Conversations

with Peter Baxandall; Part 1--A visit with the designer of those fed

back tone controls.

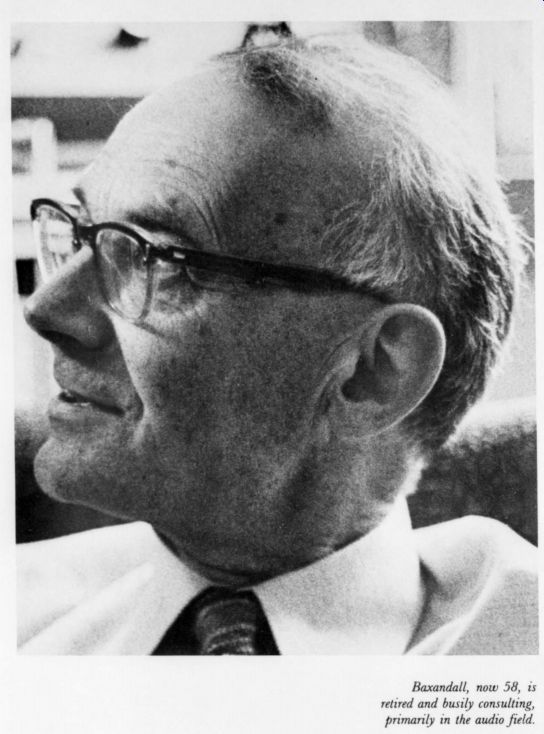

Baxandall, now 58, is retired and busily consulting, primarily in the audio field.

TAA: When do you reckon your interest in audio began?

PJB: Well I have a photograph taken in 1926 when I was five years old, and I can still remember being extremely fascinated by this wireless set which was then quite a new thing to me. I spent hours glued to it. I suppose that's a beginning of interest.

TAA: You experienced the electronic age before you could read and write, then?

PJB: Well, yes, I suppose that could be said. I had an early fascination with electric motors and things.

TAA: Dud you get into model railways at all?

PJB: Yes, I had a Hornby Gauge O electric model railway which used to get put out both indoors and in the garden. The boy who lived next door at that time was also interested in model railways, and we used to connect our systems together through a hole that went under the fence. The first serious interest in anything that one could consider to be hi fi occurred about 1934 when I went to stay in Cardiff with my brother, who is a good deal older than I am. He had a great friend named Hugh Ryan who had been a keen amateur radio enthusiast just after the First World War. This chap was very musical and early took an interest in what one might call hi-fi's beginnings.

When my brother married in 1933 Ryan made for him what I used to describe as a local station, high quality receiver. The loudspeaker was a large baffle box with a 10" BTH RK loudspeaker in it. This sounded far better than the sort of radio set I was us ed to hearing, and I became fascinated with it. I was then beginning to be intrigued with radio principles.

TAA: At what age was this?

PJB: I'd be 13 or so at that time, and I was beginning to make simple little valve sets at home, so I look ed up to Hugh Ryan as being the great authority on these things, who'd made something incomparably better than anything I could ever envisage myself making. By 1937, however, I had made a device which was intended to be a high quality local station receiver. It was exceedingly crude, of course, but it had resistance/capacitance coupling which I had read was a superior thing to use instead of the transformers used in most sets at the time, and it had a triode output valve. It was an attempt to do one or two of the things that I'd read in the elementary books. It was just a reactive leaky grid detector and two RC coupled triode stages, and gave about half a watt output. Unlike most sets at the time--but like my brother's--it had tuning for two stations and gramophone. It operated off a battery eliminator with extra smoothing, so there was no hum. Well, original ly it had a moving iron loudspeaker, but it wasn't long before I acquired moving coil type. At one time I was rather proud of it-it's a museum exhibit by now!

TAA: But that's how you began.

PJB: Well, yes, that's the way one learns, isn't it? That was 1937 when I was still at school.

TAA: School was where?

PJB: King's College School, Wimbledon. By 1939 I had made all arrangements to go to City and Guilds College in South Kensington, London, to do a degree in communications engineering-I was pretty sure I wanted to go in for radio or something of that kind-but that went wrong, unfortunately, because this was the summer vacation during which war was declared, and the City and Guilds College hadn't got around in time to building sufficient air-raid shelter accommodation. At that stage everybody thought London was going to get bombed intensively right from the beginning. It didn't happen but City and Guilds decided to close down their first year engineering course. This happened two or three weeks before the beginning, so I was suddenly in a rather difficult position. My father had died about a year before; my mother wasn't capable of doing much about problems of this sort, so I talked to one or two people, particularly my brother, and sent off applications to various other possible places.

I fixed up at Cardiff Technical College, really because my brother was, at that time, head of the art department in the National Museum of Wales at Car diff, and he knew some of the staff at the college. As technical colleges went, Cardiff was rather a superior one. But they didn't do a communications course, so I took a course in electrical power engineering-I just had to accept that. I didn't really expect to be allowed to go straight through: I thought I would probably have my studies terminated after a year and get put in the forces. I feel I was one of the very fortunate peo ple, I was allowed to go through and I got my B.Sc. Engineering degree there in 1942.

I lived in a little village called Rhiwbina about four miles from Cardiff, and though I cycled to college most of the time, occasionally in wet weather I'd go in the bus and sometimes sat next to Mr. Vernon, head of the college physics department . As we talked he found out I was fascinated with radio and had made myself a short-wave transmitter before the war, you know, which meant I had an amateur radio license.

He had undertaken to run a war-time radio and radar training course for service personnel. One of his problems was finding the staff to teach the course and also people who could quickly build up various bits of demonstration apparatus. He said to me, 'You know, it looks to me as though you ought to be able to help me quite effectively with your hobby interest in the field."" So while a student I used to go during vacations and help them a bit making bridge circuits, model aerials, an oscillator or two, for use in this training course. So when I got my degree in 1942 I was expecting I would be called into one of the forces, but Vernon managed to get me exempted from that and I became a temporary instructor in this Fleet Air Arm wartime radio training scheme. I stayed there until 1944 when it was closed down. I came straight from there to what is now called the Royal Signals and Radar Establishment (R.S.R.E.) in Malvern, though it was called T.R.E. at the time, for Telecommunications Research Establishment. That was typical wartime terminology intended to mislead Hitler a bit, you see, because it never had anything to do with telecommunications actually, it was a radar establishment from the beginning.

I came to T.R.E. as a result of a friendship. One of my school friends, a chap named Grinsted, had invited me 'round to their house quite a lot when I was at school. He was keen on making things, especially electric clocks. We were great friends, and his father was a senior man in the Air Ministry. When I wrote to say the course I'd been teaching was closing, he said, ''Ah, you might be just the sort of chap they're looking for at T.R.E., our radar establishment in Malvern.'' I came here in 1944, and I've been here ever since, retiring in 1971, to set up as an electro acoustical consultant.

TAA: So your professional work was in radar to begin with, but T.R.E. didn't work exclusively with radar after the war, did they?

PJB: No, that's right. When I first came to T.R.E., I was put to work on wave guide techniques, K-band which was about 1.5 centimeters wavelength. It's a funny thing, I've gone down in frequency ever since-because, well, I started on K-band, I then did quite a lot of work on X-band, a slightly lower frequency, and though I was nominally in a microwave division at that time, I never felt I had quite the right sort of natural attributes to be really fully effective in the microwave field. It seems to me it's rather a mathematician's area beyond a certain point, and though I quite like mathematics, I have no natural aptitude for it beyond the elementary level. But I've always been fascinated by what one might call the circuitry field, and I tended while in this microwave division to gravitate towards stabilized power supplies for feeding klystrons, and thermistor bridge circuits. I think it became evident to the people I was with that I had a natural bias toward the circuit field.

During the war, T.R.E. was an amazing establishment. It gathered together the absolute cream of the country's brains, and not only of our country, either-yours as well. The British branch of the M.L.T. Radiation Laboratory was there too. Well, all this tended to get disbanded fairly soon after the end of the war, and in 1946 I started working in the circuits research division run by Professor F.C. Williams. At the time he was looked upon as the leading light in the field of special circuit developments for radar'. He was one of the authors of the 30-volume M.I.T. series published immediately after the war. Volume 19 on radar circuit work, was authored in part by him.

My assignment was a great piece of good fortune.

He was a very inspired individual, and though I was only actually working in the division with him for less than a year, he gathered and trained a number of bright, effective and very creative people in the circuit field. Some of those stayed on after he left at the end of 1946 to become Professor of Electrical Engineering at Manchester University, where he and his colleagues built the first really effective electronic digital computer, which had "Williams tube storage,'' later adopted by IBM in some of their early computers.

Subsequently I worked for S.W. Noble, who's still around but retired, and lives not far away. I learned a great deal from him about the right sort of basic philosophy for looking at circuit problems. This group did not look sideways and try to find some existing recipe to solve some problem: we looked at the fundamentals of the problem and did not worry too much about what other people had done.

I still had a great interest in audio. And in an establishment of this sort, of course, there are amateur theatrical activities and gramophone recitals and things like that going on. So I got to know a few other audio enthusiasts, particularly two people, Desmond Roe and Alec Tutchings. Tutchings had been chief engineer of a Glasgow public address firm, which was quite a go-ahead set-up and a leader in the field. He knew a lot about the practical points of making ribbon microphones and such, so I learnt a lot of valuable practical hints and tips from Alec Tutchings.

Desmond Roe had a flair for finding the easiest and quickest way for home-making things. There wasn't very much on in the way of entertainment, you know, we had to make our own at that time. I used to go back to R.R.E a lot in the evening and make moving coil pickups and microphones and various things.

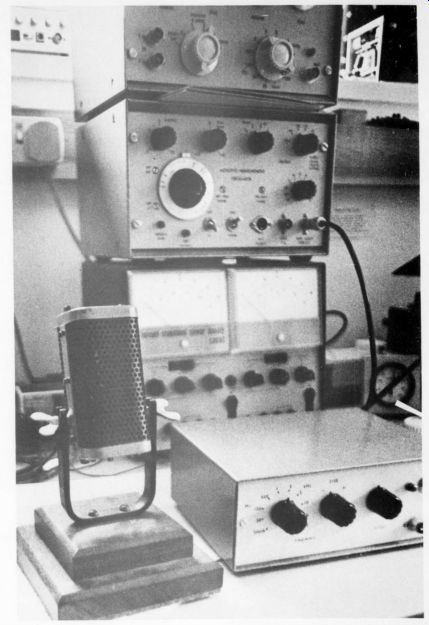

That mike was used for a lot of events in the evenings at R.R.E. It has been at the sending end of a B.B.C. transmission, actually.

TAA: It's amazing how good the things we can make can be. I get letters from readers often full of surprise at how good what they make can sound-and they always seem to expect something somebody manufactures is likely to be better. But that isn't always true…

PJB: No, it's not always true--sometimes it is. I think what I can best claim for that microphone is that it has proved to be very reliable, because I never serviced it and it is still working I suppose about as well as it ever did. But it's not as good as today's best devices, not by any means. I tried making a piano recording on it recently and it's not really up to the best standards. But at the time it was very acceptable.

TAA: And you had a lot of fun making it.

PJB: Oh, I had a lot of fun making it, that's right. I think the total material cost for that would have been about ten shillings. [About $1.]

TAA: At that time there wasn't much of known quality audio circuitry was there? Had D.T.N. Williamson appeared as yet?

PJB: No, but fortunately for me I got to know C.G. Mayo at T.R.E. at about that time. He had been a member of the B.B.C. Research Department since before the war. Mayo was an extremely inventive individual, a very sound chap, rather mathematically inclined. He believed if you needed some circuit to do a certain job, you should be able to calculate it and design it, and that when you made it, apart from maybe the possibility of one or two rather silly things like parasitic oscillation, by and large it should be able to do the job properly without having to be messed about with empirically.

Prior to about 1935 Mayo had been with British Thompson Houston's instrument transformer design department. As a result he acquired a lot of expertise in transformer principles, mumetal characteristics, leakage inductance, stray capacitance and all the problems of the transformer designer. He'd been very interested in radio, more in a private way, but about 1935 he joined the B.B.C. Research Department. He arrived as a sort of lively young man who looked around at the various things that were going on and I think had a major effect on the work in the audio field, particularly.

The B.B.C. had outside broadcast amplifiers in great wooden cabinets that were run off ac cumulators, and had lots of triodes and an anode cur rent meter for each of them-enormous great bulky equipment, thoroughly well made, but very uninspired really. Now Mayo had the great sense to appreciate almost straightaway that the fairly new notion, as it then was, of negative feedback was an exceedingly significant one and that the B.B.C. ought to be making use of it in everything they did in audio.

They weren't, of course, at the time. The other thing he very much appreciated was the virtues of the high slope television pentode. He recognized it was a very much better amplifying device for audio purposes than were the low gain triodes; a much more sensible, more economical device as well. By 1938 he, with one or two active cooperators, had designed what became known as the BBC OBA-8 equipment-Qutside Broadcast Amplifier. The OBA-8 was mains operated and used feedback and pentodes to put audio onto a telephone line at the outside broadcast site, using rib bon microphones-also fairly new to the B.B.C. at the time. It had a peak program meter.

What previous designs had needed four or five triodes to do, Mayo did with two pentodes. And negative feedback was used to control the output impedances and lower the distortion. That equipment, which was made in fairly large numbers, had a performance which is still good by present-day standards.

I think it marked a turning point in the B.B.C.'s attitudes toward audio. Also, by 1939--and Mayo was very much involved--the B.B.C. Research Department had produced a very high quality 10 or 15 watt loudspeaker amplifier using high slope pentodes and lots of negative feedback. That amplifier had a performance which, if it was used now with the best pro gram material and modern loudspeakers, would leave little to be desired, except perhaps, with regard to available power! In that respect it was almost unique because the average audio amplifier in those days was a pretty rough device. Mayo was very careful and logical about things, you know-he realized that the hum levels had to be right down, and that proper attention should be given to signal-to-noise ratio pro blems in early stages. The gain control arrangements should be such that when you turned the gain well down for loud program sources you shouldn't com promise the noise performance or get distortion occur ring in early stages. He really properly and logically understood what the fundamental design problems were, and his expertise in transformer design served him in good stead when it came to putting negative feedback on over output transformers.

I went to see him in my very early days at T.R.E., and I can well remember several quite long sessions in his office-he was much older than I was, you see, and he was jolly good to me. He realized I was quite interested and keen on audio and he spent hours telling me little hints and tips he'd learned at the B.B.C., and he said, ''Look, you should forget all this triode business, much better idea to use pentodes, and plenty of negative feedback. There's no reason why you shouldn't put 40dB of negative feedback over a transformer if you understand what you're doing." And he was very keen on the technique in audio loudspeaker amplifiers of feeding back from a tertiary winding rather than from the output secondary win ding, because if you do the right thing in feeding back from a tertiary winding, you can ensure that the feed back loop remains stable no matter what sort of awkward load you may put on the output winding.

The reason I originally went to see him was that I wanted to make a good audio amplifier for general use and gramophone concerts. I asked if he would give me a few hints and tips. He did and I built myself an amplifier largely based on this pre-war B.B.C. design. I did my own transformer design, us ed 6L6s, generally altered it a bit and published it in Wireless World in January, 1948. It came a bit after the D.T.N. Williamson amplifier, and the two became, one might say, competitors to some extent. I think from the quality point of view, they were very comparable in performance. I always believed that the fact that mine would not oscillate, whatever sort of load you put on the output, was a strong point in its favor. This was not true of the Williamson. And because mine used output tetrodes it required only 300 volts supply which economized a bit on the power supply arrangements. The Williamson had 400 volts, I think.

TAA: Did your Wireless World design have a tertian winding?

PJB: Indeed it did, it was really based on what I'd learnt from Mayo and he was suitably acknowledged at the end of the article. I had the prototype in use for years-until 1960 actually. I got it down about a year ago when the B.B.C. did an experimental quadraphonic broadcast. It matched perfectly nicely with my more recent Quad solid state amplifiers. I really couldn't tell any difference in the sound.

But of course the Williamson design caught on. It is interesting the way some things catch on and others don't. It obviously appeared at about the right time During the war a lot of people had begun to get fascinated with the idea of good quality sound reproduction. I think most people then still believed there was nothing to beat triodes if you wanted the best quality.

TAA: There are still some people who like triodes, of course

PJB: It's absolute nonsense, but it was a strongly held belief and the Williamson amplifier had them, so that gave it a good point. And indeed the fact that it was rather large and bulky and had plenty of impressive-looking components I think probably influenced some people in its favor.

TAA: Where did you go from there? The tone control, perhaps.

PJB: Yes, I said I'd made that so-called local station high quality receiver in 1937. Now while I was a student I made something doing the same job, but rather better. This was also a local-station switch tuned medium and long-wave receiver and gramophone amplifier, but I'd learnt a bit by then and it had a single-ended pentode output giving about 3%, watts, with plenty of negative feedback from the transformer secondary, for I hadn't learnt about tertiary windings yet.

The receiver had bass and treble controls giving both lift and cut. It was done with switches and was passive. While at Cardiff I read Wireless World which carried a series of articles by Paul G.A.H. Voigt.

He was a splendid chap. One thing which encouraged my schoolboy interest in sound was membership of the New Malden Radio Society near Wimbledon. They invited various people to lecture and Voigt was among them. He demonstrated his corner horn loudspeaker. I heard that evening a standard of music reproduction I'd never heard before, and that was certainly a quite significant event for me. Well, Voigt wrote a series of Wireless World articles with the title, "Getting the Best from Records." One of them? taught me something I didn't appreciate at the time, all about a thing called a recording characteristic. He gave an actual curve he believed represented the approximate recording characteristic then in use, although no very accurate standard then existed. If you did the thing right you ought to equalize gramophone pickups to take the characteristic into account.

He gave a circuit for doing this, and I tried it. It improved the reproduction I got from an ordinary gramophone pickup quite a lot. He also included a circuit for a bass and treble control with pots which gave both cut and lift at the bass and the treble end.

This was 1940. I have never really been able to understand why Voigt's circuit appeared to make absolutely no impact whatever in the audio field. It was quite a good circuit.

TAA: Maybe the war diverted it?

PJB: I think it emphasizes that all these things have to happen at the right time and in the right circumstances. Well, when I came to T.R.E., and into the circuits division, in which we lived in an atmosphere of negative feedback, it seemed worthwhile to rethink some of these tone control ideas. Tone control circuits provided a very good exercise in using the "J" notation and other things one got taught in college about elementary AC circuits.

By 1950 I had produced a negative feedback tone control, almost like the one published in Wireless World. 1 belonged to the British Sound Recording Association which was a splendid organization, really, which operated very enthusiastically during the immediate post-war years. The membership was a mix ture of enthusiastic amateurs and people from industry. They held regular meetings in London where I first met Peter Walker, Cecil Watts, Harry Leak and others whose names became quite well-known in audio. The B.S.R.A. held what were largely trade exhibitions annually in London's Waldorf Hotel. These were pleasantly small scale, the number of people interested in hi-fi was pretty small by present-day standards. All this could be put into the hotel's ballroom and a few bedrooms and wasn't overcrowded. Most of the participants were enthusiasts and one got an opportunity to talk to people in the industry quite a lot.

They sponsored an exhibition of amateur-made equipment where a quite large room was just full of home-made tape recorders, disc-playing equipment, receivers, amplifiers, everything. I found this an absolutely fascinating set-up. I used to put odd things in, my microphone went in one year, and later the original version of what became known as the Baxandall tone control.

At the time I didn't appreciate the full commercial significance of that circuit. It was just another way of doing what Voigt had done; a bit better, yes, it had the convenience of unity gain with the two control knobs set flat, so you could build it into existing equipment without disturbing the planning of the stages too much, which was quite nice. Well, I put this in the exhibition and to my very great surprise I got the annual Wireless World prize, that year a £10 wristwatch. And apart from a manufacturer supplying to me six free center-tapped pots, that is the only money I ever actually made out of the tone control.

How many millions of them have been made since, goodness knows.

Harry Leak was particularly pleased with my circuit and thought it something really worthwhile. In deed it was just what he wanted for the next Leak control unit-and it appeared in their next model.

Wireless World's editor asked for an article on the circuit and I took off a week of leave from T.R.E. and really got down to writing. From there the thing snowballed, rather to my surprise.

----------- Baxandall's handmade microphone has seen service at the sending end of B.B.C. broadcasts. At right on the bench is the simpler oscillator to supply fixed frequencies for distortion tests.

The middle unit of the stacked instruments behind the mike is the diode bridge oscillator. (See text.)

---------

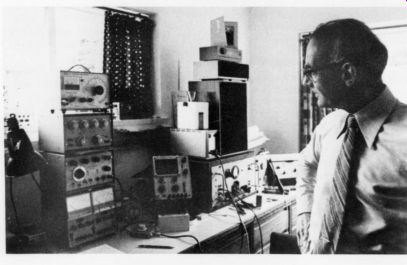

Baxandall keeps a tidy electronics workbench, with test equipment in the foreground, mostly handmade, with audio and shortwave gear further down the bench.

TAA: As a matter of fact your name has become almost synonymous with the feedback tone control, and since then no self-respecting design is ever anything but a Baxandall.

PJB: That's right. Though in Wireless World a few months back it was referred to in a very grumpy letter as ''the usual Baxandall horror!'' The chap was in a real bind about everything. I have often wondered, of course, what would have happened if I had put a pa tent application in on that at the right time. Two things could have happened. One would have been that some commercial organization would have said

We must find a way "round this'' and would have designed something they felt was outside the patent and it would never have caught on. But of course if I had got sixpence or something on each one sold, I would obviously be very wealthy by now.

TAA: You might have had the sort of problems Edwin Armstrong had with FM.

PJB: Oh yes, poor old Armstrong. It's a pity, really, because he never won his infringement suits although his wife did, but only after he'd committed suicide.

Yes, he took it all too seriously, I'm afraid. An awful pity.

TAA: But he did have something, and it is true the big companies do make it a regular practice to bypass patents, if they can, even if they must develop an inferior circuit.

PJB: Oh yes, well, RCA actually made FM receivers without limiters in, even. My admiration for Armstrong as a pioneer in the radio and audio field is enormous. An amazing man, really. When you consider the date at which he was putting out high quality FM transmissions on about 100MHz--1934 or 1935--well he was absolutely years and years ahead of everybody else in all sorts of ways. And of course not only FM, he has the leading patent on the superheterodyne receiver, hasn't he, and a lot in the superregenerative receiver field as well. Indeed he could stake a fair claim, I think, to the idea of making a tuned circuit oscillate with a valve in earlier years.

People talk a great deal nowadays about Blumlein as being a major audio pioneer, and certainly he was, but I think Armstrong was at least an equal pioneer in that broad field.

TAA: Armstrong's been a sort of underground hero rather than an acknowledged one, I think.

PJB: Well, that tends to happen. I think the same applies to Blumlein. In very recent years his name is being brought to the fore a bit more but. . .

TAA: But when one looks for material about him or by him there's very little.

PJB: He wrote very little himself. One has to bear in mind he was killed at the age of 38, having achieved a perfectly fantastic amount by that age®'*.

TAA: Isn't he supposed to have averaged one patent every six weeks or so?

PJB: That's right. Of course, in all fairness, not all of his 130 or so patents were very significant ones, but some of them are very significant indeed. One of them, I feel, was a truly splendid notion: the transformer ratio arm bridge. It is still a source of amazement to me that you find quite recent books coming out, where people describe in detail the Max well bridge and the Owen bridge and the Shering bridge and others, but they won't mention Blumlein's transformer ratio arm bridge which beats the lot. It has every advantage for most purposes: equal sensitivity for measuring from 1000M-ohms down to milliohms, a tiny fraction of a picofarad to a thousand microFarads-equally easy to use, equal sensitivity, freedom from errors due to stray capacitances in the wrong place, reliance only on two basic standards rather than on a whole set for all the different ranges.

You either get the transformer with the right numbers of turns on when it's made or you don't, and if you do, the thing will be just as accurate 40 years later as now. An absolutely sweeping, splendid scheme in the bridge field, but still often not mentioned in books which is absurd®.

Then about 1931, Blumlein in this country and some time later Bell Labs in the States were doing lots of work on stereo. Blumlein developed the 45/45 disc recording/playback system-I mean, that patent of his is amazing, really, the detailed thoughts that he had. And he was also the main innovator behind most of the television circuits that went into the Alexandra Palace TV station of 1936. He was killed in a flying accident when working on radar at T.R.E. I never met him-it happened before I arrived. Professor Williams said that had he not been closely associated with Blumlein, he didn't think he'd have ever fully, so to speak ''taken off' as far as creative circuit work goes. I suppose I could say that indirectly I owe a good deal to Blumlein for the good fortune I've had in circuit background.

TAA: Very little money is being put into pure research on audio in the States--it's nearly all going into product development work.

PJB: I think the major contributor to fundamental audio research in my country has been the BBC Research Department, but there are strong pressures nowadays to subdue the audio work in favor of work on color TV, satellite broadcasting, etc.

TAA: Since the tone control you've published your article about the small elliptical speaker, of course. [See TAA 2,3/1970]

PJB: The background to that is somewhat amusing.

It arose in a rather peculiar way. At R.S.R.E. I sometimes used to get dragged into recording conferences etc. I designed an installation for one of the projection rooms in the hall and one of the associated problems was that we wanted a reasonably good, fair ly cheap loudspeaker for putting on the wall. Without giving a great deal of thought to it, I had some boxes made up in our engineering unit, and put 9x5" elliptical Elac speaker units in these. And they were straightaway quite adequate for that purpose.

I was quite surprised how good they sounded when I brought them home and put some music signal into them. Well, for one reason or another, this brought me 'round to thinking it might be worth tidying up this design a bit and giving some more precise thought to getting the equalization and the low frequency damping right. That was really what led to this design which I used a bit in one or two lectures, not as main speakers but just as a recent experiment I'd been doing that might interest some people.

When I finally tied it up and got the equalizer properly designed, it exceeded initial expectations. At that stage somebody suggested it might be worth writing up for Wireless World. It was never conceived of as an ideal state of the art loudspeaker. It was a low-cost design to avoid any major pitfalls and sound ed fairly pleasant.

TAA: But, you know, it is really superior for all that.

PJB: Well, I think it is free from any sort of major fault kit has its limitations.

TAA: Was there any reason why you chose the elliptical driver?

PJB: Well, the audio man at EMI, Dr. G. F. Dutton, was of the belief that the elliptical diaphragm was free from some of the worst hangover effects that one gets in circular diaphragms, or at least that they were distributed a bit more evenly in frequency. I think the influence for the Elac elliptical unit was that Neve, now marketing mixer desks, marketed a speaker with an Elac elliptical driver, which I borrowed. It sounded better than most others I'd heard so I naturally chose it for my design.

TAA: If you had twelve months clear time for an audio project of your choice, what would it be? PJB: One thing fascinates me to which I haven't had time to devote as much thought and experiment as I would like, and that is headphone reproduction. I would enjoy that. Nowadays there's a great deal of interest in quadraphonic, or surround sound techniques. It would seem in principle that one ought not to need these techniques for totally natural sound reproduction, if one uses headphones with an artificial head at the recording end. Now, I say ''it would seem in principle,'' and we all know that things don't work out just like that. The fascinating thing about head phone reproduction is that even though you may take enormous care with the characteristic of the microphone capsules used on an artificial head, and over the design of the headphones and everything that goes between, you never in practice seem to get the proper illusion that the sound source-the orchestra, the instruments, the choir, whatever it is-is out in front of you.

I'm not convinced it isn't possible to get 'round this; I believe there's room for a great deal of work there. I know, of course, that some work is going on, and I'm probably ignorant of some of it. I'm sure that psychological factors as well as quantitative scientific ones are very much involved. I'm certain the fact that you can't see the orchestra in front of you makes it more difficult for imagining where the sound comes from. It's well known, I think, that the listener has a tendency under these circumstances to perceive the sound as being behind him, and this is a great pity. If one could do something to alter the listener's illusion, I think you'd make the musical effect much more satisfying.

Some people are much more put off by the fact that the sound doesn't seem to be in the right place than are others. I quite like headphone reproduction myself but some people find it very tiresome. I believe it might help to make an arrangement so that when you turned your head you slightly altered, the signals fed into your ear-pieces in a way which would tie up with what happens when you do this in a natural circumstance.

TAA: Not a pot tied to the ceiling?

PJB: Well, a pot tied to the ceiling obviously is the first crude thought, but it shouldn't be all that difficult to do it more elegantly than that, a sort of inertial control arrangement so that when you move your head some little mass can stay behind. I'm sure that in one way or another there are options for doing something there. But I think there are also other possibilities because, in natural circumstances, the first sound-wave that reaches one's ears from the live sound source will be propagated in a direction away from the source, and I think it's probably true that each ear's earlobes are slightly sensitive to the direction of the sound. One's first thought is that this not the case, the only thing that the ear can be sensitive to is just the pressure acting in the ear-hole. I think there's probably more to it than that, and I think you've got a little reflection structure and probably it is aware of the direction of a sound-wave moving past the ear. But I would think that by making headphones perhaps with two elements on each side, by using either delay lines or some of the more recent digital delay techniques, it might be possible to gain at each ear the sense that the sound is coming from the front to the back part of each ear rather than the other way 'round. Well, maybe that or the first technique I mentioned, or a combination of the two, or perhaps something different again, would be capable of dispelling this unfortunate psychological tendency to feel the sound is behind you.

TAA: What area of home reproduction audio do you consider needs the most work?

PJB: Two rather different thoughts come to mind.

The first is obviously what further sort of new ideas and development should occur in the field. But the second is that it seems to me, as far as the majority of people are concerned, the primary need is to improve the sound reproduction ordinarily achieved in more average people's homes. I mean, we all know very well that when a good firm tries hard and puts on a demonstration at an audio fair, they produce a very impressive standard of reproduction. But sadly, when one goes around to some non-technical person's home and a record is put on, it's often all full of clicks and distorting dreadfully. The average standards are often deplorably low. I sometimes feel that if more was done commercially to encourage the design of simple, very robust, soundly designed equipment, a lot of people would benefit more than from the present trend towards more gimmicks, touch-button controls and increased complexity.

TAA: Higher quality, simpler equipment?

PJB: That about sums it up.

TAA: Produced in great quantity and with high reliability?

PJB: With high reliability. Many musically interested people, schoolmasters who like to tape record, and so on, would be more likely to get good results with simpler equipment. It's a funny thing: if you examine the tape recorder the B.B.C. bring to record a local concert it is often a Studer which is by the same firm who make the ReVox. The professional unit is much simpler to use than the hi-fi market ReVox. It is very solidly made but with no clever facilities for transferring recordings from one track to the other. Some of these facilities on the ReVox I find extremely perplexing! Not having used one for some time, you suddenly want to do one of these tricks, putting in some echo or something, and you scratch your head like anything trying to make out what switching arrangements to do. The Studer professional machine is an absolutely basic recorder, extremely well made, in which you just plug from one thing to another rather than try and use an extraordinary switching scheme. The simpler version would be much more straightforward for a lot of people. So that is one field where suitable things need to be done.

TAA: Strip down the equipment io the basics.

PJB: It would need a lot of very skillful advertising to persuade people that it is sometimes sensible to spend quite a lot of money on something that has not got this and that gimmick.

To be concluded in the next issue.

Also see: Conversations with Peter Baxandall: Part II Opinion from a distinguished British engineer/audiophile.