Dick Glass, former Executive Secretary NESDA, operates his own consulting firm.

Write to him at:

Dick Glass and Associates, 7046 Doris Drive, Indianapolis, Indiana 46226.

Phone: 317-241-7783.

Guessing about how much to charge for service can cause endless worry and problems. Methods are discussed for determining service rates that are profitable to you and fair to your customers.

Pricing Problems

Few service dealers know their actual costs of service calls, bench repairs, and other types of technical work. In fact, many shop owners, who calculated their costs, have discovered to their dismay that they are operating "below cost," Of course, no business can continue very long when its prices are lower than the costs. So, one of the first thoughts which occurs to a shop owner, after the figures prove his business has been operating below cost, is that the figures or the method must be wrong. After all, the business continues to operate.

Does this prove a mistake has been made? No, the answer is that the losses must be made up elsewhere..

Operating below cost

Here are several ways for a business to continue supply service work at prices below cost:

(A) Some shop owners rely on profits from product sales (TV receivers, tubes, and accessories, for example) to compensate for losses from low service rates.

(B) Many, especially those with one-man operations, work extra long hours for labor income that's comparable to others who work only 40 hours a week.

(C) Service shops limping along with below-cost prices often don't provide funds for retirement, vacations, sick pay, or insurance. Most businesses provide these for both owner and employees, and such fringe benefits can add 10% or more to the real income.

(D) The owner of a small shop might have his wife act as business manager and office girl, but not pay her enough (or anything) for her important help.

False reasoning

Why do shop owners continued to price their services below cost? Here are some of the reasons:

Their prices are comparable to other service shops in the area.

They assume, therefore, that if the others can make a profit at those low rates, then they too should be able to have a profit. (Actually, all of the servicers in the area might be operating below cost.)

They assume their bargain rates will induce the customers to like them, and perhaps buy some new products from them, thus making a profit.

They privately believe their technical ability must be low; therefore, it's best to reduce the labor rate.

Probably they downgrade them selves because of the many "tough dogs" that require many hours to solve. Perhaps they believe. "After all, I can't charge the customer the full rate for repairs that take many, many hours."

They are afraid their customers won't pay any more than the present rate. In fact, some gripe now about "exorbitant" prices, ever those that actually are below costs.

Everyone has heard these reasons (excuses), and they sound plausible.

But are they valid?

One example

Recently I visited a service-only shop whose regular charge for a TV service call is $15.00. Yet, less than a two-hour drive away are other shops regularly charging twice that rate. These other shops are just as busy.

Here are some conclusions to be made about $15 service calls:

An average service call takes one hour (including travel), so the shop never can receive more than $15 per hour of income.

If the productivity is 50% (high for most one-man operations), his per-hour rate can average only $7.50.

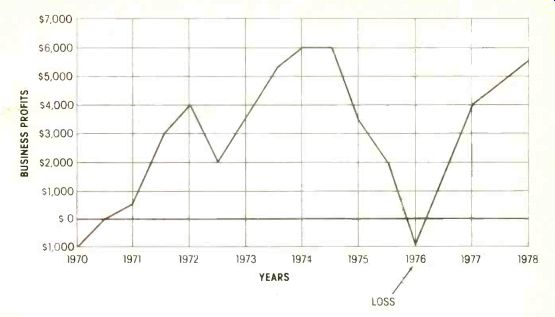

Figure 1 All businesses have variable profits (or losses-see 1976),

and a "business profit" fund should be set aside to fill in

during low-profit times.

Table 1. Per-Hour Labor Charge Calculation

One-Man Shop. This is the method for calculating the labor income you

need per hour in a one-man shop. All expenses (wages, overhead, ROI,

and business profit) are reduced to the cost for one hour (out of 40

per week or 2080 per year) and added. This is the income per hour you

need, if you could be 100% efficient. Since that is impossible, you

must multiply by your productivity percentage (in decimal form), to

obtain the income needed from each hour of chargeable labor.

Even if the shop had no overhead costs (rent, heat, telephone, etc.), and didn't expect any business profit or return on the investment, this technician/owner could not make more than $7.50 per hour.

Yet, many techs who work for someone else make that much, without investment or worry.

With ordinary overhead costs, this shop would find great difficulty in paying its owner as much as $5.00 per hour. At that rate for 40 hours per week, he could make only about $10,400 per year. And, the financial problem is compounded, if his wife-or a hired assistant takes care of the office while he's out on calls. This requires him to make several more dollars per hour to pay the helper.

Profit from parts sales can help subsidize the below-cost labor rates, but one man rarely can sell more than $10,000 in parts in a year. If he were to clear 50% for parts sales, it would bring only $5,000 more in gross profit.

How much should a technician employee make? The salary or "draw" of the technician who brings in the labor income is a large factor in deter mining service rates and profits. Therefore, the question of salary is very important in the present industry situation.

Today, technicians often are being hired at $8.00 per hour ($16,640 per year), with service managers receiving more. And it's still unusual for a shop-owner/technician to realize more than $25,000 per year. But even these insufficient rates are better than those of the past when techs were at the bottom of the economic order.

Compare those rates to a journeyman union electrician who makes more than $10 per hour plus benefits ($20,000 per year) almost anywhere. An IBM typewriter repairman does almost as well.

Electronic technicians must have far more training, knowledge, and experience than any repairman or electrician. In fact, their training never ceases. So, it seems that a technician should command a higher salary than those of lesser skills. The question is not, "Should techs make $25,000 per year?" Rather it is, "How can a tech make $25,000 each year?" Many people end a discussion like this one by saying, "Customers just won't pay that much." If you believe that-as many impoverished service dealers and techs do-you are exactly where the customers want you to be. You're trapped! And, it's useless to dream that you later will make mare money if competition eases, or you sell more products, or you become faster at making repairs.

A Better Solution

No, there is a better plan that will bring you more income now. The plan involves calculating your costs, setting some profit goals, and getting rid of your fears.

Perhaps, you now are thinking, "Sure it's easy for Glass or some one not in my position to say that.

But, I can't take the risk of losing the business it's taken years to build up." The good news is that servicers who established realistic service rates didn't take any risks at all.

Invariably, they found their fears to be unfounded, and they wished they had taken the step before.

Also, there are no known cases of realistic pricing causing the failure of a service shop. There are hundreds of businesses which failed from too-low prices.

Get started

After you have set some profit goals according to our previous advice, now is the decisive time to review your service rates. Find out what your rates should be. Of course, no one will force you to raise your rates. But you owe it to yourself to determine what they SHOULD be.

If you examine your costs and then realize your charges are too low, you don't have to raise them in one large jump. Instead, you can change them a step at a time. For now, you need to understand HOW to set your rates. It's much easier to justify your higher rates-both to yourself and to your customers after you know that the method and the pricing results are valid and correct.

The Ingredients of Your Charges

These costs must be included in your prices:

1. technician's wages;

2. overhead expense;

3. return on investment;

4. business profit; and

5. the productivity factor.

Each of these will be discussed in detail.

Technician's wages You must pay a technician to produce service income. It makes no difference whether the tech is you or an employee. One or both have to do the work, or no income is produced. Your shop's costs can't be calculated without including an "equivalent" technician wage for those hours you spend doing repair work. Some shop owners fool themselves by not including the cost of their own direct labor production. Of course, if you are an absentee owner, your compensation should not be included with the direct labor. But most shop owners are technicians, and they should receive at least $8 per hour for their repair time.

Overhead

Don't include technician wages or parts costs in "overhead" expense totals. Overhead is the operating expenses your business must pay, such as rent, utilities, truck expenses, insurance, advertising, and so forth. Service-only shops commonly have overhead totaling 40% of income. Some have over head as high as 50%.

Many bookkeepers don't list the owner/manager salary properly, thus disguising either the true overhead cost, or the true direct-labor cost (or both). If you are not sure how this should be handled on your books, refer to Part 3 in the March issue of Electronic Servicing.

Return of Investment

Few shop owners ever think about or calculate the amount of money they have invested in the business. But, if you borrowed $10,000 to buy parts or test equipment, you surely would pay about 10% ($1,000) annual interest for the use of that money. In the same way, if you "loan" your business $10,000 of your personal money, you certainly deserve the same amount of interest. This is "return on investment." You're just cheating yourself if you invest your money and don't expect interest.

Inflation alone will decrease your investment by 6% to 10% per year, so a modest 6% or 8% return-on-investment merely keeps up with inflation, without permitting any interest.

You MUST calculate the "cost-of-money" and include it as a factor when you set realistic service rates.

Business profit "Business profit" is not the same as money made by the business, and which goes into your pocket.

No business ever operates at constant levels (see Figure 1), but has ups and downs. Therefore, you must hold in reserve some business profits to pay the bills during low periods. Otherwise, you are forced to borrow, or take money from your personal bank account. Even if your plan calls for a business profit of only 5% of total sales, you must include this in your costs and in your prices.

Productivity

Productivity really isn't a direct factor in your costs. But after you settle on the per-hour income that you must have for each hour your doors are open, your per-hour income MUST be divided by your productivity percentage (as a decimal) to establish your actual service rate. It's not enough to calculate what you need per hour and "hoping" you will get it. Think of the many hours of "lost" time (answering the phone, talking to customers, etc.). Everyone from farmers to General Motors includes lost time in the price of the products, and so must you.

Table 1 first shows how to calculate the per-hour income needed when the productivity is 100%. Then, that figure is divided by the actual productivity as a decimal to show the rate for each chargeable hour.

Is your shop 75% productive, rather than 50%? That's good, and the increase poses no problem. In Table 1, divide $14.01 by .75 instead of by .50. This gives $18.68 as your per-hour service rate, instead of $28.02.

The calculation shows how productivity affects your rates. In the past, few servicers included it in the charges. Probably this error ac counted for most cases of poor service income.

Including the productivity percentage becomes even more important when you learn that many shops average only 30% to 40% productivity. Change the productivity percentage in Table 2 to 30%, and you would have to charge $46.70 for each productive hour to average $14.01 for the 40 hours of each week.

Or, looking at the problem from another angle, a shop charging $15 per hour at 30% efficiency could bring in only $180 in 40 hours, or about $4.50 per hour! Sometimes this happens to new shops.

Two-Man Operation Now that you know the basic ingredients of your per-hour charges, let's examine the differences between the one-man shop (Table 1) and a two-man shop (Table 2).

Notice that the overhead and the total investment both increased by 40% because of the additional technician. However, the increased volume of business allowed a per-man reduction of the return-on-investment (ROI), the overhead, and the business profit.

Also, the second technician receives only $7 per hour, compared to $8 for the owner. (In a partner ship, both probably would receive $8 per hour, or whatever rate was agreed on.) For practice, you should make the calculation of Table 2, but changing the wages to $5 and $4, Service Management continued from page 35 with a 40% productivity. The per-hour rate will be given at the end of this article.

After you have become proficient with the method, calculate the rates for your own shop, using the actual costs of wages and overhead. Include the return-on-investment you want, based on your actual investment. If you don't know your investment, figure it now. Add a business profit that you think is reasonable to cover the low periods.

All of these items together make up the amount you would receive for each hour of labor, if your productivity were 100%. Because 100% productivity is impossible, you then divide that figure by your productivity percentage (expressed as a decimal) to arrive at the hourly rate you MUST charge, if you are to reach your goal.

Flat-Rate Pricing

Many shops use flat-rate pricing rather than hourly rates. That practice does not conflict with the principles given here. After all, these "flat rates" are based on some hourly figure determined by you. If you charge $20 for service calls and $40 for bench major repairs, you are working on a $20 per-hour rate.

So, if you prefer flat rates, determine your needed hourly rate and set the flat-rate prices for this rate versus the amount of time you estimate (or obtain from a time study) each particular job will require.

Sperry and Tech Spray pricing

Two different pricing systems are available to servicers who want to price repairs by the hours worked.

The Tech Spray and Sperry Tech systems both work well for applying your hourly rates to the work functions.

Either system can be converted to flat rate. However, I don't recommend flat rates. Most servicers who solved both complaints and profit problems believe that an "increment" system based on a definite hourly rate is best.

Comments

Of course, you understand that the amounts used in Table 2 are only for an example, and your figures are expected to be different. You should expect more than 10% return-on-investment. If I were doing it, I would try for a larger business profit than the example of 5%. And of course, if both techs are experienced journeyman-level craftsmen, they should be receiving more than $7 to $8. Only you can determine these figures, and include them in your rates.

Some shop operators will feel the amounts in Table 2 are too low; others probably will believe they are too high. Two conditions can reduce the hourly rate: (1) The techs could work longer hours. In a partnership, the owners could agree to not accept overtime pay. (2) Parts profits could be included.

(Many managers insist parts profits should not be a factor in labor rates.) In this example, profits from combined parts sales of $10,000 a year could be used to reduce the labor rate by $2.40 per hour. It's your decision whether or not to make these concessions.

Practice calculation

For the practice calculation of the two-man shop labor rate, you should have an answer of $22.06 per hour per man.

Next Month

The "building-block" (or Nesvik) system described in this article is a good method that's sufficient for you to establish new rates or rework old ones. And I strongly urge you to make the calculations and evaluate the results.

However, there is another system (I will describe next month) that has some advantages.

Regardless of the method you use for determining your labor pricing, you should understand it thoroughly, know why every item is necessary, and believe in the rate. When you know the price rate is fair to both you and your customers, you will win every discussion about prices! Remember, to reach that goal of $30,000 (or whatever amount you chose), you should not depend on good luck to solve your problems, but you must plan wisely and work with single-minded purpose. One vital step is calculating your proper service rates.

Table

2. Per-Hour Labor Charge

Calculation Two-Man Shop . The method of calculating the per-hour labor

income of a two-man shop is similar to that in Table 1, except the first

figure is the income needed for both men, if they were 100% efficient.

This figure should be divided by 2, giving the per-hour 100% labor income

for each technician. Then, it is multiplied by the productivity percentage

(in decimal form) to show the per-hour chargeable labor of each man.

(adapted from: Electronic Servicing magazine, May. 1978)

Next: Service Management Seminar, Part 6

Prev: