Are superlatives exhausted where De Larrocha is concerned?

Two albums of piano music by Manuel de Falla have just been released, one by London Records and one by Musical Herit age Society. The repertoire on the two discs is almost identical, and coincidentally the pianist on both is the same: Alicia de Larrocha.

The MHS recording was made in Spain a few years ago by Hispavox; the London recording is new.

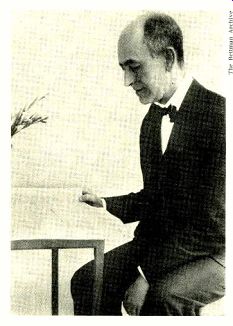

The photographic portrait of Falla on the cover of the Musical Heritage Society album reminds me of the word-sketch that Henry Prunieres wrote of him in 1928: "It is difficult to imagine a figure more Spanish in type than this slight man, thin and alert, whose face seems delicately sculptured in wood; not an atom of fat under the skin of this animated visage; eyes of flame that reveal the intense emotion burning within. Manuel de Falla is the incarnation of passion, imagination, enthusiasm, although an iron will disciplines his emotions." Some years later, in my book The Music of Spain, I drew an analogy between the man and his music: "Not a superfluous note, not an ounce of padding, in the finely wrought, muscular texture of his scores. The sinews of his art are tense, yet flexible; they pass from meditative repose to dynamic action with dramatic rapidity. His creative reflexes respond with sensitive alertness to every emotional impact, yet the process of musical transmutation is achieved with the most painstaking care, with a ceaseless, disciplined striving for perfection." Meanwhile I had come to know Falla in Paris and had occasion to hear him play his own music for piano. He was a fine, sensitive pianist who at the age of twenty-five had won first prize in a national competition in Spain.

All the personal qualities that I have tried to describe were embodied in his playing. Ever since I first heard him play-which was more than forty years ago-I have wondered when a pianist would appear who could transmit to later generations the unique essence of Falla's music as I felt it then. Alicia de Larrocha is that pianist.

She of course possesses greater technical resources than Falla had; but that alone does not explain the marvelous quality of her interpretations. How many times-many more than I care to remember!- have we heard con cert pianists wreak their "virtuosity" on the much-battered Ritual Fire Dance or the Dance of Terror from El Amor Brujo. I must confess that I had reached the point where I never wanted to hear these encore fixtures again-until I heard Larrocha play them. It is silly to speak of "virtuosity" in relation to her playing. Certainly there are innumerable technical details to admire, such as the ineffable clarity and ease of her runs, the expressive articulation of the inner voices, the exquisite nuances of her dynamic palette-but haven't all the fine adjectives and superlatives already been exhausted in writing about Larrocha? For me, the ultimate revelation of her playing is what I must call "poetry"- revealing the inner essence of the music that was only latent until she, "with a ceaseless, disciplined striving for perfection," made us aware at last of its presence.

The immense popularity of the piano transcriptions (by the composer) from the ballets The Three-Cornered Hat and Love the Sorcerer has overshadowed Falla's original mu sic for solo piano-of which he actually wrote very little. It consists of the Four Spanish Pieces (1907), the Fantasia Baetica (1919), and Hommage pour le Tombeau de Paul Dukas (1935). The last is almost never played-because it is not "Spanish." But neither has the Fantasia Baetica been often heard- perhaps because it is not "Spanish'.

enough. Although it relates to Falla's own province of Andalusia-which the Romans called "Baetica"- it marks the composer's transition to the more austere style of his later works, such as El Retablo de Maese Pedro and the Harpsichord Concerto, which reflect the Castilian spirit.

What happened, I think, is that Falla's earlier Andalusian works, with their vivid evocations of cante hondo and the flamenco dances with their fascinating rhythms, aroused expectations in most listeners that are not fulfilled in the Fantasia, with its somewhat archaic and reticent character. It was dedicated to Arthur Rubinstein, who hardly ever played it. It is not a very showy piece, in spite of its many arabesques, down-rushing broken chords, and glissandi passages. The middle section consists of a lovely lyrical intermezzo.

While the Fantasia will probably not become a repertoire piece, now that Larrocha has made it her own its complex beauty can be appreciated by those who do not necessarily associate Andalusian music with shouts of "Ole!" and the clacking of castanets.

The Four Spanish Pieces were begun just after Falla wrote his opera La Vida Breve, in 1905, and were completed after he went to Paris in 1907 (he had planned a seven-day excursion, but remained for seven years!).

Aragonesa has the characteristic 3/8 time and triplet figuration of the jota of Aragon, a fast and vigorous dance. Cubana captures the languorous and sensuous atmosphere of the Antilles, with its evocation of the guajira, originally a folk song of the Cuban peasants (guajiros), with alternating meters of 3/4 and 6/8. In Falla's piece these meters are also simultaneously combined in the right and left hands. Montaiiesa refers to the region of northern Spain known as "La Montana," where the Cantabrian mountains slope down toward the Atlantic. It opens with the sound of distant bells, as though from a hermitage on the mountainside-and how clearly chimed, how unbelievably bell-like, is the sound that Larrocha draws from the piano! As might be expected, A ndaluza is the most frequently played of these pieces. Marked Vivo (tres rhythme et avec un sentiment sau vage), it alternates strongly accented staccato sections with widespread guitar-like figurations and an intensely expressive melody of the cante hondo type. Here again the accompaniment, as in so much of Falla's music, is based on the technique of the guitar.

Of these two recordings, the London offers a wider selection from the two ballets, which Larrocha plays so splendidly that they should not be passed up merely for the sake of getting the attractive but less important Danza No. 2 from La Vida Breve in the MHS recording.

The liner notes for the latter- understand ably unsigned-read as though they had been translated from Spanish into English by some one ignorant of both languages. The liner notes by John Davidson for the London re cording are excellent. I only wish that London had used the portrait of Falla on its cover instead of Goya's painting of two bosomy majas and their sinister male companions very alluring, no doubt, but quite irrelevant to Falla's music.-Gilbert Chase

FALLA: Cuatro Piezas Espanolas: Aragonesa;

Cubana; Montanesa; Andaluza. Fantasia Baetica. Three Dances from El Sombrero de Tres Picos: Danse des Voisins; Danse du Meunier; Danse de la Meuniere. Suite from El Amor Brujo: Pantomime; Chanson de Follet; Danse de la Frayeur; Welt du Pecheur (Le Cercle Magigue); Danse Rituelle du Feu. Alicia de Larrocha (piano).

LONDON CS-6881 $6.98.

FALLA: Cuatro Piezas Espanolas: Aragonesa; Cubana; Montaiiesa; Andaluza. La Vida Breve: Danza No. 2. El Sombrero de Tres Picos: Danza de los Vecinos (Seguidillas); Danza de la Molinera. El Amor Brujo: Danza del Terror. Fantasia Baetica. Alicia de Larrocha (piano).

MUSICAL HERITAGE SOCIETY

MHS 1929 $3.50 (plus 75¢ handling charge from the Musical Heritage Society, Inc., 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023).

Also see: