Manufacturer's Specifications:

Type: Air condenser, internally pre polarized backplate.

Type 4003, low-noise; Type 4007, high-intensity.

On-Axis Frequency Response: Type 4003, 20 Hz to 20 kHz, ±2 dB; Type 4007, 20 Hz to 40 kHz, ±2 dB.

Phase Matching Between Microphones: From 50 Hz to 20 kHz.

Type 4003, ± 10°; Type 4007, ±5°.

Sensitivity at 250 Hz: Type 4003, 50 mV/Pa, unloaded (-26 dBV); Type 4007, 2.5 mV/Pa, unloaded (-52 dBV).

Equivalent Noise Level: Type 4003, 15 dBA typical, 17 dBA max.; Type 4007, 24 dBA typical, 26 dBA max.

Harmonic Distortion: Type 4003, 1% at 135 dB peak SPL; Type 4007, 1% at 148 dB peak SPL above 100 Hz.

Maximum Sound Pressure Level: Type 4003, 154 dB peak SPL at or below 4 kHz; Type 4007, 155 dB peak SPL above 200 Hz.

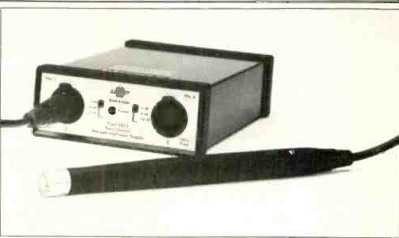

Power Supply: Type 4003, 130 V, from Type 2812 two-channel power supply; Type 4007, 48 V, phantom power per DIN 45 596.

Audio Output: Type 4003, balanced, transformerless, line level from XLR-3 male jack on Type 2812 power supply; Type 4007, balanced, transformer isolated, microphone level, from XLR-3 male jack on microphone.

Weight: 5.3 oz. (150 grams).

Dimensions: 6 1/2 in. (165 mm) L; cartridge diameter, Type 4003, 3/8 in. (16 mm); cartridge diameter, Type 4007, 1/2 in. (12 mm).

Price: Type 4003 (inc. diffuse-field grid, power-supply cable, windscreen and clamp), $705.00; Type 4007 (inc. audio cable, windscreen and clamp), $765.00; Type 2812 power supply for 4003, $1,085.00.

Company Address: 185 Forest St., Marlborough, Mass. 01752.

Brüel & Kjaer is a Danish firm which has produced condenser microphones for use with their well-known line of sound measuring instruments since 1959. Now there are B & K Studio Microphones as well, of which two (the Type 4003 and Type 4007) are reviewed here.

Brüel & Kjaer's instrumentation microphones are optimized for frequency response and polar pattern, but not for low noise level. They are suitable for recording relatively loud instruments at close distance. In contrast, these studio microphones are optimized for dynamic range, frequency, and phase response and are specifically intended for music recording. They are pre-polarized, charged-backplate types which have metallic diaphragms for optimum response, corrosion resistance, and stable output with temperature changes.

Those who have not used Brüel & Kjaer sound instruments may have some difficulty in understanding the differences in acoustical properties of the various studio microphone types. B & K publishes an instruction manual for the microphones which gives much detail not included in the sales brochure. I will try to offer a brief, simplified explanation below.

The Studio Microphones are omnidirectional, pressure sensing types, same as the instrumentation models. Cardioid capsules are not presently available; thus, the B & K mikes are not suited to X-Y coincident-microphone stereo pickup. Applications are therefore limited to spaced-microphone stereo pickup, as in classical music, or close miking of instruments in multi-channel pop-music recording.

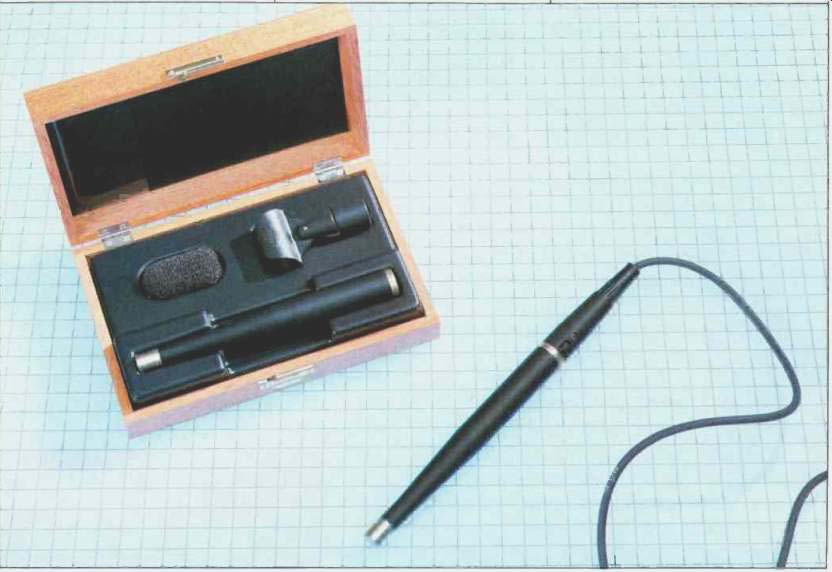

There are four B & K Studio Microphones. They differ in capsule size (16-mm diameter for the Types 4003 and 4006, 12 mm for the 4004 and 4007) and in power supply (130 V for the 4003 and 4004, 48-V "phantom" power for the 4006 and 4007). In order to evaluate both capsule sizes and powering options, I tested a pair of Type 4003 (16-mm capsule, 130-V supply) and a pair of Type 4007 (12-mm capsule, 48-V supply) microphones.

These microphones are ultrahigh quality, omnidirectional condensers whose specifications complement the dynamic bandwidth of such new-technology recording systems as digital and direct-to-disc. They should also be of interest to amateur and professional recordists who have high-quality open-reel recorders. Some of the high-end cassette recorders will also benefit from higher quality microphones.

The prices of these microphones are high compared to those in past reviews, but since the microphone is the controlling "filter" in most recording systems, I believe that it is wise to spend more on microphones than on the recorder.

Basic Characteristics

My rule of thumb on microphone capsule size is that condenser microphones 16 mm and smaller in diameter potentially offer uniform frequency response and polar pattern to 15 kHz. This is true of both mikes under review.

However, small microphones may have high electrical noise, which reduces dynamic range. Brüel & Kjaer has achieved a low (15-dBA) noise level in the 16-mm Type 4003 (and 4006). Thus, the specifications show excellent acoustical response for all musical applications, but low enough noise for distant miking of classical music. The 154dB SPL limit of the Type 4003 results in a dynamic range of 154-15 = 139 decibels, adequate for any recording and playback system known today. The noise levels of the 12 mm Type 4007 (and 4004) are higher (24 dBA) than that of the 16-mm microphones. However, the very high maximum SPL of the 12-mm models results in a wide dynamic range: For the 4004, using the same power supply as the 4003, maximum SPL is 168 dB, resulting in a dynamic range of 144 dB (168 24 dB). The Type 4007 tested here has a maximum SPL of 155 dB because of its lower power-supply voltage.

The 4003 and the other 16-mm model are furnished with removable, gridded caps which offer two choices of acoustic response: The bright plated cap yields flat axial (0°) high frequency response. The response to a diffuse field (as well as the 90° response) is rolled off above 5 kHz. In a typical, somewhat live room, a microphone is exposed to a diffuse field when it is more than a few meters from a musical instrument. A diffuse field is one in which sound reaches the microphone from many, random, directions. In other words, the sound which is reflected from many room surfaces is equal or greater in intensity to the direct sound from the instrument. Thus, the bright cap is properly used only for close miking (within about 1 meter or less), with the mike pointed at the instrument or vocalist.

The black-gridded cap modifies the response so that the diffuse (which resembles the 90°) response is essentially flat to 15 kHz. In contrast, the axial (0°) response is specified to have a 6-dB peak at 12 kHz with the black cap. Thus, the 4003 or 4006 microphone with the black cap is properly used in a diffuse field, at a distance from sound sources. A good method is to point the mike at the ceiling because response to direct sound at 90° is flat, and response to the randomly reflected (diffuse) sound is also flat.

With the 12-mm cartridge of the 4007 (and the 4004), both the axial and diffuse responses are essentially flat, and so no removable gridded caps are provided. However, because of both the higher noise level and higher SPL tolerance of the 12-mm models, referred to earlier, these microphones are billed as High Intensity models, properly used close to the sound source.

As mentioned above, I tested both 130-V and 48-V models. The Type 4003 is powered by 130 V from B & K's Type 2812 power supply, to which it is linked by a special 15-foot cable. (Cable extensions up to 45 feet may be used in many circumstances.) This higher voltage to the microphone preamp results in a higher SPL capability than the lower voltage model has, and a transformerless, balanced output specified as being at line level. When used with a transformerless input circuit, flat response and low distortion are assured down to below 20 Hz.

The Type 4007 operates on "phantom" power, supplied through the regular microphone cable, at a nominal 48 V. That figure represents the open-circuit output of the power supply, and is dropped to a lower value by a series resistor in the power supply. The actual voltage at the microphone therefore depends on the value of this resistor and the microphone's own current draw. Despite an applicable DIN standard, there is considerable variation in these characteristics among the various makes, and sometimes between different models of a given make. Brüel & Kjaer offers no 48V power supply of its own, but I was informed by its U.S. headquarters that the microphone should ideally receive 36 V. (Unfortunately, this information is not in the instruction manual.) I would caution users to check that the voltage at the mike is 36 V, ± 10%, in order not to compromise performance of these very high-quality microphones. To calculate if a particular power supply will be adequate, use 3.5 to 4.0 mA per mike as the current at 36 V. I hope that B & K will soon offer a 48-V phantom supply as an accessory.

The Studio Microphone capsules are not user-removable from the preamp bodies, which is different from the design of the B & K instrumentation mikes and other commercial condenser microphones. So, if the capsule is damaged, as sometimes happens with Sound Level Meter microphones, you cannot replace it in the field. Also, this limits future interchangeability with newly designed capsules. A cardioid capsule is an obviously desirable accessory.

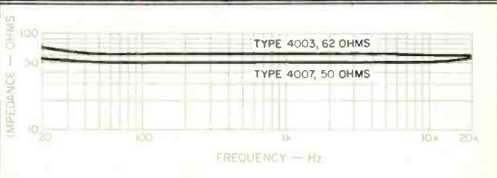

Fig. 1-Impedance vs. frequency (balanced output mode).

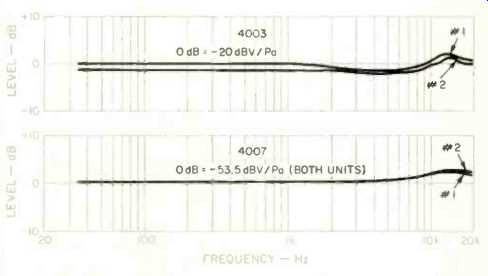

Fig. 2-Axial frequency response.

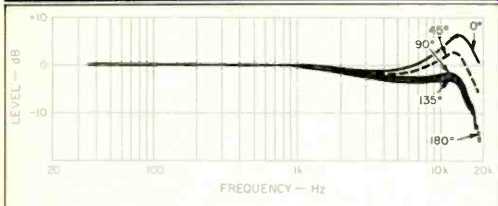

Fig. 3-Frequency response vs. angle, Type 4007.

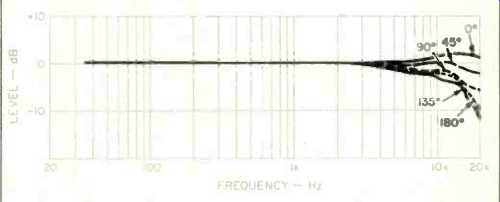

Fig. 4--Frequency response vs. angle, Type 4003 with bright gridded cap.

Measurements

Each Studio Microphone comes with a calibration chart showing complete measured data. The accuracy is unquestionable, as the Brüel & Kjaer laboratory in Copenhagen is comparable to the lab at our National Bureau of Standards.

Therefore, much of my work consisted simply of verifying this data. The calibration chart is a plus to professional users who have equipment for measuring frequency response, such as real-time analyzers, TDS systems, or a strip chart and oscillator such as I have. Thus, a B & K Studio Microphone can serve as a reference in microphone and loudspeaker testing in the field.

I must emphasize that I did not evaluate new, randomly selected microphones. These were microphones from the West Coast regional demo stock. The mikes showed evidence of being used, as some dust was seen on the diaphragms with a magnifying glass. B & K is currently loaning mikes for studios to try before buying, so both new and demo stocks are quite short at this time. This reflects present demand for these mikes for professional recording, and B & K is now setting up a dealer network.

As mentioned above, B & K provides no power supply for its 48-V models, leaving that responsibility to the user. The only such supply I had available, an AKG, had too much resistance for these microphones, yielding only 27 V at the mikes. I therefore powered the Type 4007 in these tests with four 9-V batteries in series, connected to the center top of a UTC HA-108X line transformer, which was set for 200:200 ohms. Thus, with low series resistance, there was certain to be nearly 36 V at the microphone. The UTC transformer is very well shielded, has flat response from about 10 Hz to 50 kHz, and will handle up to +20 dBm levels in the audio frequency range without distortion.

The 4003 was powered by the 2812 power supply. This is a totally transformerless, line-level output system. Since the 4003 has response down to 5 Hz, many input transformers with small cores may introduce distortion due to magnetic core saturation on high-level, low-frequency tones, such as organ-pedal notes at 16 Hz. I found that the "line-level" output of the 4003 (-20 dBV at 94 dB SPL or 1 Pa) was about 20 dB too low for any of my line inputs, but 30 dB higher than appropriate for low-impedance microphone inputs. From time to time, I had trouble with hum ground loops between the 2812 supply and my mike preamps, so I opted to use a 30-dB pad plus an HA-108X transformer (200:200 ohms) for frequency response and listening tests. Thus, the 4003 and 4007 were each tested with a transformer and, at equivalent audio output levels, into standard balanced, low impedance microphone inputs. There was very little possibility that the very large HA-108X transformer core saturated during testing or music recordings.

The measured impedances versus frequency are shown in Fig. 1. These are the impedances seen by the primaries of my isolation transformers, without the resistive pad on the 4003. The 50and 62-ohm impedance values, when used with unloaded 150/250-ohm inputs of domestic preamps, might possibly cause higher noise in any input stages which require a 150- or 250-ohm termination for minimum noise.

Also, mismatch can upset the frequency response of some preamps. Note that most Japanese-made microphones I've reviewed measure 600 ohms. In my opinion, equipment manufacturers should not have to design for a 10-to-1 range of microphone impedances. Fortunately, my isolation transformers added resistance in series with the microphones, so the test preamp and tape recorders saw about 150 ohms.

The mikes easily met their noise specifications with this added resistance.

Figure 2 shows that all four mikes conformed to their frequency response specs. Frequency responses of the two pairs matched closely, and only the 4003s showed a 1.5-dB difference in output levels. The flat trend of the 4003's axial response curves reflects the use of the "close-miking" bright grid.

Open-circuit output levels of the 4007s were 1.5 dB below nominal, and the 4003s measured +4.5 and +6 dB re: nominal value. The transformerless output of the electronically balanced 2812 necessarily has its midpoint grounded, whereas a transformer balanced output can be floating. So, if I had measured the 4003s with an unbalanced input, the output levels would be 6 dB lower, conforming to specifications. In my music recordings, I used a 30-dB pad with the 4003s, with calculations based on-20 dBV output level, so I am convinced that the 6-dB difference is simply an artifact of measurement technique.

Figure 3 shows that the 4007 has essentially flat response to 15 kHz over its front hemisphere (0° to ± 90°). The diffuse field response may be assumed to be similarly flat.

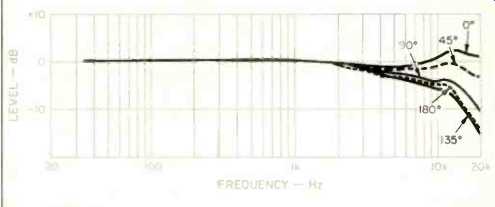

In contrast, the 4003's response with the bright grid is flat only from 0° to ±45° (Fig. 4). The 90° (and diffuse-field) responses roll off above 5 kHz. Figure 5 shows how the black grid flattens the 90° (and diffuse) response to 15 kHz, while the on-axis response peaks at about 14 kHz.

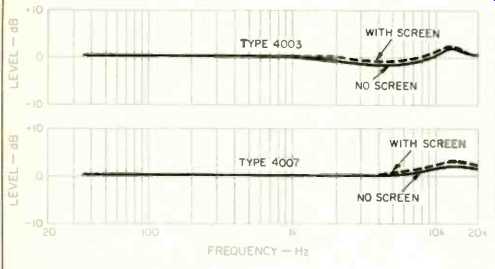

Figure 6 shows how the windscreens increase the high frequency output of the Type 4003 and Type 4007 by about 1 dB over a broad range. This contrasts with most of the larger, "Nerf-ball" windscreens, which cause about 1.5 dB of loss at 10 kHz. B & K has stated in previous publications that windscreens protect condenser microphones from dirt and corrosion, and I recommend that they be used on the Studio Microphones at all times.

Fig. 5--Frequency response vs. angle, Type 4003 with black gridded cap.

Fig. 6--Effect of windscreens on axial response, Type 4003 with bright gridded

cap and Type 4007.

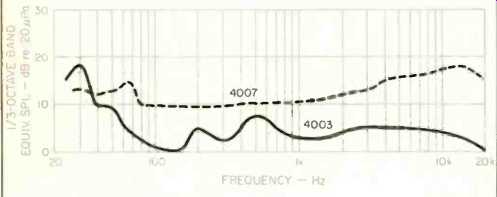

Fig. 7--Noise spectra for Type 4007 (overall noise level, 24 dBA, 26.5 dB

unweighted) and Type 4003 (overall noise level, 14 dBA, 21 dB unweighted).

Noise measurement was most difficult because, even though I used a sound-attenuation box with about 40 dB of loss, the very low noise level of the 4003 meant that the tests had to be conducted at night, when outside ambient noise was at a minimum. Figure 7 shows the 1/3-octave noise analysis of the 4003 and 4007. The 4003's equivalent noise level was 14 dBA, well within the 17-dBA specification.

Unweighted noise was a very low 21 dB. Previously, I had thought that only a microphone with a 1-inch diaphragm could have this low a noise level. (As explained in the September 1978 issue, I use an old RCA tube amplifier, Type OP-6, for noise measurements. This amp band-limits noise to a range from 30 Hz to 15 kHz and, according to my latest test, measures less than -130 dBm equivalent input noise level. In 1978, I asked readers to write us of a solid-state preamp with equivalent or lower noise; we are still waiting for an answer.) Phasing, as measured with an EMT-160 polarity tester, was pin 2 plus, in accordance with EIA specifications, for both models. Because of the extended low-frequency responses of the 4003 and 4007, their windscreens do not entirely cure breath pop or wind noise which is manifest as a very low-frequency thump. Low-frequency noise is also heard if one moves either microphone rapidly without a windscreen. Thus, the Studio Microphones should not be used as hand-held vocalist's microphones; there are plenty of cheaper mikes to serve this purpose. The Studio Microphones were found to have negligible vibration or shock sensitivity. Magnetic hum pickup of the 4003 was about 20 dB less than that of my comparison mike, a Nakamichi CM 700 with omnidirectional capsule. The 4007 showed only about 2 dB higher hum pickup than the 4003, even though the 4007 has a transformer and the 4003 does not.

While making hum and noise tests, it was imperative to ground the chassis of the 2812 power supply to avoid hum.

Unlike B & K instrumentation-mike power supplies, the 2812 has no provision for a three-wire grounded power cord. I found that sometimes a grounded cord was needed and had to substitute a clip lead. I hope that this problem will be taken care of.

Table I--Specifications of Type 4004 and Type 4006 microphones.

Sensitivity at 250 Hz: Type 4004, 10 mV/Pa, unloaded (40 dBV); Type 4006, 12.5 mV/Pa, unloaded (38 dBV). Harmonic Distortion: Type 4004, 1% at 148 dB peak SPL, below 20 kHz; Type 4006, 1% at 135 dB peak SPL, above 100 Hz.

Maximum Sound Pressure Level: Type 4004, 168 dB peak SPL, at or below 4 kHz; Type 4006, 143 dB peak SPL, above 200 Hz.

All Other Specifications: Type 4004, same as 4007, except audio output, power supply and price same as 4003; Type 4006, same as Type 4003, except audio output, power supply and price same as 4007.

Use and Listening Tests

Voice pickup quality of the 4003 with bright grid, the 4007, and a Nakamichi CM-700 with the omni capsule were quite similar for any orientation of the microphones.

The 4003s were used to record a festive concert and church service in the large 1,000-seat sanctuary of my local Methodist church. Empty, the reverberation time is 2.5 to 3.0 S, but with a full house for this service, acoustics were less live. The 4003s were mounted vertically about 6 inches apart, according to suggestions from a Brüel & Kjaer field engineer, and located off-center at the front of the nave seating area. The black grids were used, because the musical instruments of a brass quintet were about 10 feet away in the chancel, and a bell choir was about 20 feet away in the transept. Organ pipes were in the front and back of the church, and the choir in the front. A Revox open reel recorder was in a remote control room, requiring the 2812 power supply outputs to connect to house mike lines about 200 feet long. The 2812 chassis was not grounded, but perhaps should have been, because I had to play with the grounding of the two HA-108X isolation transformers plus the two 30-dB pads located at the Revox. I used the Revox's low-impedance mike inputs. Without the transformers for isolation and balancing, hum was clearly audible.

I listened to the tape in my acoustically dead listening room over my modified and equalized Altec 604C 15-inch coaxial speakers. Several years ago, I had tried Nakamichi omnis, spaced at 10 feet, for recording in the church, but imaging was poor and the ambience or room sound was annoying. With the closely spaced B & K 4003s, the imaging was excellent and the ambience exciting rather than annoying. The ye-service brass music was brilliant in the highs and well imaged in spite of the unfavorable position of the mikes, off-center of the ensemble and only 4 feet from the floor (so as to be inconspicuous). The bells were crisp and well defined in space in spite of their distant location.

During the processional (O Come All Ye Faithful"), the brass and organ were playing at maximum level, the congregation of 1,000 was singing, and the choir was singing as it marched down the aisle. The bass sound of the organ seemed about an octave deeper and more full than on any previous tape. The brass was clearly heard above the singing, which seemed to fill my listening room, similar to the live listening experience. The overall result was a dazzling recording which I have used several times as a demo tape to impress people with the sound of the B & K mikes and my playback equipment.

I was able to compare the above tape with one made a year earlier with coincident Nakamichi CM-700 cardioids on a 14-foot-tall stand. The musical instruments, musicians, and program were essentially the same. The exciting ambience of the singing was lost with the Nakamichi mikes.

Imaging of the brass quintet was little improved by the more favorably situated cardioids. The brass sound was brilliant and quite similar to that from the B & K mikes, reflecting that both mikes have 16-mm capsules. The congregational singing was poorly defined by the cardioids, and the firm bass of the B & K tape was missing in the Nakamichi tape. So, my first-rate recording of 1983 became second-rate by comparison to the 1984 tape.

The 4003s were then used to record a string quartet in a neighboring Presbyterian church, with similar placement of the mikes-6 inches apart on a low stand. Again, the black grids were used and the strings sounded brilliant and well imaged. Of course, this tape did not reveal the outstanding bass response of the 4003s. At no time was any microphone noise evident.

Owing to a shortage of timely concerts, plus the success enjoyed with the 4003s, I had no opportunity to record with the 4007s. Besides, these are best used for multi-channel miking of pop music, which I never do. This I leave as an exercise for the reader. Since the 4007s are miniature versions of the 4003s, sound quality should be equal or better.

Noise level is low enough for pop recordings or for most uses in close-miking instruments. With either model of phantom-powered mike, low-frequency distortion could be en countered if the integral transformers become saturated.

Obviously, for low-frequency, high-intensity sound pickup, the 130-V, transformerless models are best.

Conclusion The Brüel & Kjaer Studio Microphones are easily the best I've tested in seven years of reviews for Audio, but are also the most expensive ones. The treble sound was not noticeably better than that of a low-cost 16-mm microphone, the Nakamichi (but note that the latter microphone is no longer on the market). My comparison recordings with brass instruments were not very well suited to revealing differences at 10 kHz or higher. The extended bass response was very noticeable, compared to my reference, so I think that the 4003 is quite superior for recording pipe organ; the spacious room sound was quite impressive.

It is obvious that these omnidirectional microphones are suited to close miking of musical instruments, but the very low noise level of the 4003 makes it ideal for distant miking of soft classical music, such as string quartets. Initially, I thought that the omni pattern would make these mikes useless for single-location stereo pickup, but with 6-inch spacing, stereo imaging was excellent.

I can highly recommend the B & K Studio Microphones for most all music recording applications.

-Jon R. Sank

(Source: Audio magazine, Nov. 1984)

= = = =

Also see: Link | --Brüel & Kjaer 4011 Studio Microphone (Jan. 1990)