by Paul Laurence and Bob Rypinski

Paul Laurence: first off, how do you approach recording?

Les Paul: You know what? When I make a record, I don't turn any knobs.

My engineer sits there and shakes his head. And l'l1 make a whole record and never touch a knob. No EQ, no echo, no nothin'. Then I'll go to the second part while you wind the tape, lay the second part down, then I do third part, fourth part --the whole number. In 10 minutes! Now here we got three cameras on me, from Germany. For the Armed Forces Radio and TV, and they have these cameras for Public Service Television, and the guy says "Now for the next two hours..." and I says "Uh, uh..." I says "Hans"... to the German. "Hans, get the three cameras goin'. Have 'em loaded. And we're gonna do the multi." Well he said "We'll have to stop and reload" and I said "We won't have to stop and reload. It'll be done." He says "You don't understand. We're gonna do the whole multiple." I said "You don't understand --the whole multiple's done. By the time you run out of film, the thing is done." So he says .-- "Well, let's see. Let's see." He spoke pretty good English. So they got the three cameras running .... First I asked them what they wanted to hear. He said "Do you know any dirty blues?" I said "I got it down, just as dirty as you wanna get a blues." I said "You want some real funky blues?" So I lay the tracks down there and he's lookin' at this tape whizzin' back and forth and...touchin' the button and playin' the parts and the second part and the third part and he sees the bass. . .1 haven't laid the guitar down once! Right? The tracks are all filled up and I say "There you are." Then I punch the button and play it back. I don't mix --it's already mixed! No automated mixdown, no nothin', it's mixed! So it went from the 8-track to the 2-track and it's done and I says "There you are." They had a 16-track sittin' there. I didn't even use the 16, I just said "There it is." And they did it all on one take on the film. He's called me from Germany, he's called me from California...I guess if he had a chance to get to Alaska he'd call me from there. All he wants to do is redo that.

And he says "Slow it down for God's sake. Nobody believes me! They think we chopped it out and edited and everything."

PL: "Simulated for television."

LP: Yeah, but he says "It went so fast, it's a blur." And I says "This is the way I do it." And it takes 20 minutes to make Tennessee Waltz or whatever the song is. Well, what are we foolin' around with? You're layin' a part down, you lay the part down, dum dum dum dum dum, it's down.

Rewind the tape, dum dum dum dum dum dum next part. . .He says "You know what you're doin'?" "There it is it's done." And the kid today, he's got this flyin' machine, and rightfully so .... You know, like I said, the producer over there, he's got a board that will drive anybody up a wall. Turn it wide open to get the guy with the money with that glaze in his eyes .... Well, you know, the biggest crap table in the whole world is in the record business, right? And you get this angel with the money, and you get the Great Pretenders up there, turn 'em wide open (LAUGHTER). And sell, right? Set the clock ahead if he's not lookin'. But in my department, it's a different world. I just say "I want to get the thing done, I know what I want to do." Then I don't listen to it back. It's on there, I'm done, I never play my records.

Bob Rypinski: There's a question that I'm dying to ask that bears on this subject. When you started with the disc--to-disc-to-disc multitrack. ..1 don't really know enough about disc recording to say, but 1 know that in tape recording when you go from copy to copy, you get a 3-dB degradation each time.

LP: Well, there is modulation on the tape and there's intermodulation and there's harmonic distortion which is associated with the intermodulation ... . And there is the frequency response which is not exactly linear because of head bump, which is at the low end of the audio spectrum, and that head bump is determined by the speed. If it's at 15, you're gonna have a head bump, we'll say, at 50 cycles, and if you go at 7 1/2, it's gonna drop down to one octave below that--25 cycles

so that head bump has to be removed. And so at a very early age I immediately had to have linear response so that when I did my overdubbing, it was linear. Now this applied the same thing to disc, but with this machine, if I was 1/8 dB off...Hell broke over, because I don't wanna be a quarter dB off.

BR: But weren't you degrading each o the early tracks with each track that you added?

LP: 'Course you degrade. But the de grading depends upon what you're degrading. You're at the Hilton Hotel, and you don't know what we're sittin' on down underneath the hotel, do ya? Okay, on my recording we don't know what's down underneath, and the parts that are the least important are the parts I put on first. One of the big secrets of sound-on-sound is that you save your goodies for the last. So if you're going to put somethin' unimportant on, let it be a little worse. Like a drum is in the background, he's just stirrin' around, he's unimportant--put him back there or rhythm guitar.

So he's not important, but you get that bass, you gotta have him right up front, and you better have him just right. That lead guitar better shine, and he better be brand new. That vocal better be so clear that the four-part harmony may be off in echo and it may be half a block away. So your perspective has to be in your mind. You have to have this vision.

First of all, it is terribly important that the person sitting on this side of the room is receiving the bass because the bass is the leader of the band.

Now, very few people know this, but the leader of the band is the bass. Because you gotta go "boom-ta." Now if you got "ta" and no "boom" ... you're in trouble. So the leader of the band is the bass note. Now if you're gonna do it with your foot--today's foot player, he's a real happy guy with that foot.

And that foot may be all over the place, and he may be playin' in all kinds of figurations, okay? If he's the leader of the band, then the foot is also the leader, and the bass guitar or standup bass becomes secondary. But as a rule, the bass is the leader of the band, and the "tuck" is secondary.

Your tempo is set by "bom bom bom bom" --there's your tempo. That's your tick-tock. So you start with him.

So, you want him on one side, then the guy on the other side says "What the hell happened to my rhythm section?" So you put him in the center.

I wouldn't think of puttin' the bass on one side, even if there were only two guys, me and a bass. And it was a stereo record with just a bass and a guitar, I would not put the bass on one side.

PL: Back in the 4-track days, when people would record the bass and drums on the same track, I would say it, more often than not, was on the side.

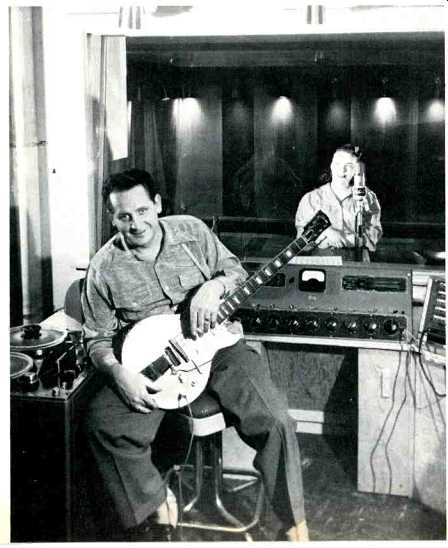

--------Les Paul and Mary Ford in an early Capitol studio.

LP: Yeah, well, they were ping-ponging, they were doing all kinds of things, and they had some toys to work with. I was more interested in getting the sound that was pleasurable. But as far as I'm concerned, I don't want to sit there and hear a train go by. I never was there and I'm not gonna go there. I'm there to enjoy the music. And I don't care if they get it in mono. I am not a freak that cares whether it's mono, stereo, quad -- I don't flip over any of it. You just give me the message. You can play it anywhere --on a Bozo record player, and I'll get the message that he's playin' I Can't Get Started. And if a classic is there, I don't care if you play it with a cactus needle. It's got it. And I think a recording is the same way -- a good classic recording, if it's good judgment and done well and if the bass deserves to be on the left for a very good reason, then put it on the left. Generally speaking, I'm saying "I don't want to say I want you to sit here, in one spot in a room to enjoy a record'." You should sit anywhere in the room and enjoy a record. And I think it's wrong that the wife --who is the biggest obstacle within our course --says "In the house you're not gonna put those two speakers there." And eight tape machines. "Get 'em out of here," right? So you got a constant battle with the lady of the house because she's looking at it from a cosmetic point. She wants a beautiful room and you want some machinery in it. Well, this machinery's gotta sort of blend in with the thing. When you come into the room, you're liable to plunk anywhere. It don't sound right here, so everybody's crowded over there. So it just doesn't make it. Your sound should sound good anywhere. If you go to our house, when you listen, you can sit anywhere in the control room, and say "man, that's a hit" or "It's great" or whatever's wrong, and you're in perspective, no matter where you're at. This idea that you have to sit on a pinpoint here .... And not that I don't measure it off with a piece of string, because I do. When I set my speakers up, I put right in the center of that speaker a piece of string, and bring it to my ear --where I'm gonna sit --and I take a string from that second speaker, it's the same distance.

BR: You have an equilateral triangle.

LP: You better believe it. By knowing exactly where it is, because now I have to know exactly what is going on. But as far as the guy next to me is concerned, he also has to be happy. So have my speakers aimed at the client.

want to make sure he's happy, that he's hearing whatever he wants to hear and so forth and so on. So everybody in the room, they're happy. It's the most important part about the control room. When I sell my own records, but when I think of somebody else I always think .... You know, the client --the angel. I call him "the angel." This is an important man in the record business.

BR: Did you emerge from being a performer to a producer after you got your own studio?

LP: No. Started out the same day. The same year. I was in electronics at the same time I was in music, and they parallel, and like I said --my mother said "You're gonna be a fireman, and it'll make up your mind what you're gonna be."

BR: You said in your bio that when Meredith Willson recruited you for the army, you played with lots of people now you weren't producing those records?

LP: Oh, no, oh, no. If you mean later in life, I worked for Bing Crosby --I didn't produce his show, and I didn't produce in the army. I did produce my own shows in the army, yes.

BR: Well, how about that record you made --the Grand Award record was it?

LP: Chester and Lester ?

BR: No, no. The one you made with Nat Cole .. .

LP: Oh, Jazz at the Philharmonic?

BR: Did you produce that?

LP: No, I didn't produce it. What I did ... it's a funny story. Oscar Moore was playing guitar with Nat Cole. And Oscar had found a gal that he liked very much and locked himself up in the tower somewhere ... here in Hollywood ... and wouldn't come down --they were shovin' food under the door.

PL: Just tortillas.

LP: Yeah, just tortillas --flat food (Laughter). So Nat called me and he says "Hey, uh . . . I lost my guitar player." He says "Can you play for me?" and I says "Well, I'm in uniform.

I'll have to ask my commanding officer." I says "Can I play a thing for Norman Granz? Jazz thing." Well, they weren't too enthused about jazz but he said "S'long's you wear a uniform, go ahead and do it." We went over, and I'm the only white man in the group that I remember. I don't remember any other one, but maybe there was another one. Anyway, Nat and I are old friends from back in Chicago. . .. So are all the rest of 'em. Anyway, we're playing, and again, from a showman's standpoint, I'm interested in showmanship. You put a guitar in my hands, and immediately I'm gonna get ... she's there, I'm gonna get her.

And I'm gonna get the one right next to her. I'm gonna go one-by-one, but I'm gonna get 'em. And that audience was just sittin' there, and it's quite passive --it isn't really goin' crazy. So I thought "I'll do my little bit again --I'll throw a hook out." So I threw one of my cheapest runs out. I threw it at anybody, but Nat Cole picked it up and played it. I made it dumb enough so that anybody could play it, and I got Nat followin' me. So I threw a little tougher one at him. And Nat says "Hell, I can play that one" --you know, in his mind. So Nat climbs on my back for a second one. I said "All I gotta do is reel this cat in now (LAUGHTER). Got him now." So I made the next one a little tougher.

Well, everybody starts gettin' in ... . You know, they're sayin' "What the hell's goin' on here? We got somethin' goin'!" So I see this audience lighting up and I says "Now I got 'em all on the hook." So Nat doesn't know he's hooked yet. See? He's swimmin' around there thinkin' "This is duck soup. We're gonna have a lot of fun and no one's gonna get hurt" --he doesn't know he's goin' to the killing floor (LAUGHTER). So, it gets tougher, and it gets tougher. And finally I let go with a run that went all the way down that guitar, and all the way up that guitar and that I knew God Himself ain't gonna do (LAUGHTER). So Nat took his hat off and threw it on the piano, and he just stood up and looked at me, and that was it --the audience went crazy, they threw their hats in the air, and that was the climax of that first album, Jazz at the Philharmonic.

BR: This was a live performance?

LP: Yeah. Nat threw his arm around me and he says "Les," he says "that's too much." It was all a game, and the game is very simple, that is to just walk the guy out in the rings, you know, and he doesn't even know he's got his gloves on (LAUGHTER). And I know I can't play some of the things he can play, but I turn around and play 'em in a position so he's following me and he doesn't know it. And then I say "Well, I got three things in my pocket that I know that this guy, it'd kill him. I'm not gonna kill him until I got everybody in that audience with their eyes poppin' out, and then throw one at him and then just see what happens. If he possibly goes anywhere near it --which he did. If you listen to the record, he played something different than what I play. So I went back and played it again, and he went after it a second time. So the third time I give him both barrels, and he just took his hat off, threw it on the piano and he did this (GESTURES) and threw his arms around me and it just tore the show apart. It was showmanship. Nat was a great man-a great piano player, and a great singer, and a great person. I've known Nat from Chicago, and his manager was my manager, so we were closely related all through life.

PL: One thing I'm trying to do is relate the new developments in recording to the records. And I figure you can give me a very good overview there.

LP: Well, I built my recording machine back in the late '20s and then found out that Western Electric had built theirs in something like 1925 or '26 and that I was only about three years away from them. The second surprise that came to me is to find out that the dog didn't invent the phonograph --it was Edison (LAUGHTER). I had never heard of Edison, I didn't know anything at all. I knew at a very early age I'm sittin' there lookin' at my mother's phonograph, and I says "Well, if it'll play the record back, why can't I just reverse this thing around and make a record?" And I did, and my father, being in the garage business, made me a lead screw, and the first thing you know I had --with my own imagination and no concept at all. I got it from a wood lathe --the whole concept.

But as far as knowing what the other guy was doin', I hadn't been out of the woods. I didn't know that Edison existed. I didn't know how they made a record or anything else. I just had to do it on my own. I didn't go to a library or nothing. Made my first record, and when I heard myself come back, my brother said "Big deal." My brother, you know, when he threw a light on, he expected it to light --he didn't know why. 1 had to know why--I took that switch apart the first day we got electricity (LAUGHTER). I got knocked on my rear end but I found out damn quick it was 110. But in 1928, I was well on my way with my first machine, and I heard myself singin' I'll Be Comin' Around the Mountain.'

PL: Is this a lathe basically? A cutting head?

LP: No, it was a windup phonograph my mother gave me the handle on a Wednesday. I only got it one day a week.

PL: Are we talking about a cylinder now?

LP: No, it was just a flat disc. We had a Victrola, and you wind it up. Jack Mullin has one. You wind it up, and there it is. I went to Milwaukee and I bought a Western Electric playback and reproduce head, and all I did is make a steel needle for it. I put it in there, and I started cuttin' on some tinfoil. And I tried that thing, then I tried aluminum, and when I found out I could emboss, well, I just got a big, heavy lead weight and I put it on there, and I says "Wow, I can hear myself. This is great." But then I took the head off and played the thing backwards --the same thing. Then I went farther than that I jabbed it in the top of my guitar and I had electric guitar and I says "This is the way to go, I got an electric guitar now."

PL: What year was this?

LP: '28. Same thing.

PL: So you invented the electric guitar?

LP: Yeah. '27, '28, in the late '20s. By 1930 I was gone, in Chicago already.

Here's another one for you. We used to broadcast in Wisconsin, Racine, Kenosha, Milwaukee, and the engineer sat on the floor with a little crystal set, and he'd get that and he'd say "Sounds good," ... had his earphones on and he'd point to you and you'd sing and do your songs. I'd sit on a bed! We were broadcasting from a bedroom! And the amazing part about this thing is that I didn't know any different. Two hours later I was on stage at the Capitol Theater. And I had to do a show. That's the first hook I ever found. I was out on the stage and after a few minutes of me (MAKES WHISTLING NOISE), I was off stage (LAUGHTER). Yes, sir, I learned at an early age, I better learn to be a showman. I was a dead duck. I didn't last long at all.

BR: Was it amateur night?

LP: No, it wasn't amateur night --I just was at the Capitol Theater in Racine and I got the hook. And I says "Well, I'll have to learn" so I got a wig and I started doin' comedy. And by 1930 I was well on my way to doin' burlesque shows and country shows and so forth and so on.

BR: As Red Rhubarb, were you a comic character?

LP: Yes. Played the harmonica and the guitar and I sang funny songs and serious songs and .... Well, I was one of the biggest in Chicago if not the. Well, the biggest ended up Gene Autry, but in Chicago I had a tremendous following, and in about 1933 at the World's Fair I decided to drop playing the guitar and become a piano player. Because by then I was a pretty good piano player. And in 1934 Art Tatum came along. And I go down to The 3 Deuces and I heard Art Tatum and I said "Well, that ends that (LAUGHTER). There's no sense in me even lookin' at a piano." So the piano went to the side, and I went back to the guitar. But that was my first machine. The second machine I built was in Chicago. I remember building this lathe myself and finding that the turntable had to be balanced -- dynamically balanced -- and so I used plaster of Paris underneath the table. I patched it up with plaster and I got it so that it was evenly balanced. It was a rim-drive. No overhead feed-screw, like a Green Flyer which was in there too. I had a Green Flyer for the second machine. And so I had two machines, and I was doing my multiples then.

But never knowing that there were commercial machines.

PL: When did tape happen? Late '40s? 1947?

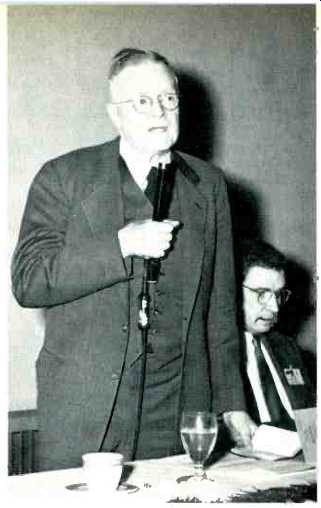

----------Col. Dick Ranger, flanked by F. Sumner Hall, at an early meeting

of the AES.

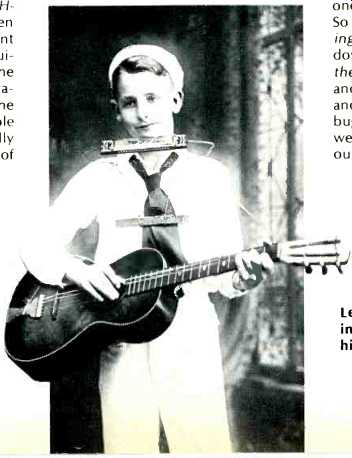

---------Les Paul, at age 11, in Waukesha, Wisc. Already his ability was

evident.

LP: The tape I heard by Col. Ranger in Newark, New Jersey, back in probably '45 or '46 --it was in that era. It was right when he came back from the war. And I happened to be workin' with Judy Garland and Paul Whiteman. And then Col. Ranger called me and asked me if I wanted to hear a tape machine. And I said "Is it anything like a wire machine?" He says "Yeah, but the wire is turned. This is flat paper tape and I brought it back from Germany." From Luxembourg or wherever he was. He brought it back in pieces and put it together in Newark. I went over there, and I heard it. I went back to California and I told everybody in California. I said "Man, Dick Ranger's got a thing that you won't believe." I'd known Jack Mullin, and Jack says "I got one in my garage. I haven't put it together yet but I got one in my garage." Col. Ranger was a lousy businessman ... and he worked for me, I hired him. So Col. Ranger worked for me for four years. In all our filming. Television in my home. But Col. Ranger being a bad businessman, Jack Mullin was a good businessman.

He wasn't much better than me, because he gave the idea --I presume he gave the idea --to have Ampex .... He walked up to this Murdamood or whatever their name was ... up in San Carlos.

BR: Alex M. Poniatoff. He was building the electric motor.

LP: That's right! Exactly! Alex is a very dear friend of mine. And he gave 'em the....

BR: Well, I don't think Jack felt that he owned it, he just copped it from the Germans.

LP: That's right! You see, during the war, I was here stationed in California, and we had to slip-disc all this stuff. So that when we got somethin' from Hitler and we didn't want him to say what he said, we would edit him. So we had three turntables, and we had our earphones on. I worked for the Armed Forces Radio Service, and my job was to edit. Only two guys workin' with three turntables, while this one's running, you slip this to this one, that one you kill and you set up that one.

So with three tables, you're there, editing. And, boy, you gotta drop it right down there, and listen and hold right there. And slip-disc on those things, and you make a one-generation down, and there you are with a speech. What bugged us is we could hear pops, and we could hear inside spaces --from outside to in --and then when we got inside, it went from inside to out. On our discs. Well, we found Hitler over there givin' speeches, and we didn't hear any pops or anything. And that son-of-a-gun would edit Roosevelt's tape, and he'd be on the air in five minutes with it. Or Churchill. And we're saying "What in the devil is he doin'? We can't slip that fast! What does he got goin'? Is he on wire?" If he's on wire, we'd hear this fidelity

drop 'cause that's gonna roll. One minute you're on the front of it, one minute you're recording on the back of it.

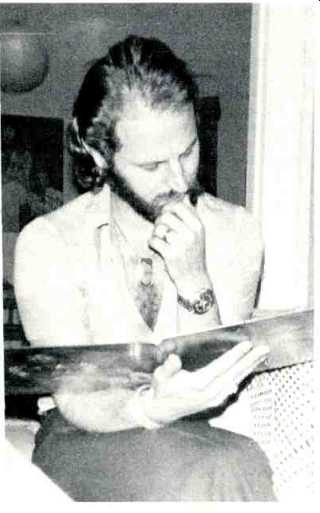

------ Eddie Kramer, currently a leading producer, benefitted from

Paul's innovations.

So we were really befuddled with this German job, you know? When we got our hands on that German thing, hell broke loose. So in '48 unfortunately I tipped a car over, and I was in the hospital for a year and a half.

And that year and a half I was at the Good Samaritan here, with my arm in a cast, dyin' to get my hands on a tape machine. Because now I could see where I could travel--you're not gonna travel with two lathes in a station wagon. Where with a tape machine, you could. And I had it all figured out on an envelope as to how you could do sound-on-sound --you can do this all on one machine. No VU, no speaker; all I had was a pair of earphones and a microphone, the guitar, and a little mixer. A little box.

PL: And so you developed sound-on -sound? And this was '48?

LP: Umm hmm.

PL: And how about Emery Cook and his binaural recording? Was he the first guy to do more than one track simultaneously?

LP: I think he was, it was in that era. I didn't watch it quite that closely. Emery Cook I was very aware of, let's put it that way.

BR: Cook was doing discs with two' separate cutting heads, and then he played it with two ... Cook's still alive and well incidentally.

LP: He's up in ... where is he? Massachusetts or somewhere.

PL: Tom Dowd described him as a "wild-haired genius who fancied doing raucous things."

LP: He was a guy I kept my eye on, and from out here we were watching him quite closely. The problem was nobody could get a playback arm that could reproduce what we could put on the record. Now I went to old Pop Olson who lived out on the beach, went fishin' all the time. And I finally got him to make me a pair of heads.

And I said "I want these cutter heads to go to 12.5 kHz --clean. Right to 12.5. Well, he said "Mine only go to 8," and I said "Well, I'd like to get 'em to 12.5," and he said "Well, if you've got the patience to wait, I'll work on it until I get it. I have to get a different kind of rubber for the damping and so forth" and I said "All right." So he did.

And he got the things out there to almost 12.5 and then we found that if we rewound 'em, then we could get 'em out there. Now we got the heads there, and we got the light pattern, and we're lookin' at the thing, and it's on the record. With an oscillator. So we know that we're goin' out there at 12.5, and we know the music is clean.

But playin' it back was with a 9A cutter and a playback arm, it was atrocious.

Later on you get the 7,000 cycles, and we took a nosedive and it was bad news. So in about 1945, '46 --somewhere in that era --along came a friend of mine. He said his brother worked in Schenectady or wherever it was for G.E. And he pulled out of a bag six pickups. And he handed 'em to me, "They're no good to me. You want 'em?" And I says "What are they?" He says "They're pickups of some kind." So we try the pickup. And the pickup was a high-impedance pickup, and we said "Gee, if we run it .... Let's try rewinding this thing down 250 ohms and see what we got." And we got that kid to go all the way out to 15,000 cycles.

BR: Were these the ones with the double stylus that you push the button in the top and turn it around?

LP: No, before that, before that. I got the original tomato cans home. So these two--we call 'em "tomato cans"--we got a pair of those goin', and the first thing you had to do was remove the four bolts that hold the turntable down because they were magnetic. Can't have any magnetic bolts or anything around it or it'll go "tuck tuck tuck tuck" you know. So, we got the tomato cans to go, and we got a flat response to 15 k and we got the cutter to 121/2 k so we had that goin'. And that's when Fairchild came into the picture, and he actually built a replica of the garage on Curson and Sunset. He come out here with his crew --flew the whole crew out--they measured the garage off, and copied it. Then they went to the guy that built the head, copied that, and they copied the amplifier. But they made some fatal mistake. First of all, they didn't get the original head. They got the head that was the old head, with the big bumpers on the side. Olson wouldn't sell 'em the new heads, he sold 'em the old head, the one he'd tossed out. Just one. The second mistake that Fairchild made is he went to the 807s because he could get more power out of the heavier amplifier, and use four of 'em push-pull. Instead of my little ding-a-ling job. And probably many other mistakes that he made that I don't know about. I'm sure in his drive mechanisms he copied my disc machine. The disc machine was made with Wally Heider. Where his studio was, was a hobby shop, and for $10, I rented that hobby shop. We could go in there after 10:00 at night and stay there all night and work. And we built this machine, little by little. Another friend of mine, who died, Lloyd, and built this thing with the lathes. We cut out all this stuff, and we made the turntables and the feed screw and everything else, and as we built this thing, we had to put it somewhere, so we put it in the window. So the engineers for Arcturus Engineering happened to be walkin' by this window, saw this machine in there, walked in, and said "What is that?" "I don't know --two kids rentin' this place at night are building somethin'. I don't know what they're building .... " So they got my phone number and they called me; they said "What is that?" and I says "That's gonna be a recording lathe." And he says "Well . . . . what percentage would you want for it?" "Do you have it copyrighted?" And I says "Nah, we just built this thing." "Tell you what --if you build us one .... First one you build, give to us ...." "It's yours. Take it." So they copied. Like I say, there's 1500 of 'em out here. You'll see 'em at KHJ, you'll see 'em at Radio Recorders .... You'll probably see 'em everywhere.

BR: Does Bill Robinson have one?

LP: Probably Bill has one. It's a well-known cheapie tape machine that we built up. It worked perfect. With those dental belts, I was doctor to White because during the war you couldn't get dental belts. So I just said "Dr. Paul" to S.S. White, and says "My belts are shot and I need some new belts" and, being a doctor, I got the things right away (LAUGHTER). So I got these things and some beeswax ... Here is a funny story --very short, but very funny. We got down to fixin' the speed.

And I says "I want three speeds; 33, 78, and one right in the middle 'cause I want to vary the speed and do these multiples at different speeds." Happened to be 45. Damdest accident ever happened in my life! Happened to be in between and it happened to be 45. No reason --could have been 40. So we look in the phonebook --in the Yellow Pages --and I'm wondering if the guy is in there yet. So we run our finger down there and we see "cutting lathes" for doing this work that we wanted done ... cutting the pulleys. Goodspeed, it was. I said "That's our man." And he's in Glendale. So we go there and the guy says "What do you want?" and we brought the whole lathe in this Model A Ford to him. Laid it down there on this floor and he says "What do you want?" and we say "One between 78 and 33. We got a strobe here, we can show you." We wanted something in between there--halfway in between there.

And the guy says "Well, can you guys go to a movie or somethin' and come back in an hour? I'll have it done." So my friend says to me "That'll be the day." Come back, it was dead on when they put the strobe on it ... He didn't even use a strobe. He said "Take the strobe with you. I don't need it." He figured it out, you know? He says "What kind of groove --you want a round groove, you want a V-groove, what kind of groove do you want?" "I want a V-groove." "You got it." Goodspeed was the man that put the lathe on speed, but the dynamically balanced flywheel, that's Cadillac Flywheels. I started that thing and I says "You know, that's gonna be one hell of a job to get this thing perfectly balanced." Here's how it happened: The guy's name was King. And this fellow trained the dog for "The Thin Man." And he said "My dog can talk. And I want to record him" (LAUGHTER). A talking dog! A talking dog is all I need now! I've had Pat O'Brien, the Andrews Sisters, you know, W.C. Fields --I've had everybody in my backyard. Art Tatum, Andre Previn .. and a talking dog, man. So this little guy comes in here, Mr. King, and he sees me building this machine. I had taken two 16-inch discs, and cut a piece of plywood 16 inches and glued 'em together. That was my turntable.

Well, that was a pretty crummy turntable, I want to tell you, but I still got it.

So he says to me "You know, you need something more rugged than that, something that when it gets up to speed ... you may want to put a governor on that thing --you know, that wig-wags underneath there. With the springs on 'em" and I says "jeez, that's complicated, and I don't want to go that way." So he says "Well, there's somethin' dynamically about .... " He says "What about a flywheel?" Well, we were out the door so fast, we were down to the junkyard in a minute, asking "What do you want for a flywheel?" Only wanted a buck or whatever. Come back and you can't beat that, those guys spent years to get that correct, right? There you are! It was that simple. Happened in '42.

Then in 1949, sound on sound happened, and once when Bing Crosby was in our backyard, I went to Bing and I said "Bing, you're close to Ampex. I gotta have a tape machine.

We're doing a show every Friday night on KFI--on NBC--and it was 'Les Paul and Mary Ford at Home'. " And I said "This show, I gotta do travelling, may be in Terre Haute, but I gotta do this show. And I gotta have a way. If I can get a hold of this tape machine ...." So the idea one day came to me, the idea would be to add a fourth head to the thing. That would solve the problem.

PL: We're talking about Sel-Sync?

LP: No, we're talking sound-on-sound. Sel-Sync didn't come in until '52.

That's when you're listening off the record head when you're in the record mode.

PL: But who was the first person to be involved with more than one track on

a tape machine? Was that you, and when was that?

LP: That was me, '52. That was the first of what we call Sel-Sync, where you can overdub--you're into that status.

There probably was such things as stereo and so forth on the horizon. Stereo is nothing new, it just wasn't accepted or ready.

BR: Western Electric developed stereo in the early '30s. They had 3-channel stereo that was better than the later stereo.

LP: Oh, it was here. In '52, no one ever said the word "stereo." It was 1948 and I got a call from Mt. Vernon.

"Consumer's Report" --"Consumer's Research" it was called at that time.

And they wanted to know if the word "high fidelity" would be offensive to use in the first record review. And they wanted to use Lover as the standard of the industry, to check their equipment. And if Lover sounded right on their equipment, then it was cool.

PL: So you'd place overdubbing and Sel-Sync and multitrack --multitrack meaning more than one track --all in 1952.

------ Tom Dowd, another producer who benefitted from Paul's ideas.

LP: Right. 1952, and it was 1956 before we'd completely wedded the console which was built way ahead of the 8-track ... there was Rein Narma, who was vice president or president of General Instrument Company now.

Preceding that he was vice president of Ampex, preceding that he was vice president of Fairchild, but preceding that, he worked for me. The other man was Bob Flint, who is now the chief engineer of Black Company, ahead of that Addressograph I believe is the name of it. He was chief engineer of Ampex, ahead of that he was at Fairchild and ahead of that he worked for me.

The engineers that have come out of my little company --my little haven back there --are outrageous. If you look at "The Hindenburg Disaster," if you look at "Earthquake," if you look at "The Towering Inferno," if you look at "Kojak," that's all an engineer that grew up and learned engineering from me. That's John Mack. He's at Universal, and he was my engineer. Col. Ranger worked for me. Now if you want to go further than that, Rein Narma worked for me, Harry Mearns, chief engineer, RCA, no, maintenance engineer --chief of the maintenance department. Ah, if you want to take my brother-in-law Wally Kaman for 10 years did nothin' but edit for Bill Putnam --he was the man at Western and United Records. Did you know Wally?

BR: I know his name.

LP: Wally Kaman? I handed him a piece of tape and told him to edit it and I think he drank a half a bottle of bourbon --just scared him to death! You see, the great part about the early days was we had no fear because we didn't know what to fear. We didn't know what it was all about. So we just went in there and did it. There wasn't anybody to say "can't do it" because they didn't know what they were talkin' about and we didn't know either.

You know, who thought of a patch bay? --you just solder it on, that's all. I had a lump of solder big as a golf ball on there! (LAUGHTER)

PL: And how long was it till stereo filtered down to the public?

LP: We were designed for stereo unknowingly. We had everything for stereo, there has never been a thing changed on my board from 1954 till now. It's exactly as it was, and it has all the provisions that you have now. Not as many knobs as you've got now. I had a choice of slider faders or knobs and I picked knobs. It was just a matter of choice. I says "Spread 'em out, I got big hands." I says "I'm in no hurry.

And I only want eight tracks." There's four on the low-level mixer --on the side --and eight across, and I got all the equalizers under the sun. Which I never use, but they're there. And I only do that when I rescue some guy that got in trouble (LAUGHTER). If do a date, I don't go into the 8-track --go right to the 2-track. But the machine was built with a left and a right. And a center.

PL: 1 understand 3-track and 4-track came in pretty simultaneously.

LP: They come in right on top of that 8-track. Well, the 8-track, when it came out, say '56, the 8-track took out.

It was a sleepin' dog, and so was the 4-track ... and the 3-track. Three-track came out faster, because it was used in filming. So 3-track was an idea that came from filming, so that came about, and that was a dog, and had a lot of things that had to be redone. So that's when I called Poniatoff and told him that when he goes to work he's gonna find a pigeon sittin' on the Ampex on his front lawn. He said "You wouldn't do that to me." I says "I already did it. That son-of-a-gun is on your front lawn." He says "Did you put a lemon on it?" I says "No, I did everything but. You got that darn thing until you fix it. It's full of garbage." And he laughed. He says "Well, we'll fix it, we'll get the best engineers on it." I met one of the engineers the other night who said "they sat up all night workin' on it until they got the noise out of it.

But that didn't come in until the later years. The 3-track came in first, then the 4-track came in, and I guess the guys that really got their hands on it was The Beatles. The Beatles did all their stuff on 4-track I understand, and did an excellent job with Sgt. Pepper.

That was a hell of an album.

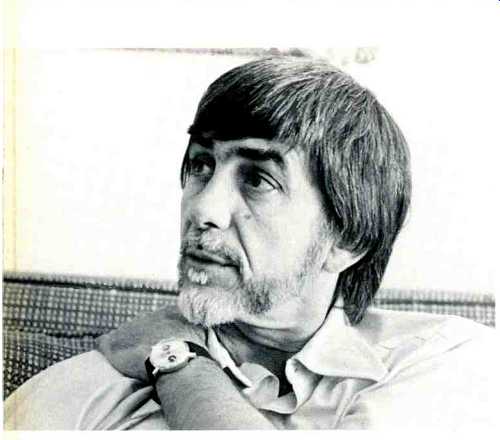

-------- Paul with son Robert on drums.

I think it was more 3s than 4s when it started. Our Ampex, that we got --we had to ship it back three times, that 8-track, because the first time they sent it at 30/60. Instead of 15/30. If we stood near it, we could get killed! (LAUGHTER) Then the EQ was wrong, then they didn't have a master bias oscillator and, naturally being in the experimental stage, there was no head lifters and there was a lot of things that were wrong with it. The signal-to-noise was high, and there were many things ... crosstalk and so forth and so on. That's where Col. Ranger came into the picture, and Rein Narma. I'm amazed that so many people ... have kind of forgotten Narma, because he's in the marketing department at General Instruments --probably one of the most brilliant men that I've ever had the pleasure of working with. He was captured by the Russians, he was captured by the Germans, captured by the Americans (LAUGHTER), and he's from Estonia. He's a man that says "What's your problem?" and when you tell him the problem, he says "Well, I know of three answers right off." He never looked negative, he was a guy that always left his suitcase, his rubbers, or his kid at my house (LAUGHTER) and went home and then would call me and say "Have you seen a kid runnin' around there? It's mine." He was a real scientist --x --minded professor. The guy would walk in and I would say "I want so-and-so" and he'd write it out on a piece of paper and give it to one of my engineers and say "Go build it." And it was dead on. We'd make bets --four engineers would stand there makin' bets. John Mack, who did "The Hindenburg Disaster," "The Towering Inferno," and all that made a bet with a couple three other engineers of mine, and Johnny Hilliard was there too. We all made a bet that Rein would blow ithe couldn't be that close. And Rein said he'd be within an eighth of a dB.

BR: Is Dick Stumpf part of your circle, out at Universal?

LP: No, no. No, just John Mack--I got John Mack out here. He was with Rank over in England and came to America, I was short an engineer and I said "Anybody in here got an ear for music?" John Mack raised his hand and says (ENGLISH ACCENT) "I'd like to try. If you give me a chance." And I said "I'll give ya a chance. Come on in here" and when we were done makin' our films, around 1959, he said "Les, do you know anybody out in California?" I said "I'll getcha a job on me. I know everybody in California. He came out here, he worked his way from the bottom all the way to the top, and he's extremely happy. I'm very proud of him, and he's one of my many ... They're like children to me.

My son is a head at Atlantic --you go down to MCI and say "Gene Paul" and they say "That's your son? He's the king! The king." I'm very proud, very proud of my son.

He came to me one time, and he said "I got a problem at Atlantic. A tough problem." I says "There's no problem, kid." He says "Well, they're only gonna have seven fiddles and they want to make it into a whole string section. What should I do?" I says "Well, you set up the chairs for the whole bunch. And you put the mikes up for the whole bunch. And turn all the mikes on. And put the guys in the first row and have 'em play, and then have 'em move back to the second row and play there, and then move back to the third row and play there, and play all the way back, and you got yourself . . . (LAUGHTER)." Then he walked out of there, and I walked up to Atlantic one day, and Tom Dowd come to me and he says "That kid of yours is a genius! (LAUGHTER)." I says "He sure is.

That's the sharpest kid you'll ever find." I'll tell you the one that really threw Gene though. I walked up to Atlantic one day and Ertegun was in there, everybody was in there, and they're doin' whoever it was they were doin', a big date in there. I walked in and I wasn't there two seconds and I says "You got that piano out of phase for any reason?" And everybody jumped up like they were standing at attention for the general. And my son says "Is it out of phase?" I says "Yep" and turned around and walked out. And a guy walked out with me, he says "You sure shook hell out of your son. What a joke." I says "It was no joke; it was out of phase." He said "It was?" I says "Yeah." So my son come out in a few minutes, and he says "You know what, Pop? It was out of phase." I says "I know it was out of phase."

PL: What did you hear?

LP: Oh, I hear it, I hear it. Once I went to the Mayo Clinic for these ear operations, and they rebuilt me an ear.

Mayo Clinic said "We're gonna put a hole in your ear that's so small water won't go through it but we can get this high-powered microscope and see if there's any granulation or any liquid behind it." And I says "Okay." After a couple of days, I went back there, and the doctor says "U h, how's your hearing?" I says "Lousy." And he says "Well, what's it like?" and I says "Well, its down 40 dB at 125 cycles." He says "It's what? That's impossible." And I says "I can tell, just right like that." Guy called in the other doctors.

There's all these doctors comin' through and they get ready to run another test and put it right over the top of the other test, in another pencil, red pencil. So I says "Well, 'fore we make this test, what is the bet?" and he says "Well, you got the Mayo Clinic free it you win. If you lose you pay for it (LAUGHTER)." I says to myself, "I can't lose on that deal." And if I go up there now and if I announce my name, I'm the next one in. I mean I don't gel no bills. And they said "Can we put it in a medical journal?" I said "You can put it anywhere you want." He says "We must have been gettin' up and drivin' a hayrack!." I said "I know what you're gettin' but my ear is so tuned to what I'm hearing, that I know if it's 6 dB, 8 dB, 4 dB, and at what frequency I'm hearing what ...." And I was on the operating table, and during the middle of an operation the guy takes a tuning fork and hits it and asks me what key it's in. Right? So I named it and the guy says "You're right." I says "This is the damndest thing I ever heard. Here you're choppin' my head up, and you want to know what key I hear!"

BR: I was waiting for the story you said you were gonna tell about lazzbo Collins .... and his ball of string.

LP: Oh, the ball of string! Well, I'm goin' overseas, and I'm over Alaska in the lounge and this guy comes up to me and he says "You know, I'm an engineer with so-and-so." He don't know who I am, I don't know who he is. I'm listening to him talk and he asked me what business I was in. I had to think of a business, so I said "I'm in the garment business." And I don't know where I picked that up. Just then a woman wanted to get in the bathroom. So I ask her if she had a dime, and she digs in her pocket lookin' for a dime and I said "I was only kiddin'. You can get in for nothin' here." The guy says "Hey, that's a good-lookin' chick." And I says "Watch it, that's my wife." I never seen that gal before.

"Oh," he says, "I'm sorry." I said, "Don't feel sorry about it because we're breakin' up. This is our final trip to get over it --gonna try and cement it up but "we'll never make it." He says "That's a shame. Look, you're a perfect matched pair here, you know (LAUGHTER). I says, "Never make it." She's too far out for me." He says "What's the matter with her?" and I says "Well, she saves string.

(LAUGHTER)." "She does what?""She saves string." He says, "So? What's so bad about that?" I says "I didn't mind it when it was a little ball. But when it got so big that I had to cut a hole in the apartment ....'cause the ball got so big .... (LAUGHTER)." When you pack a lunch every Sunday and take a flashlight to check the knots! I'm living with a ball of string in my house and "this string is gettin' out of hand --every time she sees a piece of string she picks it up and adds it on to this ball (LAUGHTER), and I can't take it anymore." And he says "Well, when she comes out, can I talk to her?" I said "Sure (LAUGHTER)." And when she comes out, they're tryin' to talk her out of this ball of string, and she's lookin' at 'em dumbfounded (LAUGHTER) . And another guy's talkin' to me saying "Look, a ball of string isn't the end of the world. You can always put the ball of string in a separate room (LAUGHTER)." And this went on all the way to japan . . . . And I guess about the second and third place I played, I walked out on that stage and they says "Here he is, Les Paul" and I walked out and right in the front row is this guy (LAUGHTER). And he says "Have I been had! Boy" he says, "did I get sucked in on that story." You know I tell these stories like now and there was one where I went to Brazil and we didn't want to be known. We were there early and I said "I want to see Brazil without being bugged with a lot of things and people." I said "I'd like to go in there with a pair of Levis, walk down the street and see what Brazil's all about." So I registered in as Lester Polefuss.

Come down in the lobby and the guy said "You Lester Polefuss?" I says "Yeah." He says "Can I speak to Mary Fordus? (LAUGHTER)" I went to get the Grammy award and I registered in as Lester Polefuss and I'm there a week before the Grammys. One day this lady said "I'm dyin' to tell you who you are (LAUGHTER)." She just says to me "Mr. Polefuss, I'm dyin' to tell you who you are." Then she starts hummin' How High the Moon and I'm thinkin' "I don't believe it." One of the funniest lines --"I'm dyin' to tell you who you are." I couldn't believe it!

PL: Les, do you remember the first record you were ever on that was commercially available? Was it a single?

LP: It was a hit. It was called lust Because. Made in 1930, for Montgomery Ward.

BR: Was this the one that goes "lust because you're a da da da..."?

LP: No. "Just because you think your hair is so curly / Just because you think you're so hot / Just because you think you've got something / That nobody else has got." Oh, it was a big hit.

PL: So you were the artist --as "Les Paul"?

LP: "Rhubarb Red." I made $20 (LAUGHTER) . And it took about four, five years for it to be a hit.

PL: And what was the label there, do you remember?

LP: Champion, I believe. I think it was Champion. I do not have that record, but it was made on gravity feed. A gravity-feed recorder.

PL: I don't know what that means.

LP: Well, you just write down "gravity feed" and there'll be a lot of questions asked. But that means it's got a weight, and it goes toward the ground at the speed of gravity and that's what makes your turntable go at 78 rpm. And that's a beaut. And then you crank it up and start all over when it his the floor. It's a counterweight. It's non-electric. You crank it up to lift the weight up but that's it. And the VU meters...I'll never forget the early VU meters. You say "Hello" and that needle'll start to move (LAUGHTER), and about two minutes later it says "Hello." It goes like that (DEMONSTRATES), that meter. The damping on that meter was unbelievable--guy says "Watch the meter." I says "You gotta be jokin'. I'll be half done with the number by the time that meter moves!"

PL: You sang and played guitar on this record?

LP: Yes, and harmonica. The other side of that was Deep Elm Blue $ and that was a hit too.

PL: Les, you mentioned some nonstandard-speed recording, as double-speed guitar, say? When did you first do that?

LP: Well, that came about in '46.

PL: And so were you the first to do that--to playback...

LP: Yes. As far as I know.

PL: How about backwards recording?

LP: Oh, sure. Meredith Wilson was the one that brought it to my attention.

That didn't happen until maybe 1947, when I made the records for Capitol I found out that you better make 'em backwards because of the transient response, and when you start goin' up there double-speed, and you're laying that's crazy. You're gonna break the mike." I says "I haven't broken a mike yet. Everything is fine." "Well, you're gonna pop the Ps," they said. I says "Then let 'em say B instead of P." And it wasn't long before I had to put two mikes up and told 'em to sing in that mike and I recorded on the close mike.

So this guy is singin' like mad right into this distant one and the one right next to him is the one that I'm really getting him with. So I would get him, I would fool this guy. We'd put a pencil right across the center of that microphone so he wouldn't pop his Ps.

PL: What was the close mike for in this case?

LP: The close miking essentially was because there was noise in my amplifier, because I was a low-level mixer.

That's what I had, a low-level mixer. A low level means that you are controlling with a T-pad before, from the microphone looking into the preamp. In every console you look at today, your volume is controlled after the preamplifier. So you've already cremated the amplifier. You're going to go like that (CLAPS HANDS), and you've killed it.

PL: We're talking about distortion?

LP: We're talkin' about distortion.

We're talkin' about you cannot overload anything that's got a pot hangin' right in front of the microphone, right there before it ever gets to the preamp.

So I had the cleanest records that ever came out. So when the piano player went up and hit one of the big chords. . . Like I played last night, you're hearing these tremendous sounds come off an acetate, where everybody says "My God, what in the world is happening? Why?" And it was a very simple thing --I had to close-mike.

Because if I backed the guy that far away, you got so much noise, you couldn't believe it. So I had to bring the guy right up tight in here, when I brought him tight in, a second thing happened. You should never put a resistive load across a microphone. If you do, you change the response. But nobody found out that the response is to your advantage. That it took the bass out of the 44. So, with the 44, as you moved in, the bass built up. But when you put a resistor across it, it took the bass out. So by accident, found out that by leaving the T-pad in there, you move the guy right into the microphone and you have the same thing as you did if it wasn't in there and you're three feet away.

PL: But weren't the vocals always recorded fairly close? Even in the Big Band Era?

LP: In the Big Band Era, they may have got that close (DEMONSTRATES), but you never walked right up to the mike.

You never got right where you had lipstick on the mike, no.

PL: So you were the first to close-mike instruments, anyway.

LP: Yes. When you get a violin, and the bow is just runnin' right straight across that microphone, when, you get a trombone with the microphone in the bell, with a Saltshaker --or a whatever --you say, "This is ridiculous." And I've had many a guy from MGM say "I won't record in that room.

I just came from Republic Sound Stage, and if you think I'm goin' in that dumb garage and play one inch from a microphone, you're crazy." So I'd say to the musician "Would you mind playin' a couple of notes, come in and hear it yourself and then make up your decision whether you'll record in my studio or not?" One guy was hired on a date, and he says "I don't care how much you pay me. A microphone should be that far away." Now that's the way he was brought up. So the microphone'II be over there where those lamps are; this is the way he's used to recording a string quartet, and he just doesn't... And this was the industry --the standards of the industry. It was not to chuck a mike down your throat. Bing Crosby was the first one to say "I never heard sound like this in my life. The guy swallowed the mike." He says "This is ... ridiculous.

It's the greatest sound I ever heard in my life. That guy, you can hear him breathe. You hear every sound in his voice." You see, this is because you're capturing everything you want to capture. If you don't want to capture it, don't.

PL: So when was it that you first close miked the instruments? What year?

LP: I close miked right from the beginning. So that goes back to '42. Starts right from the time that I built the mixer and the whole thing....

BR: This overpowered the noise in your amplifier.

LP: That was the basic idea, 'cause without it I was in trouble (LAUGHTER). More accidents happened in my lifetime that turned out to be ... some of the greatest things that ever happened in my life were just necessities.

In fact, all of 'em were. necessities.

BR: How do you feel about playing through an amplifier into a microphone versus playing from a pickup right into the board?

LP: Well, now there's a good question.

Now you may find that going direct into the board is a direct sound, an intimate sound. It's as close as you can get; you can't get no closer than direct.

Direct, I happen to prefer because it's so pleasant, and you can do so much with it. But many times I'll place a microphone as much as across the room. And pick up a speaker. And multi that kid. I won't do it with their funny boxes. I have a lot of funny boxes, but I don't do it that way. I do it the correct way, where you take a multi off the preamp, feed it out there, feed it into a speaker, take that speaker and put that microphone over there at a distance.

Jimi Hendrix called me one day and asked me, how he would do it? How he should do it? And I said "That's the way I would do it."

PL: It was direct and distant miked?

LP: Direct and distant miked. And now the distance of the miking is up to him because there is a certain sound that you get out of this non-linear string, non-linear pickup, non-linear guitar--okay? --coming out of a non-linear speaker, out of the wrong box, out of a wrong guitar, but they sound great, so that these two wrongs make a right.

And this sound that he gets out of this dumb speaker and this dumb guitar turn out to be great. And he wants that sound.

PL: Well, Eddie Kramer used direct and distant and close miked all the time.

LP: Eddie Kramer did it, was working for Jimi Hendrix --that was at the Electric Lady, that's where it happened. He was the guy who'd asked me. This is where it came about. So when you're saying Eddie Kramer, you're talking about Eddie Kramer worked for the Electric Lady and Electric Lady was owned by Jimi Hendrix and Jimi Hendrix was the guy that called me. And he says "Hey, I wanna get that real raunchy fuzzy dirty down, you know, that."

PL: Probably "big" sound.

LP: Yeah, that real big sound. You know, the Led Zeppelin came in there later on with ... doin' a similar thing to that, with Jimmy Page and the bunch of guys there, you know.

PL: More guitar effects-oriented here.

How about tremolo? When did that first start happening? LP Well, tremelo .... Where did the tremolo come from?

PL: Was it on an amp, first of all, or was it a separate unit?

LP: Yes, it was on an amp. No, it was not on an amp. The first tremolo was mercury, in a little tube, and it used to jiggle with the motor. You turn the motor on, and it would jiggle and would change the amplitude. And it was strictly amplitude and not vibrato--vibrolo. It was a change in amplitude, and it was on a motor. This was just before ... it was back in the '40s somewhere.

PL: How about phasing?

LP: Oh, phasing came in, and it came from a guy out here in California. My phasing came about by puttin' two discs on at the same time and getting 'em out of phase.

PL: Are we talking about a shift now or just ...?

LP: It's shifting, it's shifting in and out.

I was in the army and I was listening to Tokyo Rose. She was on every day and that's how I used to hear my records in the Armed Forces Radio Service.

And the station would go in and out of phase, because, you know, overseas. So you'd have this shifting ...

BR: lust from the fading pattern.

LP: From the pattern. And my little son, who is now the #1 engineer at Atlantic --and his brother --they used to come in and say "Can I change the radio, daddy? " and I'd say "Okay." And I'd become fascinated to see what stations they'd pick. And they didn't pick a station with music they picked the station that was out of phase. And this intrigued 'em. I looked at the kids and I says "You know, it must be commercial (LAUGHTER). It must be commercial." So I says "How am I gonna do this?" You know what I'm gonna do? I'm gonna put two records on ... just let two records go --get 'em right together --and see if they would cancel each other out. And they would cancel each other out, and I put on a Variac. I just put a Variac on it --I'd bring it in and I'd bring it out, and I started to get this shifting back and forth.

PL: And about when was this?

LP: Oh, that was somewhere in '46, maybe '45, or somethin' like that.

PL: And did you use this for selected instruments on your records?

LP: Oh, sure. Used it with Mary a lot, and I used it because there'd be a lot of voices goin' here and there and we'd use it on the guitars.

PL: When did people start limiting? Limiting and compressing?

LP: The limiting came about in Atlantic City, when Jim Conklin at Columbia Records says to me "You have turned the world upside down. Columbia Records is goin' crazy. We had a meeting the other day and your ears must have been burning." Columbia had their convention at the same time Mary and I were playin' Atlantic City. And he says "Les, what you're doing on a phonograph record, we've got to do with Frankie Laine, with other people. And we can't do it, because they got one note at zero on the meter and the next that don't move it at all." He says "Everything you play, that needle stands still." I says "It's simple for me because I'm my own limiter." I didn't know the word "limiter" then --but I says "I do my own balancing, controlling by playing the guitar. I'm looking' right at a meter. And when Mary sings she's lookin' at the meter. I'm watching that meter all the time so that I don't overshoot or undershoot --that I keep the level up. I pick softer, I pick louder." So the limiter came about in the '50s late '50s, 'bout '58 --something like that.

PL: Can you restate here one aspect of your philosophy on recording --the feeling over technical perfection?

LP: Well, I think that they're getting to a point of demanding more and more and more .... I'm judging this from my sons as engineers, and others that are engineers close to me that grew up same age as my son --all of the people surrounding me. The longer they're in the business, they have a tendency to simplify. They find there's no reason just because that knob is there to use it.

BR: Well, I think that Paul is referring to is something you said earlier, when you said if you have a choice between technical excellence and feeling, go for feeling every time.

LP: Every time. If that's what you mean, yes, yes. The feeling is so much more important than it is to be an excellent .... Perfection is a disease, and it's something that .... Be aware if you happen to be of my nature. Anybody that happens to be a person that wants something as close to perfect as you can get --and that is dealing with frequency response and distortion and so on, tape machine, and slowing down the tempo and so forth and so on --you gotta be careful, 'cause you can lose your perspective quickly with one glass of beer. You can go out and come back an hour later and say "I can't believe what I just thought was good." And you've only had a dinner, a couple beers and come back. And you know when I see 'em doing all this automation ... I say "They're gonna hate themselves in the morning.

Tomorrow's another day." I'll be darned, I can't help but think of my son --he made Killing Me Softly. And he brought a test over to my house. And listened to it and I says "Well, you blew it there" and he says "Yeah, well, I'll correct that tomorrow.

And I says "Well, that. . .that over there" ... you should have done that" and he says "Yeah, you're right --that's not too slick there." He got back the next morning, they were pressing it already! (LAUGHTER). And he won the Grammy on it! He won the Grammy! Did Tommy Dowd tell you that? PL: No, but I know that sort of thing does go on --you'd better watch your mixes or. ..they'll make a record out of it.

LP: The feeling was there. You see.

Now, you get guys that are doin' all this stuff... and I pull back. They say "What's the matter, Pop, aren't you with it?" And it's hard to screw my head onto their body. Very difficult.

And they may be right, I may be right.... Lot of times they'll say "Well, now you gotta look into what's happening now." Like I jokingly said "If you oversleep one hour, you're out of the ballgame." Because today is moving so fast. If you oversleep one hour, you are now out of the business. You are out of track with the whole field and it's a lost game. So when you look at just that new automated board down there... that's the top of the board.

To run the top of that board is one man. Now, there has to be a man that can go underneath that board --that's another man. There has to be another man that built that board. Or men.

The three of 'em. Now there's a producer sittin' over there, and there's an arranger sittin' next to him. Then there's the performer. And then there's the angel --the guy that says it ain't commercial. And usually that cat is sittin' there like the sultan, and he's listening to this thing and he's saying "Get rid of it. It won't sell." So there's a lot of facets to this thing. The top of that board is fantastic all by itself. And it's not like the old days where if it doesn't run right, you lift up, you go inside, and you fix it yourself. As I told my kids many years ago, I said "If I ever catch you kids with your hands in that board, I'll kill you. Stay out of it. You're an audio engineer and remember don't go under that board. Because it's frightening what's under there." It's another world. There's few... Tommy Dowd is one of 'em that can go under the board and on top of the board .... would venture to say that Bill Robinson's not very anxious to go on top of today's board. And me, I can't cancel out many years of goin' on top of that board except for my own study. So when I go on top of that board, it's very simple. If I do Benny Goodman tomorrow, it's gonna' be very simple. I do Crosby. . . Crosby actually said "How're you gonna make the next record?" I said "Simple. With no mixer.

No nothin'. I'm gettin' an AG-440 and I bring the guys up. We do it in your living room. I take the tape under my arm and kiss you goodbye. That's it." "Hey," he says, "that's something. But I said "Nothing. Nothing! Don't need no engineers, don't need nothing. Just four mikes, four tracks, four people.

The guitar player and bass plug in, go.

That's it, that's the end. Bing sings, we talk, we do our thing, gone."

==============

(Source: Audio magazine, Dec. 1978)

Also see: Interview with George Martin (May 1978)

= = = =