and III.

With an instrumental ensemble some what smaller than Handel's, Malgoire stresses the dancelike qualities inherent in many movements. This approach works to the definite advantage of the jiglike "Rejoice greatly" but seriously detracts from a contemplative aria like "I know that my Redeemer liveth." At times--such as in the arioso "All they that see Him" and the ensuing chorus "He trusted in God"--Malgoire's striving for interpretive effects seems fussy, and his undue stress on strong beats makes the instrumental articulation a little too forceful and unnatural. Mirella Giardelli's harpsichord continuo is overly reticent, especially in bravura arias like "Why do the nations." The ensemble sound, especially in the strings, is raw and scrappy. Patches of painfully poor intonation abound, and the playing, like the musicology, reeks of inadequate preparation.

The Worcester Cathedral Choir sings the choruses to a fare-thee-well, but the soloists do not join in, as Handel's did.

Soprano Jennifer Smith is most impressive.

Obviously schooled in authentic performance practice, she has a rich, well-focused voice that invites comparison with Rosa Ponselle's in its molten gold tone.

Treble Andrew J. King's singing of the Nativity recitatives and ariosos becomes downright uncomfortable. Charles Brett's is a fine, full, and focused countertenor, but his strangely detached air, particularly in "He was despised," is disconcerting. Predictably, tenor Martyn Hill's contribution confirms his thorough mastery of Handelian idiom; a pity, then, that his voice is suffused by so much anachronistic vibrato. A sensitive and effective bass, Ulrik Cold, offers an especially lovely reading of "Thou art gone up." For all its failings--including a trilingual booklet that provides no information as to which performing edition is used or which soloist sings which numbers--this is nonetheless a valuable addition to the discography. Along with the "first" already noted, the rousing "Hallelujah" chorus, one of the most thrilling renditions ever recorded-justifies the cost of the entire album.

The coolly received London premiere production is documented by Marriner's recording, accurately described as "based on the first London performance of March 23, 1743." The performing edition was prepared by Christopher Hogwood, who also plays organ continuo and provides the excellent annotations that are just one of the many strong points of this superb recording.

Apart from restoring at least two of the arias replaced by recitatives in Dublin, Handel made three major changes in this version: In the duet version of "How beautiful are the feet," he substituted a soprano for one of the altos. He restored the words "Their sound is gone out" in a tenor ario so-perhaps sung by a soprano at the first London performances. In the Nativity sequence, he replaced the accompanied recitative "And lo, the angel of the Lord" with the arioso "But lo," composed expressly for the singing actress Kitty Clive, who had gained fame as Polly in The Beggar's Opera. The presence of such a singer, the eighteenth-century equivalent of a Lotte Lenya or a Diana Ross, in the production must have been especially annoying to those antagonistic to Handel's presentation of a sacred oratorio in the theater.

Hogwood's performing edition, though commendably accurate, does contain two vestiges of the Dublin and pre-Dublin versions-the original arioso version of "Thus saith the Lord" and the abbreviated version of the "Blessing and honor" section of the chorus "Worthy is the Lamb." Technically not part of the first London production, they are nevertheless well worth having on record. A penciled indication in the composing score of the chorus, evidently in Handel's handwriting, cuts bars 39 to 53; doubtless associated with the Dublin production, this abridgment, which Handel may never have used, lends a different balance to the final choruses that is not without its peculiar appeal.

Marriner's Messiah otherwise re-creates the first London production right down to the restoration of the two bars in the opening and concluding ritornello of "Ev'ry valley." Using modern instruments and a mixed chorus, this is, quite simply, one of the finest accounts ever recorded.

From the initial bars of the marvelously wrought Sinfonia, the instrumental playing is both inspired and impeccable. Aside from the concluding "Amen," a bit flaccid and lacking in momentum, the choruses are light-footed and brisk, but tempos in the slower choruses are never inappropriate.

The soloists all give sensitive, stylish, and finely honed performances. Soprano Elly Ameling is especially noteworthy; her "I know that my Redeemer liveth" is meltingly beautiful, and the extended, but not excessive, cadenza she interpolates into "Rejoice greatly," correctly performed in the revised, short 12/8 version, is in and of itself cause for rejoicing.

1749 and 1750 were watershed seasons for Messiah, and the productions mounted in those years prompted Handel to make revisions that to a large extent have become "standard." 1749 saw the composition of the best-known form of "Rejoice greatly," in 4/4 time, and the equally familiar choral version of "Their sound is gone out," prefaced by a version of "How beautiful are the feet" that is a slightly abridged form of the opening section of the soprano dal segno aria Handel had deleted before the Dublin premiere. 1750 produced the "Guadagni" versions of "But who may abide." "Thou art gone up," and "How beautiful"; this last, a modified form of the revised soprano aria, has not as yet been recorded to my knowledge.

Messiah as Handel performed it in 1752, when Guadagni was in Ireland, is re created in the Robert Shaw recording, now more than fifteen years old but still one of the best. This production assigned Guadagni's versions of "But who may abide" and "Thou art gone up" to an alto and used the revised soprano version of "How beautiful are the feet." It also featured the short, eleven-bar form of the Pifa (generally mis called the "Pastoral Symphony") and the short version of "Why do the nations," which, with its terse and dramatically intense recitative ending, Handel evidently preferred to the familiar long version. In the recitative "Then shall the eyes" and aria "He shall feed His flock," Handel appears to have opted in 1752 for the original soprano version. Shaw, on the other hand, chooses the most familiar version-which Handel, ironically, apparently used only twice, in 1745 and 1758-in which the alto sings the recitative and the first part of the aria, the soprano the rest.

Shaw's tempos, especially in the choruses, are brisk and energetic yet con trolled. As one might expect. his chorus, only slightly larger than Handel's, acquits itself impeccably. All four vocal soloists are also first-rate; their embellishments and cadenzas, though conservative, are not too restrained. The orchestra, about the same size as the bands Handel used for his benefit performances, is of like caliber.

The best documented of all of Han del's productions of Messiah is the annual benefit performance of May 15, 1754. A complete statement of the number of participating vocalists and instrumentalists is pre served in the minutes of the Foundling Hospital's general committee, and the set of parts and the score Handel bequeathed to the hospital, copied from the performance materials used at the 1754 benefit, are still extant. The orchestra consisted of fourteen violins, six violas, three cellos, two double basses, four oboes, four bassoons, two trumpets, two horns, and timpani, with harpsichord and organ continuo. The chorus, six boys and thirteen men, was augmented by five soloists, who, the parts make clear, sang all the choruses, as concertists of this period customarily did. Second soprano Christina Passerini, who had been recommended to Handel by his old friend Telemann, was allotted only three arias--but what arias they were! In addition to "If God be for us," she sang two of the Guadagni numbers-"Thou art gone up," transposed up a fourth, and "But who may abide," boosted a fifth. The latter transposition entailed extensive reworking of the altitudinous string parts. (Incredibly, this A minor soprano rewrite is the one authentic alternative version of a number in Messiah that has not been published. Watkins Shaw elects "for practical reasons" to include a literal transposition into G minor, made a year or two after Handel's death for the conducting score Smith prepared for his son, Handel's designated successor to continue the tradition of the annual Foundling Hospital benefit. John Tobin includes neither soprano version.) Otherwise, the 1754 Messiah was identical with the one Handel presented in 1752.

-------------------

Editions Consulted

Mozart-Hiller; Breitkopf and Hand. 1803; reprinted by Kalmus from later edition.

Prout; Novello. 1902; reprinted by G. Schirmer.

Shaw, W.; Novell°, 1958; Textual Companion. Novello. 1963.

Holschneider; Neue Mozart Ausgabe, Baren reiter. 1961.

Tobin; Hallische Handel Ausgabe. Barenreiter. 1965.

--------------------

This production is re-created with extraordinary accuracy in Hogwood's own release, far and away the finest authentic-instrument account and one of the best Messiahs ever recorded. Hogwood deviates from Handel's practice in only one important particular: "As soloists cannot be expected to sing choruses nowadays, the original balance is here restored by the use of a choir slightly larger than Handel's, though fundamentally the same in constitution." Alas, boosting the number of trebles and male altos to compensate for the absence of the soprano and alto soloists does not result in quite the same choral timbre Handel expected. Why couldn't the requisite number of additional adult female vocalists have been engaged to preserve Handel's own balance? Still, in the face of Hogwood's magnificent achievement, such a cavil is perhaps ungracious.

There are those--HF's Kenneth Cooper among them (April 1981)--who do not share my enthusiasm for the Hogwood. Yet after numerous re-hearings in the two years since its release, its immediate appeal and interpretive persuasiveness remain un- dimmed and have even been enhanced by familiarity. Particularly thrilling are soprano Emma Kirkby's performance of the revised "But who may abide," incomparably exciting and compelling, and the concluding choruses, with their shattering emotional clout and near perfect dramatic pacing.

