Stereo Review presents the twenty-first article in the American Composers Series

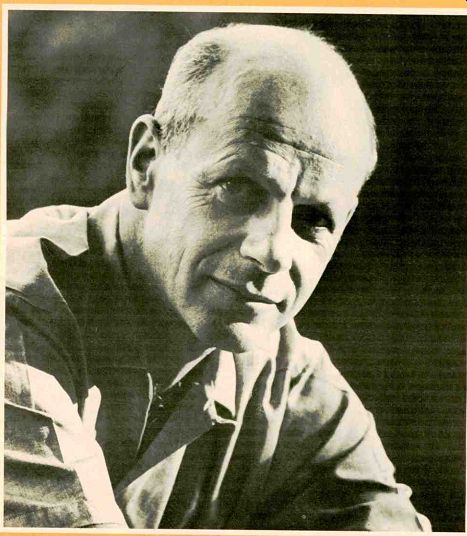

WILLIAM SCHUMAN -- "I've got to be a musician ... My life has to be in music."

By SHEILA KEATS

THE audience clearly belonged to the "now" generation. Luxuriant of beard and of hair, peering through the latest in "Granny" glasses, the young men gathered together in the Waldorf-Astoria ballroom were casually dressed in jeans, open shirts, and psychedelic trappings. What brought them to the Waldorf rather than to, say, a concert at the then-refulgent Fillmore East was the annual presentation ceremonies of Broadcast Music Incorporated's Awards for Young Composers.

And there to address this audience of young-composer hopefuls was the tall, debonair, and impeccably groomed speaker of the evening. Surveying the group, he opened with a greeting: "Welcome to the Establishment." The speaker was composer William Schuman, and his unorthodox opening was typical. For the swift parry, the ready riposte, the disarming challenge--all delivered with a note of humor--are trademarks of the man. So is honest self-appraisal. To most young composers, and to much of the public at large, Schuman represents the musical Establishment, a role assignment he cheerfully accepts. He has never swelled the ranks of the protesters, never taken a radical stance in order to gain attention, never attempted to pursue his career or promote his mu sic through social or professional shock tactics. A missionary for music who has served the cause as teacher, editor, executive. and composer, he has always preferred to work within the system rather than to attack it from without.

William Howard Schuman was born August 4, 1910, in New York City. The second child in the family (he has an older sister, Audrey), he was named in honor of William Howard Taft. then President of the United States. His Father, who had simplified the spelling of the family name from the was an executive with a New York City printing firm.

Schuman managed to construct (it was easier then than it is now) an all-American boyhood on New York's upper West side, a rather carefree life devoted to, if anything, sports. "Baseball was my youth," he says, and he has never lost his enthusiasm for the sport. While still in grade school he organized an outing club in which he taught boxing, wrestling, and baseball to the neighbor hood children for a fee of fifteen dollars a month. The club met daily after school and all day on Saturday: its success was early evidence of Schuman's organizational ability and salesmanship.

Music played only a casual role in his life in those days.

Pre-radio and pre-television, the Schuman family, like many others, enjoyed Sunday evening sessions around the piano. In reminiscing for a group of Friends of the New York Philharmonic, Schuman recalled: "It was a typical middle-class background. We would sing at home-Victor Herbert, show tunes, winding up with a light classic like Welcome, Sweet Springtime. We also had a Victrola, and would listen to Caruso and Zimbalist records. For a time, my father even played the William Tell Overture on the Pianola every morning before going to work." Out of a desire to play Beethoven's Minuet in G, the height of his musical ambitions at the time, Schuman re quested violin lessons, which he began at the age of eleven. When he got to high school, he shifted briefly to the double bass. "The school needed a bass player for the orchestra, so they gave me an instrument, a room, and a self-instruction book. By the end of the year I was playing in a contest for New York City school orchestras. In fact, since I was the only bass player in the New York City schools, I played in every one of the orchestras, doing nineteen performances in a row of the Oberon Overture.

The truth of the matter is that I can't play any instrument well. But since I couldn't play any one well. I learned to play several badly. I tried the piano, the banjo, the saxophone, and the clarinet (which I got from a hock shop), and of course the violin.

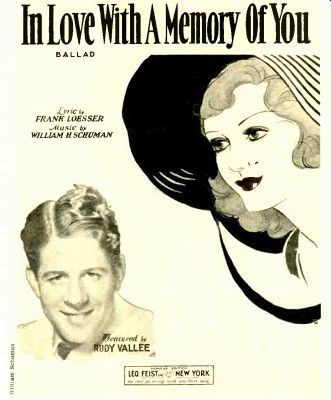

"In high school I formed a jazz band. 'Billy Schuman and his Alamo Society Orchestra.' I sang with the band and played in it--and also acted as business manager. We played at weddings, bar mitzvahs. proms, and were really quite successful. I also made arrangements for the band, even though I had no real knowledge of music. I didn't even know how to write out a score, so I taught the players their parts by rote. During the summers, at camp. I wrote musical shows and songs. Several of the songs were even published." Schuman's principal collaborator was Frank Loesser.

with whom he turned out a large number of popular songs and special material for vaudeville, usually with lyrics by Loesser and music by Schuman. Loesser's first published song, with music by Schuman. was called In Love with the Memory of You. According to Schuman it was one of Loesser's few flops.

All of this, however, was strictly extracurricular. Schuman, who had transferred from Manhattan's P.S. 165 to the Speyer Experimental Junior High School for Boys, a school for superior students, graduated in February of 1928 from George Washington High School. Al though musical activities were already taking up a good bit of his time, it did not occur to him that music should be his profession. Business seemed the logical goal, and he registered at the New York University School of Commerce to prepare for a career in advertising. On the side, he did some playing in night clubs, wrote copy for an advertising agency, and worked as a printing salesman.

IT took Schuman two more years to discover his true vocation. "My sister inveigled me into going to a Philharmonic concert with her. The friend she usually went with was sick, and she didn't want to go alone. I went really as a favor to her-but that concert literally changed my life.

I still remember the date: April 4, 1930. I was astounded at seeing that sea of stringed instruments, and everybody bowing together. The visual thing alone was astonishing.

But the sound! I was overwhelmed: I had never heard anything like it. The next day I withdrew from N.Y.U. I left N.Y.U. and started to walk home from 4th Street to 112th Street. As I walked, I thought and thought about all those wonderful sounds. 'I've got to be a musician,' I thought. 'My life has to be in music.' All those sounds were still going 'round and 'round in my head. As I passed 78th Street and West End Avenue, I noticed a sign on a private house: Malkin Conservatory of Music. I walked in and said: 'I want to be a composer. What should I do?' The woman at the desk said promptly:

'Take harmony lessons.' So I signed up to study harmony with Max Persin." Persin. who had been a student of Anton Arensky, was apparently both an inspiring and a thorough teacher, one who insisted that his students study scores as well as exe cute exercises. Together he and Schuman went through reams of music, placing a strong emphasis on contemporary works. Harmony lessons with Persin were later supplemented by a course in counterpoint with Charles

------

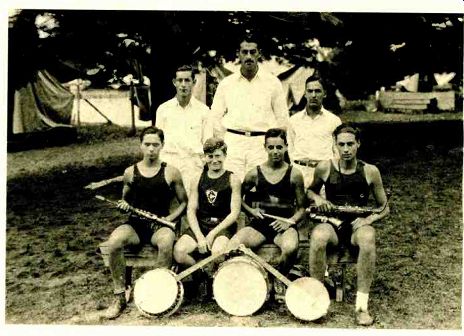

----------- Music at Camp Cobbossee: Schuman, seated third from the left with the violin, also doubled on banjo, and provided the music for the camp shows.

Haubiel. Before he was through, Schuman could write a fugue in fourteen voices.

But he was still flirting with Tin Pan Alley, writing popular songs, doing a little song-plugging, and making arrangements for jazz bands. "The orchestra interested me, but no one had told me about a conductor's score. I would spread music sheets all over the floor of my work room, one for each player, and write each part out of my head. Then I'd take the parts to a jazz band playing in a basement joint at Columbus Circle and, by bribing the players with cigarettes, get them to try out the parts so I could hear them. Later I worked with the band at the Biltmore; they would try out my arrangements in the kitchen during breaks." It was a novel way of learning the trade, but one which nonetheless gave him a very clear grasp of the practical possibilities of the orchestra. It also reinforced his conviction that, for him at least, jazz and symphony do not mix. He made his choice, and Tin Pan Alley lost.

At twenty-two, Schuman went back to college, enrolling in Columbia University's Teachers College. "I could have gone to Hollywood with Frank Loesser, but I knew I had to work for a career in serious music. I wanted to teach, and I also wanted a normal, rich, personal and family life. In short, I wanted to be my own patron." Schuman neither particularly enjoyed nor approved of the Teachers College approach to music and music education, for his is too free-wheeling a mind to confine itself to rigid methods or standard curricula. But his years at Teachers College were to prove fruitful later, for his experiences there led him to formulate his ideas on how music could most effectively be taught.

"Five years after that Philharmonic concert with my sister, I was teaching music at Sarah Lawrence College. I was asked to give a course in the performing arts, al though we didn't use the term then. How do you bring people to the arts? How do you teach them? Start right with the materials. The first assignment I gave in music was: listen to ten hours of music before next week's class, and try to hear at least twenty pieces. The idea was to plunge right in, get the sounds in their heads. When the class met again, I asked the students to give me their lists of the pieces they had heard. Interestingly enough, almost every one had picked, as one of her twenty pieces, the Brahms Second Symphony. So we started with that. We took each movement, discussed it from every viewpoint we could think of: mood, texture, dynamics, melody (we sang the melodies), rhythm (we tapped out the rhythms), instrumentation, form. By the time we were through, the students really knew something about the work, and something about Brahms.

When Schuman arrived at Sarah Lawrence, he was still a relatively untried and inexperienced composer. He knew something about popular music, and he had harmonic and contrapuntal technique to burn; but he was yet to be recognized as a serious composer of a major work.

During the summer of 1935, in Salzburg, he had worked on his First Symphony, scored for eighteen instruments.

The following summer he took it to Roy Harris. Harris did not think the work terribly good, but he saw potential in it. "I went to Harris on purpose, because I had heard his Symphony 1933 [Symphony No. 1]. I thought it was marvelous, and still do. Harris was producing some of the most original music written by an American composer; I was tremendously impressed by its strength and originality. Harris was a tremendous influence on me." In the fall of 1936, Schuman's First Symphony was performed at a WPA Composers' Forum Laboratory concert. "Even to my excited ears, it was disappointing," he recalls. "I withdrew it." The following year Schuman completed his Second Symphony, submitting it to a competition whose jury included Aaron Copland. The work was performed in June of 1938 by Edgar Schenkman and the Greenwich Orchestra, and shortly after was broadcast by the CBS Orchestra under Howard Barlow. Copland, who had been impressed with the score, heard both performances, and recommended the work to Serge Koussevitzky. "It was Copland." Schuman says, "who gave me practical help: getting performances." Copland also introduced Schuman in the pages of Modern Music. In the May-June 1938 issue he wrote: "Schuman is, so far as I am concerned, the musical find of the year . . . a composer who is going places." Koussevitzky accepted the Second Symphony, per forming it in Boston in February of 1939. As Schuman tells it, "It was hissed." Obviously the work was too advanced for Boston. "Nobody today among the avant garde would believe that I wrote a work good enough to be hissed," says Schuman. Koussevitzky, however, had faith in the young composer, and a young Harvard student, one of the few people in the audience who applauded, asked to see the score. It was the beginning of the long friendship between Schuman and Leonard Bernstein.

During the summer of 1939 Schuman worked on a short orchestral piece, the American Festival Overture, which he hoped Koussevitzky would include in the festival of American music he was planning for the fall. Koussevitzky did accept the overture, first performing it on October 6, 1939. It became an immediate success. Bold, brassy, full of youthful self-confidence, it has lost none of its freshness or appeal over the years. Its "Americanism" stems from the opening three-note motif, out of which the entire piece grows. Schuman's own program note explains the derivation:

The first three notes of this piece will be recognized by some listeners as the "call to play" of boyhood days. In New York City it is yelled on the syllables "Wee-Awk-Eee" to get the gang together for a game or a festive occasion of some sort. This call very naturally suggested itself for a piece of music being com posed for a very festive occasion. From this it should not be inferred that the Overture is program music. In fact, the idea for the music came to my mind before the origin of the theme was recalled. The development of this bit of "folk material," then, is along purely musical lines.

--------------------

Schuman was not one of Frank Loesser's "chief collaborators," but they wrote together until each went on to better things.

----------------------------

WTH the American Festival Overture, Schuman hit his stride. Two years later he solidified his position on the American musical scene with his Symphony No. 3, introduced by Serge Koussevitzky and the Boston Symphony Orchestra on October 17, 1941. This time Boston liked Schuman, and when Koussevitzky repeated the work five days later in New York, Olin Downes gave it a rave review in the New York Times:

The concert of the Boston Symphony Orchestra yesterday afternoon in Carnegie Hall introduced to the public of this city the Third Symphony of young Mr. William Schumann [sic], a symphony which, for this chronicler, takes the position of the best work by an American of the rising generation that he has heard. . . . this symphony is full of talent and vitality, from first to last, and it is done with an exuberance and conviction on the part of the composer that carry straight over the footlights and sweep the listener along in their train ....

Like the American Festival Overture, the Symphony No. 3 revels in its moments of brashness, its aura of energy and youthful confidence, its delight in rhythmic excitement and instrumental brilliance. Schuman himself, who has grown a little tired of the charge that he writes only "loud" music, must have been pleased that Downes praised the symphony's "lyric substance" and "vistas of harmonic as well as linear beauty." Its structure pays direct obeisance to the sixteenth-century forms Schuman admires. It is in two sections, the first a passacaglia and fugue, the second a chorale and toccata. Schuman fills out these forms with thoroughly contemporary melodies, harmonies, and rhythms. Both brilliant and moving, the Symphony No. 3 has remained a favorite work in the repertoire, and one that is frequently performed. While sacrificing none of the immediacy of the American Festival Overture, it reveals a growing subtlety and sophistication on the part of the composer. At the end of the 1941-1942 season, it was chosen by the Music Critics' Circle of New York for their first annual award "for the best new American orchestral work performed in New York during the current season." The Symphony No. 4, completed during the summer of 1941, was introduced by Artur Rodzinski and the Cleve land Orchestra. Unlike the Third Symphony, it is cast in a more traditional three-movement, fast-slow-fast structure. Basically linear in concept, it achieves an effective balance between that rhythmic and instrumental exuberance so characteristic of Schuman and a tender lyricism just then beginning to emerge in his music. The restless urgency and nervous drive are here tempered, and Schuman even relaxes enough to introduce moments of jaunty insouciance in contrast to the more insistent, dramatic passages.

Much of Schuman's composition during these same years was for chorus. Many of the choral pieces were in tended, of course, for the choral group he led at Sarah Lawrence; his practical experience there is reflected in his sure and easy handling of the medium. Schuman, in fact, is one of the few contemporary composers with a real gift for vocal writing. He treats the voice with both sympathy and understanding; his lines lie comfortably within the range and they move easily. He knows how to expose the voice to best advantage. Even individually, his choral lines are always satisfying; in combination, they produce effective massed sonorities. As always, Schuman writes music that sounds. He is sensitive to his texts, underscoring the emotional content with the mood of the music. His prosody is notable, whether he sets the text in a rhythm paralleling the word rhythms, or chooses to create subtle cross-rhythms between words and music.

The Symphony for Strings (Symphony No. 5), commissioned by the Koussevitzky Music Foundation, dates from 1943. It is one of Schuman's most original and at tractive works. Deliberately denying himself the easy road to brilliance provided by winds, brass, and percussion, Schuman relies on his musical materials alone to create variety and drama within the context of a string orchestra. Exploiting to the full the strings' generic lyric possibilities, he writes long singing lines which stand out in relief from the imaginative rhythmic and percussive passages. Schuman's linear approach is ideally suited to the string group, and he is extremely imaginative in his demands for a variety of sonorities. The pizzicato scoring in the bright finale as well as the passages for cheerfully rumbling basses deserve special mention.

The years between the American Festival Overture and the Symphony for Strings saw the composition of a number of smaller works. There was the Quartettino for Bassoons and, in response to his first commission, the Third String Quartet. There were two secular cantatas, the second of which, A Free Song, was awarded the first Pulitzer Prize for Music. There was the Piano Concerto, and the eloquent orchestral Prayer in Time of War. The Symphony for Strings was followed by two short works written to texts from Shakespeare's Henry V III, the solo song Orpheus with His Lute, and the brilliant a cappella chorus, Te Deum. There was his first film score, Steel-town, commissioned by the Office of War Information, and a brief reversion to Broadway with the Circus Over ture (Side Show), a bit of musical high jinks commissioned by Billy Rose for his revue, The Seven Lively Arts.

By this time Schuman was beginning to be restless under the demands of his heavy teaching-conducting-composing schedule. Since 1938, he had enjoyed extremely cordial relations with the music-publishing house of G. Schirmer, as well as a warm friendship with its president, Carl Engel. Engel, thoroughly enthusiastic over the choral works Schuman had submitted to him, and one of the Third Symphony's most ardent supporters, had re quested first refusal on everything Schuman wrote. By 1944, Schirmer was publishing everything Schuman submitted. When Engel died suddenly in May of 1944, Schirmer's, on the advice of Koussevitzky, offered Schuman the post of director of publications. It was an ideal opportunity: an interesting job in itself, an assured regular income, and plenty of time to compose. It was with some what mixed feelings that Schuman resigned his post at Sarah Lawrence-he had found great pleasure, stimulation, and satisfaction there-and settled down to a three year contract with Schirmer's.

Schuman's major compositional effort that year (1945) was Undertow, his first work for the theater, commissioned by the Ballet Theater and choreographed by Antony Tudor. Powerful and moving, it is a dark drama of degradation and corruption, culminating in murder. Schuman's score is full of tension: rhythms here produce apprehension, climaxes are sharp and brutal, and the short, contrasting sections appear in stark succession, often without benefit of transition.

--------- Schuman teaching a music class at Sarah Lawrence College: "The

idea was to plunge right in, get the sounds in their heads."

The reflective, intellectual life Schuman had mapped out for himself was not to last. Had he been as wise or as experienced as he is now, he would have realized, man of action that he is, that his own energies and vital interest in affairs would not permit him to remain con fined to his study or his editor's chair for very long. A pair of coincidences brought him to the attention of the Board of the Juilliard School, then in the market for a new president. Kay Warburg, daughter of Juilliard Board member James P. Warburg, had been a member of Schuman's Sarah Lawrence chorus, and had more than once enlivened the family dinner table with glowing accounts of Sarah Lawrence's glamorous young instructor. When the search for a president for Juilliard began, Warburg inevitably thought of Schuman. Meanwhile, Schuman had accepted an invitation to participate in a panel discussion on modern music at the New School for Social Research.

Also on the panel was John Erskine, an ex-president of Juilliard and an influential member of its Board. Each of the participants was offered ten minutes for a formal presentation of his views on modern music, the formal talks to be followed by a question-and-answer session with the audience. Schuman had originally elected to give up his formal ten minutes, asking instead to have the first crack at the question-and-answer session. But when he heard Erskine state firmly that modern music has no melody, and does not communicate, he changed his mind. "I want my ten minutes back," he said-and used them to prove, by singing a goodly portion of Hindemith's Mathis der Maier, that modern music does indeed have melody.

Erskine was impressed by the young man's performance, by his passion for his subject, and by his evident wide knowledge. He was also impressed by Schuman's clear-headed ability to think on his feet and by the courage and wit he demonstrated in demolishing Erskine's own points. Separately and independently, both Erskine and Warburg approached Schuman, asking if he would be interested in being considered for the Juilliard presidency. Schuman turned them both down. "I'm not a candidate," he kept insisting. "I've just started my job at Schirmer's. I like the work, it gives me plenty of time to compose. I'm very happy where I am."

But Erskine had already brought Schuman's name up to the Juilliard Board. Franklin Benkard, a long-time Juilliard Board member, recalls those days vividly: "We had interviewed a lot of fellows. They all said about the same thing. We'd ask them, 'What would you change about the school?' and they all said, 'Nothing.' Then one day John Erskine came around and said: 'Boys, your troubles are over. I've found the guy for you. I was at the New School last night and heard this young fellow named William Schuman.' So of course we said, 'Bring him around.' "

By that time Schuman was beginning to be tempted, at least enough to meet the Board members and talk with them. "We had a little polite conversation," Benkard continues. "'Mr. Hutcheson, as you know, is about to retire.

Would you be interested in becoming president of Juilliard?' Schuman said yes, he might be interested. 'What do you think of the school?' we asked him then. 'What would you change?' He answered that if he ever did be come president, he'd change so many things that we wouldn't recognize the place. He then proceeded to talk for an hour and a half, telling us, in great detail, exactly what he would do. As it turned out, he later did every thing he had outlined for us that day."

SCHUMAN became president of Juilliard on October 1, 1945, and immediately began to translate his ideas into action. The school as he found it was in reality two schools, the Institute of Musical Art (founded by Frank Damrosch in 1905) and the Juilliard Graduate School (established in 1924 under a legacy from Augustus D. Juilliard), which since 1926 had been operating in uneasy coalition. Schuman's first move was to amalgamate the two into a single institution. It was a tricky administrative task, but the kind that always provides him a pleasurable challenge.

Schuman addressed his initial reforms not to the school's structure but rather to the repertoire being presented at its concerts. From the start, he insisted that Juilliard should lead the way in the presentation of contemporary music. During his years as president, audiences at both in-school and public concerts learned to count on a large dose of twentieth-century music, some being per formed for the first time, some already on its way to a permanent place in the repertoire. The school was receptive to all new music, whatever its style, whoever its composer. The only composer who was somewhat neglected in the programming-and that by his own choice was William Schuman.

By the time Schuman had been at Juilliard for a year, he was ready to institute his most revolutionary educational reform. This was the complete revamping of the school's theory department, which was then offering graded, separate courses in the rudiments of music--harmony, counterpoint, sight-reading, keyboard harmony, music history, form and analysis, orchestration-all ...

---------- In 1959, Schuman played host at Juilliard to a committee

of American composers: seated (left to right) are Douglas Moore and

Roger Sessions: standing, Aaron Copland, Elliott Carter, Wallingford Riegger,

Schuman, and Walter Piston.

---------- Mr. and Mrs. Schuman with Charles Munch backstage in Boston

after the premiere of the Seventh Symphony on October 21, 1960.

... taught primarily out of textbooks full of academic exercises but no music. Schuman's view, of course, was that while skills and techniques are necessary, those skills should never be divorced from music itself. Music, in his view, should be taught from music, not from textbooks.

Accordingly, he replaced the school's theory department with a new, all-embracing program, christened Literature and Materials of Music, which embodied the en tire theoretical curriculum and paralleled the students' major study. L&M, as it soon came to be called for convenience, represents an approach, a philosophy, rather than a method, for the point of the program lies in its very luck of method or regimentation, in its dependence upon a built-in flexibility. Each instructor is given a relatively free hand to introduce and refine his students' theoretical skills and knowledge, to teach as he thinks best. The emphasis in all study is laid upon music itself; students are expected to derive theoretical principles and compositional practices through studying scores, preparing works for performance in class, and writing music.

During the Juilliard years Schuman continued to grow in stature as a composer. Rigidly apportioning his time so that neither the school nor his composition would suffer (he actually calculated his necessary composition hours at four- to six-hundred a year, and he kept careful track of each day's minute-count), he turned out a number of major works during this period. In 1947 he wrote his first score for Martha Graham, Night Journey, followed two years later by Judith, one of his most famous works and one of her classic solos. Like Undertow, his earlier dance score, Judith is a work full of tension and suspense. But Judith is a tale of hope, of righteousness, of vengeance and vindication, and these positive aspects of the story are reflected in the intense drama of the music. Between these two scores for Martha Graham came the Symphony No. 6, in 1948, commissioned by the Dallas Symphony and introduced by conductor Antal Dorati. In one movement, opening and closing with parallel reflective sections, it is an immensely satisfying work for the listener. The String Quartet No. 4, commissioned by the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation in the Library of Congress, was written in 1950. Technically intricate ("It is," comments Robert Mann of the Juilliard Quartet, "one of the most difficult contemporary quartets in the repertoire") and musically concise, it makes great demands on both performers and listeners. The years 1951 1953 saw the composition of Schuman's sole opera, The Mighty Casey, with a libretto by Jeremy Gury based on the famous poem Casey at the Bat. Although the work has enjoyed several performances, including one produced for television, it has never achieved the success of many of Schuman's other works.

Schuman's cycle of five piano pieces, Voyage, was written in 1953. In it he demonstrates that, although not a pianist himself, he can exploit the sonorous possibilities of the instrument effectively in a generic virtuoso work.

The following year he wrote one of his most eloquent orchestral scores, Credendum, subtitled "Article of Faith," commissioned by the U.S. National Commission for UNESCO through the Department of State. According to informed reports, this was the first time a musical work had been commissioned in this country through diplomatic channels. Strong and affirmative, it flows easily in its reflective sections and enjoys both brilliance and rhythmic excitement in its more dramatic moments. It is a successful score on all counts, and the UNESCO people surely got their money's worth.

It was in 1956 that Schuman wrote what may well be his best-known and most widely popular piece, the New England Triptych ("Three Pieces for Orchestra after William Billings"), commissioned by Andre Kostelanetz.

Although the original tunes are Billings', the treatment is completely Schuman's. Each of the Billings songs serves as the basis for an orchestral fantasia-variation. The first, Be Glad Then, America, incisive, bold, and brassy, subtly retains Billings' primitivism within the twentieth-century treatment. Combining elements of an old-time camp meeting with exciting jazz rhythms, it is, within the orchestral context, band music at its best. The middle movement, When Jesus Wept, is handled pensively and with appropriate simplicity. The finale, Chester, is again bold and brassy, full of energy and spirit.

A month after he had completed the New England Triptych, Schuman wrote a new and expanded version of the final movement to satisfy a commission he had received for a band work. In its version as an Overture for Band, Chester is no mere transcription of the orchestral original. Rather, it is in many ways a completely new piece. Longer than the original by almost half, the band version extends the treatment of the orchestral variations and interpolates several new variations. Even the scoring is altered in many significant details, as is the modulatory scheme. Working with the detachment that he might bring to another man's composition, Schuman built an entirely new piece on the basic structure of the original. Chester has become a favorite with audiences, who like its verve and sophistication.

For his own amusement, and perhaps for some compositional relaxation, Schuman rounded out the year 1956 with a set of Four Rounds on Famous Words for a cappella chorus. Witty and imaginative, they are captivating little pieces. Two years later, on a commission from St. Lawrence University, he wrote what may well be his most profound choral work, three Carols of Death, to poems by Walt Whitman. Extremely moving, infused with a deep sense of tragedy, they are among his finest works.

-------- Joseph Fuchs, Schuman, Norman DelloJ oio, and conductor

Jean Morel after a rehearsal of Schuman's Violin Concerto in 1960.

In 1959, Schuman completed the final version of his Violin Concerto, a work which had concerned him since 1947. Originally commissioned by Samuel Dushkin, it was first presented in 1950 by Isaac Stern with the Boston Symphony under Charles Munch. A revised version was introduced, again by Stern, in 1956, but Schuman was still dissatisfied with it. In its final version, performed at Aspen by Roman Totenberg (Izler Solomon conducting) during the summer of 1959 and repeated the following winter in New York by Joseph Fuchs, the Concerto is an expansive two-movement work with several subsections in varying tempos within each movement. A companion piece, composed in 1961, is the Fantasy for Cello and Orchestra, A Song of Orpheus. Written on a Ford Foundation commission for Leonard Rose, the work is based on Schuman's earlier song of the same title. Again the solo string instrument is treated sympathetically, and again its virtuoso and lyric possibilities are given full play.

Like the Violin Concerto, it is a richly romantic work.

Between the two solo works came the Symphony No. 7, of 1960, written to celebrate the seventy-fifth anniversary of the Boston Symphony. A single-movement work, it reflects the growing romanticism of the two solo works while retaining Schuman's old orchestral glamour and rhythmic verve. It also reveals an increasing complexity and subtlety of style, noticeable since the Symphony No. 6 and Credendum, which seem to grow out of a new questing for a deeper and perhaps different mode of expression-for, by the middle Sixties, Schuman was no longer an innocently brash young man, nor was the world any longer as brightly uncomplicated as it might have seemed when he was growing up in the Twenties.

IN September of 1961, Lincoln Center announced the appointment of William Schuman as its new president.

The reaction on all sides was: "It's a natural." The choice of Schuman seemed inevitable. As president of Juilliard he had proved his executive abilities: running a school such as Juilliard requires the talents of an administrator and a businessman, and Schuman had demonstrated he possessed them. Further, as a composer and an educator, he was a leader in the artistic community. Who better to head up Lincoln Center, the country's first major arts complex? Just as Schirmer's had earlier been applauded for appointing a working composer as its editorial head, so was Lincoln Center (at that time necessarily preoccupied with its massive construction and fund-raising operations) applauded for appointing a working composer, an articulate artist, as its head.

Schuman arrived at Lincoln Center at the beginning of 1962, and it was not long before the Lincoln Center offices took on that same atmosphere of electric excitement which had surrounded him at Juilliard. When he arrived, Philharmonic Hall (now Avery Fisher Hall), the first building of the complex to be completed, was just beginning to be recognizable. Although all the other halls were yet to be built, Schuman, a man who conceives sweeping innovations as casually as another man considers the weather, immediately embarked on long-range plans for the Center's artistic activities.

One of his first concerns, as might be expected, was the Center's educational activities. As president of Juilliard, he had already negotiated the terms on which Juilliard would join the Center as its school-in-residence. But from the beginning, Lincoln Center had envisioned some kind of broad educational program. Schuman's first move was to invite his friend and colleague from Juilliard, and formerly dean there, Mark Schubart, to head the Center's educational activities, which are today among the most vital aspects of Lincoln Center.

It was during the years of Schuman's presidency that the Repertory Theater of Lincoln Center, created by the Center as a new constituent, moved into its permanent home at the Vivian Beaumont Theater, and the New York City Center moved its ballet and opera companies into the New York State Theater. Schuman's presidency saw the opening of Philharmonic Hall-the official opening of the entire Center-and the opening of the new Metropolitan Opera House; it also saw the establishment of a new branch of the New York Public Library at the Center, the Library and Museum of the Performing Arts. It was Schuman who gave support to the establishment of the Chamber Music Society, and Schuman who conceived and fought for the creation of the Film Society.

His biggest ideas, however, were in the area of programming. Under Schuman, the Center instituted its "Great Performers" series and undertook the sponsor ship of regular international choral festivals. The Center also presented two summer festivals, in 1967 and 1968; both were artistic and popular successes. Attendance was particularly gratifying, for it proved the existence of a summer audience. But the festivals were expensive, and Lincoln Center, despite its image of affluence, was still faced with the problem of raising money to cover the steadily increasing costs of construction, as well as funds to finance future operations. Everybody agreed with Schuman that Lincoln Center should take the initiative in providing artistic leadership. Everybody agreed that the Center could not, and should not, confine itself merely to the chores of real-estate management. But artistic leadership costs money. It was beginning to look as if Schuman was the right man for the job-but at the wrong time.

In the summer of 1968, Schuman suffered a mild heart attack. During his four months' enforced rest he had plenty of time to think, to review his present activities, and to contemplate the future. The job at Lincoln Center had proved to be enormously time-consuming; plans and projects were fine and challenging, but the daily details and problems were drawing him farther and farther away from music. With all his energy and self-discipline, he found his time for composition steadily diminishing. The possibilities at Lincoln Center were great, but until the Center's financial problems could be solved (and this promised to be a long-term business), those possibilities faced constant frustration.

When he returned to Lincoln Center in the fall, he had made up his mind. It had been a glorious seven years; he had accomplished a great deal at and for Lincoln Center; he had made many good friends. The job was a challenging one, but the time had come for him to give up executive responsibilities and return to music. His resignation was announced in December of 1968. The Board immediately named him President Emeritus (thus putting that title into the plural for him, since he is also President Emeritus of Juilliard), citing him for having led Lincoln Center "through seven years of growth, experiment, innovation and achievement." Schuman's first major work during his Lincoln Center years was the Symphony No. 8 of 1962, commissioned several years earlier by the New York Philharmonic in anticipation of the opening of its first regular season in Philharmonic Hall. A tight and sure work, it reflects his increasing subtlety of expression while retaining his characteristic drive and thrust. Its effective exploitation of the orchestra's resources musically affirms his frequently stated faith in the future of the symphony orchestra.

----

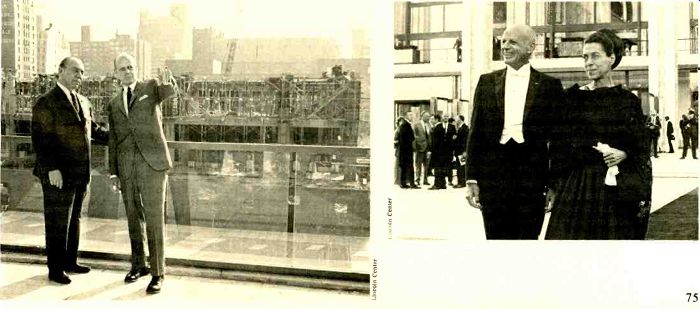

Schuman with Richard Rodgers during the construction of Lincoln Center; Rodgers became President of the N.Y. Music Theater.

Mr. and Mrs. Schuman at the first, gala opening night of the Metropolitan Opera House at Lincoln Center, September 16, 1966.

===============

ON LISTENING TO WILLIAM SCHUMAN'S MUSIC

THE American Festival Overture, although written when Schuman was only twenty-eight years old, is as good an example as any of many of the elements of his musical style, and provides a useful launching point for a discussion of "what makes Schuman sound like Schuman." What impresses the listener first is its brilliant and compelling orchestration.

Each instrument, and each choir of instruments, is handled with sure under standing. Schuman's admitted lack of expertise on the piano has proved a compositional blessing. "I'm not a pianist," he says, "and this makes it hard for me to write for the piano. But it helps my other music." Since he does not com pose at the piano, Schuman works directly with his orchestral score, singing the individual lines as he works, notating and thinking each passage in terms of the instrument it is designed for. The result, evidenced as early as this overture, is that he writes music that sounds.

Rhythmically--for rhythm is one of the most important elements in Schuman's stylistic profile-the American Festival Overture is also typical. We find here the rhythmic drive and the irresistible propulsion that mark so much of his work. We also find the rhythmic ingenuity typical of his style, for, despite the force of his rhythmic drive, he is unwilling to confine himself to a steady, inexorable beat, or to regular, repetitive rhythmic patterns either. His favorite rhythmic device, borrowed possibly from his jazz days, is the off-beat accent. Whenever possible-and whenever effective- he tends to avoid accenting the strong beats of the bar, and particularly the first beat. Melodies start just after that first beat; accents occur on the second half of a strong beat; rhythmic patterns cross bar-lines with impunity, creating not only off-beat pulses, but energetic, implied cross-rhythms.

Schuman's rhythms are typically syncopated-but he carries syncopation to its most sophisticated extremes. He is fond of groupings of four notes: some times they are treated as continuous running passages; more often their implied accents are displaced, and they take on a breathlessness and nervous energy through the dropping of the fourth note of each group. As a matter of fact, in the composer's rhythmic style the release of a note is as important as its attack--sometimes even more important. And he carefully notates his rests. If a note is held beyond the time indicated (and in fast passages this be comes crucial), the implied syncopations, the implied cross-rhythms between at tacks and releases, are destroyed, and much of the rhythmic impact is lost. He is also fond of triplets, or groupings of three notes in the rhythmic space of two beats, using fast triplets to propel and slow ones to create tension.

The American Festival Overture bears out Schuman's own contention that his music is both melodic and singable.

Granted, his tunes cannot necessarily be whistled after a single hearing, but he insists that anyone who can sing The Star-Spangled Banner can learn to sing his melodies. It takes only a little practice, for the music is essentially ton al, and that immediately gives the listener something to hang on to. He likes large skips, very often of a seventh, and his melodies usually leap vigorously upward, a reflection of his own essentially affirmative approach to things. The chromatic alterations occurring within melodic lines are not problematic; while they lift the line out of the bounds of a single, strict tonality, they are always logical and seldom upsetting. It should be remembered that Schuman's melodies, like those in all music, depend upon their rhythmic structure for their individual personality. The notes alone, without the rhythm, mean very little.

SCHUMAN is generous with his instrumentation, calling for a full complement of winds and brass, and usually for a rather large percussion section. The bass clarinet, still viewed in many quarters as a slightly exotic "extra" instrument, appears in almost every one of his scores, often as a solo instrument. So does the English horn. He has a fondness for pulling out two or three solo winds for brief chamber-music-like excursions. His writing for percussion is always imaginative, and one of his favorite and most effective devices is the timpani solo: rising from subliminal rhythmic depths, the timpani emerge as melodic instruments.

He also likes to treat his instruments in blocks, pitting the winds against the strings, the brass against both, the percussion against everything. His music is full of brilliant antiphonal passages: wit ness the opening of the American Festival Overture, in which the materials shift from one instrumental choir to another, often overlapping in their eagerness to be heard. From full-orchestra passages, instrumental blocks will emerge. The contrasts between these blocks of sound, and the impact when they combine, are basic to his orchestral style.

Schuman himself credits Roy Harris with introducing him to sixteenth-century music, and this proved to be a significant acquaintance, for like his sixteenth-century predecessors, he is primarily a linear composer. Basing his works on moving melodic lines rather than on firmly planted vertical harmonies, he creates harmonic sounds that are the result (carefully planned and controlled) of his chromatic moving melodies.

On occasion, of course, he will write a purely harmonic passage, generally in block chords. When necessary, he can write a strictly "correct" chorale pas sage. Usually, however, he alters the chords just enough to produce an individual, and thoroughly twentieth-century, sound. Most often basically triadic (chords built in thirds), the harmony takes on color and individuality through the dissonant tones added to the basic chords. He likes to treat chords in blocks, too, and these blocks are often poly-chordal or polytonal, with treble and bass implying allegiance to different, and unrelated, keys. By spacing out his dissonances, and by separating his chord members and the non-chord tones, he can produce a texture in which the dissonances rub against each other, pulling and straining but rarely clashing. With the years, this kind of harmonic usage has grown increasingly sophisticated and subtle. Compositional intricacies he usually reserves for his contrapuntal passages; the harmonic sections often reveal tonal tension and rhythmic repose.

Schuman likes ostinato (regularly repeated) rhythms and the contrast possible between long, flowing melodies and rapidly moving accompaniment lines in detached notes. Often, as in the peroration of the American Festival Overture, what looks on the page like a virtuoso passage for strings or winds turns out to be nothing more than a continuous sweep of sound accompanying the sonorous melodic line emerging in the brass.

This rapid passage of many notes creates the kind of sound background that is typical of the composer's style.

WHAT welds these compositional de tails into a cohesive and communicative piece of music is an unusually fine sense of organization. While not all of his works follow traditional forms (the American Festival Overture is in a clear three-part A-B-A), they all exhibit a sure discipline in the handling of contrast and repetition, exposition and development of ideas, emotional tension and release.

Schuman never fools his listener. He sets up expectations of climax which are rewarded at the right psychological moment. He relieves suspense before it has had a chance to exhaust itself; he tempers drive with repose. There is clarity of both form and texture in his music: he is a clean composer.

=============

----------

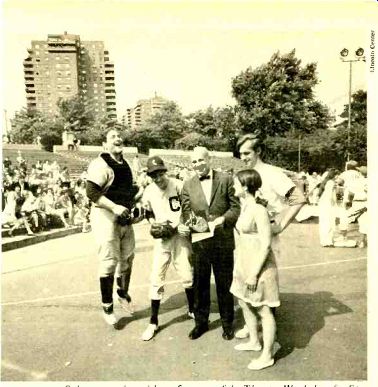

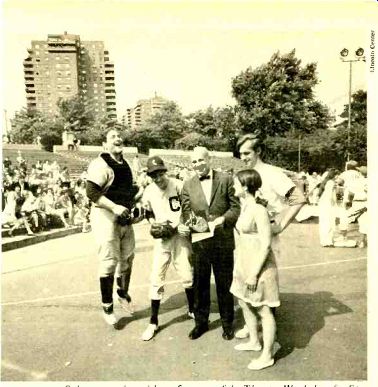

Schuman quips with performers of the Theater Workshop for Students preparing a performance of his baseball opera, The Mighty Casey, given at New York's East River Amphitheater in 1967.

The following year, for Broadcast Music's twentieth anniversary, he balanced the essential seriousness of his symphonies with an orchestral version of Charles Ives' Variations on America. Schuman must have had real fun with it; Ives' renegade humor obviously appealed to him.

Ives had scored his Variations for organ; Schuman retained the original parts (only shifting them occasionally to a new register) but added his own percussion. The piece, whose brilliance and humor are irresistible, has proved enormously popular. In the same year, for his own pleasure, Schuman made an orchestral version of The Orchestra Song, a traditional Austrian folk piece which he had earlier set (with an imaginative translation of the text by Marion Farquhar) for chorus. In 1964 he wrote one of his rare chamber works, Amaryllis Variations for String Trio, commissioned by the Elizabeth Sprague Coolidge Foundation in the Library of Congress.

Using the early English song as his theme, he treats the sweetly modal melody to a series of contrapuntal and rhythmic variations in which the sounds of the twentieth century combined imaginatively with the spirit of the sixteenth.

In 1968, his last year at Lincoln Center, Schuman wrote two major works, both intensely serious. To Thee Old Cause, written for the New York Philharmonic's 125th anniversary, is subtitled "Evocation for Oboe, Brass, Timpani, Piano, and Strings." The title derives from a passage in Walt Whitman's Leaves of Grass. Introspective, with tension growing from understatement, the work reflects Schuman's growing concern for the human condition. The Ninth Symphony, subtitled "Le Fosse Ardeatine," is similar in mood and style. Schuman's only programmatic work, it is a passionate and deeply humanitarian statement of his reaction to a visit to Rome's Ardeatine Caves. There, in 1944, the Germans murdered over three hundred Italians in reprisal for the killing of thirty-two German soldiers by the Italian underground. It is an intense and essentially tragic work, expressing both compassion and protest.

Schuman's first work after leaving Lincoln Center was a musical tribute to the painter Ben Shahn, entitled In Praise of Shahn. Outgoing, despite its considerable contrapuntal complexity, it combines a slightly exotic. almost near-Eastern principal melody (a subtle comment on Shahn's Eastern European-Jewish background) with a bold orchestral development.

The year 1971 saw the composition of a set of four Mail Order Madrigals for a cappella chorus to texts from the 1897 Sears, Roebuck Catalog, and the Declaration Chorale, also for a cappella chorus, commissioned by the 1972 Lincoln Center Choral Festival. Voyage for Orchestra, commissioned by the Eastman School of Music on the occasion of its fiftieth anniversary, was introduced in 1972, and in 1973 Schuman completed his Concerto on Old English Rounds, for Viola, Women's Chorus, and Orchestra, commissioned by the Ford Foundation for violist Donald McInnis.

TODAY, at sixty-three, William Schuman still presents that aspect of vitality and exuberance which characterized him as a young man. If he had a taste for that kind of thing, he could indulge himself in reviewing past accomplishments and honors, for he has a long list of them. But he spends little time on the past, for he is too busy looking ahead. He remains a man with a future. He is still an early riser, and finds that his best working hours are in the morning. There was a time when each day was rigidly apportioned into the hours scheduled for composition and those for Juilliard or Lincoln Center responsibilities.

Now he enjoys the luxury of sleeping as late as 7:30 or 8:00 ("But I'm completely awake as soon as I get up") plus the freedom of working at home on a considerably less regimented schedule. He has not dropped his outside activities, however, and devotes a great deal of time to the numerous boards on which he serves. His public services include, to name only two, the chairmanship of the executive committee of the Chamber Music Society of Lincoln Center, and the chairmanship of the MacDowell Colony.

In his student days he was an enthusiastic concert-goer ("I went to everything") and record listener. Now he uses recordings primarily to learn repertoire. When he attends a concert purely for pleasure (he still shows up at a certain number of "duty" concerts), it's apt to be an orchestral performance. "I'm wild about the orchestra, and of ten sneak in to rehearsals to hear specific works." As for the composers he favors: "I'm hard-pressed to think of any composer I don't admire. If I had to name favorites, I would pick out Lassus and Bach, and would underline Beethoven. I'd minimize Wagner and Liszt, but would include Berlioz, Ravel, and Debussy for orchestration. I'm a great Tchaikovsky fan. And I'm still crazy about the Americans of my youth, Harris and Copland particularly." Of today's younger composers: "I'm all for them in theory. It's necessary for them to be superior and dismissive of their elders; if they weren't, I'd worry. But I find no compulsion to agree with them or to listen to their music. I'm still a liberal, though, and feel they should go ahead." His own musical creed is a very simple one: "I am a Romantic."

Sheila Keats graduated from Juilliard during the Schuman years.

A pianist and accompanist for string players and associate director of the School for Strings, she writes often on music.

+++++++++++++++++

----------

Also see:

TECHNICAL TALK--What Is Noise?

Tales from the Studio--CRESCENDO! Even discord can be, in its own way, sweet. by JACK SOMER