Classical Reviews: Inbal's Mahler cycle continues; two perspectives on Previn's return to Walton's First

FROM STRENGTH TO STRENGTH

MAHLER: Symphony No. 6, in A minor. Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, Inbal. Yoshiharu Kawaguchi, prod. Denon CO 1327/28 (2. Th. MAHLER: Symphony No. 7, in E minor.

Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, Inbal.

Yoshiharu Kawaguchi, prod. Denon CO 1553/54 (2, D). MAHLER: Symphony No. 9, in D; Adagio from Symphony No. 10, In F sharp. Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra, Inbal.

Yoshiharu Kawaguchi, prod. Denon CO 1566/67 (2, D). With the release of Symphonies Nos. 6, 7, and 9 (the latter paired with the Adagio of No. 10), Eliahu Inbal's Mahler cycle on Denon awaits only the monumental Eighth for completion. [The Eighth was due for release as this review was going to press; it will be reviewed in a forthcoming issue -Ed.]

Provocative as it may sound, these are the only recorded performances fit to stand beside Leonard Bernstein's in their total comprehension of, and identification with, Mahler's sound world. The interpretations are exciting, lucid, and, above all, idiomatic. In achieving this quality, Inbal succeeds where so many other participants in the Mahler boom have failed -and that success is brilliantly illustrated by these recordings.

The Sixth Symphony, Mahler's most frightening creation, is also one of his most unified and disciplined. Inbal understands the need to keep the music under control right up to the catastrophe of the tragic closing bars. His account of the symphony's opening movement perfectly balances the relentless march music with the surging lyricism of the theme depicting Mahler's wife Alma. The tempo is moderate, the rhythm rock-solid. The Scherzo receives a knotty reading that highlights its grotesqueness, and the two trios have a real grazioso lilt that pointedly fails to conceal the menace lurking beneath the stylized facade.

In Inbal's rendition, the Andante for once attains a genuine walking tempo without sacrificing the element of repose so necessary at this point in the drama.

Suddenly, the reason behind Inbal's slower-than average tempos for the first two movements becomes clear: In approaching the Andante this way, he softens the contrast between it and the rest of the sym phony. The music of this brief idyll sufficiently sets it apart from the rest of the work; meanwhile, Inbal maintains the dramatic momentum. Such insights typify Inbal's grasp of Mahlerian architecture and his ability to view each symphony as a whole. (In his Deutsche Grammophon recording, Herbert von Ka rajan disrupts the symphony's larger balance by taking the third movement at a comatose crawl.) The magical central episode with alpine horns and cow bells has never sounded so sensuous and evanescent as it does in Inbal's hands.

Correctly opting for two hammer blows in the finale instead of three, Inbal realizes the shattering effect better than anyone else has. Also impressive is the way in which he balances Mahler's brilliant poly phony in the movement's extended recapitulation. In bal creates the utmost tension between the musical lines without producing the sense of noise run amok that characterizes Tennstedt's performance on Angel EMI. The final chord is shattering.

The Seventh Symphony is Mahler's concerto for orchestra. In fact, comparison with Bartok's Concerto for Orchestra reveals many similarities. Both pieces employ a five-movement "arch" form, with the second and fourth movements serving as intermezzi. Both composers begin with slow introductions and depict a musical progression from darkness to light, making special use of nocturnal imagery and bird song. And in this symphony, Mahler invented what later became known as the "Bartok pizzicato"-plucking a string so hard that it snaps against the wood of the fingerboard. Successful performances of the Seventh require perfect balance be tween the four coequal sections of the orchestra, a steadfast refusal to prettify Mahler's often intentionally raucous textures (so much for Abbado on Deutsche Grammophon), and, most importantly, a sense of humor (which eliminates Solti and Tennstedt). Inbal demonstrates his understanding of the Seventh most graphically in his treatment of the landler-like scherzo and the finale. Mahler marked the creepy scherzo "not fast," an injunction both Solti and Abbado blithely ignore. Inbal realizes every ghoulish twist at a moderate tempo that lets the details register properly. The finale-a delightful glorification of the banal-is simply one of the most hilarious compositions in existence; Mahler himself marked it "allegro ordinario." In sum, Inbal and his orchestra play the pants off the piece; only Bernstein's new Deutsche Grammophon recording is more fun.

Mahler's Ninth has not lacked for great interpretations, three of which are available on CD--Bernstein's first account for CBS, his new one on Deutsche Grammophon, and Karajan's on DG. In bal now adds his name to the list while imparting his unique vision to the account.

Throughout his cycle, Inbal has lavished extraordinary attention on string phrasing. Nowhere does this prove more important than in the string-dominated textures of the Ninth's first movement. Every musical strand seems to stand out as if it were being sung by a single voice. A particularly striking example comes in the orchestral response to the ghostly chamber-mu sic cadenza that ushers in the coda, following the movement's third and final collapse. The violins appear to be on the verge of articulate speech, and the effect is a revelation.

The remaining movements of the Ninth proceed equally well. Inbal's rendition of the virtuosic Rondo Burleske may be the finest on record. He alone accurately gauges each successive acceleration to the finish, keeping the frenzy building to the final bar. While Karajan's Berlin Phil harmonic and Bernstein's Concertgebouw Orchestra can play faster, they generate less cumulative excitement.

Both Karajan and Bernstein treat the finale as an almost transcendent experience, Mahler's last attempt to come to terms with mortality. Inbal prefers a gentler approach, making this sublime Adagio a noble culmination purged of strain and torment. The perspective is similar to Bernstein's first recording of the score for CBS. The Adagio from the unfinished Tenth Symphony seems to grow naturally out of this finale, and the performance is equally satisfying.

None of these interpretive insights would matter were it not for the superlative Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra. The German radio orchestras are truly a precious musical asset. Because they receive liberal rehearsal time and give relatively few public concerts, they are capable-especially under such conductors as Inbal and Gunter Wand-of playing at a level that puts even the orchestras of Berlin, Chicago, and Vienna to shame. The Frankfurt ensemble is one of the best: What can be heard in this recording of the Ninth, taped live in Frankfurt, is in many ways superior to what Solti and the Chicago Symphony managed at Carnegie Hall last season.

Denon's recorded sound has improved as this Mahler series has progressed. It is now warm and immediate, with no audience noises intruding on the rather high playback level required for maximum impact. These are remarkable performances that belong in every collection. Playing time for CO 1327/28: 83:54. Playing time for CO 1553/54: 77:53. Playing time for CO 1566/67: 104:21. David Hurwitz

BEETHOVEN: Concertos for Piano and Orchestra: No. 1, in C, Op. 15; No. 2, in B flat, Op. 19.

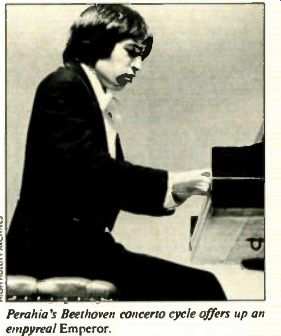

Perahia; Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, Haitink. Steven Epstein, prod. CBS Masterworks IM 42177 (D). cm BEETHOVEN: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 5, in E flat, Op. 73 ("Emperor"). Perahia; Amsterdam Concertgebouw Orchestra, Haitink. Stan Goodall, prod. CBS Masterworks MK 42330 (D). o cm When Murray Perahia and Bernard Haitink recorded Beethoven's Third and Fourth Piano Concertos as the first in HIGH FIDELITY ARCHIVES installment in a complete cycle for CBS, the performances were of such surpassing musicality, intelligence, and technical mastery that one assumed -provided the other three concertos were realized on the same level-that this would become the recorded cycle of reference, as Artur Schnabel's has been since the 1940s. CBS has now issued the recordings of the First, Second, and Fifth Concertos, and as it turns out, things are not quite as promising as one might have hoped.

above: Perahia's Beethoven concerto cycle offers up an empyreal Emperor.

The reservations one has stem from Perahia's playing in the First and Second Concertos, which does not equal the seemingly unconstrained inspiration of his ac counts of the Third and Fourth. In the present readings, there is an atmosphere if not of contrivance, then of reserve. Perahia's sedate tempo for the last movement of the First Concerto, for instance, exemplifies what has accurately been described as his tendency to be "over-polite." There is, however, enough illuminating insight in Perahia's phrasing to place this cycle in a class with such notable renditions as Fleisher's, Pollini's, and Rubinstein's (especially his 1960 set with the Boston Symphony Orchestra). And Perahia's Emperor Concerto is one of the best on record. In all five of the concertos, the adroitness of Haitink's accompaniment and the playing of the Concertgebouw Orchestra are virtually unparalleled. The sound of the orchestra and piano in the deeply resonant Concertgebouw is repro duced with accuracy and clarity, although knob-turning in some passages causes cer tain instruments to predominate one mo-ment and others the next. Playing time for the First and Second Concertos: 69:28. Playing time for Emperor Concerto: 38:39.

Thomas Hathaway

BEETHOVEN: Symphony No. 9, in D minor, Op. 125. Wiens, Lewis, Hermann, Hartwig; Hamburg State Opera Chorus, North German Radio Chorus and Orchestra, Wand. Ulf Thomson, prod. Angel EMI CDC 47741 (D).

Beethoven's Ninth has acquired an almost mythical reputation for sublimity. It is, after all, the work that determined the storage capacity of the Compact Disc, even though a 90-minute CD might have made greater sense. Interpretations of the Ninth abound on CD, so it's only fair to ask whether Gunter Wand has anything of value to tell us about Beethoven's ultimate symphonic statement. On the basis of this release, the answer is surely yes. In fact, this may well be the most generally recommendable account of the Ninth on CD. In common with conductors like Bernard Haitink and Otto Klemperer, Wand has a powerful sense of musical architecture, which he communicates in performances that invariably highlight the logic that binds together a work's various movements. His approach to the Ninth is typical, yet unlike anyone else's. The first movement has a drive and drama reminiscent of Toscanini, with particularly impressive trumpets and timpani. The scherzo, which is almost exhaustingly intense, moves like the wind, with hardly any relaxation in the trio. After so much passion and frantic activity, the Adagio achieves precisely the sense of supernal calm and unearthly tranquility it must have, with out becoming an exercise in Brucknerian stasis. Wand never loses the cantabile line and achieves a repose that refreshes rather than oppresses.

The finale keeps in sight the fact that its principal emotion is joy, not hysteria. No eccentricities of tempo mar the sense of mounting jubilation, as the movement proceeds. The chorus sings superbly, as do the soloists. The tenor's march variation moves with more uninhibited swagger than in any other performance I know. It's a superb moment, fully demonstrating the validity of Wand's approach: What other rendition has allowed such shameless prominence to bass drum and cymbals to such happily proletarian effect? Wand's performance exudes the serene confidence of a man who, having spent a lifetime with this music, trusts the composer to make his points simply and naturally. Aided in no small degree by the highly proficient North German Radio Orchestra and lovely recorded sound, both Beethoven and Wand succeed. Playing time: 66:17.

David Hurwitz

BLISS: "A Colour Symphony"; "Checkmate" Suite. Ulster Orchestra, Handley. Brian Couzens, prod. Chandos CHAN 8503 (D). o ABRD 1213. I= ABTD 1213.

Sir Arthur Bliss (1891-1975) was yet another distinguished member of the English musical renaissance that Edward El gar launched and that composers as di verse as Michael Tippett, George Lloyd, and Peter Maxwell Davies continue. A Colour Symphony (1922) was Bliss's first major orchestral work. The colors (to adopt the British spelling) assigned to each of the work's four movements--purple, red, blue, and green-evoke heraldic symbolism and pageantry. Musically, the symphony sounds like a cross between Elgar and Walton: opulently scored and harmonically pungent, with a touch of jazz here and there. It's a beautiful work that sounds rather larger than its 30-minute playing time would suggest.

Checkmate, a 1937 ballet that follows the progress of a chess game, takes its subject very seriously. It also shows some thing of the moody, tragic qualities common to much British music written be tween the two World Wars-Walton's First Symphony (1935-36) and Vaughan Williams's Fourth (1932-35) come to mind. Like A Colour Symphony, Check mate makes excellent musical use of its subject's traditional associations with royalty, conquest, and epic splendor. The ability to evoke these associations served Bliss well in his later role as Master of the Queen's Music.

Although both works have been re corded before, this CD marks the first time they have been coupled. In any case, not one of the earlier recordings was generally available in America, a fact that makes the current release all the more welcome. Vernon Handley and the Ulster Orchestra turn in expert performances that easily equal past accomplishments in this music, and the Chandos recording is typically splendid. Playing time: 56:11.

David Hurwitz

CHADWICK: Symphony No. 2, in B flat.

PARKER: "A Northern Ballad." Albany Symphony Orchestra, HegyL Elizabeth Ostrow, prod. New World NW 339-2 (D). om

It was once fashionable to deride the mu sic of the Second New England School, a circle of late 19th-century Boston composers that included John Knowles Paine, Horatio Parker, and George W. Chad wick. At a time when American music education was in its infancy, Paine, Chad wick, and Parker all went to Germany to study composition, in the process absorbing the prevailing German Romantic idiom. Yet, despite the derivative and conservative nature of their own works, the Bostonians performed no small service to American music. Like the European nationalists who were their contemporaries (in particular Smetana, Dvorak, and Tchaikovsky), the Bostonians introduced their countrymen to the advanced harmonic language and the solid musical craftsmanship of the German school.

Without that necessary first step, a truly native American music could never have developed in the ensuing generation.

Chadwick (1854-1931), whose Sym phony No. 2 dates from 1883-86, was no avant-gardist, and his symphony is closer to the spirit of Dvorak than to the chromaticism of Wagner. Equally evocative of Dvorak is Chadwick's incorporation of pentatonic folk-like melodies, fully a decade before the Czech composer's New World Symphony provided the model for such treatment of indigenous material.

Parker (1863-1919), Chadwick's student and himself the teacher of Ives and Sessions, imbued his Northern Ballad (1899) with a sentimental chromaticism that lends the tone poem a somewhat dated cast. Yet both works are formally coherent and effectively orchestrated.

The Albany Symphony Orchestra, under Julius Hegyi, is not equal to the demands of the Chadwick: The strings are thin in tone and ragged in ensemble, and the winds have occasional lapses in intonation. But the orchestra is eager, energetic, and deeply committed to this music. And one can have nothing but praise for the Albany Symphony's single-minded diligence in unearthing American music's long-buried treasures. Playing time: 50:44.

K. Robert Schwarz

DRUCKMAN: "Prism." ROCHBERG: Concerto for Oboe and Orchestra*. Robinson: New York Philharmonic, Mehta. Elizabeth Ostrow, prod. New World NW 335-2 (D). o In Prism (1980), Jacob Druckman has produced an exercise in musical time trav el. However, unlike Stravinsky in Pukinella or Respighi in any number of works, Druckman deliberately avoids complete assimilation of his musical sources-in this case, 17th- and 18th-century operas by Charpentier, Cavalli, and Cherubini, all based on the myth of Medea. Instead, Druckman strains the music through a 20th-century filter. The result is quite entertaining, much like reflections in a fun house mirror, but not all the reflections are amusing. As one might expect, some of the juxtapositions of 20th-century technique with 17th-century themes prove jar ring. What Druckman wishes to express through this deliberate discontinuity, or through the Medea theme, is unclear. Per haps it is that looking upon the past from a modern vantage point often distorts it.

Mehta meets the moderns.

George Rochberg--who, in referring to the styles of Beethoven, Mahler, and other composers in recent works, has done much to make the past respectable - shows in his plaintive Concerto for Oboe and Orchestra (1984) that historical pastiche and stylistic collage are no longer necessary excuses for tonality: One can just go ahead and write real music without worrying about Schoenberg. For this les son alone, the musical world owes Rochberg a great deal. The concerto is a rela tively subdued, melancholic, and meditative work, with most of the thinking done by the oboe, here very capably played by Joseph Robinson.

Zubin Mehta and the New York Phil harmonic seem to have both works well in hand and are accorded good sound. But why not more music on the CD? Playing time: 40:47. Robert R. Redly VERDI: "Messa da Requiem"; Te Deum.

Milanov, Castagna, Bjarling, Moscona; L. orchestra and chorus, Toscanini. Arturo Toscanini Recordings Association ATRA 240 (A, 2). (Distributed by Music and Arts Programs of America, P.O. Box 771, Berkeley, Calif 94701.) Here at last is an agreeable-sounding re lease of a justly celebrated 1940 performance of Verdi's Messa da Requiem that, until now, has circulated privately in as sorted less listenable editions. The acetate sources are remarkably well preserved and quiet, and the transfer to Compact Disc is as faithful as one could wish. Further more, the performance dates from a period when both Arturo Toscanini and the NBC Symphony Orchestra (unnamed on the la bel) were at a peak.

By 1940, the NBC Symphony, which had been a remarkable assemblage of excellent young players from the start, had attained a homogeneity that made it equal in most respects to the orchestras of Bos ton, New York, and Philadelphia. As for Toscanini, many of his broadcasts and recordings after he left the New York Phil harmonic in 1936 had been less expansive in tempo and more energy-charged than before. But by 1940, he was again conducting with the breadth and freedom of tempo (always controlled by his sense for formal coherence) and the dramatic accentuation and inflection of line that had been characteristic of his performances with the Phil harmonic. As a consequence, his 1940 concert of the Requiem was at once relaxed and powerful, and it remains one of the greatest on record.

---------

FORMAT KEY

LP, Cassette, Compact Disc, Videocassette, Videodisc, Open reel

RECORDING INFORMATION

(A) analog original; (D) digital original

Large symbol beneath title indicates reviewed format.

Small symbols following catalog number of reviewed format indicate other available formats (if any). Catalog numbers of all formats of a particular recording usually are identical except for differing prefixes or suffixes. Catalog numbers of formats other than the re viewed format are printed only if their basic number, differ substantially from that of the reviewed format.

Arabic numeral in parentheses indicates number of items in multi-item set. Unless otherwise indicated all multi-LP sets or in manual sequence.

---------

However, rating the 1940 performance as highly as it deserves should not cause one to underrate the 1951 RCA recording, which will be reissued soon on CD. In his liner notes for this album, Toscanini biographer Harvey Sachs wonders why Toscanini never approved the 1940 broad cast for commercial release: "The recording contains some superb singing, especially from Milanov and Bforling," he writes. " Castagna and Moscona also sing well, although not at their partners' level ... Orchestra and chorus are outstanding ... The sound [in Carnegie Hall] has none of the unpleasantly tinny quality that mars many of the NBC broadcasts." The few errors by the soloists that may have bothered Toscanini "occupy in all less than a minute of the Requiem's total length" and are of a kind that "we, nearly half a century later, can easily put into perspective." However, I hear other flaws that occupy more than a minute, although I can still put them in perspective: The orchestra and chorus do not sound consistently together until the "Recordare." The offstage trumpet notes in the "Tuba minim" are cracked repeatedly. The soloists do not re lax and sing at their best until well into the "Kyrie" (and, as Sachs observes, Milanov later becomes nervous again and ruins her high B flat in the "Libera me"). Moreover, the microphone picked up only enough of Carnegie Hall's reverberation to give most sections of the score clarity and amplitude, but not enough to prevent the violent sections from sounding hard and shallow. In addition, the biggest climaxes are cut back by a volume limiter not compensated for in the transfer to CD. In contrast, the 1951 RCA recording was assembled largely from rehearsal tapes. With no audience or radio transmission to worry about, the soloists, chorus, and orchestra made fewer mistakes than the 1940 forces did during their live broad cast. The soloists in 1951 did not include a Milanov or a Bjbrling, but the quartet was better balanced: The beautiful singing of the soprano (Herva Nelli) and the tenor (Giuseppe di Stefano, who sang well until after the "Ingemisco") were matched this time by the superb voices and musician ship of contralto Fedora Barbieri and bass Cesare Siepi. The NBC Symphony was playing marvelously in those years, and the chorus was the wonderful Robert Shaw Chorale. Like the performances of 1940, the 1951 recording took place in Carnegie Hall. But the empty auditorium and better microphones produced a more spacious and resonant sound in 1951 than had been possible 11 years before.

The differences in these two interpretations are not an instance of a relaxed early performance being followed by a tense, less expansive one in Toscanini's last years. They are an instance of the sort of changes in expressive detail that occurred in many of Toscanini's performances from one year to the next but that did not diminish the overall impact of those performances. The isolated 1951 passages are faster for dramatic effect, and some pas sages are more expansively treated in the later version than in the earlier one. Rarely has more than one version of a Toscanini interpretation been made commercially available. The proper response in this case, it seems to me, is to recommend both. It remains only to add that ATRA's CD of the 1940 Requiem also contains Toscanini's wonderfully clear and eloquent performance of Verdi's Te Deum from the same broadcast. Playing time: 99:50. Thomas Hathaway WAGNER: "Der fliegende Hollander." Schunk, Estes, Salminen; Bayreuth Festspiele Orchestra and Chorus, Nelsson. Philips 416 300-2 (2, D). o 416 300-1 (3). The postwar Bayreuth tradition of Wagner performance has been extensively documented on commercial recordings, beginning with the London releases of the old Knappertsbusch Parsifal and Keilberth's Lohengrin and Der fliegende Hollander. Philips was given the honor of creating a stereo document of the '60s and 9 70s, including the later Knappertsbusch Parsifal and the dazzling Karl Bohm Ring. In light of that often illustrious lineage, it is discouraging to have to greet this Hollander in less than glowing terms.

Philips has done a predictably splendid job of harnessing the Bayreuth acoustic and seeing to it that the voices and orchestra emerge in pristine balance. But one can say little for the performance. Production values were always of primary consideration at Bayreuth, but when the casts included the likes of George London, Hans Hotter, Theo Adam, Astrid Varnay, Leonie Rysanek, Birgit Nilsson, and so on, one experienced aural thrills as well. The present recording, taped in 1985, captured the last revival of seven of Harry Kupfer's now legendary production. It put Simon Estes on the vocal map once and for all, and he was heralded by all who saw him as the Dutchman of the day.

How soon critics and public forget, it seems, the greats of the past (even as re cent as Theo Adam). I heard Estes in the role in Boston in the late '70s and found him stolid and remarkably dull. My memories were not altered by listening to this Bayreuth performance. Devoid of the trappings-Kupfer's concept is that the story is but the deluded hallucination of a hysterical Senta-it is a rather dispiriting affair. There is a staunch reliability in the way Estes plows through the role, but there is no attempt to project the meaning of the words or to shade and inflect the line. Lisbeth Balslev's wiry voice has no particular color, and its core melts under the pressure of the performance's intensity. There is a certain excitement in the way she handles the Ballad, but in the big duel with the Dutchman, "Wie aus der Ferne," a raucous quality creeps in that makes the tone altogether ugly. From that point on, Balslev never quite recovers her poise.

Matti Salminen makes a sonorous, suitably boisterous Daland, Graham Clark a small-voiced but musical Steuer mann, Anny Schlemm a characterful Mary, and Robert Schunk a rather pedestrian Erik. Woldemar Nelsson conducts a fleet, energetic, slightly lightweight but very exciting reading of the score, and hearing the music in that Bayreuth acoustic is always a thrill.

Unfortunately, Kupfer's production is based on the original Dresden version that omits the Redemption motif. And at score's end, some of the repeated chords are deleted, replaced by frightening crunches that sound like a preplanned collapsing of parts of the set. This should have been corrected in a patch-up session. Playing time: 133:58. Thor Eckert, Jr.

THEATER AND FILM

CONTI: The Right Stuff" Symphonic Suite; "North and South" Symphonic Suite. London Symphony Orchestra, Conti. Bill Conti, prod. Varese Sarabande VCD 47250 (D). o 704.310. cm C704.310.

Certainly one of the most successful film composers in the business, Bill Conti may also be one of the most important. I said may be. While his best efforts reveal a solid command of the orchestra and an ability to find new ways of approaching clichéd subjects, his worst can be banal in the extreme. Something of both sides is represented in suites from two recent Conti scores, The Right Stuff and North and South. The score to The Right Stuff walks a dangerous line, masterfully evoking Hoist's The Planets and Tchaikovsky's Violin Concerto, yet never quite wallowing in them to the point of plagiarism. North and South dishes up gobs of sugary pap, all dominated by an inane main theme--Gone with the Wind it ain't. For once, the London Symphony is underserved by Varese Sarabande's digital sonics. Those interested in catching Conti in a more imaginative vein are directed to his score for FIX, currently available only on vinyl (Varese Sarabande TV 81276). Playing time: 37:22.

Noah Andre Trudeau

------------------

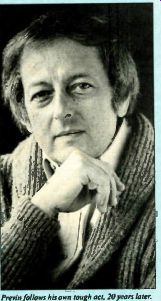

----- Previn follows his own tough act, 20 years later.

WALTON: Symphony No. 1, in B flat minor; Crown Imperial; Orb and Sceptre. Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Previn. James Mallinson, prod. Telarc CD 80125 (D).

Andre Previn's 1967 RCA recording of Sir William Walton's turbulent First Symphony with the London Symphony Orchestra has long been regarded as the benchmark performance of this 20th-cen tury British masterpiece. Unaccountably, though, it disappeared from the catalog only a few years after it was issued. That regrettable situation has been rectified by the release of Previn's new recording of the symphony with the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra on Telarc.

Fortunately, Previn's interpretation has changed very little over the past two decades. A few passages (notably the climaxes of the first and fourth movements) are treated somewhat more spaciously than before, but this doesn't interfere with the conductor's prevailing dynamic approach, which shows that this symphony is music still very much of our own time.

Moreover, Previn acutely defines the basic mood of the piece-the threat of impending war and the eventual triumph by the forces of good against evil. The only thing that keeps this version from being definitive is the slightly disappointing recording: It's full, powerful, and resonant enough, but the crucial timpani part booms more than it hits, keeping the instrument's sound from striking one's solar plexus as it should. That aside, Walton's finest orchestral work has never received a finer recording on disc. Walton's two popular coronation marches-Crown Imperial and Orb and Sceptre--are likewise brilliantly done (and somewhat better record ed), though I would have liked a broader overall tempo in the former.

Bill Zalcariasen Andre Previn's 1967 Walton First on RCA was justly acclaimed as the touch stone for all subsequent recordings. It combined hair-trigger precision with smoldering lyricism in a way that truly enhanced the stature of this wonderful symphony. Under any circumstances, it would have been a tough act to follow. How sad, then, that Previn doesn't even seem to have tried: His new performance on Telarc utterly lacks the punch of the old. The Royal Philharmonic sounds tired -it plods through the Waltonian rhythmic thicket, never once attaining the bite of Alexander Gibson's Scottish National Orchestra in a far more gripping performance on Chandos (CD 8313), to say nothing of the way the London Symphony sounds in Previn's earlier version.

The coda of the finale reveals just how seriously Previn has gone wrong. The all important writing for antiphonal timpani sounds soggy, and the tam-tam part is mostly inaudible. The elegiac trumpet solo, with its jazz inflections, utterly lacks atmosphere and tenderness. In the closing pages, the orchestra seems to have trouble staying together even at the leaden tempo Previn adopts. As in his recent Telarc recording of Vaughan Williams's A London Symphony, Previn seems to have with drawn into himself as an interpreter, pulling back from every major climax and al lowing the tension to seep away. The two coronation marches come off better, though it was a mistake to opt for the abridged version of Crown Imperial, especially on disc.

Telarc's recording, as seems to be its custom these days, offers a plush sound that is short on treble information.

Though the climaxes are well balanced, especially in the symphony, they lack visceral impact. The marches demonstrate Tel arc's trademark mike-in-the-bass-drum sonics--vulgar in the best sense and undeniably effective. (Although the symphony does not employ a bass drum, this brighter sound would have been better suited to it.) The symphony's second movement, "Andante con malinconia," has become "Andante con maunconia" in Telarc's rendering. Somehow, this lapse seems representative of the whole boring enterprise. Playing time: 59:04.

-- David Hurwitz

Also see:

The CD Spread: Ozawa's Carmina Burana; Mravinsky's Tchaikovsky symphonies; Gould's Goldberg Variations