Classical Reviews: Mozart and Beethoven E-flat Quintets; more Hummel concertos; rare Ravel cantatas; and delights from Delius. Dvorak, Villa-Lobos, and others.

TWIN BILL FROM LEVINE AND A TWO-CITY TEAM

MOZART: Quintet for Piano, Oboe, Clarinet, Horn, and Bassoon, in E flat, K. 452.

BEETHOVEN: Quintet for Piano, Oboe, Clarinet, Horn, and Bassoon, in E flat, Op. 16. Levine, Ensemble Wien-Berlin. Steven Paul, prod. Deutsche Grammophon 419 785-2 (D).

Neither of these quintets is a momentous piece, notwithstanding that Mozart called his "the best work I have composed" at the time he wrote it, at age 28. He had in fact already written the Sinfonia concertante in E flat, K. 364, the Haffner Symphony, and all his major choral works except the Requiem, as well as other works whose poignancy causes them to assume a greater eminence in our minds than they may have had in his.

Mozart may have felt he achieved something in his quintet, in the way of for mal and tonal balance, that especially pleased him as a composer who, as Haydn was to observe, possessed both heart and science. However, if he did, one will not learn what it was from Stanley Sadie's notes for this album, which are a model of the sort of structures that can be built up out of words that say nothing ("The piano is sometimes equal participant, sometimes retiring accompanist ... and occasionally takes the lead"). And I am not the first who has failed to hear in this slight work what it is that so pleased its composer.

Beethoven wrote his quintet at an earlier stage of his musical development, al though he was nearly the same age as Mozart had been at the time he composed K. 452. Opus 16 is often said to be less a chamber work than a miniature piano concerto, but that ascribes to the piano a function as protagonist that, structurally speaking, it does not have--even though it sounds almost continuously, and much of the time in the foreground. In fact, the winds and piano develop the musical material together, in chamber fashion, in each movement of the Beethoven quintet; and it is only because the wind writing is less sophisticated than Mozart's, while the piano writing is already resourceful and imposing, that the keyboard seems to dominate. The instrument remains more of a collaborator than in any of Beethoven's piano concertos.

It is partly James Levine's own gifts as a collaborator that make him the great artist he is, no less in chamber music than in opera. His playing in both of these enjoy able works is even more animated at times than Murray Perahia's in his recording of them (CBS Masterworks MK 42099), and it maintains a strong tensile outline with out sacrificing sensitivity. Where required, Levine withdraws without fading to insignificance, and one is always aware that his mind is the guiding force behind the performances' cohesive shape, without ever being made to feel that he is out to establish that fact.

The Vienna/Berlin wind players are exceptionally well matched and perform beautifully, except that the hornist makes a great many picturesque noises one doesn't expect to hear from a modern, valved instrument. Only some of these can have been intentional. Much of the horn writing in Mozart's quintet, as in his horn concertos, is deliberately comical, but the same is not true of Beethoven's writing for the instrument. The recorded sound is very beautiful, although when I listened over headphones, the reverberation seemed somewhat manufactured, and the complete and abrupt cessation, whenever a performer stopped playing, of any of the shuffling I had heard him do up to that moment made me wonder what sort of suppressors and isolaters might have been used. Over speakers, however, this effect was not noticeable. Playing time: 51:42.

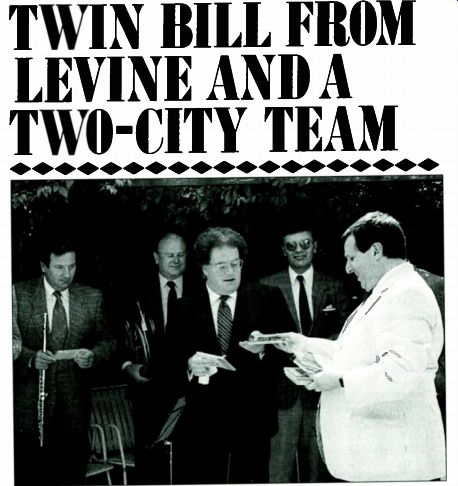

Thomas Hathaway In the foreground. James Levine (left) and producer Steven Paul. with Ensemble Wien-Berlin flutist Wolfgang Schulz (not heard on this disc). hornist Gunter Hisigner. and bassoonist Milan Turkovie. (Missing from the picture are clarinetist Karl Leister and oboist Hansjoig Schellenberger.)

------------

BARTOK: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra No. 2; Concerto for Piano and Orchestra No. 3. Menuhin, Fischert; Philharmonia Orchestrat London Symphony Orchestrat, Furtwangler, Markevitcht. Lawrance Collingwood and David Bicknell. prods. Price-Less D 15100 (A). (Distributed by Outlet Book Co., 255 Park Ave. South, New York, N.Y. 10003.)

A valuable reissue from this new mid-price label. If my memory is accurate, Yehudi Menuhin has recorded Bartok's Second Violin Concerto four times, but none of his other performances beats this one, which dates from 1953. As a Bartok interpreter, Wilhelm Furtwangler may not have ranked as high as some, but on this occasion his close spiritual rapport with Menuhin assured a performance of great dignity and fidelity to the score. Nevertheless, in spite of my admiration for the performance, I find it hard to feel much affection for the work.

The composer's Third Piano Concerto is different. It is among the most tender of modern classics, and this recording of it is one no piano lover should be without.

First issued in the mid-1950s in Britain, it was never released in America. What's more, it has never been reissued here in any form. Early in her career, the marvelous Annie Fischer won two Hungarian state awards for her interpretation of this concerto; it is most Romantic, light years distant from the frigid, unappealing ac count recorded by Bartok's widow -for whom the concerto was written.

Strangely, though, this is Fischer's Barry Douglas only recording of the work. For those who are accustomed to the brittle, "hard shell" conceptions offered by most performers, hers will come as a revelation. Until such time as Deutsche Grammophon reissues the classic, deeply human, near-definitive readings of all three of Bartok's piano concertos by the much lamented Giza Anda and Ferenc Fricsay, this ranks as the best Bartok Third on disc. Playing time: 61:58.

Thomas L. Dixon

BRAHMS: Piano Quintet in F minor, Op. 34; Works for Piano (4). Douglas; Tokyo String Quartet. Jay L. David Saks, prod. RCA 6673-2 (D). et= Ballade in B, Op. 10, No. 4; Capriccio in G minor, Op. 116, No. 3; Intermezzo in E, Op. 116, No. 4; Capriccio in D minor, Op. 116, No. 7.

Not only the four solo pieces rounding out this release make the young Ulster pianist Barry Douglas the central attraction here.

I can't help feeling that RCA could have recorded the quintet without making the string quartet sound quite so top-heavy.

Douglas doesn't exactly overpower his colleagues; on the contrary, he shows a great sensitivity in the fundamental chamber-music values of balance and give-and take. Acoustically, though, during most of the passages in which he plays, from the quartet you hear the first fiddle plus a sort of harmonic wash, and the inner voices more or less go by the board--a pity, especially with a quartet as solid as the Tokyo.

Douglas won first prize at the 1986 International Tchaikovsky Competition in Moscow, so it goes without saying that he has the technique to make this music's considerable demands seem inconsequential. Four bars into the first movement, the sudden sixteenth-notes unmistakably pro claim the presence of a powerhouse at the keyboard. Unfortunately, at that passage's recapitulation, Douglas jumps the gun where Brahms builds in a sort of notated pause, and he also reveals inconsistency in his grace notes and mordents. Otherwise, one can find little to fault in these splendid performances: The F minor Quintet's dreamy slow movement and the solo E major Intermezzo seem to me exceptionally high-quality Brahms.

Incidentally, Richard Freed's notes turn Brahms's Opus 88 and Opus 111 from quintets into quartets. On balance, I incline to suspect Mr. Freed less than some overeager RCA copy editor. Playing time: 61:21. Pau/ Moor Lydia Mordkovitch BRAHMS: Sonatas for Violin and Piano: No. 1, in G, Op. 78; No. 2, in A, Op. 100; No. 3, in D minor, Op. 108.

Mordkovitch, Oppitz. Tim Handley, 1 / 4 1) prod. Chandos ABRD 122 7 (D). a CHAN 8517. m ABTD 1227. (Distributed by Harmonia Mundi, U.S.A.)

This perfunctory reading by violinist Lydia Mordkovitch and pianist Gerhard Oppitz of Brahms's three sonatas for piano and violin (as they were originally titled) neither goes to the heart of the composer's soaring lyricism and gentle sadness nor touches our own. The duo glosses over the surface of the notes without looking for any meaning in them: Crescendos re main an accumulation of sound rather than of intensity, while the softer dynamics are not gentle or haunting but suggest merely the absence of emotion.

Though their accounts actually last a little longer than the average for these works, one feels that the artists are in fact rushing, for there is no natural ebb and flow to their phrasing. The performance unfortunately can boast neither of the excellence of its recording technique nor of the musicians' techniques. The violin is re corded with so much echo around it that it sounds fuzzy, and Mordkovitch's pressed tone is further marred by slight imperfections in intonation.

With so many beautiful versions of these works available (notably the 1985 Angel recording of Perlman and Ashkenazy), this team could be of more service if it were to unearth lesser-known repertory or premiere new works. Playing time: 71:24.

-Michelle Krisel

DELIUS: Orchestral Works (2); Choral Works (2). Walker, Allent; Ambrosian Singers. uP Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Fenby.

Christopher Palmer, prod. Unicorn-Kanchana DKP CD 9063 (D). (Distributed by Harmonia Mundi, U.S.A.) Orchestral works: Dance Rhapsody No. 2; Intermezzo from "Fennimore and Gerda." Choral works: Songs of Sunset ; An Arabeskr: "Languor" ... lovely word; and I would not contest Christopher Palmer's claim that we find "this state of rapture . . . more frequently in Delius's music than in that of any other composer." Certainly it pervades all the works recorded here, except for the vigorous, whimsical Dance Rhapsody; that exudes vigor, and even ends loud, which in Delius's tender, introspective music almost never happens. All the other works here derive from what Eric Fenby calls "a theme which obsessed [Delius] increasingly from his early opera Koanga, through the choral works Appalachia, Sea Drift, Songs of Sunset to An Arabesk -the transience of creaturely love, its partings, its frailties, and its separations." The Songs of Sunset dominate this se lection, and they get an outstanding performance from two ideal soloists, an un surpassed chorus, and one of London's best orchestras, all conducted by today's leading living Delius expert. (After advanced syphilis left Delius completely blind, Fenby served for the final decade as his amanuensis, writing down the last scores the composer dictated, note for note.) Rather self-defensively, Fenby states here that "in all his choral works Delius always wanted to hear the orchestra as a first priority, and we bore this in mind in making this recording." For my taste, Thomas Allen they rather overdo it, particularly with regard to soloists Sarah Walker and Thomas Allen, who sound unnecessarily far from their microphones. That makes it less easy to understand Ernest Dowson's touching words, even with the text in the leaflet.

-------------

FORMAT KEY

CD Cassette Compact Disc Videocassette Videodisc

RECORDING INFORMATION

(A) Analog original (D) Digital original

Large symbol at left margin indicates reviewed format. Small symbols following catalog number of reviewed format indicate other avail able formats (if any). Catalog numbers of for mats other than the reviewed format are printed only if their basic numbers differ substantially from that of the reviewed format.

Arabic numeral in parentheses indicates number of items in multi-item set.

------------

The surge at the end, however, on "They are not long, the days of wine and roses," brings a passage of Delius at his best.

In An Arabesk, the composer takes his text (translated by Philip Heseltine, a.k.a. Peter Warlock) from Jens Peter Jacobsen, the Dane who also gave us the Gurrelieder.

I question Fenby's pronouncement that it "exemplifies the best of Delius," but for any true fan of the composer its availability alone makes this a tempting recording.

Playing time: 64:41. Paul Moor

Dvorak: Symphony No. 7, in D minor, op. 70. Cleveland Orchestra, Dohndnyi. Paul Myers, prod. London 417 564-2 (D). DVORAK: Symphony No. 7, in D minor, Op. 70; The Golden Spinning-Wheel, Op. 109. Scottish National Orchestra, Joni Brian Couzens, prod. Chandos CHAN 8501 (D). ABTD 1211. (Distributed by Harmonia Mundi, U.S.A.)

Christoph von Dohnanyi's account of Dvorak's Seventh Symphony with the Cleveland Orchestra is another success in his traversal of this composer's symphonies. Never becoming manic, Dohnanyi conducts with Beethovenian vigor and brings out a wealth of orchestral details without fussing over them. He keeps things beautifully balanced and maintains a tension that never slackens, yet he doesn't push. It is a bracing and exhilarating performance. The almost startling clarity of orchestral detail is a tribute not only to the Decca/London recording engineers--who here have produced yet an other demonstration-class disc--but to the virtuosity of the Clevelanders. The precision and beauty of their playing are extraordinary, and they have a sense of ensemble that a great string quartet could envy.

Neeme Jarvi's reading of the Seventh shares roughly the same timings as Dohnanyi's (it is only 22 seconds slower), but little else. His conception is more expansive and Romantic, and while it does not lack for vigor, it casts the music in a rather mysterious Brucknerian mold. The re corded perspective might well have been chosen for this conception: It is slightly recessive and lacks a bit of London's sense of presence and definition. Jarvi has a way of beautifully shaping individual phrases, but, overall, his performance does not match the energy and high voltage of Dohnanyi's. Also, as fine as the Scottish National Orchestra is, it is outclassed by the Cleveland ensemble.

The Chandos disc has a major advantage in that it offers almost another half hour of music in Jarvi's stirring, characterful performance of Dvorak's symphonic poem The Golden Spinning-Wheel. Whatever possessed London to issue a CD with only 36:25 of music on it? Playing time (Chandos CHAN 8501): 64:50.

Robert R. Reilly

HUMMEL: Concertos for Piano and Orchestra in A minor, Op. 85, and B minor, Op. 89. Chang; Budapest Symphony Chamber Orchestra, Pd!. Herser Zoltan, prod. Marco Polo 8.223107 (D). (Distributed by Harmonia Mundi, U.S.A.) In the early 19th century, everyone appeared to know that Johann Nepomuk Hummel (1778-1837) was a genius.

His contemporaries described him as both the inheritor of Mozart's melodic gift and grace and the principal rival to the young Beethoven. A century and a half after Hummel's death, we can discover why he was included in the pantheon, and also puzzle over the obscurity that engulfed his work as Romanticism swept everything before it. This is in large part thanks to Ian Hobson's superb set of Hummel's six piano sonatas (on three Arabesque CDs) and Stephen Hough's very fine performances of Hummel's Piano Concertos in A minor, Op. 85, and B minor, Op. 89 (on Chandos). The sure sign of a revival is duplication, and now the program of the Chandos disc is replicated on a Marco Polo CD with performances that surpass it. Without knowing the size of the Budapest Symphony Chamber Orchestra, one can hear that it has the requisite weight for Hummel's brilliant and sometimes powerful orchestral accompaniment-which was rather lacking with the English Chamber Orchestra. The players and conductor Tamas Pal seem to have the style of this music in their bones. With leisurely but never slack tempos, they outpoint their English rivals in the expression of felicitous details.

Korean pianist Chang Hae-won plays with marvelous fluidity and shading, and the rapport between her and the orchestra is superb. In short, these are the finest performances of this music I have heard.

They are a must for lovers of early 19th century music, and will be a special treat for lovers of Mozart, Hummel's teacher and benefactor. The same singing line, the same operatic orchestral accompaniments, and an almost equal talent for themes of deceptive simplicity and exquisite beauty will be found in these two concertos. Hummel is not exactly like Mozart, but more like Mozart on his way to becoming Chopin.

I have always thought the opening Allegro of Opus 89 to be a masterpiece, and have used it for years to stump musical friends in games of "Who's That Composer?" Anyone who thinks Hummel is a lightweight should listen to the substantial four-minute orchestral introduction, which almost operatically prepares for the entrance of the piano. The following Larghetto could only have been pulled off so brilliantly by a true master, while the Vivace finale is full of high spirits and fun. If there is a little froth in it, it is that of true champagne, not beer. The Opus 85 concerto is equally beguiling and charming, if a bit less powerful. The all-digital recording is first-rate. This enterprising label should employ the same team to survey the rest of Hummel's piano concertos. Playing time: 71:27.

Robert R. Reilly 5 LISZT: Sonata in B minor; Ricordanza ("Etudes d'execution transcendante," No. 9); Grandes Etudes de Paganini: No. 4 (3rd version), No. 3 ("La campanella"); Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6, in D flat.

• Lucchesini. John Fraser. prod. Angel

• EMI CDC 49063 (D). BEETHOVEN: Sonatas for Piano: No. 14, in C sharp minor, Op. 27, No. 2, "Quasi una fantasia" ("Moonlight"); No. 29, in B flat, Op. 106 ("Hammerklavier").

• Lucchesini. David Groves, prod.

Angel EMI CDC 47738 (D). Andrea Lucchesini recorded the Liszt B minor Sonata in 1984 at the age of eighteen. By the time he reached twenty-one, he felt, regrettably, up to Beethoven's daunting Hammerklavier.

The young pianist has the requisite technique for Liszt, and then some, but he also lets the music breathe. In the more subjective sections of the sonata, he displays affecting lyricism and poetry; the fugato emerges finely chiseled, crystalline.

In La campanella he does original things with the grace notes, and his bravura-es-Andrea Lucchesini pecially his trip-hammer repeated octaves-makes the Hungarian Rhapsody exciting.

For some mysterious reason, Lucchesini displays far more fidelity to the Liszt scores than to the Beethoven. Barely into the opening of the Moonlight Sonata, he begins to ignore the composer's unequivocal injunction "always pianissimo," in vesting the three repeated G sharps in the right hand with much of the doom-ridden portentousness of the Fifth Symphony.

And speaking of portentous, he really goes haywire in the Hammerklavier. He had a golden opportunity here-to play it, for a change, the way Beethoven specifically notated it. Instead, he has turned his back on the score and heeds most of the pernicious "traditional" barnacles that have come to encrust this misinterpreted score.

I must leave it to more skilled mathematicians to reckon the overall effect of Lucchesini's playing not 138 but merely 100 beats to the minute in the first movement of the Hammerklavier, not 80 but 70 in the second, not 92 but 66 (and even 50) in the third, and in the fugue, marked 144, as little as 120. It all gets so fraught with meaning that the third movement turns, essentially, into a dirge. I have yet to discover anyone with the transcendental technique and the necessary chutzpah to play this sonata the way Beethoven wrote it. Still, Lucchesini bears watching. At least in Liszt, he already definitely de serves hearing.

Playing times: 58:50 (49063); 66:30 (47738). Paul Moor RAVEL: Alcyone; Alyssat. Nicolescost, Denizes, Meensl, Glas hoft; Bamberg Symphony Orchestra, Soudant. Rizzoli CD 2005 (D).

The small but enterprising Rizzoli label has given valuable service by issuing the first recordings ever of two substantial early works by Maurice Ravel: the cantatas Alcyone and Alyssa. Written in 1902 and 1903, respectively, as entries into the Prix de Rome, they were both unsuccessful, the prizes going to two composers so obscure they are not even listed in Baker's Bio graphical Dictionary of Musicians. Nevertheless, these are fine works, even though there isn't much to hear in them in the way of individual personality.

Alcyone and Alyssa are both scored for three soloists and a good-sized orchestra.

The former involves a Greek queen who has premonitions of the fate of her missing husband, and at the conclusion the king's lifeless body is brought back. The music of 5 Alcyone is for the most part more conciliatory than one might expect from the situation; its closest sonic counterpart would seem to be Debussy's equally early cantata La Demoiselle elue. Alyssa, however, is the more striking work -not because of greater originality, but for its unconventional structure and unusual influences.

This cantata is more overtly dramatic, dealing with an Irish legend involving a prince's tragic love for a fairy and his conflict between romance and duty to his king. Strangely, much of the first part of the work recalls the Middle East-inspired scores of Rimsky-Korsakov, with most of their enchanting exoticisms intact. The remainder of the cantata--not surprisingly, considering how similar the stories are--seems to have taken its inspiration from Massenet 's fantasy-opera Esclarmonde.

Certainly the climactic passages are as ex citing and as grand as anything in that score. At any rate, it is a rewarding listening experience, as the early works of most great composers usually are.

This beautifully recorded disc features four fine singers, the most prominent being soprano Mariana Nicolesco. Her plummy voice may not sound indigenously French to some ears, but her tone is gorgeous, while her style in phrasing and diction is virtually faultless. As a postscript, the excellent conductor, Herbert Soudant, has successfully sung Wagnerian tenor parts; this critic heard him do a more than-respectable Siegfried a decade ago. Playing time: 52:59.

Bill Zakariasen

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: A London Symphony; Fantasia on a Theme by Thomas Tallis. London Philharmonic Orchestra, Haitink. John Fraser, prod. Angel EMI CDC 49394 (D).

One forgets nowadays that not all too long ago people tended to say England's list of great composers ended with Henry Purcell, who died in 1695. We realize now that the first half of this century brought an extraordinary resurgence, with Edward El gar, Ralph Vaughan Williams, William Walton, and Benjamin Britten leading the field. Vaughan Williams, full of years and the composer of nine symphonies, eventually looked back on this one, his second, as his personal favorite.

--- Bernard Haitink

Although it has its feet planted squarely in Brahmsian Romanticism, Vaughan Williams made it unmistakably English, not only by quoting Big Ben but by employing his personal variant of the melos of authentic British folk music. The sym phony reveals itself to the listener at once, much more immediately than any of the composer's others. EMI, however, seems to want us to listen to this excellent performance of it not as program but as absolute music; William Mann's entertaining notes, although they refer in passing to the composer's own program notes for the work, relay very little of the quite definite program for the four movements that the composer had in mind. Odd.

With every good new recording of the Fantasia that comes along--such as this one--I always hope it may encourage American music lovers finally to get better acquainted with Thomas Tallis (c. 1505 1585), whose music inspired this glowing homage from Vaughan Williams four centuries later. Both the music and the re corded sound here evoke the majesty of English cathedral architecture. Bernard Haitink and this excellent orchestra, in both works, rise handsomely to the occasion. Playing time: 65:51.

- Paul Moor

VILLA-LOBOS: Quinteto em forma de choros; Quintet; Trio. Groupe instrumental de Paris. Andre Poulain, prod. Adda CD 581035 (D). (Distributed by Qualiton Imports, Ltd. 39 28 Crescent St. Long Island City, N.Y. 11101.)

VILLA-LOBOS: Bachianas braslIelras, Nos. 1, 5, and 7. Hendricks; Royal Philharmonic Orchestra, Boaz. Brian Culverhouse, prod. Angel EMI CDC 47433 (D).

Heitor Villa-Lobos, a Brazilian Vivaldi, produced more than 700 works, only a score of which are currently available on disc. The centennial year of his birth was 1987, and it produced some recordings that offer at least a small remedy for this neglect. These two illuminate different facets of the composer's vast output.

The French CD gives us three exquisite chamber works: the Quinteto em forma de choros for winds (composed in 1928, revised in 1953); the Quintet for Harp, String Trio, and Flute (1957); and the String Trio (1945). This centennial offering is beautifully performed by the Groupe Instrumental de Paris. Only the Quinteto em forma de choros is otherwise available, but a performance of this high quality is always welcome. The other quintet bears a close resemblance to, and emerges favor ably in comparison with, works by Ravel and Roussel for similar ensembles including harp. The dreamy Lento is utterly be guiling.

The String Trio is another work of the highest quality, written in a more serious vein, with a beautiful Andante. One can only hope that the Villa-Lobos centenary brought to the fore other chamber works of this caliber from the vast number of compositions he created.

The Angel EMI CD features the music for which Villa-Lobos is best known: his colorful, exotic, folk-inflected Bachianas brasileiras-of which Nos. 1, 5, and 7 are presented here. Himself a cellist, Villa-Lobos developed an affection for the coagulated sound of massed cellos: The improbable combination of eight of them is used in Nos. 1 and 5. In the latter, the texture is considerably relieved by the addition of a soprano vocal line, here sung ably by Barbara Hendricks. In No. 7, the longest of the Bachianas, Villa-Lobos shows what he could do with full orchestral resources.

The piece is alternately raucous, lyrical, coarse, exhilarating, meditative, and massive. Enrique Batiz conducts the Royal Philharmonic Orchestra in a lively and hot-blooded performance with fine sound.

Playing times: 59:42 (Adda CD 581035); 60:03 (Angel EMI CDC 47433). Robert R. Reilly

Barbara Hendricks

-------------

Also see:

Sony CDP-507ESD Compact Disc player (review, Oct. 1988)