by David Hamilton

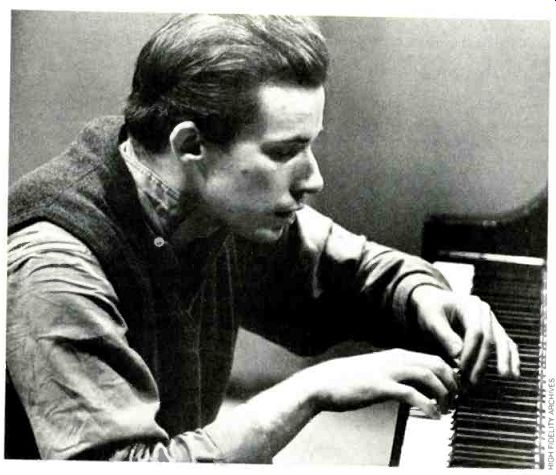

GLENN GOULD was an extraordinary pianist, at the height of his powers, and he will of course be missed for that reason alone; we can never have enough such performers.

But he was something rarer as well, a musician who took nothing for granted, from the fundamentals of piano technique and sound, through the generally accepted concepts of style and interpretation, to the whole idea of performing public concerts.

One doesn't have to have agreed with Gould's conclusions about any of these matters to recognize the value of the questions he asked, and to regret deeply that he is no longer around to ask further questions.

Let me call attention here to but one aspect of Gould's uniqueness. In an historically-minded age, he remained an old fashioned non-historical performer--and not merely in his insistence on playing Bach on the piano. Every aspect of his playing tempos, phrasings, dynamics, textural conceptions, and, of course, expressive character--grew principally from Gould's own inner resources, from his acute if highly personal perceptions about each individual work and from his very decided musical sympathies and antipathies. In his youth he had been fascinated by Artur Schnabel's "way of looking almost directly at the music and bypassing the instrument .. . He didn't seem to care about anything but the structural concept behind the music." Gould's playing (especially of Beethoven!) was nothing like Schnabel's, but he clearly aspired to a similarly penetrating vision of musical structure.

Like Schnabel, Gould was a child of his time-which may seem a truism until you reflect upon how many pianists of his generation have their roots somewhere like a century ago. Schnabel belonged to a musical tradition strongly influenced by Brahms and Schoenberg, and his playing responded to the same aspects of music that those composers thought crucial. Schoenberg played a major role in Gould's back ground as well, but his ideals of sound and texture clearly owe more to the neoclassicism of Hindemith (whom he admired) and even Stravinsky (whom he did not) than to the Brahmsian complexity of Schoenberg.

Another model, I fancy, was the playing of Wanda Landowska-not that he tried in any way to imitate the harpsichord, but rather that he was inspired by it to seek an equivalent contrapuntal clarity on the piano. Having achieved that--and how!--he had little truck with those aspects of harpsichord style derivative of that instrument's articulative peculiarities (e.g., the extensive agogic accenting so subtly exploited by players such as Gustav Leonhardt). Equally unhistorical is the brilliantly successful attempt, in his last recording of the Goldberg Variations, to achieve a kind of continuity of overall movement and tempo that Bach almost certainly never dreamed of; this is an achievement of intellect, technique, and perception that must enormously deepen our profound sense of loss at his passing.

-HF

----------------

What the Recording Process Means to Me by Glenn Gould

This item, previously unpublished and kindly furnished to us by CBS Masterworks, formed the script for a segment of a Masterworks in-house video project. Gould was asked to address the question "What does the process of recording mean to you?" Our "fee" for this article took the form of a contribution to the Glenn Gould Memorial Scholarship Fund at the University of Toronto. Readers who would like to make similar contributions may do so through: The Dean. Faculty of Music-, University, of Toronto. Toronto, Ontario, Canada MSS 1A1.

-Ed.

-------------------

I THINK THAT THE FINEST compliment one can pay to a recording is to acknowledge that it was made in such a way as to erase all signs, all traces, of its making and its maker. Correction: Its makers; as we all know, recording is a collaborative enterprise. The whole, long, complicated chain of events that begins in the studio when somebody presses a button and says. "Take one," and culminates when the master product leaves the pressing plant and makes its way into the world, justifies its existence and, indeed, its complexity only by the degree to which it can make itself-make all the ingenious technical feats that play their part in it-invisible.

Do you remember, back in the Sixties, that there was a ubiquitous buzzword called "process"? (As a matter of fact, I'm not sure that "buzzword" was a buzzword of the Sixties, but "process" certainly was.) Anyway, it became a very overworked term and a very abused concept, even though the excesses that were perpetrated in its name had their roots in a perfectly understandable pride of craft. Avant-garde filmmakers, for example. Deliberately--defiantly, even drew attention to the process of their work by disturbing its natural syntax, by challenging the expectations of the viewer, by saying, in effect. "You were expecting a reverse angle on this shot, were you? Sorry--no such luck, and oh, by the way, this is a film, is a film, is a film, so we have left the counter in at the head of the next reel: four, three, two, one. . . ." Well, you know the sort of thing I mean.

Of course, in all fairness, we in the record business weren't altogether free of these aggressively technologized process--pieces either. As a matter of fact, if any body cares to remember a record called "The Medium Is the Massage," with Mar shall McLuhan, you will know exactly what I mean.

Well. I was always fascinated with the notion of process-still am, really--but I tried to convey my fascination in a more clandestine way. I was given to saying things like. "Look here, there are 162 splices in the next movement, but since we've made them very carefully and you're not going to be able to spot them anyway, stop worrying about it." My point, of course, was, and is. that a recording represents something special-that it isn't a replica of a concert experience, that it isn't a memento of some hallowed public occasion, that it is, inherently, an art form with its own laws and its own liberties, its quite unique problems and its quite extraordinary possibilities.

And that brings us back to "process," because, despite all the self-conscious silliness with which that concept has been associated from time to time, it nevertheless implicitly conveys a very important idea-1 was going to say "massage," but skip it. It conveys the idea that the performance, while it may have initiated the chain of events, undergoes a profound metamorphosis as a result of its exposure to that chain, to that network, and the result is a performance transformed, a performance transcended, a performance sent out into the world, if you like, charged with a very special mission. In my opinion, that mission is to enable the listener to realize the benefits of that invisible network, that climate of anonymity which the network provides.

You know, this is a very cloistered environment, this world of the recording studio; that's why I love it so. I don't mean "cloistered" in the physical sense only, though it certainly does share in that aspect of the cloister too. What I do mean is that it's, quite literally, an environment where time turns in upon itself, where, as in a cloister, one is able to withstand the frantic pursuit of the transient, of the moment-to-moment, day-by-day succession of events.

This is, after all, a place where, in the final product, the first take may well be pre ceded by the sixteenth, and where both may be linked by inserts recorded years later.

It's an environment where the magnetic compulsion of time is suspended--well, warped, at the very least. It's a vacuum, in a sense, a place where one can properly feel that the most horrendously constricting force of nature-the inexorable linearity of time-has been, to a remarkable extent, circumvented.

So, if you ask me what's really important about recordings-and I'm speaking now not simply as someone who participates in making them, from time to time, but as someone who also listens to them a lot--I'd have to say that it's the unique ability of a recording to involve the listener in the music or in whatever the substance of the recording happens to be, while at the same time separating that listener from all extraneous biographical data--from all concern with its documentation, its preparations, its performances, its postproduction processes, and so on.

What I'm describing, I think, is not, in the conventional sense, either an active or a passive listener. I'm obviously not describing someone who sits in the stands and cheers on the home orchestra; that may seem like an activity, but it's real') the ultimate in herd-like passivity. On the other hand, I'm not describing someone who flops on a prayer rug and contemplates his navel while waiting for the next chord change in the latest minimalist masterpiece, either. (I hasten to add that I've nothing against prayer rugs, or even navels; I do have a wee prejudice against minimalist masterpieces. but that's another story.) What I'm trying to describe is, for want of a better word, a creative listener-a listener whose reactions, because of the solitude in which they're bred, are shot full of unique insights. These are insights which will not necessarily duplicate or overlap those of the performer or the producer or the engineers; they're insights which initiate a new link in the chain of events, a new link in the net work. It's a link which holds out the possibility that the work we do here doesn't necessarily come to an end when the final product is dispatched from the pressing plant, but rather that, from that point on, it will have consequences which we can't begin to measure, ramifications which we can't possibly attempt to quantify, and that, eventually, like a benign boomerang, the ideas which feed on those consequences, the ideas which, out there in the world of the creative listener, begin to take on life of their own, may very well return to nourish and inspire us.

-HF

------------------------------

Closing the Circle: The Goldbergs Revisited

Reviewed by James R. Oestreich

IT TAKES THE WIND out of one's sails. The text was to have been Glenn Gould's dictum "The only excuse for recording a work is to do it differently" (which should probably not receive wider circulation without the quick qualification he appended in an interview with Tim Page: "If. however, that difference has nothing of validity to musically or organically recommend it, it's better not to record the work at all"); the review, examining the implications of that statement for rerecording, was to have included two other remakes of very "different" Bach recordings--the Brandenburg Concertos of Neville Marriner and Nikolaus Harnoncourt. I started with Gould's Goldbergs. listening first on what I later learned was his fiftieth birthday. As always with him, I found much to infuriate me, but as always, his performance set me to thinking, for hours and even days afterward. If truth were known, I became obsessed with the pianist, reading Geoffrey Payzant's Glenn Gould: Music and Mind and going back to old recordings. Thus, when I heard a week later that he had suffered a stroke, and on the following Monday that he had died, a strong sense of personal irony mingled with all the other imponderables surrounding the life and death of this singular artist. I lost heart for the rest of the project.

What Gould attempts here is nothing less than to grasp the work whole, and it is his remarkable degree of success that ultimately dissolves accumulated quibbles.

When I finally returned to the recording, having totally reconsidered the performance and my initial reaction to it, the tem pos of the aria at beginning and end (very slow and still slower) no longer seemed excruciating. (All to the good, too. Var. 25--whose slowness and oppressive gravity in Gould's famous 1955 debut recording I still do find excruciating, especially in that high-strung context-here proceeds more resolutely and blends well with a mellowed interpretation.) And some of the articulation that seemed merely cute or precious at first now fitted more logically into the kaleidoscope of tone colors.

I have often railed against the lopsided treatment of repeats in a binary structure observance of one, but not the other-and will doubtless do so again. In principle, I would rather have no repeats, as in Gould's earlier recording. Here, however, the issue seems largely irrelevant. Gould takes only some first repeats, those in the canons and a few other variations-thirteen in all. But in the repeats, as elsewhere within variations, he freely shifts articulation, coloration, weight, or emphasis: in addition, he sweeps from one variation to the next after little or no pause (the transitions range from the jolting attaeca into Var. I and the smooth glide into Var. 2 to full stops of various seemingly precisely calculated-lengths).

All of this gives a rhapsodic cast to the work as a whole, making it seem less a row of binary puddles than an impetuous, flowing stream. It's clear that Gould has something much larger on his mind than individual variations.

Yet compelling as his conception is. I suspect that even Gould, in his calmer moments, would not have argued the inevitability of just these first repeats. With an aesthetic so thoroughly shaped by recording, he seems here--with some fifty-one minutes of Goldbergs--too much tied to the constraints of the LP. It would have made for a more expensive, less salable product, of course. but I can't help wishing he had begun with four sides of vinyl spread out before him, to see how much he would have filled-and how he would have done so-in the "best" of all worlds. Though he frequently touted the "limitless possibilities" of recording, it may be that Gould's art, like Stravinsky's, thrived on limitation.

But Bach's doesn't.

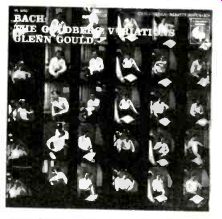

That there are still features here that I don't like (yet?)--a hasty Var. 6. a bottled--Original cover of Goulds 1951 Goldberg. up Var. 19--simply doesn't matter: no performance, even among those I've admired from the outset, has ever furnished more food for thought after a single hearing or after subsequent ones. This time around, Gould has truly made the work his own and given us a performance to live--and grow--with.

Even before the inscrutable twist of fate lent Gould's last major Bach recording still greater significance. CBS had every reason to assume--and must devoutly have hoped--that this renowned Bachian's interpretation would be the version to find its way into many a one-Goldberg household.

The more regrettable, then, that the label's vaunted "new look" accommodates scarcely a word of information about the work beyond its date of composition.

(Room is found for a photo of the older recording's "original cover design," in which the words "An historic record debut rechanneled for stereo" are clearly legible.) The annotations are devoted largely to Samuel H. Carter's paean to CBS's "famous" 30th Street Studio--a curious document that smacks of corporate infighting. Following the final Goldberg sessions, CBS Records (not, be it noted, Masterworks) shut down the studio, "victim of the changed fortunes of an industry that has become as multinational as any other and as competitive." An additional, anonymous note provides further tribute to the studio and, in lieu of useful information, a tease: A thorough explanation of the pianist's "new approach would, according to Gould, entail a complete written anal sis. in an almost book-length essay, of the 'thirty very interesting but independent-minded pieces' that make up the Variations-a fascinating prospect, to be sure." In retrospect, the simple sin of omission becomes a cruel joke.

HF

BACH: Goldberg Variations, S. 988.

Glenn Gould, piano, [Glenn Gould and Samuel H. Carter. prod.]

CBS MASTERWORKS IM 37779 (digital recording). Tape: HMT 37779 (cassette). [Price at dealer's option.]

COMPARISON: Gould CBS M 31820

-------------

(High Fidelity magazine, Jan 1983)

Also see:

Messiah: Reduplication Without Redundancy