True, there are moments where that quicksilver spark of inspiration eluded the performers-particularly in some of the choruses, where tempos could have been just a hair faster--yet one shouldn't hold one's breath waiting for a more exciting account on period instruments. L’Oiseau Lyre's sound is bright, transparent, and natural, and the annotations, by Hogwood and Anthony Hicks, are excellent.

During the last five years of his life, Handel made no further alterations in the score, merely reassigning various numbers--"Rejoice greatly" was sung by a tenor one season-and reviving alternative versions. For one series of performances in the late 1750s he appears to have revived the alto duet and chorus form of "How beautiful are the feet," harking back to Dublin so many years before.

As early as 1744, Handel authorized and even encouraged the presentation of Messiah by ensembles other than his own, and by the time of his death in 1759, it had been performed in Oxford, Bristol, Bath, Salisbury, and in Gloucester and Worcester, where it was sung at the triennial Three Choirs Festival, establishing an enduring tradition. After Handel's death, John Christopher Smith, Jr., and then the blind organist and composer John Stanley continued the annual benefit performances through the year 1777, in 1784, some 525 vocalists and instrumentalists gathered in Westminster Abbey to commemorate the centenary of the composer's birth, giving rise to the tradition of gargantuan Handel performances. (There is, however, no evidence that, as frequently claimed, additional accompaniments were provided for this production.) More than a decade earlier, Messiah had "gone out into all lands." In 1772, Thomas Arne's son Michael introduced it into Germany, presenting selections in Hamburg; three years later, in the same city, C.P.E. Bach led a complete performance, with the text translated into German by poet Friedrich Gottlieb Klopstock.

In 1789, in Austria, a performance was given that was to have a radical effect on the course of Messiah's history. Baron Gottfried van Swieten, who later translated and edited the text for Haydn's Creation, had, as a diplomat in London during the late 1760s, become an ardent Handelian.

Among other Handel scores, he took back to Vienna a copy of the first edition of the full score of Messiah, published by Randall and Abell in 1767. Beginning with Judas Maccabeus in 1779, he introduced works by Handel into the annual oratorio series, given for the benefit of the Tonkiinstler Society-a Viennese musical charity. In 1789, he presented Messiah and, for this Viennese premiere, commissioned Mozart to fill out the accompaniments, largely dispensing with the keyboard continuo and replacing the tromba parts--practically unplayable for late-eighteenth-century trumpeters.

Using the Randall score and a German translation by Christian Daniel Ebeling, Van Swieten had a copyist prepare a score containing the vocal lines and Handel's string parts, together with the original dynamic and tempo markings. Onto the staves left blank for his use, Mozart added his woodwind, brass, and string parts; those of Handel's woodwind or brass parts that he chose to retain, he copied from the Randall score.

Since that score contains some, but not all, of the alternative versions either in its main body or in an appendix, Van Swieten had to decide which forms to use. He doubt less chose the versions he had come to know in London twenty years earlier; by and large, he selected the versions favored by Handel during the last years of his life and subsequently by Smith, Jr., and Stanley.

Van Swieten reassigned some of the solos to voices other than those Handel specified. He divided the six tenor numbers r n beginning with "All they that see Him" between the two soprano soloists (there was no alto soloist per se: those solos he allotted to the second soprano), assigned the 4/4 form of "Rejoice greatly" to the tenor, and gave the Guadagni version of "But who may abide" to the bass. Ironically, the only one of these assignments with no precedent whatever in Handel's practice-namely, the last-is the one that became "standard" during the nineteenth century and first half of the twentieth. Since Mozart's version was to become the basis for most, if not all, further accompaniments added to Messiah throughout the nineteenth century, Van Swieten must also take credit-or shoulder the blame-for initially shaping the "standard" score as finally codified by Prout. Neither Van Swieten nor Mozart, however, can be blamed for turning "Why do the nations" into a full da capo aria:

They were merely following the indication in the first edition. As Walsh's heirs, Randall and Abell had reused the plates from his Songs in Messiah in order to hold down costs in assembling a full score. Since no choruses figured in that collection, a da capo was indicated in the aria to provide a return to the tonic key; Handel had used the chorus "Let us break their bonds asunder" as an exciting and dramatic substitute for a reprise of the aria's opening section.

Walsh's da capo expedient was carried into the full score in error.

Van Swieten and Mozart also made a few cuts. In omitting the chorus "Let all the angels of God," these Roman Catholics inadvertently destroyed the subtle link Han del had created between this chorus and "Hallelujah," both of which quote a line from Philipp Nicolai's Lutheran chorale tune Wachet auf, ruff uns die Stimme. They also left out the aria "Thou art gone up," and Mozart replaced the aria "If God be for us" with an accompanied recitative of his own. His abridged version of "The trumpet shall sound" gives most of the demanding tromba solo to a horn. Perhaps most sur prisingly, he made no additions whatever in quite a few numbers.

Mozart's woodwind complement includes paired flutes (piccolo in the Pifa), oboes, clarinets, bassoons, and horns. In addition to two trumpets and timpani, his scoring calls for three trombones-in the "Overtura" and the chorus "Since by man came death." The original performance materials, which have been preserved, show that the trombones also doubled the alto, tenor, and bass lines in the tutticho ruses. In addition, these parts show not only that portions of some choruses were sung by the soloists, but also that the tutti choir-and this is confirmed by annotations on a surviving word book-consisted of but twelve singers!

----------- HANDEL: Messiah.

Jennifer Smith. soprano; Andrew J. King.

boy soprano; Charles Brett, countertenor; Martyn Hill. tenor; Ulrik Cold, bass; Worcester Cathedral Choir, Grande Ecurie et Chambre du Roy, Jean-Claude Malgoire, cond. [Georges Kadar, prod.) CBS MASTERWORKS M3 37854 (three discs, manual sequence). Tape: M3T 37854 (three cassettes). [Price at dealer's option.] Other Recordings Marriner; Ameling, Reynolds. Langridge, Howell; St. Martin's Academy and Chorus. ARGO D I8D3 (3).

Shaw, R.; Raskin. Kopleff, Lewis, Paul; Robert Shaw Chorale and Orchestra. RCA LSC 6175 (3).

Hogwood; Nelson, Kirkby. Watkinson, Elliott, Thomas; Christ Church Cathedral Choir (Ox ford), Ancient Music Academy. OISEAU LYRE D I 89D3 (3).

Messner; Kupper, Anday, Fehenberger, Greindl; Salzburg Cathedral Choir, Salzburg Mozarteum Orchestra. REMINGTON (3), OP.

Mackerras 11; Mathis, Finnild, Schreier, Adam; Austrian Radio Chorus and Symphony Orchestra. ARCHIV 2710 016 (3).

Stone; Addison, Sydney, Lloyd, Gramm; Han del and Haydn Society Chorus, Zimbler Sinfonietta. UNICORN (3), OP.

Dunn; Hoagland, Wallace, Gore, Livings, Evitts; Handel and Haydn Society Chorus and Orchestra. SINE QUA NON SA 2015 (3).

[Conductor unnamed); Allen, Dews. Harrison, Knowles; London Welsh Choir, Queen's Hall Players. G&T 78s (25 sides).

---------- Precisely because Mozart's additions are so exquisite in and of themselves and were written by a universally acknowledged master unabashedly working in the style of his own age, their validity and propriety have been debated. The negative view was perhaps best expressed by Moritz Hauptmann, who complained that Mozart's arrangement "resembles elegant stucco-work upon an old marble temple, which easily might be chipped off again by the weather." Perhaps; but to extend the architectural analogy, I, for one, find Mozart's work as congruent with and as complementary to Handel's as Sir Christopher Wren's late-seventeenth-century additions are with the original Tudor portions of the palace at Hampton Court.

The arrangement was published by Breitkopf and Hanel in 1803, with editorial assistance from Thomascantor Johann Adam Hiller, who had done much to promote Messiah in Germany. Influenced no doubt by reports of the 1784 London commemoration, he had presented the oratorio, with additional accompaniments of his own, using enormous forces; at the first performance he directed, in Berlin in 1785, 302 vocalists and instrumentalists participated.

Editing Mozart's arrangement must have been a bittersweet task for Hiller, who surely would have preferred to have seen his own performing edition published (the score and parts, alas, appear to have been lost), but his alterations were not as extensive as Prout and others believed. (The autograph Mozart score and the original performing materials turned up only some twenty-five years ago, and the arrangement was not published in Urtext form until 1961.) Hiller's only crucial change was to substitute his own arrangement-with bas soon obbligato!--of Handel's "If God be for us" for the accompanied recitative Mozart had written.

There have been two recordings of the Mozart Messiah. The first, recorded live in Salzburg in 1953 under the direction of Josef Messner, is based on Mozart-Hiller.

Crippling cuts (can you imagine a Messiah without "All we like sheep"?), lugubrious tempos, dry and wan singing, and cramped sound make this out-of-print recording expendable for all but the archivist. By contrast, the second, glorious in almost every way, is essential to the library of anyone seriously interested in Messiah or Mozart.

Conducted by Charles Mackerras (his second Messiah) and produced by Andreas Holschneider, who prepared the Urtext edition for the New Mozart Edition, the recording accurately represents the original production in all important respects save two: Firstly, the chorus consists of fifty-two singers rather than twelve, and the solo pas sages Mozart indicated in some choruses are sung by a Favoritchor rather than by the soloists. Secondly, the second soprano's part is divided between soprano Edith Mathis and alto Birgit Finnila, who, with tenor Peter Schreier and bass Theo Adam, make up one of the finest groups of soloists to grace any account. Overall, the performance is indescribably charismatic and atmospheric and, despite use of modem instruments and other minor inauthenticities, succeeds admirably in conjuring up images of the Palffy Palace premiere in Vienna on March 6, 1789.

Although it met with resistance initially--especially in Great Britain-the Mozart-Hiller version quickly became the performing edition most frequently encountered during the nineteenth century though not for lack of numerous others. As the century progressed, Handel, revered like a demigod, fell victim to the notion that bigger is better. The most notorious and elephantine performances of his music, without question, were those given at the triennial Handel festivals held in the Crystal Palace, Victorian London's prototype of the Houston Astrodome. At the 1859 commemoration of the centenary of Handel's death, before an audience of some 20,000 people, Sir Michael Costa led 2,765 vocalists and 460 instrumentalists in Messiah; he added parts for a full Romantic orchestra that included contrabassoons and ophicleides. Emma Albani, Adelina Patti, Nellie Melba, and Clara Butt were among the galaxy of opera stars who appeared as soloists in the Crystal Palace festivals, which continued until the mammoth edifice was destroyed by fire in the 1930s. This facet of Messiah's history has not been documented on record, and I hope that the next time one of the giant choruses like the Mormon Tabernacle Choir or the Huddersfield Choral Society is tapped to record the work, the record company will have the guts to ignore the purists' howls of horror, resurrect Costa's score, engage topflight opera stars, and re-create a full-blown Romantic Crystal Palace production, right down to the string portamentos, thereby not only performing an invaluable musicological service, but also avoiding the use of the lackluster Prout scoring or a misguided attempt at a pseudo-authentic Messiah with anachronistically gargantuan forces.

In the 1870s and 1880s, German organist Robert Franz made quite a reputation by preparing editions of choral works by Bach and Handel with additional accompaniments for "modern orchestra." His edition of Messiah, published in 1885, was used for many years by the Handel and Haydn Society of Boston, which had given the first complete American performance in 1818, and formed the basis of the score used by the late Thompson Stone for the society's 1955 Unicorn recording, now out of print. Although Stone made numerous cuts and alterations and was cajoled-or more accurately, shamed-into allowing a harpsichord in his orchestra, his recording gives a clear idea of Franz's approach, which, "though founded on Mozart [-Hiller], with the necessary completions," is both tasteful and inventive. Nonetheless, the society should one day resurrect Franz's performing edition and record it authentically and in its entirety, as a pendant to its recording of the "pure" score, conducted by Thomas Dunn-the best available bud get version, which will be discussed next month.

Messiah as it was performed in nineteenth-century Britain is documented in the first comprehensive recorded representation of the oratorio, a remarkable series of twenty-five single-sided G&T 78s made in 1906. Although arranged for woodwinds and brass to accommodate the primitive recording methods, the Mozart score was followed. Tempos are consistent with those considered the norm today. The soloists, however, provide surprises. Theirs are not large, vibrato-ridden operatic voices; the tone is light, pure, well focused, and free of vibrato. Vestiges of the performance practice of earlier times can also be detected in the treatment of cadential points; the soloists actually dare, albeit conservatively, to interpolate high notes and other embellishments. Tenor John Harrison's interpolations at the end of "Thou shalt break them" bear a close enough resemblance to Paul Elliott's in the Hogwood recording to drive the point home: These soloists could have walked into Hogwood's recording sessions, and with only a modicum of coaching in baroque embellishment, recorded Messiah in an impeccably stylish manner. ‘Plus ca change, plus c'est la meme chose'.

-HF

-------------

(High Fidelity magazine, Jan 1983)

Also see:

CLASSICAL--Behind the Scenes Music news and commentary