THE GOOD AUD DAYS

With justifiable pride and appropriate ruffles and flourishes, this issue celebrates the 40th anniversary of Audio magazine. When this publication was launched in 1947 as Audio Engineering, it was coincident with what is generally regarded as the beginning of the high-fidelity era. Ever since, this journal has faithfully chronicled the spectacular growth and remarkable technical advances in the field of audio.

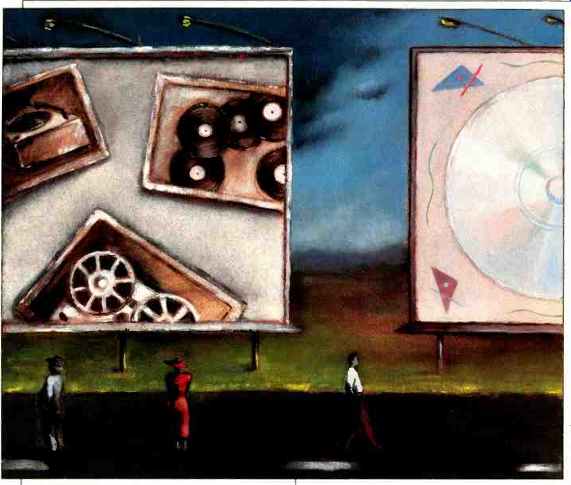

Forty years ago, people in this country were listening to music on 78-rpm records. These fragile discs provided just four minutes of music per side, so the only way to hear long works without leaping to the turntable 15 times an hour was to use cumbersome record changers. These players relentlessly attacked the record grooves with several ounces of stylus tracking force to the accompaniment of great amounts of hissy, scratchy, crackling surface noise. Even the most wide-eyed visionary could not have foreseen that 40 years hence, we would be listening to music from little silvery discs that provide nearly 75 minutes of playing time with no surface noise whatever, discs that are tracked by a beam of light! For the first several years of its existence, this journal was read mostly by audio professionals in the broadcast and motion picture fields. (I myself discovered Audio Engineering in the Georgia Tech library in 1949; soon I was avidly reading the back issues and enjoying the interesting observations of Edward Tatnall Canby!) A few years later, strictly by happenstance, some very zealous audio hobbyists discovered the superior quality of loudspeakers, amplifiers, and other equipment used in broadcasting and motion pictures. Thus the "hi-fi nut" was born, later to be dignified by the appellation "audiophile." Many old-timers rather wistfully re call the early hobbyist days of audio.

There was indeed an aura of excitement, as new advances and developments provided an ever-higher degree of fidelity in the reproduction of music.

There was also an element of camaraderie-somewhat akin to the early days of sports cars, when aficionados would wave to each other on the road.

In the early '50s we had "audio fairs," where manufacturers could demonstrate exciting new products to hordes of eager audiophiles. One fondly remembers that if you owned a Fisher tuner, you could talk about your unit with Avery Fisher himself. Similarly, if you used Bozak loudspeakers, Rudy Bozak was on hand to answer your questions. If you were lucky enough to own McIntosh or Marantz amplifiers, Frank McIntosh and Saul Marantz were always willing to discuss their circuitry.

It is this kind of up-close and personal contact that makes people talk about the "good old days." But it has long since faded from the scene, as have the audio fairs and most consumer shows. With the demise of the Terry Rogers audio shows some years ago, an era ended. It is a shame, really, that today's audiophiles have little opportunity to savor the fun and excitement and new product introductions once provided by these shows. They still exist in foreign climes, most notably in England, where the annual Heathrow/ Penta show is held.

What kind of equipment did we use in the old days? It must be noted that in the early years of Audio, there were no hi-fi salons or dealer stores such as we have today. There was no place you could buy commercially manufactured home loudspeaker systems; there was no AR, no B & W, no Polk, or any other.

It was, of necessity, the do-it-yourself era, so we all built big bass-reflex en closures, lined them with Tuflex or car pet underlay, and used such things as Altec or James B. Lansing 15-inch theater woofers, crossed over at 800 cycles to multi-cellular-horn compression tweeters! If you were really lucky, you were able to get the great Western Electric 713C driver coupled to a 12027 cast-aluminum sectoral horn, which could respond to 15 kHz. Eventually, some new speaker drivers appeared on the market and began to supplant all the old theater equipment.

Not long after that, complete speaker systems started to become available.

A vogue for all sorts of horn-loaded enclosures began. Audio editor C. G. McProud designed an efficient horn system which was constructed by quite a number of audiophiles. A huge, bathtub-like, back-loaded horn was made for the Jensen triaxial loudspeaker. For electrical-engineering students, it was practically a rite of passage to arduously construct their own Klipschorns!

Some of us favored infinite baffles, and in 1954 I decided to build a real blockbuster speaker. Even in those early days I was a firm believer in the value of anti-resonant enclosure construction. I made a huge enclosure with 16 cubic feet of internal volume.

Each enclosure wall was made of two 3/4-inch-thick pieces of plywood with an inch of space between them. In the manner proposed by Gilbert Briggs of Wharfedale, this space was filled with fine, dry sand. The driver complement was two 15-inch Wharfedale woofers, two 8-inch Bozak midrange cones, and an array of eight 2-inch Bozak cone tweeters. Crossovers were at 350 and 3,500 Hz. This behemoth weighed more than 600 pounds; driven by 75 watts of McIntosh power, it put out one helluva sound, with especially clean, non-boomy bass. Brute force indeed, but sand-filled panels were (and still are) a fairly effective anti-resonant construction.

Back in the old days, amplifiers were as controversial a subject as they are today. The 30-watt Brook amplifier using 2A3 tubes was the top choice among devotees of triode design, while the 50-watt McIntosh 50W2 amplifier was the darling of those who fancied the 6L6 beam pentode tube. A little later, Marantz was setting the standards for triode design, while McIntosh still reigned supreme in the higher powered beam pentode camp.

A few years later, there was a lot of interest in building amplifiers from kits.

Heathkit sold a lot of them, but the most prominent name in amplifier kits was David Hafler, whose Acrosound design was very highly regarded for its Ultralinear transformer. Audiophiles were also building Williamson amplifiers, a British design, and for years the Partridge Transformer Co. of England ran an ad in Audio extolling the virtues of using their product in this type of amplifier. When the first transistor amps came onto the market, they were scorned and castigated for the harsh, strident sound they produced. Of course, things are different now, but many vacuum-tube amplifier aficionados still think transistors are the invention of the devil! Oddly enough, until well into the hi-fi era, turntable and tonearm design lagged well behind amplifiers and loudspeakers in terms of technology.

About the best we could do was use a Rek-O-Kut turntable with a hysteresis synchronous motor and a Pickering arm and cartridge. To cut down on the omnipresent turntable rumble, we would employ the "high mass" approach. We would use a 3/4-inch-thick piece of steel boilerplate, cut out mounting holes for the turntable and arm with an acetylene torch, and then mount this massive plate on a very heavy wooden plinth! Later on, we modified the plinth by mounting it on hydraulic dampers. Still later, we abandoned the massive turntables for one of the first suspended turntable de signs, pioneered by H. H. Scott. Also, despite the fussiness of tuning its de modulator, we used the Weathers FM arm and cartridge because it permit ted tracking vinyl records at 1 gram! There have been many milestones, many innovations and breakthroughs, along with many fads and foibles in the Audio has reporting on the hi-fi scene. The ubiquitous receiver exists because of the initially maligned transistor; in its tube embodiment, the receiver was a failure, due, of course, to overheating. Quadra phonic sound was a flop, partially be cause there were too many competing formats thrust upon the market before their technologies had been properly engineered, but also because placing discrete orchestral sounds behind the listener violated 300 years of traditional concert performances. Today, there is obviously a minor revival of surround sound, with the popularity of Dolby Surround-encoded videotapes. How ever, this is in a somewhat different context. Make no mistake: I think it is inevitable that we will eventually em ploy some sort of multi-dimensional sonic augmentation to simulate the experience of listening to music in a concert hall.

It is sad to note that in the 40-year history of hi-fi, many respected companies that helped to found the industry have vanished from the audio scene.

However, surely the saddest and most dramatic tale of all is the birth and death of the prerecorded open-reel tape, all within a span of 32 years. I am particularly distressed by this, since I was directly involved with its genesis.

For perhaps a year or two before 1954, there had been several small companies issuing prerecorded open-reel tapes. In 1954, 16 executives of RCA, including some from the broadcast and record divisions, were at Murray Crosby's laboratory in Syosset, Long Island, to hear a closed-circuit demonstration of the Crosby FM stereo multiplex system. I had arranged the session for Murray, initiated by the request of my friend Leopold Stokowski to David Sarnoff, head of RCA. The material for the closed-circuit broadcast was stereo tapes I had recorded with the Chicago, Detroit, and Minneapolis symphony orchestras. Now, these RCA officials had never heard stereophonic sound, let alone stereo FM multiplex! They were simply bowled over by it, and while they never did anything about the Crosby multiplex, the stereo sound inspired the record people to issue the first major-company, prerecorded open-reel tapes. Number one was the famous Fritz Reiner/Chicago Symphony recording of Richard Strauss' "Also Sprach Zarathustra." The format was half-track stereo-two tracks running in one direction. As I write this, I have RCA tape GCS-6 next to the typewriter. This was the sixth prerecorded open-reel tape RCA is sued, a recording of Charles Munch and the Boston Symphony playing "Symphonie Fantastique" by Berlioz.

Clearly printed on the tape box is the price, $18.95. Now, the next time you gripe about the $15.99 list price of a CD, translate that 1955 tape price into today's dollars! Back then, tape was the only way you could hear stereophonic sound, and for 32 years-well into the stereo LP era-thousands of great open-reel tapes poured forth from the duplicators. Alas, the encroachments of prerecorded cassettes and, more especially, the technical superiority of the Compact Disc put the nails in open reel's coffin. The Barclay-Crocker tape-duplicating people made a most valiant effort to keep open-reel tape alive, but in 1986 they too ceased operation. This signaled the final demise of a fine music format that was clearly the victim of advancing technology.

So congratulations to Audio on its 40th anniversary. This writer is glad to have participated in a lot of audio developments in that span of time.

(adapted from Audio magazine, May 1987; Bert Whyte)

= = = =