By Dick Glass, CET

Increasing profits from parts

When your component parts profits are insufficient, probably you should determine your own retail prices, rather than using "suggested list" prices from the manufacturers.

Parts pricing problems

"How can I price parts properly and profitably?" This question has been asked of me many times in my work as financial advisor and business consultant to independent sales and service stores.

In addition, most shops are having increasing difficulties in maintaining an adequate variety of the parts. Sometimes the excessive time required to locate and deliver a certain part can cancel all of the profit on the sale and even reduce the labor profit. Although the problems of parts availability are not a direct factor in the pricing of parts, the two problems do affect each other. Therefore, we will deal with both together.

Here are some of the current parts problems:

• Sales of high-mark-up vacuum tubes are diminishing.

• Electronic products are becoming more reliable, requiring fewer re pairs.

• Fewer parts are used per repair, than in previous years.

• Repairs of each brand require many more specialized parts, and fewer universal parts. Thus, the stocking problem is made worse.

• Although the "suggested" mark up of some parts remains profitable, more and more large components--such as modules, picture tubes and special items--have list prices that allow as little as 20% gross profit.

• Parts gross-profit percentages are steadily diminishing, according to profit-and-loss statements.

• Stock parts become obsolete at a faster rate, yet a wider variety of parts are needed to minimize extra trips to the local distributor.

• Many dealers believe they must follow all "suggested" list prices.

• Few know that it's legal to establish their own selling prices.

Parts versus labor profits

In the "good old days," profit from parts sales provided most of the income in a high-percentage of electronic-repair shops. Labor was billed at less than cost.

This was possible because picture tubes failed more often, and small tubes carried enormous mark-ups (in addition to having a very high rate of replacement). By contrast, the failure rate of modern solid-state color TVs has plummeted to about one repair in two or three years -and the rate continues to drop. Also, the volume of parts sales is diminishing even more rapidly.

Under today's conditions, then, it's not possible for an electronic-repair shop to operate solely from parts sales. And, if you are trying to subsidize inadequate labor rates by using parts profits, your business is (or shortly will be) in deep trouble!

Operate without parts profit

What should you do, if you are depending too much on parts profits?

Well, the answer is in two halves.

First, imagine that you have zero parts sales. Figure your labor expense versus needed income, and calculate a labor rate that will bring in sufficient money to pay your employees properly and to reimburse yourself for your time, investment and risk. Begin using the new labor rates.

Second, after new labor rates (which need no subsidy) are established, you should calculate the mark-up required for you to make a normal profit from the sales of component parts.

Remember to include all of the legitimate expenses that often are ignored and left in the miscellaneous category.

After you have instituted separate rates and profits for labor and components, your business will be secure, even if parts sales drop to zero.

Remember, this major decline of parts sales and profits probably is not due to any mistakes on your part, but it's a general change in the entire industry. This conclusion is verified by careful studies of the following "typical" profit-and-loss statements.

Analyzing P&Ls

Figure 1 and Figure 2 are slightly-exaggerated examples of profit-and-loss statements for the years of 1970 and 1978.

Notice that both labor sales and labor costs increased (probably from inflation), although the percentage of profit declined.

Parts figures, however, changed the most. Not only did the parts sales decline from $40,000 to $20,000, but the costs rose to 75% from the former 50%. Parts profits in 1970 probably were helped by sales of receiving tubes. But inflation should have increased the 1978 parts sales almost to the 1970 level. Therefore, the drop of parts sales in 1978 is highly significant.

These trends are impossible to spot on a monthly basis, because of seasonal variations. Yearly P&Ls might show bad conditions, but a comparison of many yearly P&Ls certainly will pinpoint the problem area.

The problem

According to the P&Ls of Figures 1 and 2, the basic problem is a loss of $15,000 in parts gross profit. $10,000 of this loss could have been avoided if the parts had been priced for a flat 50% profit.

Also, don't overlook the additional indirect expenses for time spent locating the exact-replacement components demanded by solid-state designs.

Some owner/managers believe that the general change from universal parts to specialized parts was one of the major causes of increased overhead and reduced profits.

Solve the problem

Before you attempt to solve the parts-profit problem, analyze your labor rates. Attempt to increase productivity, and then raise the labor rates so the labor income is two to three times the cost of labor and fringe benefits (including taxes on wages) plus the owner's wages (when he functions as a technician). After the question of labor profits is settled, you can face the parts problem squarely, knowing that the realistic labor rates offers protection even if parts sales dwindle to zero. Don't depend on parts-sales profit to supply any insufficient labor income. Both must show a profit after expenses.

Simply stated, the missing parts profit can be restored by increasing the selling prices. Of course, we have been brain-washed for many years to accept manufacturers list prices, without any questions. The inference is that, if you operate your business right, these list prices will bring in a normal profit.

Therefore, you probably will need to re-orient your thinking by studying these truths:

• You are free--both legally and morally--to set your own parts selling prices, according to the profit you need.

• From your monthly P&Ls, figure the parts-cost percentages. If they average 80%, but you need 50%, then your selling prices are too low.

• Losses from obsolete parts should be counted as overall parts expenses.

Remember, you didn't stock the components for yourself, but for the customers' benefits.

• Added space required for the wider variety of specialized parts is expensive to you. Therefore, parts prices should be raised to include such expenses.

• Those extra trips to the distributor for special parts should not be absorbed as general expenses, but must be added to the parts prices.

• Include parts shipping charges in the selling prices. They are legitimate expenses.

Figure 3. This view of a Sperry Tech parts-pricing book shows the format

for the universal-parts listings and the locating tabs at the right.

Figure 4. Six tables of mark-ups and discounts are available. You choose

the mark-up you want (thus, making the pricing plan legal).

• Realize that parts prices are changing constantly. Although it is a nightmare to keep up with continual price changes, it must be done. (We will suggest an easier way, shortly.)

• A printed book or list containing all of the parts prices should be available to each employee. This is especially important, after you have decided to set your own prices.

After you study these reasons for establishing your own parts prices, you should be convinced the benefits will outweigh the work required to set up the system.

============

Facts about Sperry Tech parts placing

With the Sperry Tech Parts Pricing System, a computer stores the net prices of parts from 17 major TV and stereo manufacturers, plus universal parts, semiconductors, tubes, and a tax table. After a service dealer selects the mark-up he wants (there's a choice of 6, from 45% to 65% discount), the selling prices are calculated and printed by the computer, and the pages are inserted into a durable loose-leaf book, which has tabs at the edge to make the sections easy to find (Figure 3). All prices are on a sliding mark-up, with low-priced parts having the largest mark-up and expensive ones showing less.

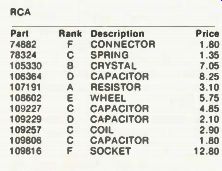

Figure 4 shows the Table Number 4 of mark-ups.

As shown in Figure 5, the specialized parts are listed by manufacturer's number, and the letters "A" through "F" tell the approximate turn-over. "A" parts are fast movers, while "F" parts usually should not be stocked.

Any number of books can be ordered. For example, two 6 inch x 9-inch books, plus a subscription to the Automatic Updating service, cost between $16 and $24.50 per book, depending on how many books are ordered.

The monthly subscription fee is paid though the Electronic Funds Transfer System (EFTS) and automatically deducted from the bank account of your company. For more information about prices or the books write direct to Soarry Tech. Although the prices seem high, the in creased profits from parts sales should make it a bargain.

Write to Sperry Tech at P.O. Box 5234, Lincoln, Nebraska, 68503, or call 402/464-9181. This information is not a paid ad, but is presented as a service to our readers.

============

Designing a parts-pricing system

Keeping up with parts price changes is not easy. You must acquire the latest price lists, including those for tubes and special parts. Then, you must figure new retail selling prices, based on the mark-up you need. Finally, these new prices must be typed or printed, and copies made for all your employees.

Sliding mark-ups

Audio shops were the first to be affected by the all-solid-state equipment, which requires low-margin, slow-turn, and fast-obsolescence replacement parts.

Managers of these audio shops learned rapidly to disregard the traditional manufacturer's suggested list prices.

Many of them adopted a sliding scale of price mark-ups. For example, parts that cost under 50 cents would retail for $2.50. Parts costing between $1 and $2 would sell for $5 to $7. Higher net cost items progressively received less mark-up, until those above $50 were sold for the manufacturer's list price.

The disadvantage of this method is that you must look up your cost of every individual part and then calculate the selling price. It's time consuming.

Figure 5. Here are a few listings from a page of specialized components,

showing the type of information and the layout.

The Sperry approach

Another practical method of pricing parts combines a sliding mark-up with the detailed and complete printed listings of parts, but has someone else with a computer make up the lists (for a moderate fee) and install the pages in an attractive book.

This company with a computer is Sperry Tech (the same one offering the pricing guide). John Sperry had the same pricing problems as all other shop owners and managers have. His solution now is offered to other shops.

Details are given somewhere in this article. Briefly, it is a complete system that supplies parts prices of 17 manufacturers.

It's legal for you to use such a system, because you choose the percentage of mark-up you want.

Obviously the system is handy to use. But there is another important benefit: a printed book of prices is an "outside authority" in the eyes of the customers.

Establish a parts-pricing system

Some shop managers estimate that following these parts prices (which are determined by the methods I have outlined) could increase the profits of a small repair shop by at least $50 per week.

Obviously, such a sizeable boost of income is worth investing considerable time and money to obtain. Therefore, I urge you to establish your own parts-pricing system-one that will bring you the mark-up necessary to stay in business and provide good service to your customers.

(adapted from: Electronic Servicing magazine, Nov. 1978)