------- Falstaff and His Friends: engraving after a painting by C. R. Leslie,

R. A.

Another Falstaff: Vaughan Williams' Irresistibly Beautiful Sir John in Love

THERE seems to be nothing exceptionable in the view, shared by a number of outstanding musical minds, that the rotund figure of Sir John Falstaff, one of the great comic creations of western literature, was destined for a long life on the opera stage. But what do the facts tell us? Ambroise Thomas' Le Songe d'une Nuit d'Ete (1850), which is not, properly, Shakespeare's A Midsummer Night's Dream but a composite that includes the character of Falstaff, is a forgotten French curio. Gustav Hoist's At the Boar's Head (1925) is an equally neglected English one. Otto Nicolai's The Merry Wives of Windsor (1849), a genuine comic masterpiece, is appreciated only in German-speaking lands, and, while Verdi's Falstaff (1893) is a connoisseur's delight, audiences simply do not respond to its magic with the enthusiasm they lavish on many a lesser Verdi work. To complete the negative evidence, Ralph Vaughan Williams' Sir John in Love (1928), which is more faithful to the Shakespearean original (The Merry Wives of Windsor) than either the Nicolai or the Verdi opera-and in English to boot-has been treated to no more than a cool reverence in England and never exposed anywhere else.

Now that I have heard Angel's just-released first recording of Sir John in for this is positively not only a skillful and effective opera, but an irresistibly beautiful one as well, colorful, varied, full of sing-able tunes and richly orchestrated passages that recall the most inspired pages of the symphonic Vaughan Williams. Little is served by comparing Sir John in Love with Verdi's Falstaff, yet such a comparison is inevitable.

Alongside Verdi's brilliant, mercurial score, Vaughan Williams' appears the more lyrical, the more leisurely, perhaps even somewhat rambling in its unfolding.

The opera's focus, moreover, is not al ways on the good knight himself-the cast is more numerous than Verdi's, and there are episodes in which Falstaff does not even appear. When he does, he is less boisterous (more English?) than the Boito/Verdi character; even his drinking is more restrained. He is, in short, a more poetic figure, and his final humiliation is fittingly meted out with relative leniency. For all the beauty of the scoring, however, Vaughan Williams does not conjure up the instant magic of, say, Verdi's inspired "Reverenza" (when Mistress Quickly comes to call) or those unforgettable two measures on the words "dalle due alle tre" (in Act II, the hours when Falstaff is directed to come wooing Mrs. Ford).

It is surely not surprising at this late date to discover that Vaughan Williams was not quite the equal of Verdi in composing operas. Yet Sir John in Love is an outstanding opera, a work in which an Elizabethan text (the composer's own, though based on Shakespeare) is artfully matched to Elizabethan tunes. Some of these (including the familiar Greensleeves) are authentic pieces of folk derivation, and they are all identified as to source in the excellent accompanying notes by Michael Kennedy. But when the composer works with his own melodic inspirations, the results are so authentic, so grounded in the idiom, that one cannot tell the difference.

Some of England's most prominent vocal artists are in the Angel cast, and they form such an excellent ensemble that it is difficult to single out individual interpreters for honors. Doing so reluctantly, however, I would award pride of place to Raimund Herincx for a mellow, philosophical Falstaff that seems to ac cord perfectly with the composer's view of the knight, and a laurel to Wendy Eathorne for an exquisitely sung Anne Page. And all the others, excepting only the interpreters of the roles of Fenton and the parson Evans, are very nearly ideal from both the vocal and dramatic viewpoints. Finally, none but the highest praise will do for conductor Meredith Davies' direction of the fine orchestral performance and for John Alldis' handling of the sonorous and flavorful choral contributions.

A major artistic oversight has now on records at least-been rectified, so let us look forward to performances of Sir John in Love in opera houses on both sides of the water. They need not be expensive to mount-there are all those costumes, all that scenery standing by from existing productions of Falstaff.

George Jellinek

VAUGHAN WILLIAMS: Sir John in Love.

Raimund Herincx (baritone), Sir John Falstaff; Robert Lloyd (bass), Ford; Elizabeth Bainbridge (mezzo-soprano), Mrs. Ford; John Noble (baritone), Page; Felicity Palmer (soprano), Mrs. Page; Wendy Eathorne (soprano), Anne Page; Robert Tear (tenor), Fenton; Rowland Jones (baritone), Sir Hugh Evans; Gerald English (tenor), Dr. Caius; Helen Watts (mezzo-soprano), Mrs. Quickly; others. John Alldis Choir; New Philharmonia Orchestra, Meredith Davies cond.

ANGEL SCLX-3822 three discs $21.94.

Papa Haydn's Wind-Band Mass: Glorious Almost Beyond Description

THE three-week Haydn Festival at the Kennedy Center in Washington, scheduled to begin September 22 and to incorporate an international musicological conference, is said to be the first festival of any kind in this country to be devoted entirely to Haydn. That is not so surprising if we remind ourselves that the "rediscovery" of Haydn as one of music's most towering figures (instead of a merely "charming" secondary one) began in earnest, as far as the general public is concerned, only about twenty five years ago. By now all the dozens of symphonies, string quartets, and key board sonatas are well accounted for on records (and in authentic editions as well), and, aside from the operas (which Antal Dorati will begin recording soon for Philips), the one category of major works in Haydn's vast catalog which remains only slightly known is his Masses. Haydn himself, whose judgment rarely failed him, confessed to being "rather proud" of them, and indeed they contain some of the finest music he composed in any form. The last of them, the so-called "Harmoniemesse," which happens also to be the last major work he completed, is glorious almost beyond description, with, among other features, the largest orchestral complement in the series and an unusual prominence for the various wind instruments in all its movements.

Leonard Bernstein's new recording of the work is hardly less glorious than the music itself: the performance is so consummate a realization of Haydn's grand conception that the two elements need scarcely be considered in separate terms.

This "Wind-Band Mass" ("Harmonie messe"- Harmonie being the term used in much of Central Europe for "wind band"), written as Haydn entered his seventy-first year, is no autumnal, valedictory gesture, but an exultant, jubilant work by a composer who may have known weariness but only grew more imaginative and more confident in his powers as he grew older. Haydn is said to have remarked more than once that "God, having given me a cheerful heart, will forgive me if I serve him cheerfully," and this entire final Mass is a veritable Ode to Joy with a liturgical text substituted for Schiller's. Through out the work the various winds, solo or in delicious combinations, paint intriguing nature pictures; festive fanfares and drums punctuate the sequence, and there is little of solemnity except in the Kyrie, the very moving Crucifixus, and the opening of the Sanctus. The orchestral and choral coloring has a mellowness similar to that of The Seasons, which was completed only the previous year, while the rhythms convey the almost bursting vitality of Haydn's most exuberant middle-period symphonies.

One of the most astonishing departures from the expected is the setting of the Benedictus not as a serene and gentle aria but as a downright jaunty little march. Another is the concluding "Dona nobis pacem." In some Masses the imploration is almost tearful; in Haydn's own Mass in Time of War it is a thunderous demand for peace instead of a meek petition. Here the exhortation is almost giddy-"feuertrunken," one might say--until there comes an abrupt hush and the soaring final amen. These touches of jollity in no way diminish the grandeur of his work-as exemplified in the fugal conclusions of the Gloria and Credo but are simply part of the human balance that was so characteristic of Haydn, and in his greatest works most of all.

There can be few scores of any kind whose vigor, joy, and unlabored exaltation find so close a parallel in the characteristics of Bernstein's music-making.

--------

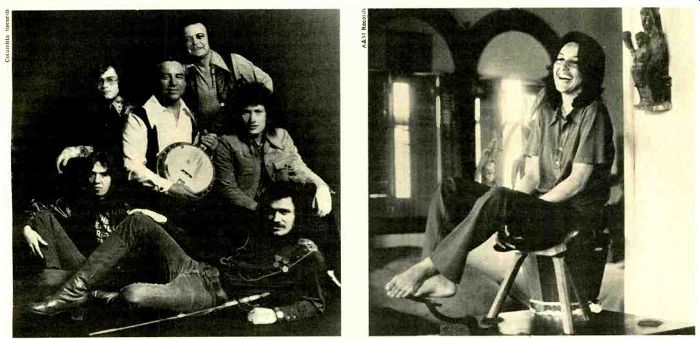

THE SCRUGGS REVUE: left to right, Jody Maphis, JOAN BAEZ The instincts of a born storyteller

His response to this magnificent stimulus, as I have already suggested, is in the nature of a fulfillment rather than a mere "interpretation," and not one of his associates lets him down. Special mention might be made of Frederica von Stade's lovely singing of "Gratias agimus tibi" in the Gloria and of Judith Blegen's in "Et incarnatusest," but all four soloists are unfalteringly excellent, the Philharmonic is the great orchestra it becomes only in Bernstein's hands, and the choral work too is first-rate (though I could have taken it lustier still). The sound, a little boxy at isolated points in the two-channel version I heard, is for the most part richly realistic. One hesitates to overwork such words as "inspiration" and "glory," but these are the qualities that shine from every bar of this beautiful performance.

Richard Freed HAYDN: Mass No. 12, in B-fiat Major ("Harmoniemesse"). Judith Blegen (soprano); Frederica von Stade (mezzo-soprano); Kenneth Riegel (tenor); Simon Estes (bass-baritone); Westminster Choir; New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein cond.

COLUMBIA M 33267 $6.98, MQ 33267 $7.98.

"Aura" Had Nothing To Do with The Triumph of Joan Baez

MIDWAY into the succeeding dec ade is a fairly good vantage point from which to judge what was really worthwhile about the preceding one.

Looking back, it seems to me that sorting out the real accomplishments (and accomplishers) of the chaotic Sixties may take us a little longer than usual, but at least one thing has become perfectly clear: in the skittish, fad-obsessed world of pop music, Joan Baez is, and has been, a superb performer. For a long time, the political activism, the almost belligerent "lifestyle," and the rather pompous, even comic Cassandra/Joan of Arc aura that were all too often the principal ingredients of her public image clouded judgments--both pro and con--about her. But she has endured, and aura had nothing with it. Her triumph is entirely owing to her remarkable voice and her incredible lyric skill, both of which leap powerfully out of her new A&M release "Diamonds & Rust." To describe Baez's voice to anyone who hasn't heard it (is there anyone?) is extremely difficult. It is, yes, pure, and it is clear-but it is also thready and vibrant and, well, mysterious. It can, when it chooses, rake the skin swiftly and draw blood. Or it can flicker lightly, lovingly, and unexpectedly across the ear like a breeze. And it can simply float off freely on its own, vanishing on the air.

Baez's way with a lyric is that of a born storyteller, with all the gifts of humorous mimicry, dramatic instinct, and acting skill that implies. But it is the way the two go so effortlessly together-the rippling, changing voice and the easy, confident play with words-that makes her work so consistently fascinating, so entirely her own.

"Diamonds & Rust" is, as the title suggests, a pleasant, rambling mix of elements. Simple Twist of Fate, for example, is a surprising and delightful rock number which she floats through with the self-possessed aplomb of a duchess at a servants' ball. Her performance of Stevie Wonder's Never Dreamed You'd Leave in Summer is as haunting and beautiful as Children and All That Jazz, in which she accompanies herself in a weird falsetto, is eerily appealing.

If she had asked me, I'd have advised against including the title song here, which she wrote and which seems to be about her long-ago and best-forgotten affair with Bob Dylan. Oh, it's per formed well enough, but I'd put the interest level of its subject matter about on a par with a Fay Wray essay on the architectural beauties of the Empire State Building. That lapse aside, the rest demonstrates, and well, that Joan Baez has her place in the very front rank of American popular singers. Peter Reilly

JOAN BAEZ: Diamonds & Rust. Joan Baez (vocals and guitar); orchestra. Diamonds & Rust; Fountain of Sorrow; Never Dreamed You'd Leave in Summer; Children and All That Jazz; Simple Twist of Fate; Blue Sky; Hello in There; Winds of the Old Days; Jesse; Dida; I Dream of Jeannie ; Danny Boy. A&M SP-4527 $6.98, OO 4527 $7.98, cass. 4527 $7.98.

---------------

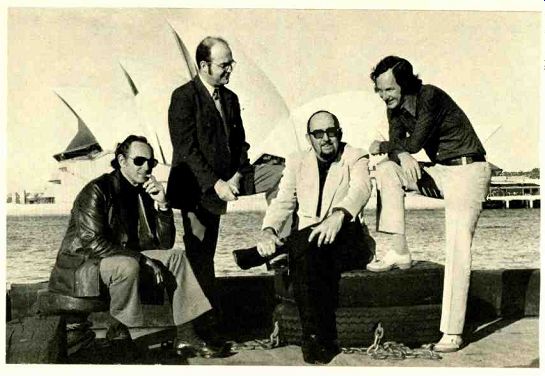

DON BURROWS QUARTET: that's the Sydney Opera House in full sail behind Don Burrows, George Gollu, Ed Gaston, and Laurie Thompson

-------

Earl Scruggs Revue: Hard to Go Wrong With Their Anniversary Special

EARL SCRUGGS and his boys went out and got a little help from all sorts of friendly hippies and hillbillies- well, actually, only the better sorts of each-- and the result is a fine first volume of their Anniversary collection (which has little to do, of course, with what the Earl Scruggs Revue usually sounds like). If I read the credits and listen to the rhythm section correctly, the Revue's drummer, Jody Maphis, hits nary a lick on this one.

But the Revue alone does sound pretty good-or can at times: at least two members, papa Earl and son Randy, whose flat-picking style may be the most ferocious-looking attack on a guitar you've ever seen, are inordinately talent ed. And until recently, the Revue contained a second Living Legend, the great dobro player Josh Graves. He's leading his own band now and doesn't appear here, but they could have used him since the sound isn't quite as crowded as the guest credits suggest.

I really like the sequential-vocals thing they do on several of the songs-for one album's duration, at least, I like it-with Joan Baez singing the first verse, Tracy Nelson the second, Loudon Wainwright III the third, and so forth. There's a bit of competitiveness in all this, of course, and I can't help noticing how often Joan Baez outclasses the whole pack, even before you come to her shrewd parody of Dylan's phrasing that follows a stint by (grab your hat, or something) Leonard Cohen. But then the collaboration of Scruggs and Johnny Cash (two of the more decent American institutions) in Cash's Hey Porter is the kind of keep sake performance that makes the whole album worth buying too, and if you like folkie-country stuff at all, it's difficult to go wrong with this. Noel Coppage

THE EARL SCRUGGS REVUE: Anniversary Special Vol. 1. Earl Scruggs (banjo, vocals); Randy Scruggs (guitar, banjo); Gary Scruggs (vocals, bass); Joan Baez, Johnny Cash, Tracy Nelson, Ramblin' Jack Elliott, the Pointer Sisters (vocals); Roger McGuinn (electric twelve-string guitar); Billy Joel (piano); other musicians. Banjo Man; The Swimming Song; Gospel Ship; Bleeker [sic] Street Rag; Royal Majesty; Rollin' in My Dreams; Song to Woody; Third Rate Romance; Hey Porter; Passing Through.

COLUMBIA PC 33416 $6.98, PCA 33416 $7.98, PCT 33416 $7.98.

The Don Burrows Quartet Testifies to the Health of Jazz Down Under

THE Don Burrows Quartet appeared in concert at the Sydney, Australia, Opera House in March of last year, and the resulting live recording, according to the jacket, was voted Australian Jazz Album of the Year. We are not told who the voters were, nor do we know what the group's competition sounded like, but the music of the Don Burrows Quartet easily measures up to some of the best stateside offerings of 1974.

This is, of course, not our first taste of jazz from Down Under. The Graham Bell Dixieland Band was among the better New Orleans revivalist bands in the post-war years, and the latter half of the Fifties saw the Australian Jazz Quintet gain considerable popularity here, its sound-characterized by prominent use of the bassoon-being pleasantly different from what we were then used to hearing. However, the rigid framework within which the AJQ performed often made it as predictable as a pre-classical quartet. The Burrows group is far less rigid and eminently more interesting. Its music, too, is of the chamber-jazz variety, exhibiting the discipline, musician ship, and good taste of the late Modern Jazz Quartet, but, owing to Burrows' use of disparate instruments, producing a wider variety of sounds.

Burrows is master of his instruments, whether it is the electric clarinet lending unusual character to the light Latin beat of Maybe Today or the flute a la Jeremy Steig giving Sweet Emma some rhythmic lashes. Guitarist George Golla is also superb throughout, and particularly so on Luis Bonfa's The Gentle Rain, where he solos extensively. There is a notable rapport between Burrows and Golla, but bassist Ed Gaston and drummer Laurie Thompson aren't exactly alien to what is happening, and their sensitive playing therefore goes far beyond mere support.

Each selection in this well-chosen pro gram has its own identity and there is not a dull measure in the lot. If this album is any indication of what is happening there jazz-wise, the Motown/Philly Sound pollution, which is choking so many of our own jazz masters, would appear not to have reached the dangerous level as yet in Australia.

Chris Albertson

DON BURROWS QUARTET: The Don Burrows Quartet at the Sydney Opera House. Don Burrows (clarinet, electric clarinet, flute, alto flute, soprano and baritone saxophones, percussion); George Golla (guitar); Ed Gaston (acoustic and electric basses); Laurie Thompson (drums). Sweet Emma; Maybe Today; Velhos Tempos; Yesterdays; The Gentle Rain. MAINSTREAM 416 $6.98.