STEREO REVIEW'S SELECTION OF RECORDINGS OF SPECIAL MERIT--BEST OF THE MONTH

--- CLASSICAL ---

PIANO DUETS BY DEBUSSY AND RAVEL--Alfons and Aloys Kontarsky present some unusual French repertoire.

ONE tends to think of the piano-duet tradition as essentially Central European and just a little old-hat. A new Deutsche Grammophon release comes as a double surprise, therefore, for it not only reminds us that two French composers, Debussy and Ravel, made some major contributions in the genre, but it does so with the superbly realized performances of two German pianists previously noted principally for their strong avant-garde connections.

Since there is sometimes a lingering audience suspicion (not without foundation) about the stylistic and even textual scrupulosity of avant-garde per formers, let me emphasize first of all that these are remarkably sensitive performances: idiomatic, with fine poetic feeling, full of color and nuance, and always with proper attention paid to the larger musical values.

But there are times when one has to wish that the Germans were not so damned thorough.

- CLAUDE DEBUSSY---- The show and the substance.

We certainly could have done without the Debussy Symphony in B Minor here, an obvious piece of juvenilia that can be nothing more than a sketch in two-piano form anyway. The two-piano versions of the Prelude a l'apres-midi d'un faune, for that matter, is hardly a must either. (Orchestral performance in France being what it was--and still is--Durand, the publisher of both Debussy and Ravel, put out virtually everything in two-piano and one-piano-four-hands editions designed to appeal to the cultivated amateur. If nothing else, these arrangements do at least give the lie to the old canard that the music of Ravel and Debussy is all coloristic show and no substance.) On the other hand, the exquisite four-hand version of Ravel's Mother Goose (Ma Mere l'Oye) is the original, and so is the Debussy Petite Suite. And En blanc et noir (a piano piece is to an orchestral work as a black and white pen or pencil sketch is to a painting) is one of the most remarkable works of Debussy's last years.

Among the smaller, little-known works, there is at least one delightful novelty: Ravel's Frontispice is as far out and enigmatic a piece of music as one could expect to find any where, any time in the first half of this century; if nothing else, it is at least a remarkable musical curiosity.

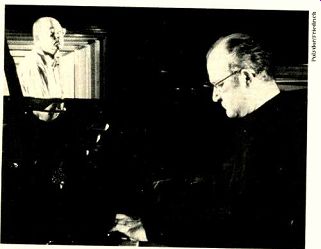

----- ALFONS AND ALOYS KONTARSKY: idiomatic performances.

I cannot imagine anything better realized, either musically or technically, than these two splendid discs; they are impressive for the best of all possible reasons--for their beauty, for their justice to the music they present, and for the communicative values they have discovered in it. The piano sound, moreover, is first rate in both its quality and its recorded "presence." The disc surfaces, finally, are astonishingly quiet even by Deutsche Grammophon's own high standards. If you have been bashful up to now about broadening your acquaintance with French music, content with La Mer and Clair de lune on the one hand, with Bolero and La Valse on the other, these recordings are, at least for this month, the best possible place to start changing all that. Eric Salzman DEBUSSY: En blanc et noir; Petite Suite; Lindaraja; Cortege et air de danse; Ballade; Six Epigraphes antiques; Symphonie en si mineur; Marche ecossaise; Prelude a Papres-midi d'un faune.

RAVEL: Ma Mere l'Oye; Rhapsodie espagnole; Entre Cloches; Frontispice. Alfons and Aloys Kontarsky (pianos). DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2707 072 two discs $15.96.

--------------

MICHAEL TIPPETT'S THIRD SYMPHONY

Colin Davis conducts in a Philips recording that seems almost bound to be controversial.

SIR MICHAEL TIPPETT, as Music Editor James Goodfriend noted in his brief biographical appendix to Bernard Jacobson's appreciation in the March issue, is a composer whose music "cannot really be divorced from the rest of the man. His concerns with life are his musical concerns and vice versa." This is evident in his Third Symphony, completed in March 1972 after what might be regarded as a gestation period of nearly seven years.

It is the most vast of Tippett's orchestral works, one in which, perhaps more than in any other, he undertakes to make a statement about his (and our) time, in words (his own) as well as in music.

As can be discovered in Philips' new recording of the work (Colin Davis leading the London Symphony Orchestra), Stravinskian principles are involved, Beethoven is quoted, and the jazz and blues that have fascinated Tippett since his youth are brought into play with unselfconscious effectiveness.

The two huge sections of the work break down into subsections corresponding to the four movements of a conventional symphony, the first part brooding and introspective to an almost painful degree, and the final section constituting a reaction-one almost wants to say rebuttal-to the Schiller ode set by Beethoven in the finale of his Ninth.

Tippett uses the opening of the Beethoven finale to introduce his own, and again to separate its epi sodes, but instead of a chorus he has written a blues sequence, for solo soprano, more or less in the style (as Colin Davis was first to observe) of a latter-day William Blake. Their burden is that instead of the milk and honey of brotherhood promised by Schiller/Beethoven, we have tasted the wormwood and gall of monstrous inhumanity. If some portions of the text seem rather less pertinent than others ("O, I'll go whirling/with my armpits glist'ning/and my breast-buds shaking ... "), it is simply that the metaphors of the earlier blues sections relate to the ages of a human being. The third song deals with injustices such as would make one question the idea of the "loving Father" hymned by Schiller/ Beethoven- a dwarf, a "girl born dumb and blind" (Helen Keller)--and in the last we have the direct confrontation with the Ninth, in lines whose unstrained simplicity recalls Tippett's earlier A Child of Our Time:

They sang that when she waved her wings

The Goddess Joy would make us one.

And did my brother die of frost-bite in the camp?

And was my sister charred to cinders in the oven?

We know not so much joy far so much sorrow. . . .

At the end, though, beginning with a phrase from Martin Luther King, Tippett makes his own paradoxical statement of affirmation, proclamative and heartening:

I have a dream, that my strong hand shall grip the cruel, that my strong mouth shall kiss the fearful, that my strong arms shall lift the lame, and on my giant legs we'll whirl our way over the visionary earth in mutual celebration. . . .

From all this one might gather that the Symphony has elements in common with such works as Berio's Sinfonia and Bernstein's Mass-and so it does: quotation, topicality, the incorporation of jazz and blues. But it has a far more strictly organized form, conveying a stricter sense of purpose, and, despite the jazz and blues, despite the allusions to Bessie Smith and Stravinsky and Beethoven, this is not pastiche but, as always with Tippett, a highly original and deeply felt expression in which no amount of "influences" (whose presence Tippett himself is the first to acknowledge) can diminish or mask his own individuality. He might well say of his Third, as Sibelius did of his own Fourth Symphony: "There is nothing, absolutely nothing, of the circus about it." It is a hugely subjective piece (what old timers would call "strong medicine"), and it is more than likely that no two listeners will respond to it in exactly the same way; the one reaction I cannot imagine is indifference.

A matter clearly beyond the bounds of subjective reaction is the extraordinary performance (under the auspices of the Swiss-based Rupert Foundation) by the Artists (the capital "A" is little enough in the way of tribute) who gave the Symphony's premiere in June 1972. There are prodigious demands on the soprano, and on the orchestra too, but so successfully are they met that the listener is aware of nothing but the impact of the music itself.

The performance, rooted in something much deeper then mere virtuosity, is magnificent, totally and in every detail; it is alive with conviction. The Philips engineers, no less inspired than Davis, Harper, and the rest, have come through with what may be the finest orchestral sound yet achieved on this label. Unquestionably this is one of the major releases of the decade.

--Richard Freed

TIPPETT: Symphony No. 3. Heather Harper (soprano); London Symphony Orchestra, Colin Davis cond. PHILIPS 6500 662 $6.98.

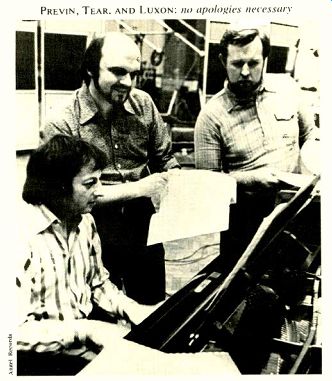

-- PREVIN, TEAR, AND LUXON: no apologies necessary.

--------------------

SOME VERY LATE VICTORIANS

Making it clear that, whatever else it is, Come into the Garden Maud is not a joke.

GET yourself a potted palm and a high-backed chair, close your eyes, and let three of the cleverest musicians in England-tenor Robert Tear, baritone Benjamin Luxon, and that wizard of baton and keyboard Andre Previn--transport you to a Victorian salon for a song recital worthy of the un divided attention of the Queen who gave her name to a much-maligned-and now much-regretted-age.

Victorian parlor songs were generally watered wine drawn from bottles labeled Donizetti, Bellini, Rossini, and such, but anyone who has ever attended a performance of Cox and Box or The Sorcerer will recognize the home-grown bouquet of the music of Sir Arthur Sullivan as well. In fact, the little musicale just now offered for our delectation by Angel Records begins with The Dicky Bird and the Owl, a setting by Sullivan of a lyric by Sinclair that traveled almost intact to the score of Cox and Box as The Buttercup ("I come by night, I come by day . . .). It makes a charming opener.

There inevitably follow those songs about brave men doing their duty, the moon raising her lamp, the rescue of little storm-tossed travelers by heavenly (I suppose one should say heav'nly) intervention, and other themes dear to Victorian hearts. There's a setting by some forgotten fellow named Leslie of Poe's Annabelle Lee that is surprisingly touching, two songs by Balfe (he who wrote that operetta favorite of grandmother's called The Bohemian Girl) to texts by Tennyson (you remember Come into the Garden, Maud) and Longfellow (Excelsior), and even a ballad about an Arab's heartfelt speech of farewell-to his horse. You will not easily forget a little puff of melodic smoke called Cigarette, nor, certainly, the concert's conclusion: The Gen darmes' Duet, by Offenbach, a tune that is the original of our Marine Corps Hymn ("From the halls of Montezuma . . .").

Yet, for all the Gothic atmosphere of the lyrics, the manacled skeletons in the closets, and the blue eyed zealots carrying banners labeled "Excelsior" across the Alps, there is really nothing here, in musical terms, to patronize. As Robert Tear points out in his notes, "these songs are not amusing museum relics but as full of lovely melody and grand sentiment as pertinent to their age as were Dowland and Monteverdi's music to theirs." Indeed, as Mr. Tear and Mr. Luxon sing them to Mr. Previn's incisive accompaniments, the songs more than hold their own, and the program needs no apology. On the contrary, Tear himself, who thought up the whole concert, should be thanked heartily for a labor of love performed free of condescension and in splendid style. And, having gotten your feet wet in this seductive repertoire, you may want to get in a little deeper with an Argo album called "Music All Powerful (To Entertain Queen Victoria)," ZRG 596. It contains, among other treasures, a song by the Queen's Consort, Albert, Prince of Saxe, Coburg, and Gotha, as well as a moving solo for the ophicleide (q.v.).

-Paul Kresh

VICTORIAN SONGS. The Dicky Bird and the Owl; The Trumpeter; Annabelle Lee; Cigarette; Tom Bowling; Saved from the Deep; The Moon Has Raised Her Lamp Above; Excelsior; Come into the Garden, Maud; The Arab's Fare well to His Favorite Steed; The Lark Now Leaves His Wat'ry Nest; The Death of Nelson; The Gendarmes' Duet.

Robert Tear (tenor); Benjamin Luxon (baritone); Andre Previn (piano) ANGEL S-36975 $5.98.

--------------

--- POPULAR ---

CLEO LAINE LIVE!!! AT CARNEGIE HALL

A sizzling new album from RCA will commend her to an even larger international audience.

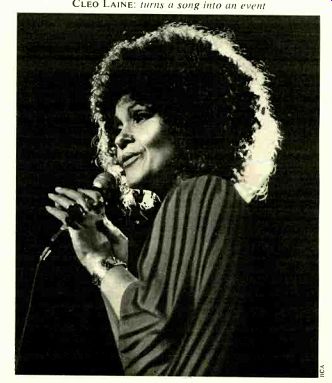

WHO is Cleo? What is she? Her swains at the vl V London Sunday Times have called this lady with the modified Afro and the big blue eyes "quite possibly the best singer in the world." And quite possibly she is. I know she is the only singer in the world I would stay up to watch on the Johnny Carson show. She is possessed in abundance of the three "s's" essential to the success of any songbird:

sex appeal, sophistication, and sizzle. With a working range of four octaves, the ability to turn any song she tackles into an event, and a talented husband (John Dankworth, a whiz at conducting, arranging, and composing popular music as well as playing it on saxophone and clarinet) to encourage her, she has built up an increasingly frenzied throng of admirers on both sides of the Atlantic.

The vitality, virtuosity, and range displayed in her latest album, artfully assembled by RCA from a landmark concert she gave at New York's Carnegie Hall last October, seem to me to justify all three of the exclamation points in its title. The concert begins-and ends-with a wistful a cappella treatment of the folk song / Know Where I'm Going which leaves no doubt in one's mind that Cleo LaMe does, indeed, know where she's going and how to get there as well. No two of the numbers in between these winning bookends are alike in spirit, context, tempo, or mood, yet all bear the unmistakable imprint of her inimitable singing style. Not the least of Cleo's virtues is her ability to gallop back and forth across the so-called generation gap-for first-class talents such as hers it has never existed anyway--bringing off folk, blues, and torch songs of the past one moment and demonstrating how a worthy contemporary song such as Stop and Smell the Roses should be sung the next.

It is hard to pick, out of this brimming cornucopia of delights, anything one might call a "favorite," but it is even harder to refrain from mentioning, say, Gimme a Pig Foot and a Bottle of Beer (better, I think, then Bessie Smith's original), Control Your self (practically an entire musical comedy all by it self), and Stephen Sondheim's Send in the Clowns from A Little Night Music (Cleo has found depths in it that neither Glynnis Johns nor Renata Scotto she has sung it in concert-nor even Frank "Ol' Blue Eyes" Sinatra has plumbed).

------- CLEO LAINE: turns a song into an event,

After ploughing through so much unabashed adulation, those almost-persuaded readers who are still with me might well be wondering whether I don't have at least one little reservation about this record in what is left of my blown mind. Well, yes, there are two: first, I find myself wishing at times that Miss Laine would succumb less often to the urge to imitate her husband's saxophone and other musical instruments, and second, that RCA's engineers had been a mite less generous with audience noises-grunts, groans, gasps, and, to be sure, lots of applause. But these are merely druthers; you won't get me to admit that this album has any flaws!

- Paul Kresh

CLEO LAINE: Live!!! at Carnegie Hall. Cleo Laine (vocals); John Dankworth (clarinet and saxophone); Anthony Hymas (piano and electric piano); Daryl Runswick (Fender bass and upright bass); Carmine D'Amico (guitar); Graham Morgan (drums); John Dankworth arr. and cond. Intro; I Know Where I'm Going; Music; Wish You Were Here (I Do Miss You); Gimme a Pig Foot and a Bottle of Beer: You Must Believe in Spring; Perdido; Control Yourself; Send in the Clowns; Ridin' High; Bill; Big Best Shoes; Stop and Smell the Roses; Please Don't Talk About Me When I'm Gone. RCA LPL1-5015 $5.98, LPSI-5015 $6.98, LPKI-5015 $6.98.

------ GOLDEN AGE ECHOES: BIG STAR ------

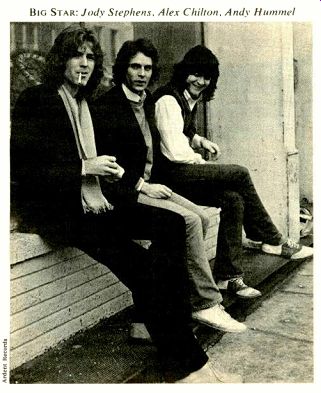

------ BIG STAR: Jody Stephens, Alex Chilton, Andy Hammel.

Their new " Radio City" for Ardent reveals them as unabashed students of the Beatles IT'S a fact of life, here in 1974, that everybody misses the Beatles. I miss them, you miss them, misses them, and, more important, artists like Blue Ash, Stories, Badfinger, and the Raspberries miss them-so much so, in fact, that they've taken to making records on which they pre tend to be the Beatles. One's reaction to this sincerest form of flattery depends, as some critics have pointed out, on whether or not you think it displays a marked lack of originality or is merely a legitimate attempt to work within an established genre. But despite the fact that I really like some of this ersatz-- Liverpool stuff (especially such recent Raspberries efforts as Tonight), there's an air of self-conscious ness about even the best of it that largely spoils it for me.. It's all, somehow, too clever for its own good, as are the earnest appeals to an imagined Teenage Consciousness that it all too often comes couched in.

Which is why Big Star's very unselfconscious second album on Ardent, "Radio City," is such an unabashed delight The songs are as unforced and natural sounding as the models they're based on, and when the band does get down to the kind of naïve, adolescent love songs that you really haven't heard in years, for a change you believe the sentiments expressed. There's real feeling in them.

Alex Chilton, the band's lead singer and writer, is a remarkable character. In the late Sixties, still a teenager, he sang, in an extremely gruff, Southern, r-&-b style, with a group called the Boxtops. It seems, however, that all the while he was aping Ray Charles on records, he was at home trying to sing like Paul McCartney and play guitar like Jim Mc-Guinn. That's roughly where he's at now, as a listen to the album's standout tracks, September Gurls and Back of a Car, will demonstrate. But all the songs on "Radio City" are cut from similar cloth--in other words, from the kind of melodic, atmospheric pop music that groups like the Zombies, the Beach Boys, and the Who were making in 1966-and they're almost all first rate. And as if that weren't enough, the album is recorded in a deliberately anachronistic way (some of it is even in mono, Phil Spector will be happy to learn), and the effects reinforce the impression one assumes Chilton was trying to make-that these are previously undiscovered masters by a superb, unknown group from that warmly remembered Golden Age.

I didn't care for the band's first record, which was much slicker and more contemporary in feeling, but with this new one I'm beginning to think that some of the incredibly exaggerated claims made for them have a basis in fact. Of course, whether or not Chilton and his co-workers can sustain this level of excellence is open to question, but " Radio City" is a knockout album, and you miss it at your peril.

-- Steve Simels

BIG STAR: Radio City. Alex Chilton (guitar and vocals); Andy Hummel (bass); Jody Stephens (drums). O My Soul; Life Is White; Way Out West; What's Going Ahn; You Get What You Deserve; Mod Lang; Back of a Car; Daisy Glaze; She's a Mover; September Curls; Morpha Too; I'm in Love with a Girl. ARDENT ADS 1501.

+++++++++

----------

Also see: