QUARTER NOTES

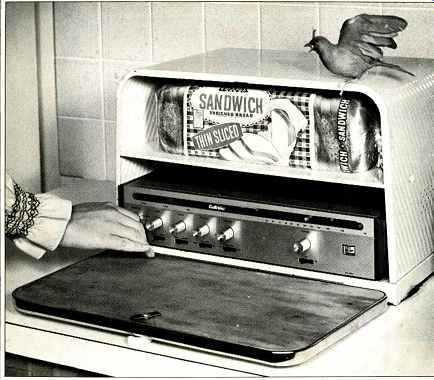

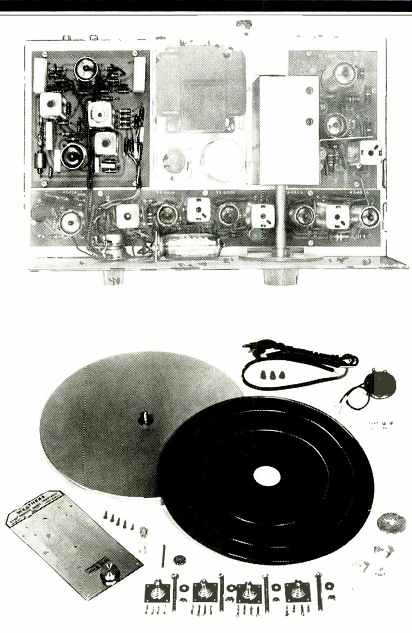

above: Early makers of solid-state equipment emphasized compactness, as in this mid-'60s publicity shot from Electro-Voice.

As of last month, Audio has been covering sound reproduction for 40 years. As of this month, I've been writing about it for 25. Since Leonard Feldman and Bert Whyte looked pretty thoroughly, in our anniversary issue, at what's happened in audio during the magazine's first 40 years, I thought I'd concentrate on what the field was like when I first officially entered it.

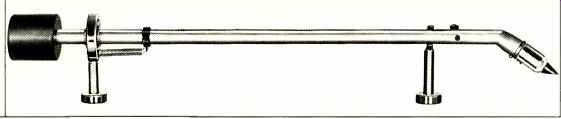

In 1962, a year out of college, I thought of myself as a newly minted hi fi buff (we weren't saying "audiophile" yet). Actually, I'd been one longer than I knew, ever since I'd bought the family's first 45-rpm changer from my birth day money and then urged the switch to LP in my Cub Scout days. In 1962 I was already on my fourth sound system, built around Dynakit tube electronics (PAS-2 preamp, FM tuner, and two 60-watt Mark III amplifiers). It included a kit-built Weathers turntable, a Dynaco/B & O integrated arm and pho no cartridge (capable of tracking with as little as 2 grams of force!), two 8-inch Wharfedale speakers in R/J enclosures, and a Magnecord PT-6 mono phonic recorder. As my college was all male and near no women's colleges, having this good an outfit owed as much to sublimation as to clever dealing and economizing.

I thought it an exciting time, with audio in a state of ferment. (Later I discovered that it almost always is.) The biggest news was that the FCC had just approved a "multiplex" system for FM broadcasting. Already, ac cording to a Sherwood ad, stereo FM was "an established reality," with 87 stations, in 29 states and Canada, either on the air in stereo or planning it.

New York City had two stereo stations on that list, though New Yorkers could also pick up stereo from nearby suburbs. Some stereo-casting was still being done the old-fashioned way, however, with one stereo channel on FM and the other on AM; by year's end, Audio was editorializing that it was time the FCC forbade the practice. You could still get tuners with separate AM and FM sections for simulcast stereo, but even these tuners (such as H. H. Scott's 333) had multiplex circuitry built in. If you had an older FM tuner, though, multiplex adaptors were pretty widely available from Eico, Eric, Fisher, Grommes, Knight, H. H. Scott, and others. There was also an internal adaptor, available from Dynaco.

Thanks in part to stereo FM but even more to the advent of the stereo LP, John Koss' bright idea of headphone listening was catching on fast. There was even one lightweight, on-the-ear phone available, the AKG Model K 50 ($22.50). My first two magazine articles, in fact, were on the several brands of phones available, and the little switch-boxes we used to hook them up to amplifiers (few audio components, if any, had headphone jacks yet). Edward Tatnall Canby, by then a long-time Audio contributor (as were Herman Burstein and Joseph Giovanelli), also devoted several columns to this new phenomenon.

above: The B & O Stereodyne cartridge tracked at a mere 2 grams!

I don't think I got the idea of writing about headphones from Mr. Canby (I read Audio only sporadically back in 1962, though I became a regular reader the next year), but he'd already been quite an influence on my career.

As the new audio columnist for Saturday Review, I was filling a post that had originated with him. And I had gotten my first grounding in hi-fi from the Saturday Review Home Book of Recorded Music and Sound Reproduction, which Mr. Canby had cowritten with C. G. Burke and Irving Kolodin. I also often listened to his radio program and almost felt I knew him.

Today's audiophile would feel only vaguely out of place in a hi-fi salon of 1962, but an audiophile from that era would be stunned by what he saw to day. On the phono side, we already had stereo records and moving-coil cartridges-but no controversy over whether they were generically better than other types. We also had belt-drive turntables with sub-platform suspensions: AR's was already on the market, and a Stromberg-Carlson had preceded it.

We also had four record speeds:

33 1/3 rpm, which is still going strong;

45 rpm, now an endangered species;

good old 78 rpm, which is still with us, and 16% rpm, which was then the newest and is now the deadest speed.

You could already buy several brands of S- or J-shaped arms with "universal" cartridge shells, then called "Ortofon" shells after the company whose arms had first used them.

Changers were still big sellers. Garrard had held first place for years, but I think Dual, with its clever 1006, had by 1962 already ousted Miracord from second place. There were ways to add a bit of automation to some manual arms too: Rek-O-Kut offered a motorized arm lift, and Empire had a magnetic end-of-record lift built into its arms.

The most advanced engineering, however, was in single-play tables.

Fairchild, for instance, offered an optional electronic speed control for its sleek 412 turntable, designed by Raymond Loewy. This was a tube oscillator which changed platter speeds by varying the power frequency fed to the table's motor.

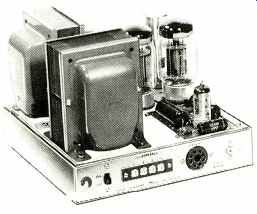

The cheery glow of tubes was everywhere.

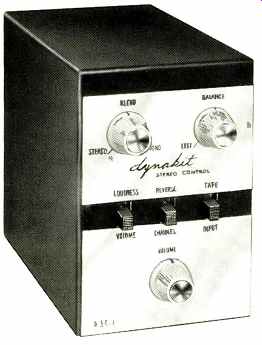

Stereo was new, so companies like Dyna made adaptors that could

link two mono preamps.

The Weathers I owned was simplicity itself, with only five parts. Instead of the usual approach, using a heavy platter for speed-smoothing momentum, the Weathers used a platter stamped from aluminum so light that an electric clock motor could drive it. What could be better regulated? Such a light platter could revolve on a single needle bearing, and the motor's torque was slight enough to be transmitted by a small wheel of soft gum rubber pressed against the platter's inner rim. Since gum rubber didn't take a set when left compressed, there was no need for a mechanism to move it to a rest position when the turntable was switched off.

Resonances galore, I'm sure, but still a lot of clever engineering.

Mono records were still being re viewed, but most new releases were stereo. Broadway show albums were far more common in those days, be cause there were still plenty of new Broadway musicals. The CBS STR-100 test record had just come out and was the subject of an article in Audio.

There were predictions that the LP would give way to tape-open-reel tape, that is. People thought the big breakthrough was 4-track tape, which got twice as much music onto a reel and required no rewinding. (You just flipped it over and played the other side.) You could get complete record/ play decks or more economical play back-only versions. Some of the latter had built-in playback preamps, but you could also buy a deck with only heads and get an amplifier with a tape-head input.

The predictions were wrong, of course, because consumers found tape too expensive and no one wanted to bother threading it. So the LP seemed even more threatened a year or two later, when a stereo system using an easy-load plastic package of narrow tape, running at 1 7/8 ips, hit the market. This wasn't today's cassette, however; it was part of a clever system from 3M which even included tape changers. But it never caught on.

When Philips did introduce today's cassette a few years after that, it was a low-fi, mono medium designed for voice applications.

In electronics, receivers were only just beginning to become popular as transistors started nudging tubes aside; Altec had a hybrid tube/transistor receiver, and I believe there were others at about that time. We did have some solid-state amplifiers (still uncommon, unreliable, and, I'm told, definitely guilty of "transistor sound"). The two brands I recall were the TEC components from Transis-Tronics (which were so small that it was obvious they were transistorized) and the low-slung, graceful Omega gear. Electro-Voice had transistor gear soon thereafter.

One premium name brand, Citation, announced solid-state equipment late in '62. There were no integrated circuits yet, and I think FETs, with their more tube-like characteristics, were yet to come. Digital tuner dials were also yet to come they're one of the features which solid-state design made practical.

Some of the features we did have then are rare today. In addition to tape-head inputs, center-channel outputs were popular. I don't remember whether that was for mono feeds to other rooms or to fill the "hole in the middle" left by the speakers and recordings of the day.

There were no black components.

Most were faced in some kind of brass or gold tone, though Harman/Kardon (which had formerly made copper-fronted components) was one of many companies offering a satin chrome or aluminum finish. There was even two tone equipment, such as Dynaco's brass and brown or Sherwood's brass and white.

Component audio was the esoteric high end of the day, as the average music-lover still bought a table model or console system. A high proportion of buyers of components were technically minded enough to build equipment from kits, and usually young enough, like me, to deeply appreciate the at tractive savings this entailed. Heathkit was still a major force (alas, they left the audio field last year), and the hot name was Dynakit. You could also buy kits from Knight (Allied Radio's house brand), Lafayette, Eico, PACO, and such major manufacturers as Fisher, H. H. Scott, and Harman/Kardon (both Citation and the lower priced Award series). Transvision, Heath, and others offered TV kits with cathode-follower audio outputs for integration with a sound system. Depending on the complexity of the component, savings could be substantial: Dyna's PAS-2 preamp was $60 in kit form and $100 wired, and Lafayette's KT-600A Criterion stereo preamp (a Stewart Hegeman design, I later learned) was $80 as a kit and $135 assembled.

You could get all kinds of stuff in kit form back then. I think tape deck kits only emerged later (I built a couple in the early '70s), but the Fairchild and Weathers turntables were available as kits (my Weathers cost me about $50).

Speaker kits were getting less popular since Acoustic Research's acoustic-suspension systems had popularized the idea of designing driver and enclosure together, but they were still avail able. So were plenty of bare drivers for those who wanted to build their own enclosures, and a dwindling few enclosures for those who wanted to choose drivers of their own.

There were already some electro static speakers, chiefly the JansZens.

A favorite audiophile system of the time was a JansZen midrange/tweeter with an AR-1W woofer (an AR-1 with its midrange, tweeter and crossover left out). Leak had a speaker with a sandwich cone-plastic foam with an aluminum-foil covering, as I recall. There were also thin enclosures, such as the wood-diaphragmed "Bi-Phonic Coupler" from Advanced Acoustics, and conventional cone-driver systems from Goodmans and Jensen. The only ad vantage cited for these systems was convenience-the room-boundary effects that Allison and Boston Acoustics now make so much of were unknown back then. Fisher predicted that its thinnish XP-4 would be "the world's most imitated speaker" because it had no frame; the magnet was fastened to the cabinet rear, and the surround to the cabinet's front panel.

(top) The board at the upper left adapted the Dynatuner to stereo

FM. (above) The Weathers turntable was simplicity itself and available as a kit for penurious

young men like me.

The world looked bright for the American hi-fi industry. Fisher had just opened a 50,000-square-foot plant in Pennsylvania, and at least one U.S. industrial giant, GE, still made cartridges, though it had scaled back from the full range of components it had offered in the '50s. (Stromberg Carlson, part of giant General Dynamics, had dropped out of audio a few years back.) Most audio brands were American and most of the rest were British, but the first Japanese components were already here, from Pioneer, Sony (mainly just stereo tape decks and small radios), and Onkyo (a motional-feedback speaker driver).

We "hi-fi nuts" still faced skepticism, even about such fundamentals as "spending all that money just for a phonograph" and the idea of stereo itself. As Audio editorialized: "Isn't it time that doubts about the value of stereo were laid to rest? We still hear relatively well informed people making the relatively uninformed statement that only the very critical and experienced few can tell mono from stereo."

(adapted from Audio magazine, June 1987)

= = = =