By Roy Hemming

THE past year has been a big one musically for Dutch pinch-hitters. Young conductors Edo De Waart and Hans Vonk, for example, scored impressively as last-minute replacements with the San Francisco and Boston Symphony Orchestras, respectively (De Waart even becoming San Francisco's new principal guest conductor for 1975-1976 as a result). But the biggest headlines of all went to Dutch soprano Cristina Deutekom (she pronounces it dyoo-teh kahm) when she was called in to replace an ailing Montserrat Caballe for the Metropolitan Opera's gala opening night performance of I Vespri Siciliani last fall: as all opera lovers know, opening night at the Met is a Big Deal.

Miss Deutekom was, of course, no stranger to the Met's stage, having made her much-acclaimed Met debut in 1967 as the Queen of the Night in Mozart's Magic Flute. She has been a company regular ever since, and has toured with the Met several times during its annual spring visits to major American cities. She is also well known to American opera lovers for her recordings, mainly on the Philips label, though some may remember her from London's Magic Flute.

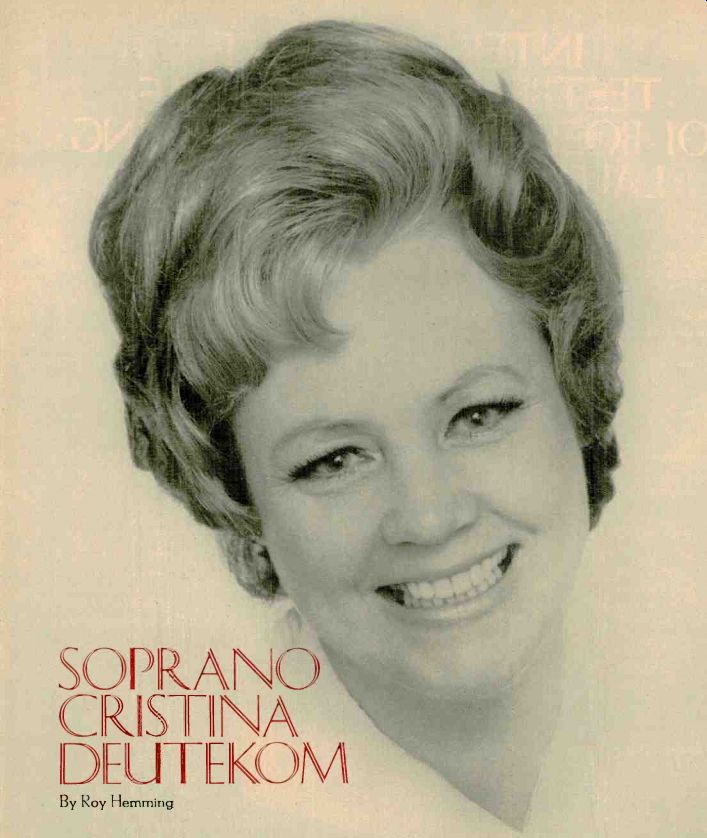

On meeting Miss Deutekom for an interview following a Met rehearsal, my first thought was that she ought to sue whoever designed the album covers by which most American record buyers probably know her. The photos on those albums (or at least the ones I know best) make her look like a plump Bavarian dumpling about to break into The Beer-Barrel Polka rather than the dignified, comely Dutch soprano she is, one who specializes in the less bibulous dramatic-coloratura roles of Rossini, Bellini, Donizetti, and Verdi.

There is no denying that the Amsterdam-born singer is a big woman physically (though there are certainly a number of other popular sopranos who easily surpass her in girth). But her looks and manner, like her singing, are anything but Wagnerian. Instead, she has a typically Dutch, down-to-earth approach to herself and to her career.

"I was born with the ability to sing an F--do you say it that way in America? Anyway, I'm born that way," she adds with a warm smile. "It's also my character that when I do something, no matter what, I try to do it perfectly. So when I started singing as a child-as long as I can remember I have liked to sing- I felt I must try to develop my voice the best I could. So I began to study, and to sing in choruses and operettas in Amsterdam." To pay for her lessons, she worked in an Amsterdam hosiery shop.

When did she first realize that singing was going to be a career? "When I got my first money for singing," she replies with a laugh. "Actually, I was already singing with the Netherlands Opera be fore I thought seriously of a professional career- certainly of an international career."

The Queen of the Night also served as her operatic debut in Amsterdam in 1963. "I did the part with the company a year before my official debut, at a performance for which there was no press or critics in the audience. I'm very glad it was that way because just before I was to go on, I somehow got my knife stuck in my dress. I got so carried away with trying to free it that I didn't hear the orchestra--and completely missed my cue! The conductor stopped and waited. I was so embarrassed. It's a good thing there was no press there that night!"

She didn't miss her cue for her official debut the following year, and the re views were good indeed. Her husband, an industrial photographer who has since become her road manager, encouraged her to accept invitations to sing the Queen of the Night in Vienna, Munich, Stuttgart, Venice, London, and San Francisco. In addition to singing the title roles in Lucia di Lammermoor and Norma, and Donna Anna in Don Giovanni, she has also gone on to star in revivals of many long-neglected bel canto operas-operas that have lain neglected because there were so few good singers capable of handling them. She has recorded two such works for Philips: Attila and I Lombardi, both by Verdi.

"It's interesting to do many of these roles," she says, "but if you cannot go on to perform them more than a few times, it becomes something of a waste. It took me two years, for example, to study and learn Rossini's Armida for the Fenice Theatre in Venice. But no one else does it. That's a real problem for a singer--all the time and study for something that just lies there unused." How does she feel about taking over a role that has been identified in the public mind with another singer-such as re placing Caballe in the Met's Vespri Siciliani? "Maybe it's a problem for the audience, but not for me," she says. "Perhaps they compare, but I cannot approach any role that way. When I study a role, I do not listen to records to hear how other singers do it. I will listen to records, however, to learn how the orchestration sounds before I get to the orchestral rehearsal. That can mean something after rehearsing only with the piano. But I do not listen to the voices with the idea of doing something either like or differently from another singer. I try always to keep my own vision, my own conception of the part.

"I think it's something like it is with sports," she continues. "Take this American swimmer in the last Olympic Games, Mark Spitz. He was a really good swimmer, with his own style. That doesn't mean that in the next Olympics the best swimmer must perform in the same style as Mark Spitz did. Now, with music, Placido Domingo can make a movement or do something you'll like very much--yet that same thing can look silly on another tenor.

"Stylistically, I think I'm somewhere between the Italian and German traditions. The Italians, for example, like to take all the high notes and hold them for a long time. The Germans are just the opposite in their exactness. They say, 'It's written this way and we do it this way.' In Holland we try to find our way between the two. I think in America it is moving more and more toward the Italian way. I find Americans today like their singers to show off a bit-not as much as in Italy, but a bit more than in Holland." Of her recordings, Miss Deutekom is proudest of a set of Mozart arias re corded in Europe by EMI but not yet released here. "It won an award in Paris, but that's not why I like it best," she says. "I think it has the most beautiful sound, technically, of all my recordings." She is less happy about an album of Viennese waltzes. "Technically it is not very good. I wish they would take it out of circulation or let me do it over again." Her objections have nothing to do with the album's content. Quite the opposite.

"I really like the music. I like waltzes, I like Strauss and Gershwin. I object when people call it just 'light' music or say that singers record such music only for money. Actually it's very hard music to sing well, and hard to find a conductor who can do well, too." There's another form of snobbery that also bothers Miss Deutekom. "Some times I am asked if there is a different audience response in different cities or in different opera houses. To me, that's less noticeable than the type of audience you get on certain evenings--when you get only the snob audience. They're the same the world over! They don't come to hear the opera, but to show off them selves, to see and be seen.

"I remember one performance of La Favorita before such an audience in Italy. I became so upset by the behavior of this audience- walking about during the performance, talking and making all kinds of noise-that I finally walked out.

Not in the middle of the act, but at the interval [intermission]. It was a pity, for it was a very good performance. But they were so ... so ... " she pauses and throws up her hands. "They were such snobs I just could not continue." Her action was certainly atypical, for members of the Met Opera staff have told me that Miss Deutekom is anything but the temperamental prima donna that she is, in fact, regarded as one of the most professional and cooperative sopranos around. And she herself told me, "I think it's impolite to act like a prima donna. You cannot scream at people just because you've had a bad day. If you don't feel well, stay home. Stay home and don't bother anyone. If you're nervous, okay-there are a lot of people who can understand that. But that's no reason ever to be nasty." LIKE most of her Dutch compatriots, she has a high regard for good manners.

She is bothered by the lack of them in some opera audiences today-especially the booing that's been heard more and more frequently at the Metropolitan Opera in recent seasons. "I think it's terrible." she says. "I myself have not been booed, but it is unfair to all the singers on the stage when someone is booed. First of all, nobody gets hired by a house like the Met unless they are of a high professional quality. Now, if someone sings badly at such a house on a particular evening, there is always a reason. It may not even be the singer's fault. I know the audience does not pay to listen to a reason, but they should appreciate that there may be circumstances beyond the control of any given singer or even the management that evening." But, I asked, when an audience is paying $20 or $25 a ticket, isn't their dissatisfaction understandable? Miss Deutekom replied firmly: "At $25 a ticket, I think they can afford better manners."

Also see: