In spite of the introduction of magnetic tape and subsequent open-reel, cassette, and 8-track prerecorded for mats, the venerable phonograph record has remained the chief source of music for the audio consumer. Every time an advance was made in the magnetic recording medium, the doomsayers predicted the demise of the phonograph record. Subsequent technical shortcomings and economic considerations in prerecorded tapes kept the phonograph record flourishing. When stereo tape arrived on the audio scene in the early 1950s, it looked like this development would indeed mean the end of the phono graph disc. After all, how could stereophonic sound be recorded on a disc? Two sets of grooves on a disc were impractical for many reasons, and the notion of two signals contained in a single record groove was sheer fantasy.

Right? Wrong. Had the doomsayers delved deeply enough into the dusty archives of audio, they would have found that an unsung genius named Alan Blumlein had invented the single groove stereophonic disc in 1933! Per haps if Blumlein had not met his un timely death in an aircraft accident in England during the Second World War, the stereophonic phonograph record would have become a commercial reality long before 1958. In any case, over the years the phonograph disc has repeatedly demonstrated its technical resiliency and longevity.

Now, with the anticipation of digital disc recordings, a long road stretches ahead for the brainchild of Thomas Alva Edison and Emile Berliner.

All this preamble was in aid of the fact that if you have a phonograph record with grooves, you most assuredly have to have a phono pickup cartridge to trace the signals impressed in those record grooves.

While it might seem perfectly obvious that the phono cartridge is the first element in the audio chain of reproduction and, as such, can have a pro found effect on sound quality, the average audio consumer is usually more concerned with the nether end of the production chain, the loudspeaker.

When a music lover no longer is dazzled by the delights of his first audio system and begins to listen more critically, usually the first upgrading of his system is the acquisition of better quality loudspeakers. A bit later on, having become still more knowledgeable in the ways of audio, he opts for a better receiver or amplifier. Having advanced this far, he finally gets around to up dating his phono cartridge. Our newly minted audiophile has followed a well-worn route in the improvement of his sound system. Yet it is obvious, that even if our audiophile acquires the very best speaker on the market and the ne plus ultra in amplifiers, the entire system is only as good as the phono cartridge at the beginning of this audio chain. I personally feel that, all things considered, upgrading a phono cartridge is the quickest, surest, and usually least expensive way to improve the quality of a system.

Cartridge Configurations

Over the years, the quest for higher quality pickup cartridges has produced some unusual and very exotic configurations of this component. But basically we have had relatively few principles involved in these designs. Early on, we had pickups with crystal and ceramic elements which produced sound by their piezoelectric effects. A big step forward in the evolution of phono cartridges was the introduction of magnetic pickups. These employed such designs as variable reluctance, moving magnet, moving iron, induced magnet, and moving coils to generate an audio signal. Whatever the design, they shared in common a relatively low output, necessitating the use of a preamplifier and in the case of moving-coil pickups, a pre-preamplifier.

Needless to say, in the course of time some brands of magnetic cartridges have become pre-eminent and have dominated the field. In America such names as Shure and Pickering/Stanton come to mind. Between them they hold many of the basic patents for moving-magnet phono cartridges.

Moving-coil cartridges have always been considered fairly esoteric items or, if you will, in the province of audio faddists. Ortofon was the principal supplier of moving-coil pickups until recent years, when all of sudden there was quite a proliferation of these pickups from Japan. Now, among fanatic audiophiles, moving-coil pickups have acquired a whole "mystique" and have become a cult item, much to the dismay and chagrin of the moving-magnet pickup manufacturers. I has ten to add that their dismay is not in loss of sales, because the moving-coil market is miniscule in comparison to the world market for the moving-mag net types. Rather, the distress of these manufacturers is in the claims made for the superiority of the moving-coil designs. They consider these claims to be far-fetched, unfounded, and un-provable. Companies like Shure and Pickering/Stanton maintain elaborate and costly research facilities staffed by some very bright engineers, and they are ready at the drop of a stylus to refute the claims of the moving-coil camp. I should point out that Joe Gra do holds a number of patents on moving-coil cartridges in this country, but does not manufacture this type of pickup. There are also beady-eyed cynics who remind us that some of the Shure and Pickering/Stanton patents run out in two years, and that there are container ships loaded with moving-magnet cartridges sitting in Japanese harbors ready to flood this country with that type of pickup.

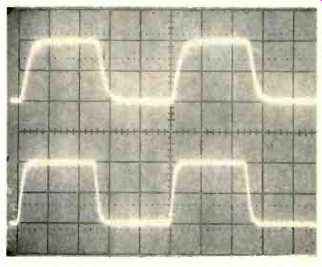

Fig. 1--Response of MX-10 pre preamp to 1-MHz square wave. Output level is

4 V p-p. Horizontal scale is 0.2 uS per division.

Moving-Coil Mania

What are some of the claims cited by the high-end audiophiles that make moving-coil pickups so desirable? They say that the lower moving mass of the MC pickup makes it easier to achieve lower stylus tip mass. Because the coils have few turns of wire in comparison to MM types of pickup, the inductance of moving-coil pickups is very low. The effect of this is to raise the resonance peak out of the audio range. Moving-coil pickups are regarded as having minimum hysteresis effects, and the flow of magnetic flux between poles is more balanced. MC aficionados say their pickups have higher definition, retain ambience and "air" around musical instruments, have lower and "tighter" bass response, give better stereo imaging and have more "musicality." Some audiophiles also feel that since records are cut with moving-coil cutting heads, playback with moving-coil pickups is a logical conclusion. This has been pretty thoroughly disproven, and even the hard core MC fanatics are acknowledging this to be so. The MM manufacturers can refute most of these claims with hard, cold figures to prove their point. They say that MC pickups cannot track as high a velocity signal as their MM units can. Further more, their pickups can track those velocities at much less stylus pressure.

The MM people can prove a flatter frequency response, casting an accusing finger at the rising high end response of a number of MC pickups. They point out the generally higher cost of MC pickups and the fact that some sort of voltage step-up device is a necessity.

This last is indeed the case, and the device can take the form of an electronic pre-preamplifier or a step-up transformer. Which brings me to the main thrust of this article. If, in spite of the challenges of the MM manufacturers to the claims of MC pickups, you still have a preference for the MC type of pickup, it is indisputable that the quality of sound of the pickup is profoundly influenced by the quality of the step-up device. Most of the MC manufacturers make step-up transformers, along with some from independent manufacturers. The best of these appears to be the high-priced Verion transformer, which is very care fully shielded and has no hum. How ever, there are many MC adherents who state that transformers are subject to hysteresis effects, core saturation, and that they degrade frequency and phase response.

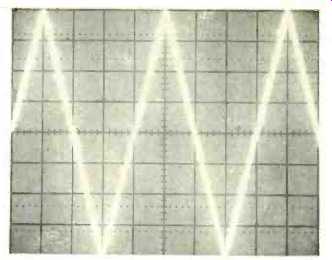

Fig. 2- Response to 125-kHz triangle wave at 4 V p-p. Horizontal scale is

2 NS per division.

I won't get into that dogfight, but there is no doubt that a great many MC faddists prefer pre-preamplifiers.

There must be at least a round dozen of these units on the market, and the audiophile press is constantly testing them, looking for a sort of "Holy Grail" that will provide the necessary step-up voltage for their MC pickups with a minimum of signal degradation.

I have tried a number of these devices with varying degrees of success. Recently I was sent a prototype model of a pre-preamp, and the results have been nothing short of phenomenal.

Every once in a while an item of audio equipment comes along that is so out standing in quality and innovative de sign that it sets new standards. The Mark Levinson LNP-2 preamplifier of some years ago was such a product. In the same lofty category is Audio Standards Corp. Model MX-10 moving-coil pre-preamplifier. The guiding light behind this unit is John Dunlavy, an engineer with formidable qualifications, who holds some 34 patents in the fields of antenna design and wave form theory. Many of the antennas on space vehicles orbiting the earth are of his design. Audio has been an abiding, if not over-riding addiction for most of his life, and the components he has designed reflect some very original thinking.

Pre-preamp "Specsmanship"

The MX-10 is larger and heavier than most such units on the market, and there is a very good reason for this. The unit is 6-in. high by 5 5/8-in. wide by 10-in. deep and weighs in at a substantial 15 pounds. A walnut enclosure contains the pre-preamp and a power supply. Each is in a separate shielded module which is made of a 4-inch diameter, 3/16-in. steel pipe. The end zaps are also steel, plated with 24K gold for maximum contact and mini mum corrosion. The power transformer is toroidal, and there is separate power supply filtering for each channel. The power supply is highly-regulated, maintaining 0.1 percent over an input range of 105 to 130 V or 210 to 260 V. The MX-10 is an all FET design, using selected very high transconductance, planar junction FETs. There is no inverse feedback in the circuit, and the slew rate is a rather incredible 400 volts per microsecond. Those who feel wide bandwidth is important should be happy with a frequency response whose-3 dB points are at 3 Hz and 10 megaHertz! The input impedance is 12 ohms, optimum for most MC pickups, and output impedance is 200 ohms.

Gain in the unit is 26 dB, channel balance is ±0.25 dB, and isolation be tween channels is greater than 95 dB (20 Hz-20 kHz). Dunlavy states the signal-to-noise ratio of his unit in a more accurate way than the usual spec employing various weighting factors, using equivalent input noise voltage, which is less than 0.6 nano-volts in a 1 Hz bandwidth referenced to the input, and equivalent input noise resistance, which is less than 25 ohms. This translates into a pre-preamp which is virtually noise and hum free.

To test transient intermodulation distortion in his pre-preamp, John uses the method of Otala, Curl, and Leinonen reported in the April, 1977, AES Journal. Using a square wave of 3.18 kHz (output level 400 mV) and a sine wave signal of 15 kHz (output level 100 mV), TIM is less than 0.002 percent, actually below the residual levels of almost all the measuring instruments. Harmonic distortion and intermodulation distortion are less than 0.003 percent for an output of 250 mV peak to peak, at any frequency from 5 Hz to 1 megaHertz. John offers an interesting new specification ... "propagation time, which is the delay time between the input and the out put, and in this MX-10 it is 35 nS. All these specs are very impressive, but the oscilloscope and spectrum analyzer photos are more so. How about a 1 megaHertz square wave at a hefty 4 volt peak to peak output, where the output trace is almost identical to the input trace! Or the linearity test using a 125-kHz triangular wave at 4 volts peak to peak, which shows the triangular wave as perfectly symmetrical. Most impressive of all is the spectrum analyzer photo of the Otala/Curl TIM square-wave/sine-wave test, which shows almost total lack of distortion, the harmonic, IM, and TIM components being down more than 90 dB! Obviously, the specifications of this MX-10 unit are an order of magnitude better than any unit I am familiar with, but as always, the most important question is ... how does it sound? The best answer to this is that it has no sound. It's as if there was no pre preamp at all between the moving-coil cartridge and the input of the preamplifier. I have tried the MX-10 with the Supex Super 900 plus, the Fidelity Research FR1 Mark 3F, the Ortofon MC20, the Denon 103S, and experimental moving-coil cartridges from JVC and Technics. The sound from all of these pickups was vastly improved over any previously heard through quite a number of step-up devices.

Even if you are a dyed-in-the-wool moving-coil enthusiast, you won't believe how good a MC cartridge can sound with this unit. The combination of the MX-10 and the Supex was out standing, affording utterly effortless, smooth, yet highly detailed sound, quite transparent and completely free of coloration. In short, if the moving-coil cartridge is your bag, in my opinion this MX-10 is the premier pre preamp available today.

Speaking of availability, John Dunlavy tells me that his unit will ultimately be sold in selected high-end audio dealers, but at present can be obtained directly from his company ... Audio Standards Corp., Post Office Drawer 2529, Las Cruces, New Mexico 88001.

The price is $299.95. Finally, as a teaser, John Dunlavy gave me a few details about his upcoming preamplifier, which apparently will be as advanced and innovative as his pre-preamp. But that for a later installment.

(Source: Audio magazine, Nov. 1978; Bert Whyte)

= = = =