By Bruce Bartlett

The increasing use of digital techniques in recording musical ensembles seems to have refocused the attentions of engineers and listeners alike on the two big microphone questions: Where and How many?

WHY does one recording of a given musical work sound more "real" than others? Why is another more exciting sonically? The differences can usually be traced not to the recording technology (analog, digital, or direct-to-disc) nor to the choice of home playback equipment, but to simple changes in micro phone placement at the original recording session.

Miking technique can radically alter most sonic aspects of a recording: perspective (the distance to the ensemble); ambiance (a sense of the acoustics of the concert hall or studio being used); the depth, stage width, and definition of the acoustic (stereo) image; orchestral balance and tone quality; and even per haps the perceived musicality of the performance. As home stereo systems become more sonically "transparent," it becomes easier to discern the effects of different microphone techniques on the recorded sound and music. To understand where many sonic differences among recordings originate and to de fine the compromises involved in making a "high-fidelity" recording, let's pretend we're going to produce one.

Imagine we've been given the task of recording an orchestra in such a way that it sounds "real" when reproduced over loudspeakers in a home listening room. Specifically, the goal is to place microphones so as to create in the listening room an accurate and pleasing sonic image of the orchestra (and the concert hall's reverberation) as heard from an ideal seat in the audience (note that "accurate" and "pleasing" may not necessarily be compatible aims). To find the best mike positions we'll use intelligent trial and error, making frequent comparisons between playback of the recording and the live sound to help us chart our progress.

The first step in achieving a pleasant sound is to record the orchestra in an acoustical environment appropriate for the music. For example, the reverberation time of the recording locale should be relatively long for large, massive works (Mahler's Symphony of a Thousand) and shorter for more intimate pieces (a string quartet). Also, the tone quality of the reverberation should be neither too boomy nor too shrill. Excel lent-sounding halls are not, to be sure, always available, but for the purposes of this experiment, we'll assume that the recording is taking place in a suit able environment.

As the orchestra is playing, we walk around the hall seeking an ideal seat in the audience, one where the sound is musically well balanced and where the direct sound from the orchestra blends in pleasing proportions with the concert hall's reflected ambiance. The position of this ideal seat depends on the hall acoustics, the size and layout of the ensemble, the particular piece of music, and the taste of the listener. One reason why different recordings of the same piece sound different immediately suggests itself: not all recording producers prefer the same ideal seat.

Microphone-to-Source Distance

It seems logical to place a special stereo microphone (or a pair of conventional microphones) at ear height in what we consider to be the ideal seat and record the performance from there (see Figure 1). How would the reproduction of the orchestra sound recorded from there compared with what we would hear "live" sitting in the same seat? Probably too distant, blurred, and over-reverberant. Why? Reverberation in a concert hall comes to the listener-and the microphones from every direction. Our two ears can easily sort out the direct sound of the orchestra in front from the reverberation coming to us from all around. During playback of a recording over a stereo system, the reverberation is no longer heard from all sides, for all the "hall sound" comes from the space between the two stereo speakers along with the direct sound of the orchestra. Direct sound and reverberation are thus mixed together with minimal directional differences. Our ears can no longer separate the two, so the "excessive" reverberation gives a washed-out, distant-sounding perspective to the music.

To achieve a more natural sound, the microphones must be moved closer to the orchestra to pick up more of the direct sound and proportionately less of the reverberation. As the mikes are moved toward the ensemble, the sound becomes "closer," more "intimate," "detailed," or "dry." The scraping sounds of the strings and the key noises and breathing of the woodwinds be come more obvious, as do creaking chairs and turning pages. A slightly more distant mike placement, although still closer-in than the ideal seat, will give a more blended but somewhat veiled and faraway orchestral picture.

There are some stereo microphone techniques (such as the crossed-figure-eight "Blumlein" system and binaural "dummy head" recording) which are claimed to produce acceptable direct-to-reverberant sound ratios when placed in the best live-listening position in the audience. In general, however, because microphones do not hear the same way humans do, they must be placed somewhat closer to the orchestra than our favorite audience seat if the recorded result is to be pleasing.

The music itself should contribute some clue as to a suitable microphone-to-source distance: closer for incisive, rhythmically motivated works (such as Stravinsky's Rite of Spring), more distant for slow-moving, harmony-based compositions (a Bruckner symphony).

Monitoring through headphones or loudspeakers while the microphones are placed at various distances from the ensemble (typically 5 to 20 feet from the front row of musicians) will aid in the selection of a spot where there is a tasteful balance between concert-hall ambiance and the direct sound from the orchestra. The goal is to achieve the same audible sense of distance to the ensemble (the "perspective") as would be heard from the ideal seat we chose earlier.

Microphone Height

Let's try recording from a spot (Figure 1, location 2) closer than the ideal seat. The sound is much clearer now, but the instruments in the front rows of the orchestra are much too loud com pared to those in the back rows because the back rows are proportionately much farther from the mikes than they are in location 1. Raising the microphones several feet on a stand (a typical height would be around 15 feet) will help restore the front-to-back balance to what would be heard back in the ideal seat. For smaller groups, those with little depth to the ensemble, the microphones can be placed lower, sometimes even on the floor.

Frequency Balance

Now, in our attempt to get ideal-seat sound quality, we have placed the mikes close to the orchestra but high (Figure 1, location 3). After recording from this position we notice that the playback sounds "brighter" (stronger in the high frequencies) than the live orchestra does.

The duller sound heard at location 1 is partly owing to the air's absorption of high frequencies. Also, the audience sits in the "reverberant sound field," which is characteristically weaker in high frequencies than the close-up position where the microphones are placed.

In addition, the higher harmonics of the strings and some woodwinds (which radiate upward over the heads of the ground-level audience) are picked up by the elevated microphones. Some high-frequency rolloff (a treble cut) may therefore be necessary to restore the ideal-seat spectral balance. This rolloff can be achieved by (1) selecting microphones with this characteristic, (2) electronically attenuating the highs during recording or playback, or (3) using loudspeakers that roll off in the high frequencies. If the recording engineer's monitor loudspeakers have this rolloff, he will probably choose flat-response microphones and will use no equalization. On the other hand, if his monitor system has a flat response, he will tend to choose duller-sounding microphones or will equalize the high frequencies. Since it is most unlikely that a particular listener's speakers and listening room would be acoustically identical to those of a particular recording engineer, it's easy to see how tonal differences among recordings can arise.

Stereo Effect

Let us assume that at this point the tonal balance has been corrected one way or another and the microphones are placed close to the orchestra but high. We can now concentrate on the more subtle differences between the playback and the live performance. For example, the orchestral stage width may be too narrow in reproduction, or the instruments may sound too widely separated. Controlling the stereo "spread" is a matter of angling and spacing the microphones and of choosing their polar patterns (their response to sounds arriving from different directions) to achieve the proper reproduced stage width, which typically spreads from speaker to speaker. Thus, individual records can vary widely in the amount of stereo separation they display, depending on the skill and taste of the recording engineer.

During stereo reproduction, a sonic "image" of each instrument is perceived between the loudspeakers (re member that it is essential that the listener be equidistant from the speakers when evaluating stereo imaging).

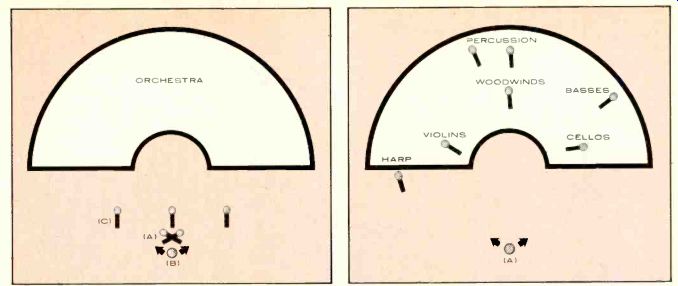

Sometimes these images are sharp and well defined; at other times they are vague and diffuse. Image definition varies greatly with the microphone arrangement used (see Figure 2). Typically, a pair of closely spaced directional microphones aimed in different directions (a, b) provides sharper imaging than microphones spaced farther apart (c). Widely spaced micro phones, however, can sometimes convey a sense of acoustic space surrounding the performers and the listener that closely spaced microphones cannot.

Spatial Reproduction

Even with an acceptable stereo image achieved, there remain several significant differences between live and recorded sound. One thing we discover (or rediscover) right away is that the reproduced reverberation of the concert hall comes only from the front and that it is spread out between the two speakers. To restore the effect of sonic envelopment that live listening gives, ambiance needs to be added to the sides and rear of the listening room. This can be done in several ways, all of which have a slightly different sonic effect.

The home listener can (1) use multi- or omnidirectional speakers to stimulate listening-room reflections, frequently at the expense of some image sharpness; (2) use an ambiance synthesizer or time-delay system with additional speakers placed to the sides and rear; or (3) use an "image-enhancement" de vice to electronically manipulate the acoustic signals arriving at the ears. A recording engineer, on the other hand, can either ( 1 ) record in quad or some other four-microphone ambiance-recovery system, or (2) record with a dummy head placed in the original ideal seat for playback through an electronic "binaural-to-stereo" converter.

Listening-room Adjustments

At this point our playback is finally starting to sound reasonably realistic.

However, in spite of all our efforts, we still aren't quite there. We know, even with our eyes closed, that we are listening in a small room rather than in a concert hall. Somehow the echoes that acoustically define the listening room to our hearing system must be eliminated or masked. Possible solutions include using large amounts of acoustic damping or absorptive panels (there will be a corresponding rise in the amplifier power required), electronic processing of the signals, or highly directional speakers. Elimination of listening-room effects is a problem that still requires a good deal of research.

So far, in our attempt to discover why different records of the same piece of music sound different and not like a live performance, we've covered primarily microphone placement. The choices of microphone distance, height, spacing, and angles all have a great influence on the recorded sound ultimately obtained.

But there is one important variable still to be covered: how many microphones should we use? Let's say that we've found positions for microphones that yield a good direct-to-reverberant ratio, a good frequency balance, and a good stereo image. Beyond this, it's also very important that the orchestra's various instrumental sections be reproduced with the proper relative loudness or balance.

This balance is dictated first by the composer through his notation of dynamics in the score. It is the task of the conductor and musicians to follow sometimes to modify-the written dynamics so as to produce the desired balance in the audience area.

If the ensemble's balances are perfect and the acoustics are excellent, a simple two- or three-microphone pick up (the so-called "purist" approach) can yield a sonically stunning recording. But suppose the orchestra is dispersed on a wide and shallow stage. Instruments close to centrally placed microphones are picked up much louder than more distant instruments at the sides, with the result that the outer edges of the orchestra sound too soft and distant compared with the center.

The orchestral balances as "heard" by the microphones are not the same as those heard by a listener seated further back in the hall. So we must add "accent" microphones close to the far-left and far-right sections, and their signals will be mixed with those from the main microphones. In addition, other closely placed microphones may help to bring out an individual instrumental section or a soloist who would otherwise be "buried" in the recording.

This process can be extended so that every section, or sometimes every instrument, is covered with its own micro phone, possibly even in the absence of a set of main microphones with which these "accents" can be blended. This is known as the close-in multi-microphone technique. With this technique the musical balances are more the responsibility of the recording engineer and producer than of the conductor and players. If the signal from each micro phone is recorded on a separate track of a multitrack tape recorder, the individual tracks can then be mixed down after the session; the conductor can be (or should be) consulted for proper balances. If the signals are not recorded on a multitrack machine, the mixdown is "live" and the balances are almost to tally up to the recording engineer and producer.

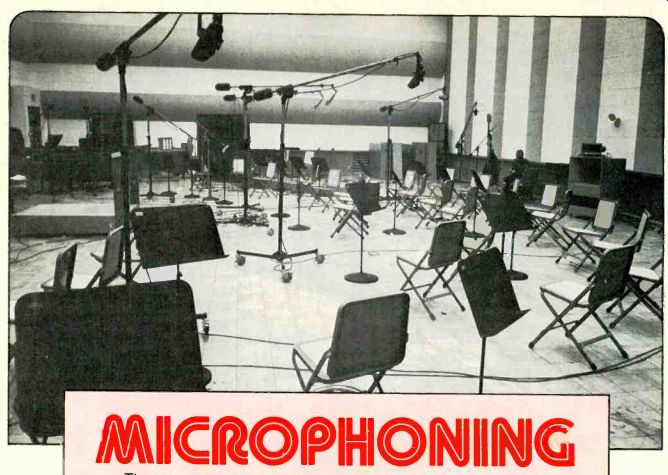

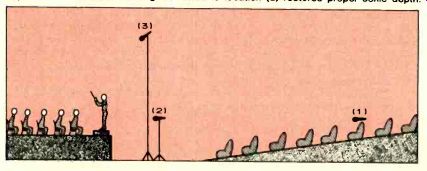

-----Figure 1. Recording from location (1), the "ideal seat" for

live listening, would yield an over-reverberant, blurred result. Location

(2) gives a clearer recording but distorts the depth of the ensemble. Raising

the mikes to location (3) restores proper sonic depth.

---- Figure 2. Basic purist recording setups include: closely spaced cardioid

microphones (A), "coincident" figure-8 microphones (B. Blumlein

system), and widely spaced omnidirectional microphones (C).

Figure 3. A multi-microphone session frequently has separate accent mikes for every orchestral section. A purist setup (A) is often used also to record hall ambiance and/or the orchestra's overall blend.

Purist vs. Multi-microphone

Purist and multi-microphone techniques can have very different effects on the sound ultimately heard in a re cording. Purist techniques using only two or three microphones placed several feet in front of the ensemble (see Figure 2 and Figure I, locations 2 and 3) capture the overall blend, the orchestra's balance being determined mainly by the composer, the performers, and the conductor. In contrast, the multi-microphone method adds "accent" or "sweetening" mikes to those instruments or sections that the record producer thinks need reinforcement to be heard in proportion to the rest of the orchestra (see Figure 3). In this way an acceptable balance can often be achieved faster (and therefore at lower cost) and with less dependence on the arrangement of the musicians and the choice of recording hall than with the purist technique.

With the purist approach, the auditory perspective depends on the micro phone-to-ensemble distance. Instruments close to the mikes sound close and those far from the mikes sound distant, so a sense of depth is immediately captured. The multimicrophone technique often places a microphone close to each section, and the sense of correct sonic distance will often be lost unless reverberation (natural or artificial) is mixed in proper amounts with the signal from each microphone.

A purist technique can (or should) translate the position of each instrument into a corresponding sound-image location between the reproducing speakers. With multimicrophone methods, the image location is controlled by "pan pots," electronic controls that di vide the signal from each microphone between the two stereo channels in varying amounts, depending on the de sired location of the image.

Purist recordings usually sound more natural and realistic than multimicrophone recordings. Simple techniques tend to preserve the musicians' balances, dynamics, timbre, attack, position, ensemble, depth, and relation to the hall acoustics. Reverberation is usually reproduced at a natural level and is spread out evenly between the speakers. Nonetheless, the sonic superiority of the purist approach can work against the music if the balance be tween the musicians is poor or if the re cording hall's ambiance is too dry, muddy, or tonally colored. The result in these cases would be a very faithful re cording of a bad performance in a bad hall. The typical home listener, not having heard the original performance, doesn't know that the recording is both realistic and accurate, but he does know that it sounds bad! Ideally, when making a purist recording, extra time (and perhaps extra funds as well) should be allotted to obtaining a suitable hall for the music and to adjusting the musicians' dynamics and positions on stage for a proper sonic blend. The payoff can be spectacular.

The additional control that a multimicrophone technique affords can be a boon, but it can also be abused, producing a distinctly artificial sound quality. The definition and depth of the stereo image are often degraded, instrumental sections sound isolated in their own acoustic spaces, and disturbing phase-cancellation effects can arise.

Most important, using multiple microphones can degrade the perceived musicality of the performance. For ex ample, in a poorly done multimike re cording the final balances may not be what was originally intended either by the composer or the performers. Instruments may "jump" unnaturally out of the orchestra for a solo passage only to fall back into the ensemble afterwards.

Reverberation surrounding each instrument, which had originally blended the instruments' attack on the notes and/or filled the spaces between notes, may be missing. The perceived unanimity of rhythmic attack can be altered and made sloppy by the close microphone placement, and balances within a group or section may be hidden. In sum, a mishandled multimicrophone approach can negatively affect our perception of the music and thus hamper musical communication.

Live vs. Recorded

A live concert is often a profoundly affecting sonic experience, and in re cording it the engineers and producer may, out of respect for the music, choose to maintain a low profile, to commit the original sound to tape with as little technical intrusion as possible.

At the other extreme, a recording can be viewed (and heard) as an end in it self-a creation rather than a re-creation-in which sounds have been tailored (also out of respect for the music) to enrich the home listening experience. Microphone techniques can be applied to attain either goal.

Purist methods generally offer the most realistic sound, but it is a simple fact that some ensembles and pieces of music cannot be recorded successfully with just two or three microphones.

And though multimike techniques offer a way of obtaining a well-balanced re cording in difficult situations, they can, if abused, produce unnatural and un musical results. Ultimately, the sound quality depends on the musicality and technical skill of recording engineers and producers.

---Bruce Bartlett is a senior development engineer, specializing in microphones in Shure Bros.' electroacoustical department.

Also see:

THE CASE FOR MINIMAL MIKING: The "back to realism" movement is invading the nation's recording studios.

CLASSICAL MUSIC (reviews)

Source: Stereo Review (USA magazine)