AMAZON multi-meters discounts AMAZON oscilloscope discounts

INTRODUCTION

"Here's your rubber gloves. Go follow Joe." For much of the second half of the 20th century, this was the ultimate safety training method for many facilities. Fortunately, safety training professionals have managed to get two critical messages across:

1. Bad training is worse than no training at all.

2. Good training is both an art and a science.

This section defines "good" training and shows how it can augment a safety program.

Employers and consultants alike can use the information. Consultants can use the information to help set up training programs for their clients. Employers can use it to evaluate training consultants and/or take preliminary steps to set up their own training programs.

Note: This information is applicable to all types of technical training. Refer to the American Society for Training & Development website, www.astd.org, for training details.

Safety training definitions

For the purposes of this section, training is defined as a formal process used to generate a desired positive change in the behavior of an individual or group of individuals. Notice the use of the word formal. Training must be "on purpose." Never allow training to just happen.

Organize it; develop clear, measurable, and achievable objectives; administer the training, and evaluate the results. The training program and the administration of the training must then be documented.

Training is not the same thing as education, although training may well include education. Education is used to add to the cognitive skills and abilities of an individual or individuals. In other words, education teaches you how to think, while training modifies your behavior and teaches you how to do.

Behavioral modification is the core of training; however, there are many different types of behavioral modification. Three examples follow.

1. Many training companies offer training courses in which they attempt to teach general electrical safety procedures. While these courses are generally excellent, they do not directly address the specific procedures of each student's company. Rather, the courses emphasize the importance of good safety and show clients what should be done. The behavioral change that occurs is an increase in the safety effort. Such an increase will lead to many benefits; however, students will need additional safety training in their own specific job requirements.

2. Many in-house training programs teach the safety aspects of the maintenance or operation of a range of specific types of equipment. For example, a four-day program that teaches the maintenance of low-voltage power circuit breakers will spend great amounts of time discussing and showing the safety aspects of the particular equipment. This type of behavior modification is relatively specific in that it teaches detailed procedures for a class of equipment-low-voltage power circuit breakers. The desired behavior is the use of proper safety techniques to ensure that students will safely maintain their breakers.

3. A manufacturer's training program on a specific piece of equipment is a third example.

When the manufacturer of an uninterruptible power supply (UPS) offers a course on the operation and maintenance of its UPS system, very specific safety procedures are taught. In this instance, the manufacturer knows that good maintenance and operation will result in fewer problems. However, the manufacturer also knows that trained personnel must perform the maintenance safely. Here, the desired modification is reduced to a relatively few, very specific procedures.

In each of the examples just given, the training programs should be prefaced with educational objectives. An educational objective is a specific, measurable behavioral change required of the student. For example, in a lockout-tagout course, an objective might be as follows: "The student is expected to determine that a given system has been de-energized by correctly performing the three-step voltage-measurement process." A complete list of objectives should precede every module in a training program. The use of objectives allows the trainer and the trainee to be measured accurately and objectively. All the training discussed in this section will be objective-based training.

Training Myths

The electrical safety industry has at least two major training myths. These myths hurt or in some cases eliminate the implementation of good training programs.

Myth #1: My People Can Learn by Just Doing Their Job. This is the ultimate in "go follow Joe" thinking. The fact is that today's electrical systems are too complex to permit self-training unless it is very well organized and documented. The best result from such an approach will be slow, very expensive learning curves. The more likely result will be employees who learn improperly and make potentially grave errors.

Misconceptions are among the biggest problems for professional trainers. Adult learners have substantially more trouble unlearning a concept than they do learning one. While experience is definitely the best teacher, experience should be prefaced with a properly organized and presented training experience, with well-defined objectives.

Of course, well-designed self-training programs are an excellent source of training. The key word here, however, is designed. Simply turning an employee loose with an instruction book is not effective and can be very dangerous for the employee.

Myth #2: My Supervisors Can Train My People. Training is a part of every supervisor's job, but it should not be allowed to become the only part for three basic reasons. First, in today's highly regulated workplace, supervisors have their hands full with the day-to-day requirements of supervising. They simply do not have the time to put in the detailed effort required for good training. Second, good technical or supervision skills do not necessarily include good training skills. The ability to train well is an art. The third consideration is the "person with a briefcase" syndrome. Employees tend to listen closely and learn from a trainer from outside the company. The feeling is that this person brings a fresh viewpoint to the job. Frankly, this belief has some merit. The outside viewpoint can often instill skills and ideas that are not available from inside.

Conclusion

1. Insurance companies are increasing safety requirements for their insured companies.

2. The technology of power systems continues to spiral upward.

3. Systems grow at an ever-increasing rate.

4. Regulatory requirements continue to increase in number and complexity.

All these facts demand that employees be trained. Good training is available from a variety of sources.

COMPARISON OF THE FOUR MOST COMMONLY USED METHODS OF ADULT TRAINING

Introduction

Four types of training methods are in common use today: classroom, computer-based training (CBT), Internet (Web-based) training (WBT), and simple video training. CBT and WBT will be called self-training in later parts of this section. Caution must be used with the CBT, WBT, and video-based training programs. OSHA, in two interpretation letters dated October 11, 1994, and November 22, 1994, states the following:

In OSHA's view, self-paced, interactive computer-based training can serve as a valuable training tool in the context of an overall training program. However, use of computer-based training by itself would not be sufficient to meet the intent of most of OSHA's training requirements.

Our position on this matter is essentially the same as our policy on the use of training videos, since the two approaches have similar shortcomings. OSHA urges employers to be wary of relying solely on generic "packaged" training programs in meeting their training requirements.

Safety and health training involves the presentation of technical material to audiences that typically have not had formal education in technical or scientific disciplines. In an effective training program, it is critical that trainees have the opportunity to ask questions where material is unfamiliar to them. In a computer-based program, these requirements may be by providing a telephone hotline so that trainees will have direct access to a qualified trainer.

Equally important is the use of hands-on training and exercises to provide trainees with an opportunity to become familiar with equipment and safe practices in a nonhazardous setting. Many industrial operations can involve many complex and hazardous tasks. It is imperative that employees be able to perform such tasks safely. Traditional, hands-on training is the preferred method to ensure that workers are prepared to safely perform these tasks.

The purpose of hands-on training, for example in the donning and doffing of personal protective equipment, is twofold: first, to ensure that workers have an opportunity to learn by experience, and second, to assess whether workers have mastered the necessary skills. It is unlikely that sole reliance on a computer-based training program is likely to achieve these objectives.

Thus, OSHA believes that computer-based training programs can be used as part of an effective safety and health training program to satisfy OSHA training requirements, pro vided that the program is supplemented by the opportunity for trainees to ask questions of a qualified trainer, and provides trainees with sufficient hands-on experience. In order for the training to be effective, trainees must have the opportunity to ask questions. The trainees' mastery of covered knowledge and skills must also be assessed.

In conclusion, it is possible in some cases to use computer-based training in meeting refresher training requirements, provided that the computer-based training covers topics relevant to workers' assigned duties and is supplemented by the opportunity to ask questions of a qualified trainer, as well as an assessment of worker skill degradation through auditing of hands-on performance of work tasks. This section will compare and contrast each of these methods of training as they apply to adult learning.

John Mihall and Helen Belletti's "Adult Learning Styles and Training Methods" presentation handouts, dated February 16, 1999, state: "The term 'pedagogy' was derived from the Greek words 'paid' (meaning child) and 'agogus' (meaning leading). It is defined as the art and science of teaching children. The term 'Andragogy' was coined by researchers of adult learning in order to contrast their beliefs about learning to the pedagogical mode. Malcolm Knowles first introduced the concept in the United States in 1968. The concept of andragogy implies self-directedness and an active student role, as well as solution-centered activities. It was derived from the Greek word 'aner' (with the stem andr-) meaning man, not boy.

Mihall and Belletti's handouts also point out the following differences between children and adults as learners.

1. Adults decide for themselves what is important to learn. Children rely on others to decide what is important.

2. Adults need to validate the information based on their beliefs and life experiences.

Children accept the presentation at face value.

3. Adults expect what they are learning to be immediately useful. Children expect what they are learning to be useful in their long-term future.

4. Adults have experience upon which to draw and may have fixed viewpoints. Children have little or no experience upon which to draw and are relatively clean slates.

5. Adults have significant ability to serve as a knowledgeable resource to the trainer and fellow learners. Children do not have the ability to serve as a knowledgeable resource to teachers or classmates.

Basic Assumptions for Adult Learners. Adult learners expect and enjoy independence; they like control and like to take control. Learning, for them, is a process of sharing with one another. They need to know why they need to learn something before undertaking the process of learning it. Therefore, the subject matter must be applicable to their life, presented so adult learners understand why they need to know the information; they can then "buy into" and absorb what is being presented. To achieve this, the training must have credibility with the audience.

Adult learners are pragmatic and want to be able to apply new knowledge immediately.

Generally speaking, most adults have trouble tolerating the idea of studying anything that can't be applied to tasks they plan and expect to perform. They are problem or task centered and the adult learning experience is a process in which the adult increases competence to achieve maximum potential in life. Most have many experiences; therefore, the training must draw on adult-learner experiences and anyone in the class can also share their experiences.

Most adult learners come to the classroom highly motivated and eager to learn, especially if they have arrived there voluntarily. They learn in order to cope with real-life tasks and generally do not group together by age or sex but by their experiences.

Adult Learning Principles. Again, referencing Mihall and Belletti's handouts, several adult learning principles must be considered in the development of any training program.

The training must:

1. focus on real-world situations and problems.

2. emphasize how the learning can be immediately applied.

3. relate the learning to the goals of the learner.

4. relate the materials to the learners' past experiences.

5. allow debate and challenge of ideas.

6. listen to and respect the opinions of the learners.

7. encourage learners to be resources to each other (and the trainer) in a classroom setting.

8. treat learners as adults.

9. give learners orderly control.

Rate of Retention When Adults Learn. Some of these statistics may surprise many people, but over a three-day period of time, using the different methods of learning, adults retain different percentages of what they learn. Adults retain 20 percent of what they hear only, 30 percent of what they see only, 50 percent of what they see and hear, and 90 percent of what they "say as they do." It becomes obvious from these statistics that the more interactive the training is and the more that learners draw on their own life experiences, the more knowledge is retained.

Classroom Presentation

Following are the main advantages of classroom training:

• The learners are kept together and on the same point.

• It is easier to control the training time.

• It is very useful and cost-effective for large groups (20 or more people).

• If properly facilitated by the trainer, incorporated interaction draws on the learners' experiences and knowledge.

When classroom training is adequately interactive, large volumes of knowledge can be disseminated to all class participants, making the training extremely beneficial to both the learners and the facilitator.

Following are some disadvantages of classroom training:

• The training can be extremely dull and boring if it is not broken up into 45- or 50-minute increments.

• If proper interaction between the learners and facilitator isn't incorporated, it is difficult to gauge if the participants are actually learning anything. This has to be controlled through the use of proper, ongoing evaluation of training as previously described in this section.

Classroom presentation that is structured with exercises and/or role play not only has the advantages listed above but also aids retention. Remember, if adults only hear things, the average retention is only 20 percent. Structured presentation keeps learners actively involved and allows them to practice new skills. Adult learners who combine saying and doing the tasks retain 90 percent of the information disseminated in the classroom.

Structured classroom training requires more preparation time, may be more difficult to tailor to every learner's situation, and needs sufficient time built into the training time for exercise completion and feedback.

The authors of this handbook agree that structured classroom training is the type of training that consistently provides the desired results and develops a more highly skilled and accident-free workforce.

Computer-Based Training (CBT) and Web-Based Training (WBT)

Self-training programs such as computer-based training (CBT) and Web-based training (WBT) have increased in popularity in recent years. Both CBT and WBT are excellent for some training tasks and, if used properly, can be an extremely efficient use of training budgets. The biggest advantage of CBT and WBT is that either or both can be worked into an employee's schedule very easily, and they are very cost-effective ways of administering and documenting employee training. In an article by Gary James titled "Advantages and Disadvantages of Online Learning," he states: "There are several distinct advantages and disadvantages of designing, developing, and delivering web-based training (WBT). By carefully weighing your audience and training content against this list of advantages and disadvantages, you should be able to better judge if what you have in mind is right for Web dissemination." Following are some of the advantages of Web-based training:

1. Turnaround of finished product is quicker.

2. Training delivery is easy and affordable.

3. Cross platform-you can deliver your training course to any machine over the Internet or company intranet without having to develop a different course for each unique platform.

4. No separate and distinct distribution mechanism is needed-WBT can be accessed from any computer anywhere in the world while at the same time keeping delivery costs down.

5. WBT requires less technical support.

6. Content can be easily updated.

7. Installation on private networks is an option for security or greater bandwidth.

8. WBT saves on travel costs and time.

9. Internet connections are widely available.

10. WBT-based development is easier to learn than computer-based training development.

11. Access is controllable.

12. Direct access is available to many other training resources.

Following are some of the disadvantages of Web-based training:

1. Limited formatting of content in browsers: WBT may not resemble CBT because of bandwidth constraints. If content relies on media bells and whistles, or particular formatting, the Internet may not be the best delivery system.

2. Bandwidth/browser limitations may restrict instructional methodologies. If the content relies on much use of video, audio, or intense graphics, and your audience isn't on the proper equipment, Internet delivery frustrates the learners.

3. Limited bandwidth means slower performance for sound, video, and large graphics.

4. Someone must provide Web server access and control usage.

5. Downloading applications requires time.

6. Student assessment and feedback is limited.

7. Many of today's Web-based training programs are too static with very little interactivity.

CBT and WBT training programs are very similar. CBT has many of the same advantages and disadvantages as WBT except for the Internet limitations of WBT and the ease of updating WBT.

With humans, memory fades quickly. If you don't use a skill or a thought process for a long period of time, you tend to lose the information. OSHA recognized this long ago.

OSHA 29 CFR 1910.269(2)(iv) states: "An employee shall receive additional training (or retraining) under any of the following conditions: [one of the conditions listed in 1910.269 states the following] NOTE: OSHA would consider tasks that are performed less often than once per year to necessitate retraining before the performance of the work practices involved." This statement means that if employees do not perform a task for a period of 12 months, they must be retrained on that task for OSHA to consider them "qualified" to perform the task safely. OSHA 29 CFR 1910.332(c) states: "Type of training. The training required by this section shall be of the classroom or on-the-job type. The degree of training provided shall be determined by the risk to the employee." CBT and WBT are considered "classroom training" and are excellent sources of refresher training for qualified electrical workers to remind them of the rules or proper techniques.

CBT can be very cost-effective if "off-the-shelf" packages can be implemented for generic training. If the training must be customized to suit the customer's needs, CBT can be very expensive at first. After the initial investment, you own a 24-hour-a-day trainer that can handle any number of learners simultaneously. WBT is also very cost-effective. Both WBT and CBT generally enable the owner to reduce or eliminate travel costs associated with training. When adult learners are utilizing WBT or CBT, they feel in control of their training and receive immediate feedback as to how they are progressing. The interaction with the computer screen actively engages the adult learner and provides more trainee satisfaction. Adults enjoy working at their own pace and on their own schedule.

For the owner, both WBT and CBT provide computerized systems for tracking the progress of trainees and provide inexpensive standardization of training when training is being facilitated in several different departments, plants, and locations.

Computer-based training and Web-based training are used widely by colleges and universities to reach a greater audience than is available by use of traditional classroom instruction. Another advantage of CBT or WBT type of training is that learners can use the computer and/or computer software during free time and pace the learning to suit their schedule and perceived needs. Some of these characteristics of CBT and WBT have built-in disadvantages. One big disadvantage is that training at a very slow pace allows learners to lose interest and drop out of the training altogether.

CBT can be an efficient method for upgrading employees' skills, but this is not always the result. If CBT is your choice of training, it is imperative that you select the best product, product developer, and presentation technique. CBT, like all other training, must be supervised. This type of training is a complete failure if the learner is simply placed in a room with a computer and left alone. If no one is available to answer questions and make sure that the proper level of understanding is developed, no quality learning is taking place.

Adults can watch a video presentation several times, but if they leave the training with more questions than answers, the experience may not be worthwhile. To maximize the CBT training experience, a supervisor or mentor must be available to answer questions and develop understanding on information that is not immediately understandable to the trainee.

The only way computer-based training is truly an efficient and effective training tool is if the sessions are monitored and supervised by a qualified person who can ensure that training schedules are followed and questions are answered and who is available to develop complete understanding of the training materials presented in the training program.

Video training

Video training, when properly used, is an extremely effective tool. When overused or used improperly, video training loses effectiveness very rapidly.

Short, high-impact training videos are an excellent tool for use in safety meetings or for training sessions to either teach new skills or simply elevate awareness on any particular topic. They are also an excellent tool for educating employees on certain processes such as the use of specialty tools like exothermic welding and a myriad of other topics.

The insertion of short (5 to 20 minutes) videos, dealing with the topic being taught, into a training presentation serves several purposes. Adding the visual aspect aids in knowledge retention, breaks up the monotony of a lecture, clarifies the material being presented in the lecture, and serves as a refreshing break for the learners. It has been said millions of times that a picture is worth a thousand words. This is a very true statement and one that needs to be considered when a trainer is selecting video materials to include in any training program.

Video producers tend to overdo the dramatics in videos. For example, in electrical safety training videos dealing with arc-flash, the video producers put some type of fire agent on the back side of the electrical worker. The worker then performs some act that produces an electric arc to simulate igniting the electrician's clothes as an electrical arc would do in the event of an arcing failure. The worker then flails around with his back side on fire and eventually falls on his face and continues to burn. This is not real life and these episodes water down the video and diminish its credibility. Typically, electrical workers are facing the arc source and therefore are burned on the front of their body. We teach very small children to stop, drop, and roll in the event their clothing catches fire. So the safety video has just depicted a situation that adults with life experiences do not relate to very well. Another common mistake witnessed in safety videos is to picture an electrical worker wearing class 00 rubber gloves with a beige label and rated for 500 volts ac, or class 0 gloves with a red label rated for 1000 volts ac with class 2 leather protectors over them.

OSHA mandates a minimum distance between the rolled bead of the rubber glove and the end of the gauntlet on the leather protectors for class 00 and class 0 rubber gloves of at least ½ inch, 1 inch on class 1 gloves, 2 inches on class 2 gloves, 3 inches on class 3 gloves, and 4 inches on class 4 gloves. Common sense must prevail throughout the training session, including during video presentation, to maintain credibility with the folks being trained in the industrial workforce. But in the case of electrical safety videos, the number of producers is very limited and the market is so small, there is not much choice but to use the videos that are available and on the market.

When using safety videos in a training program, the training facilitator needs to mention and refer to them in a positive way during the presentation and build interest among the trainees in seeing the videos. Then when it is time to introduce the video, the trainer must use some technique to grab the interest of the learners prior to starting the video. One great way to do this is to tell the class something like this: "This is one of the finest electrical safety videos on the market; it includes actual accidents that have been reenacted for the video" or "There are five flagrant violations of OSHA and NFPA 70E rules in this video.

See how many you can identify" or "This is an excellent video but it contains violations concerning the wearing and inspection of rubber insulating gloves; see if you can identify them." When trainers use this technique, learners are tuned into the video presentation because they have been offered a challenge and expect to have to respond to questioning once the video presentation has ended. Training facilitators need to follow up on their challenge to the students and ask a few open-ended questions about the video that require the response of several learners.

Conclusion

In summary, CBT and WBT are excellent for some training, but both of these types of training need to be monitored by someone who can act as a mentor to ensure that an acceptable amount of knowledge is transferred to the learner. The highest-quality training is achieved by use of structured lecture with quality hand outs and limited use of video training incorporated into the program. The use of written quizzes and final exams forms the basis of an excellent record-keeping system and provides documentation of exactly what topics were covered in the formal training session. Also keep in mind that 100 percent is the only acceptable score on any test that relates to any type of workplace safety. Electrons are not very smart, but they move at the speed of light, or 186,000 miles per second. Electrical workers can't move their hands or run faster than the speed of light. Therefore, if they can't outrun electrons, they must possess enough knowledge about basic current flow and electrical safety to allow them to outthink electricity.

They deserve the highest-quality training they can be provided.

The next section details some of the requirements of training delivery and explores the pros and cons of training delivery methods. In addition, on-the-job training is discussed in some depth.

ELEMENTS OF A GOOD TRAINING PROGRAM

If you do not know what it is made of, it is hard to build. Because of this fact, many companies, even those with strong training commitment, have poor training programs. From a safety training standpoint, three types of training can be defined-classroom, on-the-job, and self-training. A complete adult training package must include all three of these methods assembled in a formal, planned program. Each method has certain critical elements, some of them shared.

Element 1: Classroom training

Classrooms. When most of us think of classrooms, we think of the rooms where we went to grade school-the small, cramped desks with books underneath the seat, chalk dust, and the spinsterly schoolmarm. Adult classrooms need to be designed for adults.

1. The classroom should be spacious but not huge. Students should not be cramped together and should have sufficient table or desk space to spread out their texts and other materials.

2. The classroom should be well lit and quiet. Dim lighting is more conducive to sleeping than learning, and noise from a nearby production facility can completely destroy the learning process.

3. The classroom should be as far from the students' work area as possible. This serves two purposes.

(a) A remote location tends to focus the student on learning.

(b) Interruptions by well-meaning supervisors are minimized.

4. All required audiovisual equipment should be readily available. Screens should be positioned for easy viewing and controls should be readily accessible to the instructor. Avoid using a whiteboard for a screen due to the glare.

Laboratories. The adult learner must learn by doing. For safety training, learning by doing means laboratory sessions and/or on-the-job training. Many of the design features mentioned for classrooms also apply to laboratories. However, there are a few special considerations.

1. Avoid using the same room for both laboratory and classroom. A room big enough for both is usually too large for effective classroom presentation. Too small a room, on the other hand, crowds the students during lecture and laboratory. Equipment needed to train students in procedures should be placed in positions where it does not interfere with the lecture presentation.

2. Initial training on safety procedures should be done on de-energized equipment.

3. Students should work in groups to help support each other.

Materials. Student materials can easily make or break a training program. Although a complete material design treatise is beyond the scope of this guide, a few critical considerations follow:

1. All student text sections should be prefaced by concise, measurable training objectives.

See the "Safety Training Definitions" section earlier in this section.

2. Illustrations should be legible and clear. Avoid photocopies when possible. Also, put illustrations on separate pages that may be folded out and reviewed while the student reads the text. Nothing detracts more than flipping back and forth from text to illustration.

3. Students should have copies of all visual aids used by the instructor.

4. Laboratories should have lab booklets that clearly define the lab objectives and have all required information at the students' fingertips.

5. Avoid using manufacturer's instruction literature for texts. While these types of documents make excellent reference books, they are not designed for training purposes.

Instructors. No one has really defined what makes the difference between a good instructor and a mediocre one. Some of the most technically qualified individuals make poor instructors while others are excellent. Some excellent public speakers are very poor instructors, while others are quite good. A few points are common to all good instructors.

1. Good instructors earn the respect of their students by being honest with them. No student expects an instructor to know everything there is to know about a subject.

An instructor who admits that he or she does not know has taken a giant step toward earning respect.

2. Instructors must have field experience in the area they are teaching. Learning a subject from a textbook or an instruction manual does not provide sufficient depth. (unless, of course, the material is theoretical.)

3. Instructors must be given adequate time to prepare for a presentation. Telling an instructor on Friday that a course needs to be taught on the following Monday will lead to poor training. Even a course an instructor has taught many times before should be thoroughly reviewed before each session.

4. Avoid using a student's supervisor for the instructor. Supervisors will often expect the student to learn because they are the supervisor. In addition, the student may feel uncomfortable asking questions.

Frequency of Training. How often to train is an extremely complex problem. Management must balance the often-conflicting requirements of production schedules, budgetary constraints, insurance regulations, union contracts, and common sense with the needs of employees to know what they are doing.

Overshadowing all this, however, is one basic fact-the employee who is not learning is moving backward. Technology, standards, and regulations are changing constantly; therefore, employees must be trained constantly. In general, the following points can be made:

1. Employees in technical positions should be constantly engaged in a training program.

Two or even three short courses per year are not unreasonable or unwarranted. The courses should be intensive and related directly to the job requirements of the employee.

2. Employee training should be scheduled strategically to occur before job requirements.

In other words, an employee charged with cable testing during an outage should go to a cable testing school a few weeks prior to the outage. Few of us can remember a complex technical procedure for two or three years.

3. Training should be provided at least as often as required by regulatory requirements.

Remember that standards and regulations only call out minimum requirements.

4. Regulatory requirements must be met. For example, OSHA rules require annual review of lockout-tagout. Training is required if problems are noted.

Element 2: on-the-Job t raining (OJT)

On-the-job training is discussed in great detail in a later section. Regarding the elements of laboratories, instructors, materials, and frequency of training, virtually all the previous discussion applies to on-the-job training, with the following additions:

1. The laboratory for OJT is the whole plant or facility. The student learns while actually on the job.

2. In OJT, the supervisor (if technically qualified) is often the most logical choice for an instructor. In this role, however, the instructor does not usually get involved in a direct one-on-one training session. Rather, the instructor gives the student the objectives for each OJT session and then evaluates progress. Note: Throughout industry we are seeing more and more multicraft shops that are supervised by nonelectrical people, such as mechanics or pipe fitters; therefore, the supervisor should not be the instructor for electrical classroom instruction or on-the-job-training.

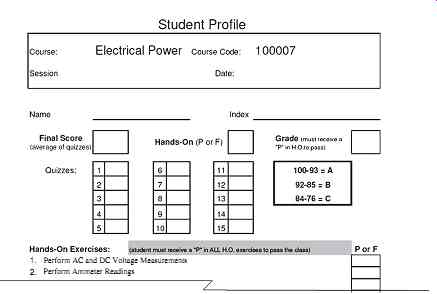

3. Good training is done on purpose. A complete training program will have OJT materials that include objectives, reading materials, and examples of what is to be done. In addition, the student should have a record card (see FIG. 1) (sometimes called a qualcard in the military) that identifies each area of responsibility. When the student has performed satisfactorily, the instructor checks off on the card to indicate successful completion.

4. Since employees are on the job every day, they are (theoretically) learning every day.

This is not true, however, of OJT. Remember that all good training is done on purpose.

Typically a student should be given one specific OJT assignment at least once per week.

An instructor (qualified person) should observe the successful completion of the assignment, and the employee should be given credit for the job.

FIG. 1 A student qualification sheet.

Element 3: Self-training

Most well-intentioned self-training fails simply because it is not organized. Adults must know what is expected before they can perform. In this sense, then, self-training has much in common with OJT, and virtually all the comments that apply to OJT also apply to self-training.

The most important element of self-training is materials. The materials for self-training must be written very carefully. Small, self-supporting modules that are prefaced with clear objectives should serve as the core for self-training materials. Each module should end with a self-progress quiz. After the student completes each module or related group of modules, the instructor should administer an examination.

Conclusion

When confronted with requirements for training, such as those previously outlined, many companies are staggered by what appears to be a very expensive investment. The investment made in training is returned many times over in improved safety, morale, and productivity.

Furthermore, a training program that does not have the proper elements will probably not be good training, and poor training is worse than no training at all.

| Top of Page | PREV. | NEXT | Index |