Not content to have improved the sound quality of theaters throughout the world and to have wrought a minor revolution in home theater acoustics, the THX Division of Lucasfilm, Ltd., has embarked on a mission to do something similar for DVD video. Actually, Lucasfilm has been involved in the recording end of this process for some time through its THX Digital Mastering program. This operation monitors the transfer of film to DVD and certifies the software re lease as being of THX caliber. (For the record, the first THX-certified DVD release was Twister in 1997.) Now, however, Lucasfilm wants to go beyond that and get into home DVD player certification.

I visited Lucasfilm THX in late April to get the lowdown on this new program and to observe, firsthand, the technical deficiencies to which the THX group has found DVD players prone—and which, needless to say, are absent from THX-certified players. I also wangled a THX DVD Test Disc from them and (with much more difficulty) twisted their arm into sending me Version 0.98 of the “THX DVD Player Specifications,” which was specifically “Edited for Edward J. Foster (Don’t I feel proud!)

The editing seems to have shrunk the original manuscript from 50 pages to 30, with the deletions consisting mainly of the numerical technical specifications that Lucasfilm considers proprietary information. That’s perhaps understandable, as several years of the company’s time and consider able expense went into developing them. However, you will have to forgive me if I am not always as specific as you (or I) would like. I can speak of the kinds of things that Lucasfilm looks at for THX certification, but I can’t reveal the magic numbers that catapult a player into the realm of The Blessed. Nonetheless, what Lucasfilm is doing is of enough significance that I think even the outline of it is worth understanding.

To start with, Home THX certification of a DVD player involves more than merely meeting certain minimum levels of video performance. Lucasfilm says it also requires that the player meet specified standards regarding audio performance, ease of use, and reliability. Speaking from experience, I can say that the last of these three is difficult to ensure by testing just a few samples of a product. (That’s why I don’t try to address it in reviews.) Although obvious problem areas might reveal themselves in the brief time one has a component under test, long- term reliability simply can’t be predicted from short-term performance, with or without visual inspection of the so-called “build quality” of which some (especially British) reviewers are so enamored. To be scientifically justified, predicted reliability should be based on a calculation of the “mean time to failure” (MTF) of the device from the MTFs of its components. That’s no simple task and is seldom done for other than military or space-bound gear. Many consumer-grade parts have no rated MTF in any event.

Backing through the THX list, we come to ease of use. This is a terrific idea. DVD players are relatively complicated to operate and, especially, set up, which means that they are likely to be set up and operated wrongly! Anything that makes the use of a player more intuitive is great in my book. Of course, what’s intuitive to me may not be to you, so who’s to say what is intuitive and what is not?

Unfazed, Lucasfilm has braved the surf with a certification specification that contains user-interface guidelines. The key interface specifications are for the control hierarchy, labeling and nomenclature and how initial setup is performed. Lucasfilm calls for a three-level control hierarchy: a primary level (power, transport controls, etc.), secondary level (audio track selection, presentation and subtitle language selection, etc.), and a tertiary level that handles initial setup (aspect-ratio selection, etc.). Primary controls should be readily accessible from the front panel or from the main section of the re mote; secondary controls should be on the re mote or accessible via separate user menus. Tertiary controls are invoked via separate menu selections. Control nomenclature and labeling is judged by THX evaluators through hands-on use of the player, with and without referring to the owners’ manual.

Lucasfilm says that the audio portion of the Home THX standard for DVD players “rigorously examines fundamental audio performance in regard to distortion, noise, frequency response, and digital to analog converter performance—as well as some other areas of unique importance in the home theater environment.” In addition to frequency response, distortion, and noise, the specification ad dresses many of the performance characteristics routinely tested for Audio’s DVD player reviews, including output level and impedance, hum, spurious components, phase response (which I mention only if there’s some thing amiss), and converter monotonicity (again, mentioned only if there is some misbehavior). The THX requirements also address certain other characteristics that are not readily quantified with previously available test discs, lip sync being a prime example.

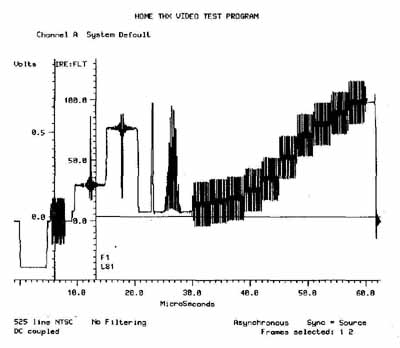

Arguably of more interest—if only because they are so new—are Lucasfilm video performance requirements and the test DVD devised to measure them. Although the THX Test DVD carries Lucasfilm-designed multipurpose test patterns that facilitate quasi-automatic verification of the major THX certification parameters by computer-controlled measuring equipment, it also carries dozens of other video test patterns that are useful with conventional waveform monitors and vectorscopes to accomplish much the same thing. Many of the patterns are replicated using a 16:9 aspect ratio as well as 4:3, the primary test set.

But the THX Test DVD also carries audio signals, among them being individual response sweeps for each channel, all-channel response sweeps at four levels, and a number of level sweeps from +20 to —100 dBr at various signal frequencies and with triangular and rectangular dither. (Since THX’s 0 dBr corresponds to —20 dBFS, the sweeps actually ex tend from 0 to —120 dBFS.) There’s also a twin-tone TM test and a track to check lip sync that should be useful. (I haven’t had the chance to use the audio portions of the disc on a real DVD player yet, so it’s difficult to comment on how these tests correlate with those made using the Dolby Laboratories test DVD.)

In addition to the audio and video test signals and patterns, the THX disc carries a number of motion picture recordings used for visual performance evaluation. Of these, one set is recorded with three 5.1-channel audio data streams of 384 kilobits/second (kbps) each, plus one two-channel audio track encoded at 192 kbps and subtitles. Another set is recorded with a single 5.1-channel audio track and very high video bit rates. In each group, the video bit rate is constrained to various levels to demonstrate the picture quality that is avail able under those conditions and the player’s ability to decode both low-rate and high-rate MPEG-2 encoded data.

The THX disc also contains a half dozen video “trailers” that are recorded in letterbox format with specified audio content. I’d say that these were the least useful chapters on the disc (which they are) except for the fact that some so-called test DVDs have more such stuff on them than useful test signals, whereas the THX disc is loaded with technically useful goodies. Among the video technical parameters cited in the THX certification specification are video level (often called luminance level or white level), luminance linearity (termed gray-scale linearity in our reviews), sync level (the strength of the horizontal sync pulse), chroma-burst level, chroma level (measured at 75% or 100% saturation), chroma differential gain and phase, and many other performance characteristics that I hope are now becoming familiar to you.

The ideal value for many of these parameters is defined by the applicable international standard, but international standards often do not address what constitutes an acceptable tolerance. ( U.S. standard-setting organizations, in particular, have traditionally opposed standardizing performance tolerances, on the basis that doing so serves to limit performance rather than to encourage better performance in the future.) The whole concept behind the THX certification program is to establish the performance bar where none exists and to raise the bar (as necessary) where one does exist, to ensure that a THX-certified player has no visual or sonic defects in its output. Thus, the unexpurgated THX certification document establishes permissible tolerances for all parameters Lucasfilm considers significant.

Let’s see how this works in practice. In a standard NTSC-composite signal, the “video” (luminance or white) level is de fined to be 100 IRE and the sync level is —40 IRE. That makes the overall level 140 IRE. Such a signal should produce an output of 1 volt peak-to-peak at the composite-video jack of the DVD player, because that is what a TV set expects to get. Thus, if things go according to Hoyle, a 140-IRE NTSC-composite video signal produces an output of 1 volt peak-to-peak, which makes 1 IRE equal to 0.007 1428 volts P-P. We’re really dealing with a voltage at this point, but waveform monitors (the oscilloscope-like devices used to measure video signals) are calibrated in IRE rather than in volts. That is why it is customary to refer to the proper video (luminance or white) level in terms of IRE (100 IRE) rather than in terms of voltage (714 millivolts peak to peak).

Since luminance and chrominance are recorded as separate information streams on DVDs, a DVD player’s NTSC-composite output must be created within the player. This makes the NTSC-composite chroma burst of particular significance because the burst, although not recorded on the disc, must be precisely correlated with the chrominance information that is recorded on the disc. If the burst level or phasing is incorrect, a properly adjusted NTSC-composite monitor will display incorrect chroma, the error being either in saturation or hue (tint), depending on whether the burst is incorrect in level or phase.

It also is important that the chrominance and luminance signals be precisely synchronized with each other. A color image can be thought of as comprising two parts, a mono chrome “brightness” or “luminance” that carries the actual picture detail and etches the outline, so to speak, and a chrominance signal that sort of paints on the colors, usually with lesser resolution. If the two signals are not perfectly synchronized, the color will be applied to the left or to the right of where it should be on the detail-laden monochrome component of the image and will tend to smear or soften the picture. What could have been a high-resolution picture (based on the video response of the luminance channel) now appears soft to the eye because of the improper luminance/chrominance timing. The THX disc has signals specifically de signed to evaluate this important characteristic.

Black level and gray-scale linearity (what Lucasfilm calls luminance linearity) can also be of particular significance in a DVD player. In the North American NTSC television standard, the black level (sometimes called black setup) is defined to be 7.5 IRE. In other words, full black is defined as 7.5 IRE, full white is defined as 100 IRE, and all shades of gray lie in between. In the PAL standard and in the Japanese NTSC standard, full black is defined as 0 IRE. The player scales the luminance signal (after MPEG decoding) to suit the standard that applies to the region in which it is used. It’s wise to check that it does so properly, which ex plains the need to measure black level as well as gray-scale linearity.

Chroma differential gain and differential phase are related to gray-scale linearity in that they measure changes in chroma level or phasing caused by changes in scene brightness (luminance, or white, level). Such errors cause changes in color saturation and tint, respectively, that are correlated with scene brightness. In my experience, this is rarely a problem with DVD players, but it’s a good idea to make sure. The THX disc has the signals necessary to perform these measurements, and Lucasfilm has established limits that are below the threshold of visibility.

Of course, the luminance and chrominance resolutions are very important, and the THX disc carries several different signals that can be used to evaluate them. There are multiburst sets to check luminance-channel response at specific frequencies, luminance and chrominance frequency sweeps that enable more continuous (albeit usually less precise) response measurements of both channels, multipulses to evaluate both response and chrominance / luminance time synchronization as a function of frequency, and various bars and windows that are helpful in establishing low-frequency video response (“waveform tilt”). Most of these test patterns can be used with either automated or non-automated test equipment; one that requires spectral analysis of the video signal (and so cannot be used with conventional wave form monitors and vectorscopes) is the six pulse. It contains equal energy at all harmonics of the horizontal scan frequency (usually up to a specified frequency) and is used to spot-check luminance-channel frequency response and (if the test is performed with a Fourier analyzer) phase response. The THX disc also contains full-field color signals that can be used to measure AM and PM (amplitude- and phase-modulation) chroma noise. Luminance channel noise is usually measured with a 50-IRE gray field. There are shallow mid-level luminance ramps to check video D/A converter monotonicity and shallow ramps at all levels (with chroma) to widen the test range. There are windows at a variety of luminance levels (20 through 100 IRE) that I find useful in checking overshoot. And there are a number of other tests that go beyond the scope of what I can discuss here. In all, there are some 52 different test signals for evaluating video performance in the 4:3 aspect ratio alone, and many of these serve multiple purposes.

All in all, the THX Test Disc is a magnificent piece of work and signifies a big step forward for DVD. Kudos, hats off, and thank you, Lucasfilm!

Adapted from 1998 Audio magazine article. Classic Audio and Audio Engineering magazine issues are available for free download at the Internet Archive (archive.org, aka The Wayback Machine)