By ANTHONY H. CORDESMAN

Company Address: dCS, c/o Canorus, Inc., 240 Great Circle Rd., Suite 326, Nashville, Tenn. 37228; phone, 615/252-8778; fax, 615/252-8755; canorus.com.

CD is dead, long live CD! While this may sound like a paradox, it isn't with this equipment. The Data Conversion Systems (dCS) Elgar digital-to-analog converter offers you the opportunity to go on to the next generation of digital sound while still enjoying the current generation to its fullest potential.

The Elgar is the most flexible D/A converter I know of, capable of playing not only CDs and DATs but also 88.2-kHz recordings and the new 96 kHz/24-bit "DADs" introduced by Chesky and Classic Records (see page 32). It is also ready for 192-kHz recordings, should they eventually become available, and can be upgraded to handle the Direct Stream Digital (DSD) coding that will be used for the Sony/Philips Super Audio CD format.

For this review, dCS also sent me its 972 digital-to-digital converter, which enables you to extract further detail out of existing CDs by increasing the sampling rate fed into the D/A converter from 44.1 kHz to either 96 or 192 kHz. It cannot recover information that isn't there, but it does produce a cleaner and more transparent sound, ensuring that your existing disc collection will provide as much musical enjoyment as possible.

At $12,000, the Elgar does not come cheap. (The 972, which is designed primarily for the pro market, is priced at $5,750.) But it offers as good a guarantee as any D/A converter around against obsolescence and the problems created by today's format wars. It also has excellent volume and balance controls that enable it to drive a power amplifier directly, without a preamp. These features make the Elgar a consider ably safer investment than most of today's best D/A converters.

Data Conversion Systems is a top supplier of digital equipment to recording studios and mastering houses and until recently has not had much of a presence outside of that market. The Elgar is actually a consumer version of the company's professional D/A converter. Unlike some consumer products derived from professional gear, however, the Elgar is very user-friendly. It is nicely styled and relatively svelte (16.1 x 2 3/4 x 14.1 inches), weighs a little under 7 pounds, and does not require a separate power supply. As a result, it can fit easily into almost any rack or shelf space.

The Elgar has a large array of in puts and can be used with any digital interface except the PS bus connection. There are two AES/EBU inputs and four S/PDIF inputs (one BNC, one RCA, one ST optical, and one Toslink optical). Both balanced and unbalanced stereo analog outputs are provided. The front-panel LCD display is excellent, conveying an un usually wide range of information (including the precise sampling frequency of the signal at the selected input).

The Elgar's front-panel controls are "Standby," "Display," "Phase," "De-Emphasis," "Input," "Mute," and "Volume/Balance." Changes to the volume or balance setting are displayed precisely in the front-panel LCD, making them easy to repeat.

I found the Elgar's size and ease of use to be a refreshing contrast to some of the clunkier high-end products. In contrast, the remote control is large, metal, and clunky but nonetheless perfectly adequate for the job.

This is one component that saves its best for where it really counts-the inside, which is truly impressive. One of the pleasures of really good high-end gear is the elegance of internal construction and circuit layout. Although I can't recommend using a glass top to show off the Elgar's interior, it is beautifully built, and its digital-to-analog circuit board is one of the most complex I have ever seen.

DCS was among the first companies to develop professional 96-kHz/24-bit equipment (the 902D A/D and 952 D/A converters), and the Elgar shares much of that technology. In particular, it uses what dCS calls a "ring DAC," which is said to avoid the pitfalls of both 1-bit (bitstream) and conventional multibit converters. DCS con tends that a 1-bit converter has good linearity but that, because it must run at very high speed internally, it is prone to noise and distortion caused by small clock errors. And dCS says that it's difficult to apply noise-shaping aggressive enough to overcome a two-level quantizer's inherently poor S/N and achieve an extremely low noise floor.

Multibit converters, on the other hand, rely on current sources set by a resistor chain. This chain requires resistors that ad here to unusual values with extreme precision, which are difficult to manufacture and then subject to drift over time and with changes in temperature. As a result, dCS feels multibit converters are prone to poor low-level linearity and cannot accurately resolve low-level signals.

DCS claims that the ring DAC in the Elgar operates at a relatively low oversampling frequency compared to 1-bit converters and that the consequently lower clock speed reduces its susceptibility to jitter. The ring DAC is not a traditional multibit converter, either. It is built around a 5-bit modulator, which is said to eliminate the problems associated with using resistor chains to define extremely small current values while yielding good stability over time and changes in temperature.

The Elgar is designed to facilitate future upgrading. It has custom-designed, soft ware-based digital filters, and programmable gate arrays, which read from its EPROM, are used for a wide range of signal processing and routing tasks. In the current design, only 20% of the EPROM's capacity is occupied, leaving plenty of room for new software.

------------

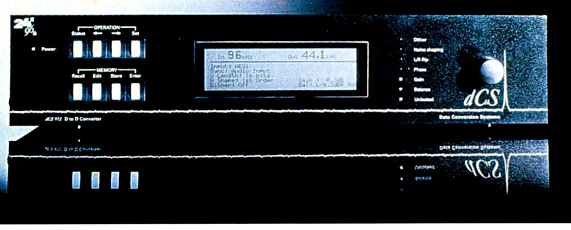

The dCS 972 sampling-rate converter

The Elgar already is capable of 24-bit, 96-kHz conversion, and its sampling-frequency limit is being raised to 192 kHz. This compares to the 18- to 20-bit, 48-kHz ceilings of most competing D/A converters (al though a few competitors use partial 24-bit processing, and several manufacturers have said they will soon introduce full 96-kHz/24-bit converters). Equally important, the Elgar can be upgraded to handle the DSD process (but only for two channels) that Sony and Phillips plan to introduce next spring in the Super Audio CD format.

This makes it a universal converter with respect to both existing signal sources and the new stereo formats that are currently under discussion.

DCS has issued several white papers sup porting the desirability of moving to higher data rates for digital audio. One particularly interesting argument the company makes is that the reason for going to 24-bit A/D and D/A conversion is not to achieve 140+ dB of dynamic range but, rather, to improve overall performance. DCS says that the high-precision clocks required for 24-bit conversion, the recording headroom and effective dynamic range, the low differential nonlinearity, and the avoidance of gain-ranging are all critical factors affecting sound quality.

The company also argues that sampling frequencies of 96 kHz and higher are the lowest that yield neutral reproduction without audible ringing from anti-aliasing and reconstruction filters. It says that the filters used for 44.1- and 48-kHz sampling spread their audible impact over a relatively long time period and that even a 96-kHz filter presents some problems, though it keeps the energy associated with transients to within ±100 microseconds (versus 400 to 500 microseconds for 44.1- and 48-kHz conversion). Raising the sampling rate to 192 kHz is said to reduce the smear to ±50 microseconds. DCS argues that these energy-decay characteristics are clearly audible at-40 dB for 44.1- and 48-kHz conversion and that this helps to explain why higher sampling rates produce cleaner realistic soundstage.

Anyone who has followed the literature, including Bob Stuart's recent articles in Audio, knows that there are different views regarding what word length and sampling rate are really necessary. However, both Chesky and Classic Records-companies that are now introducing 24 bit/96-kHz discs have experimented with a range of word lengths and sampling frequencies and say that each increase has produced a clear improvement in sound quality.

I have not had the opportunity to do this kind of comparison for myself, but my listening sessions with the Elgar did make a powerful case for the excellence of its performance in reproducing both CDs and the new 96-kHz/24-bit releases. I compared the sound of the Elgar principally to that of a Theta Digital DS Pro Generation V-- a Balanced D/A converter, which also is capable of handling the 96-kHz sampling rate, has 24-bit resolution going into the DAC, and can produce the equivalent of a 20-bit out put. I also compared it to a Mark Levinson No. 30.5 and several other high-quality D/A converters and CD players.

It is difficult to generalize about the differences in the way very-high-quality D/A converters reproduce CDs without extensive listening to a wide variety of CDs and trans ports. In some cases, I find that the sound quality of the disc itself makes it impossible to explore the limits of the D/A converter's capabilities. In others, high-quality converters sometimes produce clearly audible improvements in old or low-quality CDs, al though in ways that differ in sonic nuance and detail, depending on the particular CD and DAC.

The best converters provide more consistent improvements in sound quality with the latest high-quality DDD CDs, particularly those made from 20- to 24-bit master tapes by way of noise-shaped down conversion, such as Sony's Super Bit Mapping (SBM) process. These improvements are particularly apparent when you're playing well-produced CDs of acoustic instruments recorded with minimal miking and mixing. The differences inevitably vary in detail, but it is hard to say that the qualities of one top converter are decisively better than those of another without access to the original master tape.

What you hear also depends on the transport and interface used with a D/A converter. (I used the Theta Jade and David transports, although I also tried the Elgar with Mark Levinson and Wadia Digital front ends in friends' systems.) It is clear that the choice of transport, interconnect, and interface does have an impact and that the different levels of synergy between different mixes of transport, interconnect, and D/A converter mean that you have to listen to a given combination to know exactly what sonic characteristics you will get.

After all of my listening, I can state that I have never heard a D/A converter that sounded better than the Elgar. It has superb low-level resolution, transparency, and de tail. Its soundstage is as clean as any that I have ever heard. It provides excellent depth whenever there is depth in the recording, and its localization of voices and instruments is equally excellent, without any broadening of the image or artificial spot lighting. Upper-midrange and treble performance are as good as the CD permits, and midrange reproduction is state of the art. You may hear slightly different nuances with other D/A converters, but you will not hear superior sound. (I found the Elgar was better still when I bypassed my preamp and avoided the need for an extra set of inter connects. The sound got even cleaner and more transparent.) If there are any areas where other D/A converters have a slight advantage, they lie in the bass and in dynamic contrasts. The Elgar's bass was excellent in terms of extension and detail, but it did not always have the power and drive of the Theta's.

Some will argue that the Theta slightly exaggerates the deep bass (the Levinson converter sounded closer to the dCS), others that the Elgar is just slightly soft. (This is yet another reason you have to listen to various combinations yourself.) The same kind of differences emerged in terms of dynamics. Both the Elgar and Theta deliver excellent dynamic contrasts, with a great deal of natural energy and life.

They are often strikingly superior in bringing back the life that's missing from CDs heard through many less advanced converters. The Theta, however, often produced sharp dynamic contrasts from CDs containing a great deal of high-energy music, such as orchestral music, opera, and jazz bands. The Elgar often produced more musically natural contrasts with chamber music and smaller jazz groups. Once again, the Levinson sounded closer to the dCS, but this time, so did the Wadia.

But now, let's introduce the dCS 972 into the equation. This professional sampling-rate and format converter was designed for studio use, and it very definitely is only for the ultimate audiophile. Most people are never going to need to convert from one sampling frequency to another, and the only reason for adding the 972 to a home system is that increasing the sampling frequency from 44.1 to 96 kHz (or the 192 kHz that will soon be incorporated) makes most CDs sound better.

Why? Well, dCS really doesn't have a scientific explanation. In fact, the company sent me the 972 to play around with only because they had found by listening that it improved sound quality. And they are right, although the effect is not dramatic. What you get are cleaner and better transients, more low-level information, slightly cleaner and faster bass, sweeter upper midrange, more low-level soundstage information, and greater depth. (The 972 also worked well, incidentally, with the Theta DS Pro D/A converter and would probably work just as well with any other DAC capable of handling high sampling rates.

The level of improvement did, however, depend on the quality of the recording.

The improvement with old CDs was least predictable. Sometimes the dCS 972 could clean up an old CD in ways that were immediately apparent. Other times, there was little, if any, difference. The improvement with newer CDs was more consistent but less striking. I could almost al ways hear an improvement in detail and transparency, but it was usually slight. It was usually more apparent when I re moved the 972 from the system than when I inserted it. This subjective phenomenon seems to occur with many subtle sonic enhancements: You do not notice improvement as quickly or easily as you notice degradation.

The 972's effect also depended to some extent on the front end and interface: The better the CD transport, the better the sound. Really good AES/EBU cables and connections sounded better than any type of S/PDIF connection. Placing a Genesis Digital Lens between the transport and the 972 helped in some cases but not all.

In short, you have to experiment with the dCS 972 to find the best synergy between it and the rest of your digital gear, and its importance will vary by system and listener. The only way you can evaluate the relative value of the 972 is to listen to it with your components and a variety of CDs. I can assure you that you will hear some benefit, but whether you find this benefit worth $5,750 in your system is something only you can judge.

The most exciting part of my sessions with the Elgar came when I started listening to the new 96-kHz/24-bit DVDs from Chesky and Classic Records. Please under stand that these are early days. I did not have a dedicated transport, although 1 did have access to Theta Digital's new David DVD player, which is said to have the exceptionally low jitter needed to reproduce 96-kHz/24-bit. The David also passed a full 96-kHz/24-bit data stream to the Elgar. (All DVD players must be able to handle 96 kHz/24-bit PCM audio internally, but most of them down-sample it-to 48 kHz/20-bit, for example-before passing it to their own D/A converters or to their digital outputs.) The Elgar's performance with the 96-kHz/ 24-bit discs was stunning; I can hardly wait until more become available and the industry moves permanently beyond CD. The differences in sound quality between CDs and 96-kHz/24-bit releases are far more important than those you hear in going from a mid-grade to a top-of-the-line CD transport or D/A converter.

With a D/A converter like the Elgar, 96 kHz/24-bit digital audio is a real rival to analog. Classic Records gave me the same material on 33 1/3- and 45-rpm phono discs, CD, and 96-kHz/24-bit DVD. A lot of this material came from old analog masters. I found the 96-kHz/24-bit versions to be far better than the CD renderings and as good as the 45-rpm record. Much as I love my turn table, the lower noise of the 96-kHz/24-bit digital was generally more important to me than the superior midrange detail I still sometimes heard on records. I came away feeling that, relative to LPs, 96-kHz/24-bit recordings offer a more enjoyable and accurate way of reproducing performances re corded on analog tape and that they combine most of the best features of analog and CD.

Chesky provided a disc made directly from 96-kHz/24-bit digital master tapes, and it gave me an indication of what can be done with the latest equipment, simple miking, minimal processing, and high-quality digital transfers. Voice was notably cleaner than on the comparable CD. There was an immediate increase in low-level de tail and presence. Strings and guitar were more realistic. Drum percussion transients were cleaner and more precise. Imaging improved, recordings became more live and dynamic, and upper-midrange over tones became sweeter and more harmonic.

I won't say that the 96-kHz/24-bit recording sounded "live"-only real life ever does-but it sure sounded much more like a master tape than CD.

Although CD can hardly be considered dead, I have heard the future, and it is clear that it is possible to establish a whole new plateau of sound quality. If the audio industry shows any intelligence at all in re solving the looming format war between DVD-Audio and the Sony/ Phillips Super Audio CD, every aspect of high-end sound will be redefined. As I suggested in the be ginning, CD is alive, but long live the new alternatives!

-----------------------