THE CASE FOR MINIMAL MIKING: The "back to realism" movement is

invading the nation's recording studios.

By David Ranada

In the "good old days," when all recordings were analog, direct-to-disc, and mono, before tape, stereo, and now digital recording techniques rolled over everything like a succession of steam rollers, the goal of a quality audio system (which includes the recordings played on it) was to produce in the listening room the illusion of "a live performance as heard from the best seat in the house," and the watchwords were "accuracy" and "realism." Nowadays, however, listener orientation has changed somewhat in this regard.

Many people now want only "good sound" out of their stereo systems, ac curacy and realism are incidental, and "hi-fi" is used in its original sense only by the most tenaciously unreconstructed audiophiles.

These days, most listeners seem to forget that almost every recording of whatever type of music ("documentary" recordings are one obvious exception) can be seen as an attempt either (1) to re-create a "live" performance or (2) to realize the potential of an independent medium of musical communication only incidentally related to the sound ordinarily produced in live performance. These two points of view lie at the heart of any discussion of recording techniques, and they particularly affect the question of how many micro phones are needed to do a particular re cording job properly. But studying and weighing the various arguments on both sides will not produce any kind of "winner" in the "purist"-vs.-"multi-mike" debate. Indeed, there can be no winner in such an aesthetics-centered argument except in the purely commercial sense of which approach ends up selling the most records. However, a brief examination of some of the problems involved in miking a recording session "properly" should help you decide just where your own sonic prejudices place you in regard to a controversy that is currently taking up a good deal of discussion time in some of the nation's recording studios.

Recording as Re-creation

If a recording is represented as being "high-fidelity," one may reasonably expect it to be a faithful re-creation of an acoustical event that occurred at another time in another place. Unfortunately, an exact re-creation (one perceptually indistinguishable from the original) is still not possible even with to day's advanced technology, the success of many live-vs.-recorded demonstrations notwithstanding. (Those demonstrations usually use a large room for playback and an anechoic chamber for the original recording-not quite the same thing as re-creating concert-hall sounds in arbitrarily selected home listening rooms.) Furthermore, an exact re-creation of a performance would not admit of such musically useful (some times even vital) processing as tape splicing.

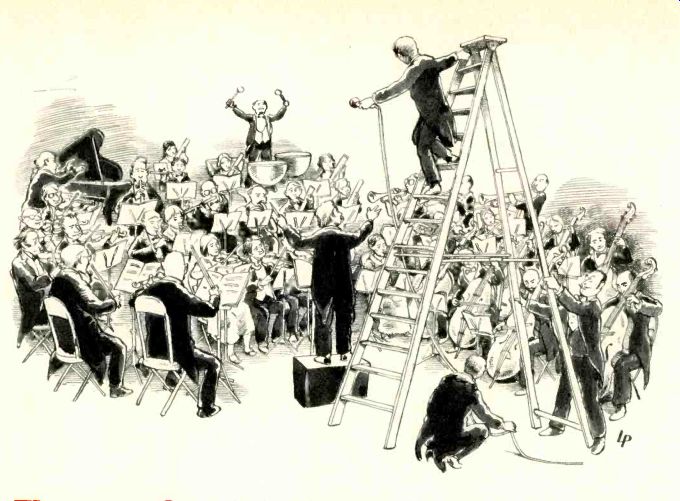

What modern stereo systems can do, and have been able to do for some time with varying degrees of success, is to create a plausible acoustic illusion of a musical event that could have occurred somewhere else at another time. Often the sound will not even be close to that heard from the best seat on the ground floor of a hall, or even from the best balcony seats, but will approximate what might be heard by someone sit ting, say, atop a twenty-foot ladder just behind the conductor. Regardless of the "viewpoint," however, home stereo systems can create the illusion of a realistic sonic situation, though it might be one not likely to be encountered in everyday life.

Of course, microphone techniques have a great deal to do with the believability of any sonic illusion, and it is here-in the creation of a plausible acoustic illusion-that I find close-in multimike techniques begin to show their weaknesses. These faults can be heard in varying degrees on almost every recording made with such techniques; they destroy the hi-fi illusion either by making it (1) internally inconsistent or (2) simply unrealistic.

Many record critics and home listeners seem to be indifferent to how close miking works against sonic realism.

Others, though they sense something improper about a multimike production's sound, often can't pin down exactly what is wrong. A number of sonic characteristics of multimike productions work against realism, and I believe they have tremendous musical consequences.

1. Multimiking can radically change instrumental timbres from those of normal "concert-hall sound." Most instruments do not radiate sound with the same intensity in all directions at all frequencies; they are not, in other words, omnidirectional. From the relatively distant perspective of a con cert-hall seat, even one fairly close to the stage, reflections from the stage walls and the hall surfaces combine with the direct sound of the instrument to create a different sound than would be received by a close-in directional microphone. Even the addition of reverberation to the mixed-down signal may not restore a realistic sound, especially if it is artificially generated from the close microphone's signal.

2. String vibrato, whose purpose is to lend richness to the sound of large string ensembles, can have its purpose defeated by close microphoning. A near-field microphone re moves the hall's blending effect on the individual instrument's vibrato, with the result that the listener can detect each waver from each player individually. This kind of sound is hearable from the first few rows of a con cert hall, but those seats are generally regarded as inferior. Mixed-in reverberation can help disguise some of the waver, but not always.

3. Slightly sloppy attacks, which would be relatively unnoticeable in the concert hall, again because of the architecture's "smearing" effect on short-term sonic events, can be glaringly obvious in multi-mike recordings.

4. Some orchestral players-percussionists, for example-make it a habit to anticipate the conductor slightly because of their distance from the podium and the audience.

A close microphone placement can make their entrances precede those of the rest of the ensemble slightly, an effect that is definitely not audible in the hall and is certainly unacceptable musically.

5. Reverberation, which is often added to individual tracks to correct for some of the unrealistic effects described above, can "pool" around an instrument in the final mix, making it seem to be coming from a different acoustical environment than the other instruments. Differing acoustical environments are sometimes necessary (off stage effects in opera, for example), but they should be prescribed by the composer, not the recording engineer.

6. Dynamic range can be falsified with a multimike setup. First of all, it is mathematically unavoidable that the more unrelated signals are added together, the poorer the ultimate signal-to-noise ratio (and re member that close-in mike signals are not very similar to each other since their purpose is to isolate each instrument or group).

Moreover, the dynamic range can be perceptibly degraded, since an instrument played pianissimo has a different lone color than one played fortissimo. Even if you turn up a recording of, say, a softly played oboe to fortissimo levels, you can still tell that it's being played pianissimo. The result would be a perceptual conflict between the actual loudness of the sound and the clues to the loudness it should have derived from the tone color of the instrument. This hap pens in multimike productions because the recording levels for each microphone are changed frequently as the music progresses to "correct" the balances.

7. Unless the musicians take great pains to remain quiet, close miking will result in an increase in musician- and instrument-made noise. Low-level sounds such as page turning, woodwind key clicks, and chair creaking can be exaggerated by close-in microphoning to distracting levels far above those heard in the hall.

8. Instrument locations and acoustical image size may be unrealistic. For example, multimike productions usually give a definite, stable, and small-size image location to the French-horn section of an orchestra.

Heard live, the horns' location is not always obvious, for the bells of the instruments point away from the audience. The audience mostly hears sound reflected from the back stage wall. You could hear where the horns are if you stood behind the orchestra, but then you'd lose all the brilliance of the string tone, which projects upward into the hall.

9. Finally, if the mixer controls are manipulated up or down enough to have an audible effect, instruments can momentarily assume an aural prominence they would never have in a live concert.

This little litany of sonic faults does not mean that plausible and realistic recordings cannot be made with multi-mike techniques, only that it becomes harder to achieve realism the more microphones you add. Trying to correct one fault usually leads to another. "Purist" microphone techniques (some of which are described in Bruce Bartlett's article on microphone placement) tend to preserve the auditory illusion of realism because the sound remains consistent; the image doesn't change while you are listening.

For myself, I am perfectly willing to let a record producer use all the micro phones, equalizers, artificial reverberators, and splices he wants to in recording a work not originally meant to be heard via recordings as long as the final result remains realistic. But that's a difficult goal to achieve with a multi-microphone setup. The true issue in the purist/multimike debate is not the number of microphones. Excellent, realistic recordings have been made with as few as one and as many as several dozen microphones. The question is whether a producer (possibly abetted by the performers) is justified in making an unrealistic recording, one that cannot claim to be a plausible re-creation of an actual performance.

Recording as New Creation

But there are those who would say that a recording does not have to be a re-creation-plausible or otherwise-of a "live" musical event, that recording is an independent medium of musical communication essentially different from concert-hall performances. This view is of course defensible-it is, in fact, the principal aesthetic basis of most popular-music recordings, the "originals" of which never existed before the making of the recordings and frequently could not be produced "live" anyway. It is also the basis of "classical" electronic music.

It is further argued that since recording is an independent medium, there is no reason not to manipulate recorded sounds. This too is unobjectionable-if the composition was intended expressly for the phonographic medium. But to use multimike techniques to change the balances and timbres of a composition conceived for the concert hall to balances and timbres that would be impossible without electronic assistance is something else again.

"Service to the musical composition" is often cited as the justification for sound manipulation beyond what is acoustically plausible. But this argument makes several rather questionable assumptions:

That the composer would have wanted his music "clarified" in such a way. Most classical music being as old as it is, this can rarely be determined, so it becomes a matter of musical interpretation. But if a producer makes interpretive musical decisions in the interest of "clarity" that result in unrealistic sound, then he should not complain if a music critic responds that "clarity" was not what the music required at that point. To clarify the waves of arpeggios that open Ravel's Daphnis et Chloe Suite No. 2 or that close Wagner's Die Walkure, for two examples, would not be a service to these compositions, for they require a wash of sound to make their effect, not individually heard polyphonic lines.

That the composer would not have changed the score himself if he knew it were to be presented through a recording. Mahler, for example, took infinite pains with his scores, revising them so they would "sound" in performance in a concert hall. Altering the sonic perspectives in a recording of a Mahler symphony to ones that would be impossible in a concert hall does violence to the composer's carefully calculated orchestration.

That the effect desired cannot be obtained without stepping out of the bounds of acoustical realism, that the musical line chosen for microphone emphasis could not be made audible with a "purist" mike setup or some adjustment in the actual instrumental performance. This cannot be proved unless simultaneous multimike and purist recordings are made at the same session.

Even then, a work reinterpreted "at the mixer" is just as likely to be missing other details that the producer (and/or conductor) has chosen not to highlight.

In effect, turning up one control is equivalent to turning down all of the others.

That the musical detail chosen for emphasis is significant enough to justify obscuring other, perhaps more important, musical lines. This, too, is a matter of musical interpretation.

That the listener is too musically unsophisticated to listen for himself and choose what lines he wants to pay close attention to. A recording that leads the listener by the ear turns what is already perhaps too passive an act into one requiring no effort at all. Listening should be a more dynamic enterprise than that! "...multimike recordings today are so frustratingly unrealistic that we have to listen to them as `electronic music' if we are to stand them at all."

FOR all the above reasons, I think it can be fairly argued that "activist" producers are adding another layer of interpretation to that of the musicians. Purists, I hasten to add, also add a layer of interpretation, but it is at most a thin varnish, not a heavy coat of paint. An analogy is sometimes drawn between a recording and a film of a concert. A cinema verite film of a concert, in which the camera remains fixed in position and perspective throughout, would be uninteresting and perhaps even exasperating to watch. But so are many so called film "interpretations" of concerts: the camera may not focus on what the viewer wants to see, just as the multimike producer may not be recording what the listener wants or needs to hear.

If the proper goal of a record producer is truly to serve the composition and I believe it is-the correct analogy is with a photographic reproduction of a painting. The photographer's job in such a case is not to "interpret" the masterpieces he photographs, but to make a "record" of them that is as ac curate and realistic as possible given the limitations of the medium. Granted, the reproduction cannot be perfect (the impasto will not be duplicated, for ex ample), and there is some unavoidable interpretation involved in the selection and positioning of the light, the choice of film and camera, but the approach is similar to the recording purist's search for optimum mike positions. With the right equipment properly used, the results in both cases can be tremendously exciting-witness some of the recent minimally miked recordings on the Telarc label and the spectacular reproductions Polaroid gets with its "Museum Camera." If photographers of paintings emphasized the "important" details in the masterpieces they document the way some audio producers do, we'd have Mona Lisa's grin stretching from ear to ear.

Audio Verite

There is, however, a way to listen to recordings that sets aside all questions of production procedures, type of music, or degree of realism or unrealism, and that is to listen to all recordings as if they were "electronic music" such as a tape piece by Stockhausen, a work of musique concrete by Pierre Schaeffer, or perhaps Walter Carlos' "Switched-on Bach" or Isao Tomita's " Bermuda Triangle." When you listen to such a disc or tape you are not hearing a "re corded performance" but a performance of a recording. Taken to its logical conclusion, this view implies that there are no such things as recorded performances, only electronic performances.

Whether the sound source is a synthesizer or "natural" instruments, the performance as such takes place only when you press the start button or cue the tone arm. The only "interpretation" is that introduced by your particular stereo system, your mood, or your listening room.

There is nothing ethically, legally, or musically "wrong" with listening to recordings this way. In fact, you can learn a lot about the internal workings of a complex piece of music by listening to an ingenious electronic realization such as "Switched-on Bach." But not all music is as durable under such treatment as Bach's, and there is no question that such recordings may be far from what the composer intended (they are certainly far from what was notated). Unfortunately, many multimike recordings today are so frustratingly unrealistic, artificial, canned, processed, implausible, calculated, pre-interpreted, re-interpreted, and un-spontaneous that we have to listen to them as "electronic music" if we are to stand them at all.

That doesn't strike me as much of a service to the musical composition or to the performers.

(Next month: Multiple Miking)

Also see:

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)