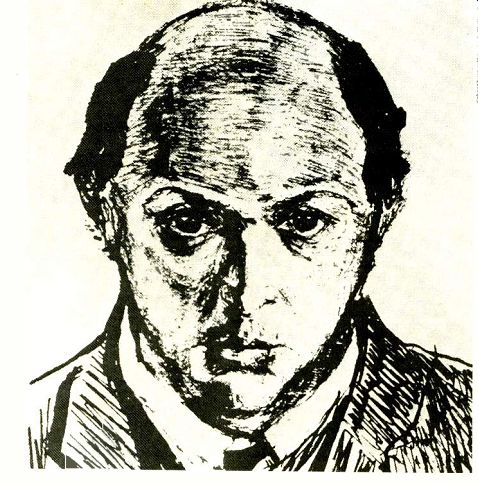

"Treating Schoenberg like Beethoven or any other master.."

THAT the composers of the modern Viennese school- Arnold Schoenberg and his pupils Alban Berg and Anton Weber belong in the direct line of the great Classical-Romantic tradition is evident to anyone familiar with their work. The transition from late Romanticism to Expressionism was, in fact, nothing like the revolutionary upheaval it has long been made out to be, but a surprisingly short evolutionary step. This evolution is clearest and most highly developed in the work of Schoenberg, whose music and personality were controversial for so long that audiences and critics refused to hear the obvious. Now that we have so thoroughly re-evaluated late-nineteenth-century and turn-of-the-century art, however, there is an in creasing acceptance of the Viennese school's transitional art by the wider musical public, an acceptance underlined by several recent record releases.

Schoenberg's first published work, Ver Wide Nacht, still his most popular composition, belongs to the nineteenth century (it was composed in 1899), but with the massive Gurre-Lieder of 1900-1901, he bid a protracted fond farewell to Wagnerian Romanticism.

It is a leave-taking on the grandest of scales.

The texts, German translations from the Danish poetry of Jens Peter Jacobsen, deal with typical late-Romantic themes: love/death and redemption. The setting is a veritable music drama of two hours' length, complete with huge orchestra, chorus and soloists, a web of leitmotivs, and a kind of continual heaving and throbbing. It is a masterpiece, no doubt, but it makes the most continuous demands on performer and listener alike. The grand and almost luridly romantic aspects of this work are not the sort of artistic expression that one associates with Pierre Boulez, but in fact he handles the music very well in his new performance on Columbia. Clarity, directness, and a sensitivity to timbre seem to be what this work needs if it is not to bury itself in its own avalanches of sound. All that done, the emotional content somehow manages to take care of itself.

The interest of Herbert von Karajan in the music of his world-famous Austrian compatriots is, in itself, a footnote to the history of music. Karajan came to the music of the modern Viennese school only in recent years and then largely through the early romantic and expressionist works. It is this early music that is well represented in the four-disc set from Deutsche Grammophon, although there is a good sampling of later works as well. Of Schoenberg we have the works that immediately preceded and followed Gurre-Lieder Verklarte Nacht and the tone poem Pelleas and Melisande (this symphonic interpretation of Maeterlinck appeared several years before Debussy's operatic version)-as well as the Orchestral Variations of 1928, one of the most accessible of Schoenberg's twelve-tone works. Berg's Three Orchestral Pieces, Op. 6, are a kind of epitome of early Expressionism; the Lyric Suite music is the composer's own string-orchestra arrangement of three of the movements of the quartet original. Finally, the set includes the early Webern Passacaglia, still late-Romantic in language; the Five Movements, Op. 5 (arranged for string orchestra by Webern himself), and the Six Orchestral Pieces, Op. 6, both in Webern's most intense and aphoristic expressionist style; and the Op. 21 Symphony, one of the best-known but, to my ears, driest of twelve-tone pieces.

ODDLY enough, I don't find Karajan's versions of the more romantic music terribly convincing. He shares a certain fondness for detail and clarity with Boulez-the DG recordings are models of clarity and good acoustical sense-but he does not convey the passionate surge or, indeed, the large formal shape of a work like Pelleas. Now, I am the first to admit that Boulez is no ultra-romantic, and yet it seems to me that the expressive shape of a difficult work such as the Gurre Lieder comes across very well under Boulez's care, while, in spite of many beautiful details, Karajan's Pelleas seems amorphous, its emotional impact dulled. Berg and Webern fare much better, particularly the latter. Ironically, Karajan and the Berlin musicians are at their most impressive in the stark intensity and brevity of Webern's expressionist music. The Orchestral Pieces, Op. 6, one of Webern's most impressive accomplishments, are particularly strong. Even the Symphony, not one of my favorites, has an unexpected delicacy and nuance. How strange to find Boulez successful in a large-scale romantic work and Karajan excelling at atonal miniatures! A very special and beautiful performance of Verkliirte Nacht, far outclassing Karajan's in finesse, quality, and depth, comes from an unusual source: the Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields directed by Neville Marriner.

This conductor and orchestra continue to astonish me with their versatility. The Webern and Hindemith performances that accompany Verkliirte Nacht on the Argo disc are equally sensitive.

Schoenberg's Chamber Symphony of 1906, one of the most difficult and overbearing works of the transitional period, appears on Atlantic's Finnadar label in an excellent performance by an ensemble of topnotch New York musicians directed by Gunther Schuller. This performance succeeds in catching both the details and the long line of a work that has repeatedly resisted attempts at clarification. Unfortunately, the dry, studio sound of the recording will put some potential listeners off. Nevertheless, this performance succeeds in revealing more of this notoriously difficult piece than any other I know. The record also features a very attractive performance of the lush Berg Sonata by Turkish pianist Idil Biret and a lively, un-expressionistic interpretation of the Webern Five Pieces, Op. 5-the warhorse of atonal Expression ism!- previously issued on Atlantic.

SCHOENBERG, although not himself a pianist, produced a number of important works for the medium-his first atonal music and his first twelve-tone music appeared in piano works--and, since his collected piano works fit neatly on a twelve-inch disc, several outstanding interpreters of twentieth-century music have taken up the challenge. The latest is Paul Jacobs, for many years one of the leading new-music interpreters in Europe and America.

His readings on Nonesuch are strong, cool, and revealing, penetrating the "climate" of the music. Indeed, Jacobs has gone so far as to restudy the problems of textual accuracy in the printed editions, treating Schoenberg exactly like Beethoven or any other past master-which is, of course, exactly what he is.

- Eric Salzman

SCHOENBERG: Gurre-Lieder. Jess Thomas (tenor), Waldemar; Marita Napier (soprano), Tove; Yvonne Minton (mezzo-soprano), Wood Dove: Kenneth Bowen (tenor), Klaus the Fool; Siegmund Nimsgern (baritone), Peasant; Gunther Reich (speaker); BBC Singers; BBC Choral Society; Goldsmith's Choral Union; Gentlemen of the London Philharmonic Choir; BBC Symphony Orchestra, Pierre Boulez cond.

COLUMBIA M2 33303 two discs $13.98.

SCHOENBERG: Pelleas and Melisande, Op. 5; Verklarte Nacht, Op. 4; Variations for Orchestra, Op. 31.

BERG: Three Orchestral Pieces, Op. 6; Three Pieces from Lyric Suite.

WEBERN: Passacaglia for Orchestra, Op. 1; Five Movements, Op. 5; Six Pieces for Orchestra, Op. 6; Symphony, Op. 21. Berlin Philharmonic, Herbert von Karajan cond. DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 485/6/7/8 four discs $31.92.

SCHOENBERG: Verklarte Nacht, Op. 4.

WEBERN: Five Movements, Op. 5.

HINDEMITH: Five Pieces, Op. 44, No. 4. Academy of St. Martin-in-the-Fields, Neville Marriner cond. ARGO ZRG 763 $6.98.

SCHOENBERG: Chamber Symphony, Op. 9. Chamber ensemble, Gunther Schuller cond.

BERG: Piano Sonata, Op. 1. Idil Biret (piano).

WEBERN: Five Movements, Op. 5. Quartetto di Milano. FINNADAR SR 9008 $6.98.

SCHOENBERG: Three Piano Pieces, Op. 11; Six Little Piano Pieces, Op. 19; Piano Piece, Op. 33a; Piano Piece, Op. 33b; Five Piano Pieces, Op. 23; Suite for Piano, Op. 25. Paul Jacobs (piano). NONESUCH H-71309 $3.98.

Also see: