By Dick Glass, CET

This is a reprint of Chapter 13 from the Service Shop Management Handbook, book number 21602 from Howard W. Sams & Co., Inc. The book sells for $9.95.

Most shops seem to feel that it is nearly impossible to closely estimate the hourly rate they need to make a reasonable profit and to pay wages and overhead. They say that there seems to be too many variables: the amount of service work seems to vary; the tough dogs require so much extra time; and the flat-rating of service calls, over-the-counter jobs, and bench-work makes an hourly rate of little value.

These things all seem to be true.

However, the flat-rate charges have to be based on actual average time spent. For instance, the charge for a TV bench repair should be about three times the charge for a service call because it takes about three times as long to do the average bench repair.

Tough dogs are a permanent part of your business

As long as you are in the servicing business, you will have tough dogs. Every one of the 190,000 American service technicians regularly runs into tough dogs, so it follows that tough dogs are not your fault and you should not feel that you must pay a personal penalty in time and dollars for them. You should estimate your tough dog expense and consider it the same as any other legitimate expense, as a cost to be included in your hourly rate.

The fact that there are so many variables in the servicing business is only one more reason why you should know your exact cost of doing business and know exactly what your hourly rate must be. If your rates are only based on how fast you think you can repair a set and you do not consider your lost time (billing time, parts procurement time, management time, and so on), you are like a landlord who rents out a house only six months out of the year, yet who bases the rent charge on its being occupied all 12 months of the year. The house eventually will fall into disrepair because the landlord can not afford to repair it, and since he is losing money, he has no incentive to repair it.

Some more reasons for knowing your hourly cost of doing business are:

1. Once you know your rate per hour, you can better estimate special jobs for which you have no established flat rate.

2. Many shops find that their service-call price matches their hourly rate. (Time studies show that an average service call involves about one hour of time.)

3. Pricing systems, such as the Sperry Tech TV & Radio Tech's Guide to Pricing or Tech Spray Pricing System, are workable only if you know your hourly rate.

4. Warranty work can be analyzed better if you know your cost.

5. Knowing your cost-not guessing-can give you the facts you need to counter customers' complaints regarding your prices. (You need the conviction that your prices are fair.)

6. Should you ever be the target of a "TV fraud expose" by consumer agencies or communications media people, you can easily defend yourself if you know your cost (especially if you are also acquainted with industry averages).

Two methods of establishing rates are discussed in this book.

They are the Nesvik System and the Sterling System.

The Nesvik System for calculating rates Using the Nesvik System, we will analyze the costs that a typical one-technician TV service shop might have and the profit and return on investment that it needs.

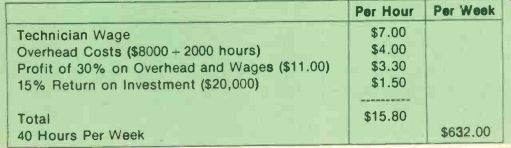

By adding all of the costs shown in table 13-1, we can establish an hourly rate.

Based on an hourly rate of $15.80 and a 40-hour work week, the technician owner must have $632 per week (see Table 13-1).

Since the technician cannot charge for all the 40 hours that he works each week, the $632 needed each week must be divided by the number of hours actually worked.

Let us assume that 25 hours per week is the actual time spent on service work. To determine the hourly rate, simply divide $632 b y 25 hours and you get $25.28 per hour.

If the technician owner were able to charge for an average of only 20 hours per week, or 50% of the 40 hours, then his rate would have to be $31.60 per hour (see Table 13-1).

If this typical dealer calculated the rates as we have in Table 13-1, he would seed $25.28 per hour and would have to be productive 621/2% of the time. If service is being performed on warranty or contract repairs, where no parts profits are realized, the $25.28-per-hour rate is a must. On repair work where parts are sold, parts profits can be used to decrease rates. For instances, if labor income was $25,000 and parts sales were $15,000 (at 100% mark up), this would give a gross profit of $32,500. He could then charge $6 less per hour and still make $632 per week. The hourly rate then would be $19.28.

-----------------------

Table 13-1. Using the Nesvik system for a one-technician television

service shop

Per Hour Per Week

Technician Wage $7.00

Overhead Costs ($8000 +2000 hours) $4.00

Profit of 30% on Overhead and Wages ($11.00) $3.30 15%

Return on Investment ($20,000) $1.50

Total

$15.80

40 Hours Per Week $632.00

---------------------------

Calculating rates in multiple-technician shops

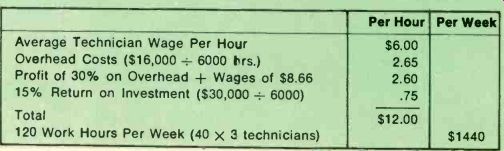

You can easily see how the hourly rate is arrived at for a one-technician shop (Table 13-1). It may become confusing when you try to use the same (NESVIK) system to calculate rates in multiple-technician shops. So let us attempt to calculate the rates as if we were operating a three-technician shop.

Wages-We can reach an aver age per-hour wage for the three technicians. Using the actual wages paid in the three-technician shop we will arrive at an average wage of $6 per hour.

Technician 1 earns $ 7 per hour Technician 2 earns $ 7 per hour Technician 3 earns $ 4 per hour Total $18 per hour Divide $18 by 3 technicians = $6 per hour.

Since the three technicians plan to each work 40 hours per week (taking two weeks vacation) we can use 2000 hours per year as their total annual work time, each, or 6000 hours combined work time for the three.

Technician 1 works 2000 hours Technician 2 works 2000 hours Technician 3 works 2000 hours Total 6000 hours to obtain 1 year's labor income.

Then, in the example of the three-technician shop we must have $12 income each hour of the 120 technician-work-hours. To deter mine the hourly rate to be charged for service work, we need to know the probable productivity of the three technicians. This we would find out from calculating previous months or the past year. If productivity turned out to be averaging 50%, then the $12 per-hour income needed would require a $24 per hour charge rate for service work.

Overhead--Note that the over head figure used in Table 13-2 is larger than that shown for the one-technician shop. A three-technician shop should have a larger overhead. Unfortunately, there is no "standard" overhead for any size of service shop due to the lack of conformity in this business. Some one-technician shops have overhead expenses as high as 40% or 50% of total sales. Others, working out of low rent locations (homes, garages, etc.), may incur overhead expenses as low as 20%. Some shops do a major amount of their work in the home thus incurring heavy truck expenses while others do very little outside work, thus incurring small vehicle expenses. Overhead expenses are not predictable for service shops as any industry. They are, however, predictable enough for the individual shop to compare with previous monthly or annual results. To compare overhead expense percentages with other similar shops you must first analyze both shops to make sure both overhead figures include similar items. For instance, one shop may include owner's salary in overhead expenses and this may be a sizable amount, perhaps 10% or more. The shop to be compared may neglect to ac count for any owner salary in either overhead or direct labor expenses.

This discrepancy would make comparison invalid unless these items were accounted for.

In the Table 13-2 example we have shown an increased overhead total of $16,000 ($8000 higher than the one-technician shop in the Table 13-1 example). The overhead, once it is known, should not be divided by the 2000 hours the shop is open for business, but should be divided by the 6000 hours in which the labor is produced (3 X 2000 hours).

Profit-In our example we are using 30% of overhead and wage costs as the goal for a business profit. You may not like using this method to arrive at a planned profit figure. Instead you may want to set a profit goal based on total sales. By doing so you can come up with the same profit goal ($15,600).

For instance, if you anticipated a $100,000 annual total sales amount and you set a goal of 15%-of-sales as the profit goal, you would have reached the same approximate total and per-hour amount even though you used a different formula to arrive at that amount. In this example we use a profit percentage of the two cost items-wages and overhead expenses. By using this method you can estimate the profit a beginning business needs. That is not to say this means of establishing a profit goal amount is better than the total-sales method or any other method. In fact, once you get used to ratios, you may want to establish your profit goal using a percent of assets, or a percent of total investment, rather than the method we use in the Nesvik system, or the total sales percent method.

Return On Investment--The 15% return on investment used in the previous example may be too low.

Remember that the return on investment should be thought of as an amount of profit or income, in addition to the business profit, or the wages you may personally receive. Some business people expect to receive their total investment back within five years. If that were the case, a 20% return on investment would be required $1 per work-hour instead of the 75 cents we used in Table 13-2). Note that the return on investment amount is also divided by the 6000 hours worked, not the 2000 hours the business is open.

Productivity---Once you have made the calculation and arrived at a per-hour income figure that is necessary to produce the dollars your business must have, the very real effect of lost time must be considered. As in the Table 13-1 example you can see that the $15.80 per-hour income figure must be divided by the productivity percentage of the shop to arrive at the amount the shop must charge in order to average $15.80.

If all service repair jobs were the same and each job took the same amount of time; there was a constant supply of repair jobs; there were no recalls; there was no time lost searching for parts and schematics or talking to customers about estimates and so forth, the above shop could have a "charge rate" per-hour of $15.80. This would bring in the necessary amount of income. But there is a lot of lost time in the repair business. In fact, small shops rarely manage to achieve even 40% productivity. Something continually wastes the available time. Rather than hoping that in the future productivity will increase, you should face the truth as it is now. If your productivity is 30%, decide either to improve it, or use that 30% figure in establishing your per-hour rate. Otherwise you are fooling yourself.

If the shop in Table 13-1 had a percentage for productivity of 30%, what would the hourly charge rate be to maintain the $15.80 hourly income requirement? It would be $52.67! To charge less than $52.67 (with actual productivity of 30% in that shop) means something has to be reduced. Since overhead, expenses cannot be reduced, one of the other three items will have to be eliminated. In practice, the shop owner would hope for improved productivity. That will not occur, so the business profit will be eliminated as well as the return on investment. With those two items out of the way, the overhead and wages are only $11 per hour, which translates into a $36 hourly charge rate. Only a few shops have the courage to charge that amount right now though, so unless the shop has some product sales or parts profits to fall back on, the owner will probably reluctantly accept wages of less than the $7 per hour goal for his time. If he is willing to accept only $4 per hour for his time, he can get away with charging only $27 per hour or even less if he subsidizes the labor with parts profits (as many do for some reason).

-------------------

Table 13-2. Nesvik system used for a three-technician shop

Per Hour Per Week

Average Technician Wage Per Hoar

Overhead Costs ($16,000 = 6000 hrs.) Profit of 30% on Overhead + Wages of $8.66

15% Return on Investment ($30,0)0 = 6000)

Total 120 Work Hours Per Week (40 x 3 technicians)

$6.00 2.65 2.60

.75

$1440

$12.00

-----------------------

You may find in your shop that your own productivity is pretty low and that your charge rate, three fore, must be high as in the previous example-$52.67 per hour.

You then may say, "Gosh! There is no way to charge $52.67 per hour, in this business." That may be true. The secret is, however, to see what you should be charging and then worry about whether you can get it. If you never know what you should charge you cannot possibly improve on your present position. Your only solution to low profits is to work harder and faster and to hope. You will hope that recalls will disappear, that time-wasting customers and sales people will leave you alone, that difficult repairs will diminish, and that your employees will become more efficient. That will not hap pen. The real result will always be a low income for you.

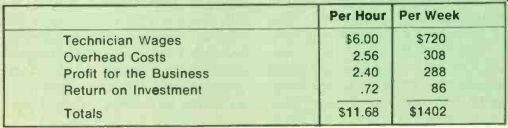

Nesvik calculation on a weekly basis

To figure your rates on a weekly basis is more difficult, because your overhead expenses may be hard to average out, since they vary so much from week to week, and even from month to month. However, for purposes of showing you how to figure your rates, simplified examples of a three-technician shop are as follows:

Wages---The average hourly wage for a three-technician shop can be found by adding their wages together and dividing the total by three.

Overhead---It is best to take the overhead figure for last year (from your tax form or your annual profit and loss statement) and divide it by 52 (weeks) to find the average weekly overhead, then $16,000 ÷ 52= $308 per week.

Profit---If you set your annual profit goal at $15,000 (in addition to your wages), then $15,000 ÷ 52 = $288 per week.

Return on Investment---If your investment total is $30,000 (as an example) and you expect a 15% return on that amount of money, then $30,000 x 0.15 = $4500 per year, and $4500 ÷ 52 = $86 per week.

Performing the calculations (Tab le 13-3) on a weekly basis produces a $11.68 per-hour "income" amount rather than the $12 amount reached in Table 13-2. The reason for the small difference is that we have not considered the two weeks (each) vacation time as we did in Table 13-2. (Without considering vacations the 40 hour weeks would allow 2080 hours of work annually, instead of 2000.) The horror of facing the truth If your present rates are $15 per hour (or thereabouts) it may be difficult to accept the fact that you may need twice that amount to be profitable. The important thing is to face the truth and to at least understand what your charges must be. If you feel that competition, or past precedent, or your future customer relations will suffer if you start charging realistic rates, you can continue to maintain your rates at their present levels. If you, as a manager, do know what they should be, and you know the amounts were arrived at scientifically, you may eventually want to do something about narrowing the gap between present rates and those you must have to be profitable. If you can solve the problem by improving productivity that is fine. For in stance, in the above example, the $11.68 per-hour rate needed is only a $12.98 per hour charge rate at 90% productivity for all three technicians. Unfortunately, 90% productivity is unattainable in most shops and 20% to 40% is the rule.

Since most shops do not know that, and have never figured productivity in their shop on a weekly or annual basis, they assume it should be 80% or 90% and go about setting their rates accordingly. It's like putting your money in a pocket with a hole in it that you are unaware of, never realizing why you cannot fill your pocket up.

Another important feature of the Nesvik system is that it allows you to take each of the five factors--wages, overhead expenses, ROI, profit, productivity--into account.

By understanding the effect of each actor, and the (fair) amount of ach, it is easy for you to justify your charges whether it be to the customer, licensing board, manufacture, or government agency who may not think that your prices are air. With the absolute knowledge hat they are proper you will always have the upper hand in any pricing dispute.

----------- Table 13-3. Nesvik system showing the hourly income requirement

and weekly amount needed

Technician Wages Overhead Costs Profit for the Business Return on Investment Totals

-----------

Quiz

Answer the following questions either T (true or F (false).

1. The Nesvik system of figuring service rates produces an hourly income requirement that can be used to set the hourly rate at which repair work should be charged.

2. The Nesvik system can be used to establish or adjust "flat-rate" prices also.

3. Assuming that maximum merchandise and parts profits are already being realized, the alternatives to low income in a service shop are increase prices or increase productivity.

4. A shop owner discovers that the shop needs $20.00 per hour, each of the 40 hours per week it is open for business. The owner calculated the technicians' aver age productivity and found it to be 35%. The per-hour "charge rate" must be set at approximately $57.00.

5. A manufacturer with whom you might enter into a servicing contract agreement, or a government regulatory agency would probably disallow any consideration of investment return or business profit, should you use these two items in explaining why your proper service rates are justified.

6. Productivity of 30% probably shows a lack of management ability and should not be tolerated or used as an excuse for higher service charges.

Quiz answers

1. True. The system separates the four real, distinct costs that make up the hourly minimum income that service businesses must have to succeed. By separating each of the four ingredients of the hourly rate, a realistic judgment can be made as to the proper amount of income that will be required t.) satisfy each one. Added together, the total hourly income requirement can easily be under stood or explained.

2. True. Flat-rate prices (which most shops still use) are always established by dealers in varying amounts, based on the anticipated (or experienced) times each type of repair appears to take. Figuring out the needed hourly income rate is useful even in "flat-rate" pricing shops as, once the hourly income rate is determined, the flat rates can be adjusted to produce the required amount.

3. True. Most unsuccessful shop owners hope something else will COME along to substitute for inadequate service charges. Many expect the repair jobs to eventually get easier. Some hope the future will hand them a new and unique sales product that can provide profits with which to subsidize unprofitable service rates. Since there is no reason to expect such improvements, the logical answer then is to establish realistic and profitable charges, in addition to attempting to increase productivity.

4. True. It could be less if the shop could figure out a way to improve on the 35'4 productivity average of the technicians. It is extremely difficult for a small shop to overcome it, however. If the shop owner is looking the facts squarely in the eye he can see he must charge for repair work at near $57.00 per hour. If he has healthy parts profits the $57.00 rate could be reduced somewhat; however, parts profits are not the major portion of service income as they once were, which may make the reduction that could be made rather small.

5. False. Practically all of these "big business, big government" people are totally ignorant of costs of doing service business. If you know your costs and can explain or justify them as the Nesvik system allows you to do, you will, in the majority of cases, convince others that you know what you are doing and that your prices are fair.

6. False. The extreme difficulty involved in electronic repairs, the difficulty in obtaining literature and parts, the unserviceable products, and dozens of other problems with repair work make 30% productivity more the rule than the exception. To average 30% while setting service rates expecting 60% is to blind oneself to the truth.

Also see: