By Julian D. Hirsch

As an audio component, the phono cartridge has a somewhat ambiguous status. For some it is a mere afterthought, "the thing with the needle" at the end of the tone arm that they paid a penny extra for when they bought their turntable. But the in formed consumer knows that the performance of the cartridge is crucial to the long- and short-term quality of record reproduction. The truth is that regardless of the quality of the rest of the system, the ultimate "sound" of a phonograph record can be no better than the performance of the cartridge permits. On the other hand, almost all cartridges sold for use in high-fidelity component systems are good enough to ex tract reasonable quality from the majority of records. But because audible differences between cartridges are usually subtle (which is not to say insignificant) what is heard is therefore open to highly subjective interpretation.

Much of the mystique that has grown up around the phono cartridge arises from the fact that it has a well-nigh impossible task to perform, yet it man ages to function with remarkable near-success. Though totally accurate and complete measurement of all the factors that control the sonic performance of a cartridge is probably not beyond technology's means, we aren't quite sure about what to measure--or the significance of the measurements we do make. This, of course, invites the exercise of personal opinions and prejudices. All cartridge manufacturers are fully aware of the numerous factors that complicate design. To note a few examples (in typical engineering language): torsional and transverse resonances in the stylus cantilever; interaction between the effective moving mass of the stylus system and the record's plastic compliance; the pros and cons of various transducing systems (the part of the cartridge that converts the physical stylus motion to an electrical output signal); and many more. This is not the place to catalog all these difficulties or the ingenious ways cartridge designers have found to get around them. Instead, what we're seeking is a sensible approach to cartridge buying that takes these problematic factors into account where they count.

CARTRIDGES are analogous to loud speakers in their function, both being electromechanical transducers, though operating in opposite directions. As is true with the speaker, cartridge design involves considerable art in combination with science. Also as with speakers, each cartridge design involves certain "trade-offs" that have been made to achieve particular performance goals. What meaning do these compromises have for the cartridge buyer, and how much influence should they have on his thinking before he goes about selecting a suitable cartridge for his music system? The answers to these questions will be more useful with the help of a little background information, especially about the types of cartridges available and their key features.

Cartridge Types

Almost all high-quality cartridges are magnetic, and they depend on variations in the strength of a magnetic field impinging on a coil of wire to generate an output voltage. The majority use fixed coils having hundreds of turns of fine wire. In moving-magnet cartridges, a tiny magnet on the stylus cantilever (the minuscule metal tube or solid bar that connects the diamond tip at one end to the generating assembly at the other end) wiggles about under the influence of the stylus motion, thus inducing a voltage in the fixed coils. In moving-iron cartridges (also known as variable -reluctance), the magnet (or magnets) is more powerful and is fixed in the body of the cartridge. A piece of magnetic material (not an actual magnet) is moved by the stylus system to vary the distribution of magnetic flux between the fixed coils. A subcategory of the moving-iron design is the "induced -magnet" type, in which the magnetic flux from one or more fixed magnets is induced into a magnetic element attached to the cantilever.

Most major cartridge manufacturers use one of these generating systems throughout their entire product line. Although each type has its theoretical advantages, the degree to which they are realized in practice varies with the manufacturer.

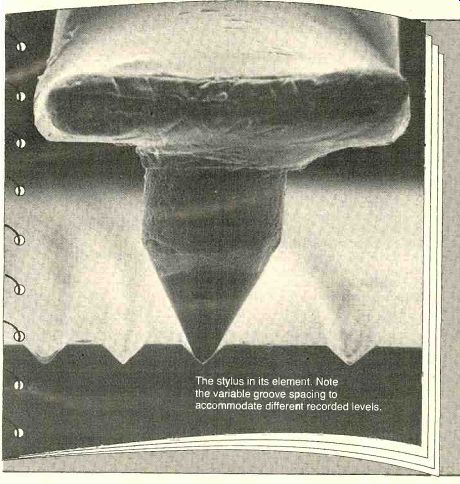

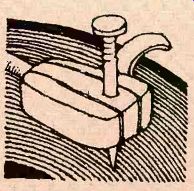

--------The stylus in its element. Note the variable

groove spacing to accommodate different recorded levels.

For many years, special sonic qualities have been attributed to the moving-coil cartridge. Although there may be a very slight theoretical advantage (in lower distortion) to the movement of a coil in a fixed magnetic field (as op posed to the variation of a field through a fixed coil), the moving -coil cartridge has compensating disadvantages. The need to wind an extremely small multi -turn coil (actually, two coils at right angles to each other) on a tiny bobbin makes moving -coil cartridges some what more expensive than most other types. Their output voltage is usually much lower than that of other magnetic cartridges (with a few notable exceptions), and in most cases a special step up transformer or a "pre-preamplifier" or "head amplifier" is needed to increase the signal output to the point where it is compatible with the phono input requirements of typical preamplifiers. These accessory devices, in addition to being expensive, can de grade the signal-to-noise ratio of the system if not carefully designed and in stalled. Finally, stylus replacement usually requires return of the entire cartridge to the factory or to an authorized service facility.

In spite of these negative aspects, the fact remains that the moving-coil cartridge is today more popular than ever, and it is considered by many record-playing purists to be the best avail able type. At least two explanations come to mind (there are doubtless more). First, some moving-coil cartridges have a relatively short, direct coupling from the stylus to the coils, minimizing the effects of cantilever resonances on performance. Second, other types of magnetic cartridges are designed with a complementary action between their mechanical stylus resonance and the electrical resonance of their generating systems (determined by the interaction of the coil inductance with the total circuit capacitance) to produce a flat overall frequency response. When properly executed this can result in an impressively flat measured response curve, but it does not eliminate the effects of the mechanical stylus resonance (usually in the upper most audible octave or just above it).

The process is analogous to attempting to eliminate a speaker resonance with frequency equalization; the response curve can be flattened, but the resonance (with many of its side effects) is still there. Some people claim that this is responsible for a variety of audible flaws in record reproduction; others are less positive of its audible significance.

No one denies, however, that the situation exists; the only argument is about its importance to the listener.

Moving-coil cartridges, on the other hand, have very little coil inductance; their response is therefore essentially independent of external loading conditions. Thus the ultimate frequency response of a moving-coil cartridge is determined, for better or worse, by its mechanical performance; there is no possibility of masking its mechanical characteristics-resonances and all with electrical equalization. For flat frequency response a moving-coil cartridge's mechanical performance must be intrinsically very good, and some believe this counts in terms of the sound you hear.

There are only a few nonmagnetic cartridges available to the quality -conscious phonophile. Because of their total lack of winding inductance, they have the same quality of independence from external loading that characterizes moving-coil cartridges. Among the better known is the electret cartridge (manufactured by Micro Acoustics), which uses small capacitive elements to produce a voltage when "stressed" by the stylus.

The Stylus

A large part of a cartridge's performance (perhaps the most important part) is determined by something outside the cartridge body itself: the stylus. This is a carefully shaped and polished piece of diamond almost too small to see with the unaided eye. It must faithfully fol low the microscopic undulations of groove walls whose scale is minute even compared to that of invisible dust parti cles. This is the almost impossible task mentioned earlier, since it is not reason able to expect a stylus tip whose dimensions are larger than the recorded wave length to follow the groove modulation accurately. In spite of this, the stylus manages to trace the complex record groove with remarkable accuracy.

Elliptical styli, now common at all but the lowest price levels, present a smaller radius (that is, a "sharper" edge) to the groove wall, and this improves the tracing of high frequencies. A variation of the elliptical stylus is used in CD-4 cartridges, which must re produce frequencies up to 45,000 Hz more than twice the highest frequency usually found on stereo records. These special shapes, known by various names such as Shibata, Pramanik, Quadrahedral, Hyperbolic, etc., not only have a very small edge radius to trace ultrasonic frequencies; they also have an elongated contact span in the vertical direction that distributes the tracking force over a larger area of the groove wall in the interest of reducing record wear.

THE question of how to select a cartridge for your own system is no easier to answer definitively than the question of what speaker to buy or which neck-tie; in all three cases subjective factors are disconcertingly significant. How ever, there are some guidelines that, if followed, can help prevent an expensive mistake.

Tone Arm and Tracking Force

The phono cartridge is as dependent on its tone arm as the speaker driver is on its enclosure. Fortunately, the matching of a cartridge to a tone arm is not nearly so critical as the speaker case, but a serious mismatch can be as damaging to the sonic result as an ill-designed enclosure.

If, like most people, you buy an integrated record player, the installation instructions will often specify a range of tracking forces over which the unit's arm will operate properly. Even if no such information appears explicitly, it can sometimes be inferred with reason able accuracy from the range of tracking-force adjustment provided by the arm. Make sure that the recommended force range of the tone arm encompasses the range of forces suggested by the cartridge manufacturer. Cartridges are specified over a range of forces (0.75 to 1.5 grams, for example) for several reasons. In a well-designed tone arm the cartridge can operate closer to its minimum rated force than in an arm having excessive pivot friction, in correct anti -skating compensation, or so much mass that it cannot negotiate the warps and ripples of an average record. In an inadequate arm extra force is needed to keep the stylus in reliable contact with the groove walls.

The tracking force of a cartridge is also related to the maximum recorded level it is to play. A record with low-to-moderate recorded levels can be tracked by almost any cartridge used at its minimum force. However, some records with extremely high groove velocities can tax the abilities of the finest cartridges used at their maximum rated forces. This is why the test records used by the laboratories to evaluate cartridges include extremely high velocity sections beyond the capability of practically any cartridge to track with out distortion. Obviously, one cannot determine the limits of performance of a component without having a signal source that exceeds those limits.

Unless you have a good reason for doing otherwise, it is a good policy to operate any cartridge slightly above its recommended minimum tracking force (but never beyond the rated maximum force). The difference in record or stylus wear compared to operation at the minimum rated force will be small or insignificant, but the chances of having your musical enjoyment (as well as the records themselves) ruined by the "shattering" sound created by mis tracking (the stylus' loss of secure con tact with the groove wall) will be less.

If you study the specifications and prices of cartridges carefully, you will find that the range of tracking forces tends to go down as the price goes up, although there are numerous overlaps and a few seeming contradictions. Low tracking force is desirable from the standpoint of record and stylus wear.

Although it does not, in itself, have much to do with sound quality, a number of related parameters (such as stylus mass, which must be low to permit low tracking force) have a lot to do with quality. In fact, the recommended tracking force is about as good a guide to overall cartridge quality as any published rating (the lower the better, in general), assuming that the recommendation is honest and accurate. Note, however, that the tracking forces of CD -4 cartridges (if not the pressure on the groove walls) are often 50 to 100 percent greater than those for stereo cartridges, and for good reason.

As with all the other components of a music system, it makes sense to match the quality of the cartridge to that of the record player. Even if a $200 moving -coil cartridge can be used in your $100 record player, you would probably be better off selecting a cartridge in the $30 to $40 range. This is especially true if the rest of your system includes a modestly priced amplifier or receiver and compatible speakers in the under-$100 range. It is unlikely that the investment in an expensive cartridge would pay dividends in sound quality unless the rest of the system were of comparable quality.

It should be equally obvious that a low -price cartridge (in today's market, one with a list price of $30 or so) will usually not match the sound quality of a more expensive one. Such a high -tracking -force cartridge is suitable for a low -price record player, but it would be a poor choice for a $300 direct -drive unit, for example. In the $50 to $60 range, cartridges become very good, often rivaling much more expensive models, and they can be used to advantage in record players selling for $150 or more. If you decide on a deluxe cartridge, one priced from $70 to $100 or more, be prepared to make a comparable (substantial) investment in a top quality record player as well as in an equivalent amplifier and speakers (note that top quality does not inevitably mean top price, however).

Cartridge Specs

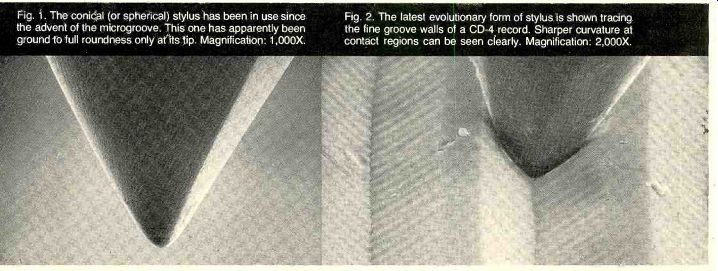

---------- Fig. 1. The conical (or spherical) stylus has been in use

since the advent of the microgroove. This one has apparently been ground to

full roundness only at its tip. Magnification: 1,000X. Fig. 2. The latest

evolutionary form of stylus is shown tracing the fine groove walls of a CD-4

record. Sharper curvature at contact regions can be seen clearly. Magnification:

2,000X.

Do not be overly concerned about cartridge performance specifications.

They can be used to compare models from a single manufacturer and as a rough guide otherwise, but the lack of universal standards for testing and rating cartridges makes it a risky business to compare competing brand models merely on the basis of advertised ratings. Any cartridge will be rated to cover the audible frequency range with a moderate variation (perhaps ±3 to ±4 dB on lower -price models to as little as ±1 dB on some of the finest ones). The same situation exists with crosstalk, or channel separation, which should be at least 20 dB in the mid -range (and preferably at least 10 dB in the 10,000- to 15,000 -Hz range, where it is rarely specified). Almost any cartridge can meet these requirements, and some are far better, but that does not mean that their separation is audibly better.

The general similarity in rated performance of many cartridges suggests that they might sound pretty much alike. To a first approximation they do, which makes the task of selection both easier and more difficult: easier be cause it is harder to make a serious mis take (provided the tracking -force rating of the cartridge is compatible with that of the tone arm); more difficult because the subtle audible differences which may be important to you simply may not appear on the specification sheet at least not in any clear-cut manner. In other words, if you are truly critical in your sonic tastes, there is no substitute for listening for yourself.

Some of these differences, as de scribed by those who are able to hear and appreciate them, include such scarcely definable qualities as transparency, definition, a sense of "air" or ambience in the sound, superior stereo imaging, "sweetness," and the like.

You should be warned again that, as of the moment, these qualities are not susceptible of proof, they are heard differently by different people, and they may in fact often be an expression of un critical enthusiasm on the part of those who claim to hear them. This is not to denigrate the more esoteric, subjective aspects of sound evaluation. However, it is all too easy to "psych" one's self into hearing what one wishes to hear.

----------------------------

FOCUS ON STYLUS

THE phono stylus does its work in a world whose dimensions are so small that they defy the probing of ordinary optical micro scopes. Conventional photography simply cannot provide sufficient de tail or depth of field on this sub-Lilliputian scale, but the scanning electron microscope, a rather exotic laboratory instrument and re search tool, can-as the remarkable photographs (courtesy of Stanton Magnetics) on these pages amply demonstrate.

-Ralph Hodges

---------------------------

Since the final judgment is ultimately in the mind's ear, this is of course a perfectly reasonable basis for selecting a cartridge--or any other component, for that matter. But don't expect to find these qualities defined in laboratory test reports or the manufacturers' numerical specifications (as opposed to advertising literature).

Cartridge and Amplifier

So far, we have been considering only the mechanical compatibility of the phono cartridge with the tone arm and a bit of the economic basis for cartridge selection. There is, in addition, an electrical interface to be considered, that between the cartridge and the amplifier. A considerable degree of standardization exists here, fortunately, making for easy matching of most cartridges to most amplifiers, but you should know that there is at least the outside possibility of an incompatible combination.

As pointed out earlier, magnetic cartridges in general depend on the load capacitance and resistance to equalize their outputs electrically for flat frequency response at high frequencies.

This load is provided by the phono-cartridge inputs of the amplifier as well as the cables that connect the cartridge to them. A cartridge termination of 47,000 ohms (nominally 50,000 ohms) has long been accepted as a standard. Some amplifiers can be switched to load the cartridge with other resistances (such as 25,000 or 100,000 ohms) that result in a slight modification of the cartridge's response.

In recent years we have become more aware of the importance of the capacitive part of the cartridge load in determining final response. It is not very critical, and most cartridges work well with the typical circuit capacitance of 250 to 300 picofarads (pF). A few cartridges, however, should have a load of 400 to 500 pF for best results.

Most CD -4 cartridges, on the other hand, should be loaded with not more than 100 pF (special cables are used to connect the tone arm to the amplifier to achieve this). (overleaf) ...

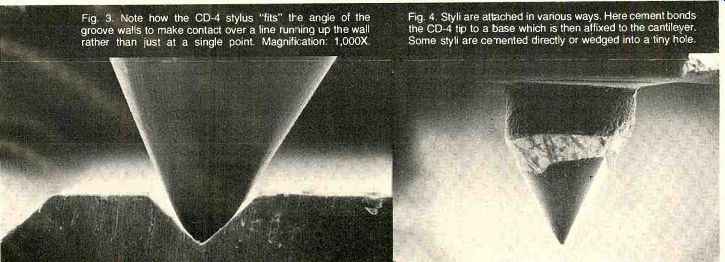

--- Fig. 3. Note how the CD -4 stylus "fits" the angle of

the groove walls to make contact over a line ruining up the wall rather than

just at a single point. Magnification: 1,000X. Fig. 4. Styli are attached

in various ways. Here cement bonds the CD-4 tip to a base which is then affixed

to the cantilever. Some styli are cemented directly or wedged into a tiny hole.

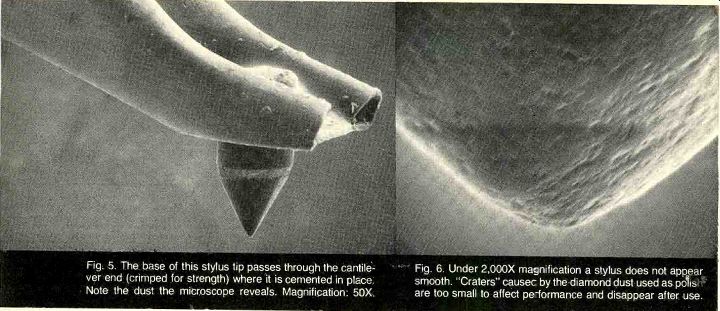

----- Fig. 5. The base of this stylus tip passes through the cantilever

end (crimped for strength) where it is cemented in place. Note the dust the

microscope reveals. Magnification: 50X. Fig. 6. Under 2,000X magnification

a stylus does not appear smooth. "Craters" caused

by the diamond dust used as polish are too small to affect performance and

disappear after use.

Unfortunately, the consumer has no way of knowing what the effective load capacitance is, and it can vary widely depending on the record player's arm wiring, the connecting cables, and the amplifier's own input capacitance. For most purposes you can use the record-player manufacturer's figures for his arm -wiring capacitance as a guide, and our laboratory test reports on tone arms always include an actual measurement of this parameter. Since the audible effects of capacitance changes are usually about as subtle as those distinguishing the sound of one cartridge from another, many people simply ignore the matter. For others, it can be crucial. For example, the cartridge-coil inductance, interacting with some preamplifier circuits, can cause a gain (or a loss) of several decibels in the range of 10,000 Hz and well beyond.

-----------------

INTRODUCING THE DAZZLETRACK MODEL PC-1 PHONO CARTRIDGE

ENTIRELY a figment of our journalistic imagination, the Dazzletrack PC-1 has been created to provide some in sight into the technical language used today in describing phono-cartridge performance. A study of its thoroughly mediocre specifications (and the explanatory footnotes below them) should give the reader a general under standing of what the numbers-singly and collectively--can tell him about a cartridge and what they cannot.

There are cartridge manufacturers who have come up with a few specifications that are all their own, at tempts to define aspects of performance they consider particularly important. In some cases they have backed their special ratings with impressive re search and validation, so that any con sumer can see for himself what is being measured, how, and why. The Dazzletrack Company tends to be 'a little conservative in this respect, listing only one specification not found on most other spec sheets (see below), and that one a bit obscure and of dubious value.

Also remember that, so far, no one in the world outside of Dazzletrack knows how these specifications were derived, since there are few standard test procedures in the phono-cartridge world. Perhaps they can be compared directly with the specifications of other manufacturers but, then again, perhaps not.

1. Frequency response: 10 to 22,000 Hz ±4 dB. Hardly an imposing specification. A frequency-response curve would be helpful in determining whether the largest variations occur at the frequency extremes (possibly tolerable) or in the middle of the audible-frequency range (undesirable).

2.. Channel separation: 15 dB. No frequency is given, so we can assume that the test frequency was 1,000 Hz.

Stereo separation of 15 dB is probably adequate, but there will no doubt be a tendency for separation to deteriorate at higher frequencies.

3. Channel balance: within 3 dB. This means that the outputs of the two channels are matched to within at least 3 dB of each other. This specification should be directly comparable with those given by other manufacturers. However, it is not of overwhelming importance, although you may have to offset your balance control to compensate for channel -balance inadequacies.

4. Stylus: 0.3 x 0.7 -mil elliptical. The stylus has an elliptical shape with a relatively mild edge curvature. Still, for tracking forces above 2 grams, a less "sharp" 0.5 -mil spherical stylus might be expected by some to result in reduced record wear.

5. Compliance: lateral, 12 x 10^-6 cm/ dyne; vertical, 8 x 10^4 cm/dyne. Comparatively low static -compliance figures in the lateral and vertical directions indicate that the stylus is rather stiff and might have trouble tracking large low-frequency groove modulations successfully.

6. Effective tip mass: 0.8 milligram. A high effective tip mass (and this is high for a premium cartridge) indicates that the stylus has plenty of inertia, and hence will probably have difficulty negotiating high-velocity high frequencies without mistracking. Increasing the tracking force should help up to a point, but it is not certain how much.

7. Recommended tracking force: 1 to 3 grams. Considering the PC -1's low compliance and high tip mass, a 1 -gram tracking force seems optimistic. Per haps the manufacturer means the stylus will stay in the groove at I gram, but so might a safety pin in a good tone arm. The wise user should expect to apply something close to the 3-gram maximum. Even then, state-of-the-art performance cannot be expected on heavily recorded passages.

8. Output: 5 mV at 3.54 cm/sec. The cartridge yields plenty of output from a reference recorded velocity. In fact, it might be too much for a phono preamplifier that lacks a generous overload margin.

9. Recommended load: 47,000 ohms. This is the standard load provided by virtually all phono-preamp inputs. CD-4 cartridges generally specify a 100,000-ohm load, which is the termination provided by the CD-4 demodulators into which they are presumably plugged.

10. Optimum total capacitance: 250 pF. The total capacitance is the sum of the capacitances of the phono inputs plus the interconnecting cables and arm wiring. You may have to make some inquiries to find out what these are in your system, but even a sizable mis match will not make a great audible difference.

11. Inductance: 650 millihenries. From the inductance of the coils an expert might be able to judge how the frequency response of the cartridge will change with different resistive and capacitive loads, but that is a job for an engineer, not an audiophile.

12. D.C. resistance: 950 ohms. Likewise, from the d.c. resistance of the cartridge and certain known characteristics of the phono preamplifier certain generalizations about the noise performance of the system might be made. But, again, by experts only.

13. Vertical tracking angle: 20 degrees. This is now standard, and it is gradually superseding the previous 15-degree standard. The difference between 15 and 20 degrees will have no practical significance for most audio systems, however.

14. Elastic rebound characteristic (ERC): 4.7 millimeters. A little some thing extra from Dazzletrack: a spec no one else gives you. This one is meant to indicate how high the cartridge will bounce when dropped onto a flat marble surface from a distance of 1 meter. Clearly the PC -1 would not make a good golf ball. But be on the lookout for other unfamiliar specifications and acronyms that may supply valid and useful information once they are understood.

15. Weight: 10 grams. The PC -1 is a hefty little package, and its ample mass could very well undo the benefits of an expensive low -mass tone arm. Also, some arms do not have a sufficiently heavy counterweight to balance such a cartridge. All in all, it would be best to consider using the Dazzletrack PC -1 cartridge only as part of a modest sys tem-if at all!

-Ralph Hodges

----------------------------

Nowadays, amplifier phono inputs usually carry both a sensitivity and an overload rating. The latter is the maximum input the phono preamplifier can tolerate before overload distortion occurs. The former is the input, in millivolts at 1,000 Hz, required to drive the amplifier to its rated power output (in our lab tests, we define the sensitivity as the input needed for a reference power output of 10 watts, which is generally lower than the rated -output sensitivity). There can be a wide latitude in matching this figure with the cartridge's rated output, which is usually based on a standard reference recorded velocity (perhaps 3.5 to 5 centimeters per second). In most cases, a two-to-one mis match in either direction can be tolerated, and with a good amplifier the permissible spread between the two volt ages can be much greater than that. In other words, if the cartridge's nominal output is 3 millivolts, it can almost certainly be used with amplifiers whose phono sensitivity is between 1.5 and 6 millivolts. In fact, the only problem likely to be encountered with an even higher (numerically) sensitivity rating is a slightly poorer signal-to-noise ratio.

The overload rating of an amplifier, on the other hand, should be at least twenty times the cartridge's rated out put; many feel it should be even larger.

One of the few areas of possible trouble in matching cartridges and amplifiers lies in the use of the lower -price cartridges (whose outputs can be as high as 7 to 10 millivolts) with inexpensive amplifiers whose phono sections can sometimes be overloaded by signals as low as 50 or 60 millivolts (fortunately, even the least expensive amplifiers these days are usually better than that). Another is the use of a typical moving-coil cartridge whose output into the preamplifier may be only a small fraction of a millivolt. In this case, a step-up transformer or booster amplifier may have to be used between the cartridge and the amplifier to obtain an adequate loudness level and signal to-noise ratio. A pre-preamplifier can be quite expensive, an inferior one could noticeably increase the hiss level, and if transformers are used in stead, they must be carefully positioned to avoid hum pickup.

Quadraphonic Cartridges

Although four-channel stereo is no longer as prominent in audio headlines as it has been, the reports of its demise are somewhat exaggerated. Matrixed quadraphonic records are, as far as disc -tracing is concerned, no different from stereo records, and the cartridge requirements are therefore the same as for stereo. "Discrete" CD -4 records, on the other hand, must be played with a special cartridge--even in two-channel stereo, if you wish to avoid destroying the ultrasonic content that is responsible for their four-channel performance. This means that the cartridge should have a Shibata or a similarly shaped stylus. Some four-channel cartridges are quite expensive, and in many cases their stereo performance is not on a par with that available from much less expensive stereo cartridges.

On the other hand, a few recent ones most of them still costly-are truly excellent stereo reproducers as well. Let your present and future listening plans be your guide here. If you are positive that discrete four -channel discs are not for you, you can save a lot of money and perhaps get better sound by selecting one of the better stereo cartridges.

But if you suspect you'll want your system to grow along with new developments, a CD-4/stereo model might be worth considering right now. Certainly it cannot impair your compatibility in the future.

Also see:

EQUIPMENT TEST REPORTS: Hirsch-Houck Laboratory test results on the: JVC JR-S600 AM/FM stereo receiver, Marantz Model 1250 integrated stereo amplifier, KLH Model 354 speaker system, and Micro Seiki DDX-1000 turntable and MA-505 tonearm

CAN YOU REALLY HEAR THOSE HI-FI SPECS? It all boils down to dynamic range and achievable loudness [Jan. 1976]

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)