Julian Hirsch tells you what you should know before you 90 out shopping

WHETHER they cost $15 or $1,500, all record players are designed to do the same thing, and by and large they do it in the same way: the turntable platter rotates at a specific speed while a tone arm holds a phono cartridge positioned over the record in such a way that its stylus can follow the inwardly spiraling record groove. That sounds simple enough, but what is the difference between doing this well and doing it badly, be tween a high-fidelity record player and, say, a $15 kiddie phonograph?

The platter of a true hi-fi record player provides a substantial, physically inert record-support surface that rotates without vibration at a true and constant speed; the cheap phonograph uses a small stamped or molded resonance-prone platter rotated by a drive system with inherent speed fluctuations (wow and flutter) and mechanical vibration (rumble).

A quality tone arm is designed to be non-resonant, to have both minimum mass and great structural rigidity, and to be as friction-free as possible. In addition, precise and stable adjustments are provided to optimize the stylus-to-groove relationship. This includes adjustments for antiskating force and vertical and lateral tracking angles. The cheap player has a stamped sheet-metal or plastic arm with little means of adjustment.

These are of course the extremes of the entire record-player spectrum, but even within that smaller group of machines referred to as high-fidelity instruments some significant differences may exist. The trick, therefore, is to learn to distinguish (1) those differences that might have some bearing on actual performance from (2) those that represent no more than a cosmetic variation or a different (but perhaps equally valid) design philosophy. Putting this insight together with a clear under standing of the various operating and convenience features will usually lead a buyer in the direction of the machine that will serve his system and his record-playing habits best.

Platters

Not too long ago, a turntable was likely to be evaluated mostly by the weight of its platter: the heavier the better. Today it is more widely under stood that weight itself is not the key factor-the weight to drive-torque ratio is. A heavy platter is useful because its inertia resists being affected by motor-speed or drive irregularities. But as the motor becomes smaller in size and torque, the platter can be made lighter and still provide the equivalent stabilizing effect.

If all types of motors were equal in vibration and speed regularity, it might be possible to specify an optimum weight-to-torque ratio that would hold for almost any high-quality record player. Unfortunately, motors vary in these respects, some of them requiring larger "flywheels" to smooth their rotational roughness. As long as the de signer takes this factor into account, it is possible to achieve a very high level of turntable performance with a motor that would at first seem too unsophisticated to bother with.

Quite recently some design attention has been focused on acoustic damping of the platter-that is, eliminating any tendency for its structure (usually formed of aluminum or magnesium alloy) to resonate mechanically, or at least isolating the record (and hence the cartridge) from any such resonance.

Sony's PS-4750 has a large platter molded entirely out of a plastic material that is inherently well damped, and other manufacturers have used similar materials to fabricate turntable bases and other structures known to be vibration-prone. Record-supporting mats made of some rather exotic materials have also begun to appear. Although we at Hirsch-Houck Labs have not been able to measure the specific benefits of these materials, we are at least certain they don't do any harm.

Drive Systems

At one time the type of motor used in a given record player could be a strong selling point in its favor. The matter receives somewhat less attention today because motors have, in general, improved tremendously and because other factors are assuming greater relative importance. However, drive systems (the linkages that couple the motor's rotating element to the platter) continue to be an important consideration for buyers. Three systems are in general use: idler drive, belt drive, and direct drive. There is also an occasional combination system, such as belt/idler drive. In the idler system, a rubber or soft-plastic disc ("puck") presses against both the motor shaft and the inner rim of the platter, transferring the rotational force and gearing the motor speed down in the process. In belt drive, a continuous belt links the shaft and a circumference of the platter; the circumference can be the outer rim of the platter or, as it is more often, a ring or other circular protuberance on the platter's underside. For direct drive, the motor's shaft becomes, in effect, the platter's central spindle, and in some of the direct-drive machines the rotating part of the motor (the rotor) is an integral part of the platter. In others, the platter rests directly on the rotating element.

The type of drive system employed by a record player also has a bearing on how playing speed is changed. Idler drives almost invariably make use of a stepped motor shaft, the rubber-rimmed idler wheel itself being physically shifted from one shaft diameter to another to alter the drive ratio and hence the platter speed (sometimes each step is gently tapered so that the idler's position can be continuously varied across the taper to provide a vernier speed adjustment). Similarly, most belt-driven machines employ a stepped motor pulley; the belt is simply shifted from one pulley diameter to another. Often there is an external control that engages the belt and guides it to the new diameter, although in some few cases the platter must be removed and the belt shifted by hand--a simple if inconvenient process. Some belt-drive machines-notably several B.I C. and Thorens models--provide for an electronic speed change of the motor, while the Dual belt-drive units have motor pulleys that physically expand in diameter. Finally, direct-drive turntables must of course have variable-speed motors, since there is no drive linkage to provide a set of different drive ratios.

Tone Arms

Among the many factors that should be explored when considering tone arms is the "feel" and operating convenience of the arm. Unless you plan to buy a fully automatic turntable and use it only as such, you will have to handle the arm from time to time, and you'd like the experience to inspire confidence. With a cartridge installed and the correct tracking force applied, the arm should exhibit no tendency to float out of your grasp when you raise it by the finger lift. Also, the cueing mechanism, often provided to raise and lower the arm, should not cause it to bounce or to shift laterally more than a groove or two. And there is more to it than merely "inspiring confidence," of course. A tone arm that tends to "get away" from your hand is as likely to try to the record surface warp. In other words, this kind of behavior is an indication of excessive mass in an arm--a fault that can have considerable effect on performance.

"In an effort to reduce mass, some audiophiles have gone so far as to take hacksaws to their tone arms ...

The basic function of the tone arm is of course to serve as a support for the cartridge, maintaining proper record- playing geometry in the process. Other wise, the tone arm should remain very much out of the act, so to speak. though that is not as easy as one might expect. No arm has absolutely friction-less bearings. and there is therefore al ways a slight (but essentially negligible) resistance to movement in the pivot structure. Conventional tone arms also exert an appreciable (and undesirable) sideways force on the stylus, and this is known as skating force. Finally, arms and arm-cartridge combinations have mechanical resonances at east one major low-frequency resonance and possibly several lesser high-frequency ones. All these can have their effect on the reproduced sound, either directly or indirectly.

In the interest of correct playing geometry, the tone arm should keep the long axis of the cartridge (as viewed from above) in a condition of tangency to the arc formed by the record groove, and the top reference surface of the cartridge (as viewed from the side and in front) parallel to the record surface. Perfect tangency cannot be achieved with a conventionally pivoted tone arm at all points on a record side. But if the manufacturer pays correct attention to the geometry of his design (the angle of the bend or “offset" in the arm head that holds the cartridge and the distance from the arm pivot to the stylus tip and turntable spindle), an arm with a typical pivot-to-stylus length of about 8 or 9 inches can achieve perfect tangency where it counts most and acceptable tangency elsewhere. In most cases the user will have to trust the manufacturer or published test reports on a product to determine whether the variables have been properly handled.

Parallelism of the cartridge's top and the record surface is relatively easy to attain in a single-play turntable and next to impossible in a record changer, because the record stack building up on the platter keeps changing the elevation--and hence the vertical angle--of the cartridge. Typically, the arm and cartridge achieve the ideal condition of horizontality midway through a stack of records. But a number of machines permit you to establish the proper geometry for a single record on the platter as well, either through a mechanical control that resets the front-to-back inclination of the cartridge in the headshell or a similar mechanism that lowers the height of the pillar supporting the arm's pivot assembly.

Either system can work well enough to equal the alignment accuracy of a single-play turntable. In any case, it is the view of most authorities that minor errors in record-playing geometry are audibly inconsequential.

The pivot bearings of a good tone arm must have low friction and be very durable. Today, most are, and forces acting on the arm from pivot friction are likely to be trivial compared with grosser phenomena such as skating force. Skating force is in effect when ever the stylus is in contact with the rotating record surface; it acts inward, to ward the center of the record, pulling the playing end of the tone-arm in that direction. The cause of skating force is simply the record groove's drag on the stylus which, pulling against the pivot assembly through an inwardly bent arm, creates a component of force directed inward. The problems it creates are (1) lowered tracking force on the outer (right channel) groove wall, which can lead to stylus mistracking and distortion when that wall undulates vigorously, (2) a lateral displacement of the stylus of a highly compliant cartridge, which may (but does not al ways) have undesirable consequences, and (3) uneven stylus wear.

Resonances

We come at last to a great gray area in tone-arm performance: resonances. In the record-playing situation a tone arm can be looked upon as a freely pi voted mass supported at one end by a tiny spring, the compliant stylus assembly. Such a mass-spring system will inevitably have a preferred frequency of resonance-the frequency at which it prefers to vibrate or oscillate if disturbed. It is bad news if this resonance frequency happens to correspond to some frequency at which record warps tend to occur (around 4 Hz for a 12-inch, 33 1/3-rpm record, for example), be cause the tone arm will then do a lot of bobbing and weaving-far more than the warp itself would cause. It is not much better to have a much higher resonance-25 Hz, perhaps-because this begins to enter the range of recorded material on the disc and will cause audible bass-response irregularities.

The best place for a combined arm-cartridge resonance is therefore about 10 Hz or a bit higher. This frequency range amounts to a sort of "neutral zone"; it is below the range of recorded music and above the range of the worst record warps. But how does one get the resonance to fall there? By "tuning" the arm-cartridge combination. An arm with high effective mass and/or a cartridge with a very compliant stylus assembly will lower the resonance frequency; a low-mass arm and/ or a comparatively stiff stylus assembly will raise it. It is therefore possible to match the arm to the cartridge (or vice versa) to obtain the resonance frequency of your choice-within limits. In practice, modern cartridges offer such high compliance that it is an unusual arm that is light enough to yield a resonance frequency much above 8 Hz. But record-player and tone-arm manufacturers are at work on the problem.

Since mass at the extremities of the arm contributes more to effective mass than weight near the pivots, such mass-adding features as detachable cartridge shells are being eliminated (as in one version of the famous Shure/SME arm), or the bulky connector that permits such detachment is being moved closer to the pivot assembly (as in the new Thorens arm and the arm on the Harman-Kardon/Rabco ST-7 radial-tracking turntable).

A basic technique for coping with resonance is damping, and it is used in all electronic, electromechanical, and mechanical structures where resonances have to be controlled. In the tone arm, various materials and combi nations of materials have been used to prevent or minimize higher-frequency resonances within the arm structure.

To cope with the lower-frequency resonances, a few arms incorporate 'some type of viscous damping at or near the pivots. The counterweight at the tone arm's rear is usually isolated by a compliance, the purpose of which is to pro vide a deliberately resonant structure that is tuned to, but out of phase with, the basic tone arm/cartridge resonance.

The more expensive Dual models go a step further by using a double-compliance counterweight designed for staggered resonances. The practical result is a single broadly tuned, well-damped resonance that can effectively cancel a broad range of arm-cartridge resonances. This arrangement achieves many of the goals of viscous damping without its problems--fluid leakage and reduction of the arm's freedom of movement.

In an effort to reduce mass, some audiophiles have gone so far as to take hacksaws to their tone arms at the risk of awakening another resonance drag on: structural resonances. Almost any tone arm has inherent structural resonances, and the battering the cartridge stylus takes from the undulating record groove may be enough to excite them.

The resonance may occur because of some tendency in the arm shaft to flex or twist in a complex way, or because of some structural looseness--an inadequately secured cartridge shell or cartridge, for example. No arm with serious structural resonances survives very long on the high-fidelity market, but minor resonances are frequently uncovered by laboratory tests and are also heard (as frequency aberrations) by audiophiles. As a rule they do not sound terribly objectionable, but we suspect that they are responsible, at least in part, for the growing conviction that tone arms can "sound different." As an arm becomes less massy (and therefore more desirable for use with a high-compliance cartridge), it also becomes more subject to structural resonances unless its construction can be made very rigid. That is why the search is on for a material that is both light and structurally solid. Carbon fiber, a relatively new and exceptionally stiff sub stance, has been the choice of such manufacturers as ADC, Infinity, and Sony, the first two of which now offer unmounted arms with tapered carbon-fiber shafts of very low mass. The fu ture will almost certainly bring even more developments in this area.

Suspensions

Just as it is usually desirable to isolate the platter from the motor vibration, it is also wise to isolate the entire record player from its environment, which may he a source of physical jolts and vibrations, perhaps even acoustically induced vibration from the loud speakers. After all, the cartridge stylus cannot distinguish between vibrations imposed on it by the music in the record groove and those from the external source transmitted through the record.

It will reproduce both with equal competence. If the source of the external vibration is the speakers, an acoustic-feedback situation can be set up.

----------------------

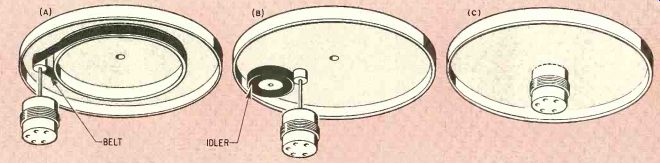

A LOOK AT THE DRIVE SYSTEMS

Right, simplified views of the three major turntable drive systems: (A) belt. (B) idler, (C) direct

IDLER DRIVE: Simple and reliable, idler drive is capable of providing the extra torque needed to operate a record-changing mechanism. Until a few years ago, therefore, all record changers used idler drive, and this time-honored system became refined to the point that in the better models, any performance limitations are below audibility. However, except for the direct-drive system, it provides the least isolation between the motor and the turntable platter. This means that an imperfectly manufactured idler wheel (or one whose rubber has deteriorated with time) can result in appreciably higher and audible rumble and flutter levels.

BELT DRIVE: In belt drive, the flexible belt-soaks up" much of the motor's vibration and speed variations (flutter), so that a well-designed belt-driven turntable usually has lower rumble and flutter than one driven by an idler. There are, however, numerous exceptions, and a really good idler-driven record player is likely to be better than an inexpensive belt-driven model. Rather recently, designers have found ways of getting around the "loose" belt coupling, thereby assuring the availability of enough torque to make belt-driven changer mechanisms possible. Such manufacturers as ADC, B.I.C., Dual, Garrard, Miracord, Philips, and Realistic have all devised belt driven machines that change records. Philips, however, uses a separate mo tor to operate the changer mechanism.

DIRECT DRIVE: The direct-drive system, in which the motor drives the platter directly, provides the least mo tor isolation of all. However, the low operating speeds of the direct-drive motors (which are the same as the record-playing speeds) insure that rumble will occur only at very low frequencies where it can be easily and effectively filtered out. On the other hand, design virtually mandates the use of electronic control circuits to ensure, speed ac curacy and stability. Motional-sensing feedback is therefore used in all direct-drive machines, with some type of sensor responding to the rotational rate of the platter. The sensor's output is fed to a control circuit that governs the drive signal being fed to the motor. Hence the direct-drive machines achieve mechanical simplicity (there is often only one moving part--the platter/rotor) at the expense of some electrical complexity, since the sensing, feedback, and drive circuits are likely to contain a considerable number of transistors (or integrated circuits) and passive components. Technics has introduced several models ins which al most all the electronic control functions are taken care of by a single integrated circuit.

----------------------

"... fortunately, the choice today is not so much between unavoidable evils as between enticing attractions."

The speaker sound is picked up by the turntable, is fed to the cartridge, and passes through the whole sound system again--where it is amplified, sent through the speakers once more, back to the turntable, and so on. In severe cases the whole thing "takes off" like a public-address system with a severe case of "howlback." More usually, the audible effects are rumbling, a blurring of the sound, and a sort of false reverberation-all of which are often blamed on the wrong cause.

While not guaranteed to prevent acoustic feedback and similar ills totally, a well-designed turntable suspension is likely to be of some help. Many manufacturers make use of damped springs, while others like B.I.C. use resilient, rubber-like mounts for their motor-boards; Stanton has magnets, so that the platter is literally floated by the force of magnetic repulsion; Infinity's Air Table also has a floating platter, this one supported by air forced by a small outboard compressor into the chamber where the platter bearing would ordinarily be.

Mostly because of their physical de sign, direct-drive turntables usually have the entire mechanism, base and all, supported on resilient feet. This makes use of a very solid, resonance free base advisable. For machines using idler drive, the usual scheme is to float the entire motorboard on springs, so that it is isolated from the base. A few direct-drive machines also use this technique. Belt drive permits a number of approaches. A good one is an internal, spring-supported rigid sub-frame that in turn supports just the platter and the tone-arm base, isolating these two elements from the motor and motor-board and also making sure they do not move relative to one another.

Whatever type of suspension a record player uses, considerable variation in its effectiveness is possible. Since this book is not easily judged by its cover, we try, in our record-player test procedure, to measure and describe the machine's sensitivity to acoustic feed back and external vibration.

Innovations

Taken all in all, the record player is really a simple electromechanical theme upon which a great many elaborations can be wrought. The changer, for example, began life as a justly maligned instrument of record torture, evolved into the gentle and sophisticated "automatic turntable" with indisputable high-fidelity credentials, and is now emerging as a marvel of automation. The most conspicuously automated changer to date is the ADC Accutrac +6, a machine that, under pushbutton control, can not only play any band of any record in its "stack" in any desired sequence and for any number of repetitions, but can also cycle its way both ...

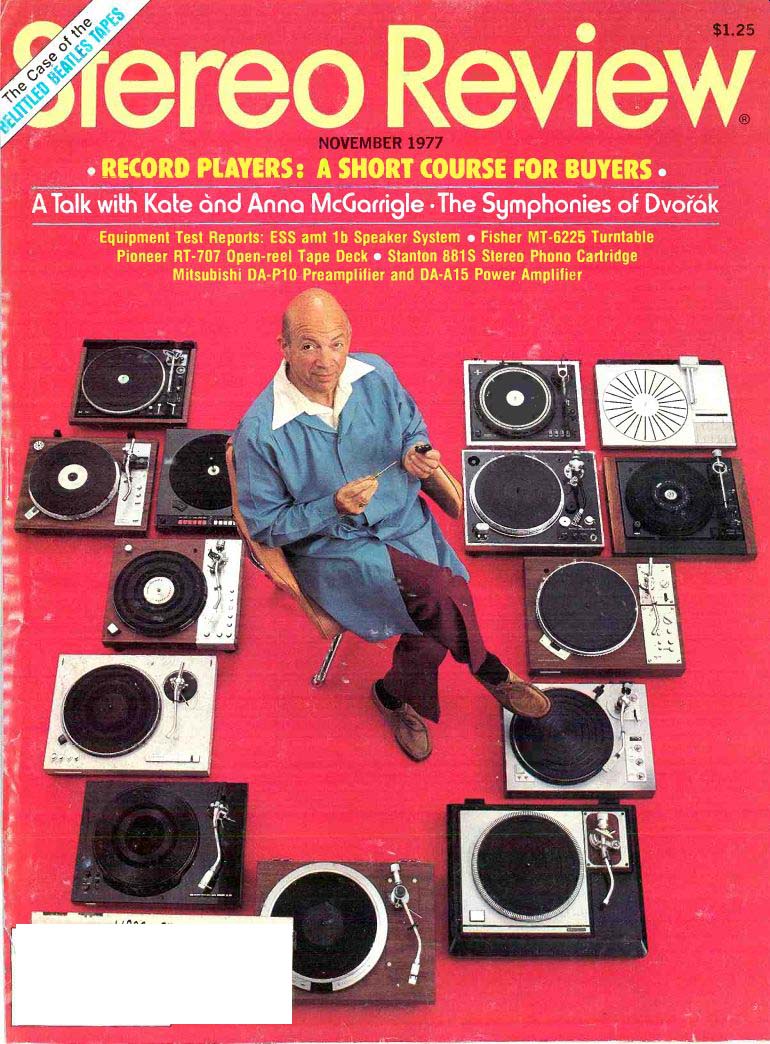

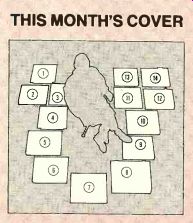

--------------------- THIS MONTH'S COVER TURNTABLES on the front cover

are, by the numbers, (1) Dual 721C, (2) Fisher MT-6225, (3) ADC Accutrac

+6, (4) Marantz 6300, (5) Kenwood KD 550, (6) Sansui SR 929, (7) JVC QL-10,

(8) Technics SP10 II , (9) Garrard GT 35S, (10) Pioneer PL 570, (11) Sony

PS 8750, (12) B.I.C. 1000, (13) Philips GA 222, and (14) B & 0 Beogram

4002.

----------------------

... forward and back through the stack, making any record accessible at any time. And this unprecedented flexibility is available not only at the turntable itself (through a control console built into the machine's base) but from other locations in the room (by means of a re mote-control unit resembling a pocket calculator).

The Accutrac +6 is a belt-driven changer. Technics by Panasonic now manufactures three direct-drive changers, so that there are not now many features of the best single-play turntables that cannot also be found in some record-changing turntables. As a bonus, most changers can also be operated as single-play machines.

Meanwhile, the popularity of true single-play or "manual" turntables is, if anything, growing, and they have evolved along several different lines.

Some have acquired automatic features-anything from a simple tone-arm lift at the end of a record to tone arms with completely automatic cycling and platter speeds that shift from 33 1/3 to 45 rpm according to record diameter (as in the Philips GA 222).

Others have made excursions into technical refinements such as the straight line-tracking tone arm. In such an arm the pivot assembly does not remain stationary. Instead, it moves slowly along a track, keeping up with the cartridge as it moves in toward the record center.

Straight-line-tracking arms are straight, having no offset bend like conventional tone arms, and, since they do not give rise to any skating force, antiskating mechanisms are unnecessary. They also have the potential of providing virtually perfect record-playing geometry.

The Harman-Kardon ST-7 and Bang & Olufsen 4002 turntables have the only extant straight-line-tracking arms at present, but at least one more is scheduled for introduction in the foreseeable future. The arms are reasonably complex, requiring special servo-mechanisms and motors. The single-play B&O 4002 is also a highly automated turntable; playing speed is changed in response to record diameter by means of a sophisticated optical system, and the arm is designed never to be touched by human hands. The whole machine is so carefully integrated that only one cartridge can be used in the arm B&O's own top-of-the-line MMC 6000.

A deluxe turntable today, whether changer or single-play, is likely to have the following features: a tone-arm cueing mechanism to raise or lower the arm at the pull or push of a lever (which should be evaluated for smoothness and accuracy of operation); speeds of 33 1/3 and 45 rpm, and possibly a third speed; fine-tuning speed controls that can vary any of the speeds up or down by a few percentage points; and some sort of indicator to show when the proper speed is exactly "on." Stroboscopes are used most widely for this last feature, and they work well. Both JVC and Technics have digital speed indicators, so that the actual numbers "33.33," etc., are illuminated when the speed is correct. Pioneer's top turntable, the PLC-590, has a meter for speed indication.

Other turntable features and "nice" touches abound. For example, there is a minor trend getting underway (Setton and Visonik) to locate all controls on the front edge of the turntable base so the user needn't reach over the motor board (or remove the dust cover, if it is ...

-----------------

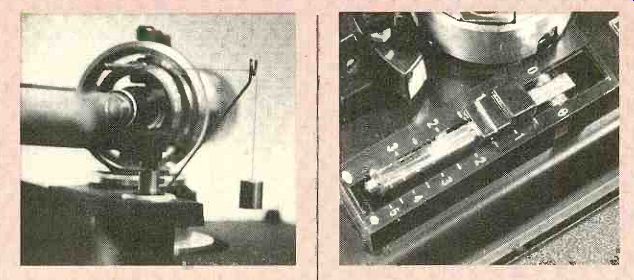

DEALING WITH SKATING FORCE

---------- The hanging-weight and weighted-lever systems at right are

only two of the many types of antiskating devices.

IN modern tone arms, skating force is I countered by an equal but oppositely directed force. A tiny weight hanging from a thread that passes over a shaft or pulley can apply a steady pull on the arm in the outward direction. So can a weighted lever gently opposing the arm's inward rotation, or a calibrated coil spring, or a magnetic repulsion system. All but a very few high-fidelity tone arms have some sort of "anti-skating" mechanism, many of elaborate appearance, with adjustments calibrated for different stylus shapes and special playing conditions. But it must be admitted that the counterforce applied by any of, the systems at any one moment is at best only approximately correct, because skating force varies constantly with, among other things, the "loudness" of the signal in the record grooves. In addition, some of the antiskating systems probably impose as a much friction on a tonearm's lateral movement as would a very inferior set of pivot bearings (only in the rarest cases is the arm's freedom of vertical movement affected). But it is in a good cause, and most authorities now agree that some skating compensation, approximate though it may be, is usually better than none at all with today's cartridges.

-----------------------

... in place) to get at the cueing lever or some other switch. Record players differ greatly in the ease of installation and alignment of the cartridge. The variations are too many to list, but a well-thought-out cartridge-installation scheme is a boon, particularly to any one intending to change cartridges frequently. Finally, although the vast majority of record players come with pre-installed arms, there is a definite rise in the number of top-of-the-line turntables having no arms-a chance for the user to install the tone arm of his choice.

With record-player performance as uniformly good as it is today, small features and conveniences are more than icing on the cake. In some cases they will be compelling factors in an intelligent choice between products, and as such they deserve close attention.

Specifications

A few notes about specifications are appropriate in conclusion. Specs are, alas, not always as helpful as they might be, because they are derived ac cording to a variety of "weighting" systems that are not directly comparable. Sometimes (but not always) the weighting system used is identified on the specification sheet (DIN A, DIN B, NAB, etc.), and you can then make some sort of comparison with other products rated according to the same system. But comparisons involving different weighting systems are not possible with the information provided.

According to the weighting systems used by Hirsch-Houck Labs, short term speed irregularities (wow and flutter) are usually under 0.15 percent even in rather low-price record players ($100 or so). This amount of fluctuation will usually not disturb any but the most critical listeners. Above $150, most record players have less than 0.08 percent flutter, a negligible amount.

Within a given price range there are no clear distinctions between single- and multiple-play turntables in this respect.

Rumble is, of course, almost always higher in less expensive turntables. Hirsch-Houck Labs tests, based on the ARLL weighting curve, show that a rumble level of-50 dB or better is generally quite satisfactory if the loud speakers used do not have an unusually powerful output below 50 Hz. Most turntables priced from $100 to $200 will have rumble levels of-54 to-56 dB when measured in this manner. If your speakers have extended bass response, look for a turntable with a -58 to -62 dB rumble level (ARLL weighting); it is unlikely to be audible with any speaker.

In general, direct-drive turntables have the lowest rumble (and lowest flutter), with levels of-60 to-62 dB being typical. However, there are several belt-driven units costing $200 to $300 that actually have lower rumble than all but a few of the best direct-drive machines, so it is dangerous to make sweeping generalizations. How ever, it is true that in turntables you get just about what you pay for, so do not expect a $100 record player to perform like one costing $300 or more. On the other hand, because many records have a certain amount of built-in low-frequency noise themselves, it is quite possible that much of the time you will not hear the difference be tween a $100 and $300 turntable. In any case, as is true with most audio components, you ultimately reach the point of diminishing audible returns as you approach the very-high-end equipment. Just where that point is, each buyer must decide for himself.

To sum up, choosing a turntable is not easy, and it becomes less so as available models proliferate. Fortunately, the choice today is not so much between unavoidable evils as between enticing attractions. It makes sense to indulge yourself a little if you can, be cause a record player is something you've got to operate--at least to a certain extent--by hand, and being regularly balked by discouraging or frustrating construction quirks is going to be no fun. But even if your budget won't stretch to accommodate the ultimate, the possibilities are rich and varied. Dive in.

---