PRODUCTIVITY

By Dick Glass, CET

Why Measure Your Productivity?

By measuring the productivity, you can know how well your shop is operating. If the percentage is low, you can make plans to improve it. If it is okay, you can go on to more pressing problems. The methods recommended here can be used to measure the productivity in just a few minutes.

Figure 1

TABLE 1 -- Expected Productive Averages

Suppose your productivity is 70%. Or 80%. Or 90%. Probably you don't care what it is. After all, you're working at top speed, repairing radios, TVs, stereos, etc. There's no way you can improve, is there? Also, you've gotten along okay so far without knowing anything about productivity. So, why not spend all of your extra time studying new developments (such as VIR circuits or using spectrum analyzers) to improve your technical knowledge? It's logical that your increased knowledge will make your job easier and shorten the time of each repair. Therefore, you will obtain more benefits by studying technical subjects rather than by calculating some "useless" percentage of productivity. That philosophy sounds logical, but it is basically wrong.

Excuses

All of those reasons really are only excuses; although they contain some truth. You should continue to study the new technology, or your abilities will diminish when the new products need servicing. If you are an employee, your boss will spur you on to perform at a high peak level. Or, if you own the shop, the fear of starvation and bankruptcy keeps you working fast and long.

Nevertheless, if you have intentions or dreams of becoming wealthy, you have an imperative need to know how to calculate your own productivity, and also that of all your employees.

You're No Good With Figures?

Don't worry if you have little skill with mathematics. If you can add up a service invoice, then you can figure productivity. Only very simple calculations are involved. These are even easier, if you have a hand calculator.

Remember, productivity calculations are not "ratio analysis," P&L research, or any other forms of complicated drudgery. In fact, you'll find that it is easy and fun to do.

TABLE 2--Four-Man Shop Productivity ---- This box shows productivity for one week for the total shop as well as the individual technicians. The 50.7% percentage might be expected to be lower (perhaps 45%) for the entire year.

Benefits

There are several important benefits from knowing the exact productivity percentage of your shop:

1. You will think better of yourself.

When you don't know your productivity rating, you probably assume that it is low. After all, you do have "tough dogs" frequently, and they slow you down. Also, the paperwork and phone calls waste much of your time. Maybe you're embarrassed to admit that your average is four completed repairs per day. But, if you know your average productivity is 60%, and that 60% is darned good, you might start thinking more highly of your self.

2. You will improve. When you know what your average has been, you have a point of comparison. If your percentage is 35%, you will want to find ways to save time and increase that 35%. Later, when you measure it again, and find you have been successful in increasing the percentage to 40%, you know you're doing something right! That's progress.

3. You won't fight the wrong problem. What if you have a TV problem, and have no way of determining whether the defect is at the AC wall socket, in the TV chassis, or in the antenna system? You can waste time checking all three possible areas before finding the source of the problem. Of course, you are not that helpless. A "rabbit-ears" antenna can be substituted for the antenna system, and you can measure the voltage at the AC socket. After you know those are not to blame, you can go right to the TV chassis as the source of the defect. In the same way, suppose you don't know whether your financial problem is caused by: low labor charges; low productivity; or too-low pricing of parts.

Because you don't know for certain which is responsible, you are likely to waste precious time and energy trying to solve the WRONG problem. Many owners and managers assume that low productivity always is the culprit, and they try to corner more service jobs, which forces them to work longer hours. If your productivity is NOT bad, this approach is a vicious circle, making the situation worse. Find the real problem, and then work toward solving it.

4. Pride will return. No self respecting technician will watch his fellow workers out-produce him, without at least trying to catch up and surpass them. One facet of human nature is that good-natured competition gives zest to work. But without a rating system, this incentive is lost. Take advantage of this trait by posting the productivity percentages on the bulletin board for all to see. Or, if you want fantastic results, base each technicians wages partially on the average productivity!

5. More accurate pricing. Most service managers have serious questions about their prices. On one hand, they know their profits and wages both are too low. However, they frequently are confronted by customers who strongly suggest that the charges are too high. Of course, productivity is not the only factor determining your charges, but it is helpful to know if your productivity is average or above. If so, then your prices are not "high" because of poor efficiency.

These are five good reasons for wanting to know the productivity rating of your shop. You're convinced, I hope, so it's time to do some figuring.

Figuring Productivity

Calculation of productivity is easier for technicians than it is for most other job categories. For example, how would you figure the productivity of a hospital nurse? Should you count the number of patients and the number of "shots" compared with an industry norm? No! In this, and many other professions, the quality of the ser vice, the clean personal appearance, and a helpful attitude can be more important than any statistical aver age. In similar ways, the productivity of electronic technicians can be evaluated either by meaningless or important standards.

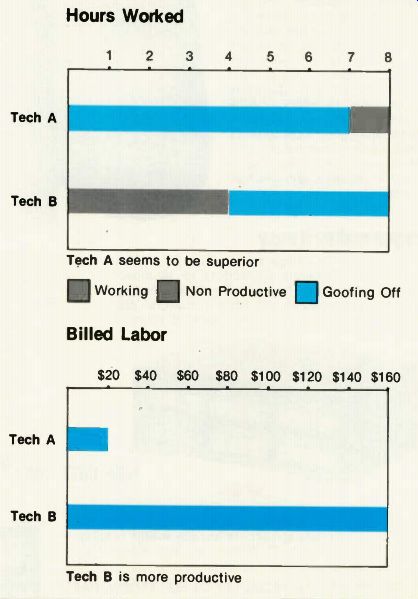

One way to measure the productivity of an electronic technician might be to spy on him from a hidden position as he worked at the bench. If he wastes one hour out of eight on breaks, personal phone calls, or "shooting-the-bull," then he might be considered as 87.5% productive. (Seven hours working divided by the eight hours he was paid for equals .875 or 87.5%). The method can show the percentage of time spent actually working. That allows you to identify a lazy tech; but does it help your profits? No, that's worthless information. Instead, you need to deter mine how productive he is, and not how many hours he works. Isn't a tech more valuable to his firm if he produces a dozen highly-profitable jobs in four hours (and goofs-off the other four), than if he works hard for the whole eight hours just completing one unprofitable repair? Study Figure I before you answer.

Base the productivity on dollars

Don't base the productivity rating on the hours spent, the hours worked, or the wages paid. Use only dollars paid the technician versus the dollars he brought in. That's the first rule of measuring productivity.

Use the hourly shop rate

The second rule for figuring productivity is: use the shop hourly rate of billed labor. Now, all shops attempt to charge a certain amount per hour. Even those that use some kind of "flat-rate" pricing (where a specific price is charged for certain repair functions) base it on the knowledge that some jobs take more (or less) time to complete than the average of all repairs. For instance, we expect that less is needed to repair a child's record player than to repair a color TV or a videotape recorder. Therefore, the phono repair might be priced at $15 on the flat-rate chart, while the VTR might have a flat-rate price of $90. Probably, the phono is estimated to take a half hour, compared to three hours for the VTR. In these two examples, your "hourly rate" is about $30.

It's okay to be uncertain

This is the third rule for figuring productivity: don't worry if you don't know your exact hourly rate. When you don't know the hourly rate for this first calculation, merely estimate the number of hours actually worked by you or your employees. Later, you will have more accurate figures for the subsequent calculations.

If you repair TV sets and make home calls, your service--call rate usually is about the same as your hourly rate, so use that figure at first. Also, estimate your own productive time, or subtract the hours not devoted to repairs. The hours you spend buying, managing, accounting, selling, etc., really must be considered part of the overhead, and should not count toward the productive time.

Here is the productivity formula: Labor produced divided by hours worked divided by the shop hourly rate equals productivity.

Let's assume the total labor produced last week by one technician was $500, the number of hours worked was 40, and the shop's hourly rate was $25. When we plug them into the productivity formula, it reads this way: $500 divided by 40 (equals 12.5) divided by $25 equals 0.5 (or 50%). Note: An alternate way of handling the math is to multiply the hourly rate by the number of hours worked per week. That represents 100% productivity. So, $25 times 40 hours equals $1,000, which is the minimum possible to produce. Then divide that figure by $500, the actual income, to give the productivity ($500 divided by $1,000 equals 0.5, or 50%). Your productivity is figured the same way, except you take only those hours actually used for repairs (those hours when you wore the manager's hat don't count here).

----------------

TABLE 3--Total Shop Productivity

Formula: Annual total labor sales

Annual tech hours ÷ Shop rate per hour = ANNUAL PRODUCTIVITY

Problem: $75,000 - 6500 hrs. - $25 = ANNUAL PRODUCTIVITY

Step #1: $75,000 - 6500 = $11.54 per hour

Step #2: $11.54 - $25 = 46% Annual Productivity

---------------

Questions

What do you do about the time spent sweeping floors or cleaning the "john"; or the tech's time when he sells products at the counter? You should subtract the time a technician spends selling. That's a sales expense, not a service expense, and must be accounted for in the sales figures. The other chores that technicians often do (talking to customers, repairing trade-in merchandise, or delivering new sets) are necessary, and have value, which must be allowed for in the productivity.

In the larger shops, a bench tech should spend all of his time working as a technician, and an outside tech should devote 100% of the work day making service calls.

The manager usually does the non productive (but necessary) extra functions. This specialization is the main reason larger shops consistently show higher productivity percentages than those of the one-man to three-man shops. A larger percentage of the tech's time is used for direct production.

But, regardless of the shop size, 100% productivity is very rare.

What Is Good Productivity?

In many actual examples, the productivity varies according to the number of technicians (see Table 1). Productivity runs from 30% to 60%, with the larger shops showing the higher figures.

Those figures imply that a one man service department never can be as productive as one tech in a multi-tech shop can. On the surface, this conclusion seems to be illogical. If you calculate only the actual servicing time, the technician should be equally productive, regardless of the shop size.

Here are some of the factors that modify the results. The one-man operator usually works on all brands. Therefore, he can't become well acquainted with them all, and thus he works more slowly. The same problem occurs in finding parts. Perhaps he can't afford service data for all brands and models, and so it requires more hours to identify defective parts and obtain correct replacements. He is interrupted more often, and finds it difficult to get "back on the track" after each interruption. Lastly, he has no fellow technicians to give hints or advice. All of these impediments reduce the productivity of the small shop.

Efficiency equals more profit?

Unquestionably, larger shops have a higher percentage of production. However, higher productivity does not necessarily bring an equally large profit.

Larger shops usually have additional "backup" personnel, such as parts men, counter attendants, bookkeepers, receptionists, service managers, etc. These extra people remove the time-wasting chores from the technicians, thus allowing them to be more productive. On the other hand, the increased money from the higher production is needed to pay the salaries of these non-productive employees.

Of course, the costs of these "overhead" people are not part of the "direct labor" on the Profit and-Loss (P&L) sheet, because they are rated as clerical, management, or miscellaneous employees.

This is a gray area that is handled in many different ways by bookkeepers, so we'll give one more example to clarify the situation.

Apprentice

An apprentice certainly is not "overhead." His working hours and the income produced do affect the productivity--both his own, and that of the shop as a whole. If he has low productivity, his percentage will reduce the average productivity of the entire shop. On the other hand, he might be assisting the journeymen techs, thus improving their percentages. In that case, the apprentice would not be lowering the shop's productivity. His wages never should be considered as over head.

Table 2 shows the productivity of a typical (but efficient) shop.

Annual Productivity

Many technicians show very high productivity for a week or so.

However, such things as vacations, training courses, sick days, etc. pull down the percentage over a full year. Therefore, it is advisable to calculate the shop's total annual production. The method is the same, except that changes of personnel (two techs for part of the year, and four for the winter season) make it a bit dated.

One big advantage is that the averaging over a longer time produces a more dependable figure to use when setting prices, or when judging the improvement of the business.

Calculate the annual productivity by taking the total labor sales (without parts sales) from your P&L sheet. From the payroll records, obtain the number of technician hours worked (including your estimate of the number of service hours you contributed). Divide the total labor income by the tech hours worked. This is the annual income-per-hour. Divide the annual income-per-hour by the hourly rate of your shop, and the answer, expressed as a percentage, is the total annual productivity.

One example is shown in Table 3.

Comments

You should do these simple calculations of productivity for each of the technicians, including your self.

Successful shops keep a running weekly record of productivity, just as they keep a record of sales and expenses.

If your shop seems to have a problem because of low productivity, check for these causes:

• The paperwork is excessive; eliminate all you can, even just one function;

• Parts and supplies are not convenient for the techs to obtain, thus wasting their time;

• You accept repair jobs for the older products, which often have multiple and time-consuming troubles to slow down the techs;

• Your test equipment is old or inefficient;

• Tools are so scarce that several techs must share the same ones;

• Warranty repair jobs are not paying expenses; and

• Your service data and replacement-parts stock are not adequate.

Another advantage of measuring productivity is that you automatically will begin thinking more about it; and the thinking will lead to remedial actions. These and similar improvements will become key factors in your $30,000-per-year Success Plan.

(adapted from: Electronic Servicing magazine, Feb. 1978)

Next: Service Management Seminar, Part 3

Prev: