In many ways, broadcasting is like most other businesses in the United States.

Broadcast owners range from conglomerates with several broadcast properties to small town businesspeople who own a single AM station. Regardless of the type of broadcast property they have, all broadcast owners are in the business to make a profit.

Broadcasting differs from other businesses in that broadcasters do not make their money from selling a product directly to the listener or the viewer.

Instead, they get their money from the advertiser, who pays them to carry the advertising message to the broadcast audience-all potential consumers of the advertiser's product. If the broadcaster presents programming that attracts a large audience, the broadcaster becomes more attractive to the advertisers and hence is able to make a greater amount of money. Thus, success in the business of broadcasting is determined primarily by popular programs, large audiences, and advertising dollars.

Broadcasting also differs from other businesses in the degree of government regulation it is subject to. The government limits the number of stations that can be owned by an individual or company, sets forth regulations for the operation of these stations, and has the power to grant and renew station licenses.

As can be seen in Figure 4-1, the networks, individual stations, advertisers, program producers, syndicators, and the government are all part of the structure of the broadcast industry. Although it is an industry noted for its glamour and social influence, broadcasting is first a business and, as such, cannot be understood without understanding its economic structure. In the discussion that follows, we will concentrate on this business structure and how it influences decision making in the broadcast industry.

BROADCAST OWNERSHIP

One of the basic principles behind broadcast regulation is that, in order to protect freedom of speech and the public's right to a range of freely expressed ideas, no single individual or corporation should be allowed to gain too much control over the broadcast system. In order to insure that this did not happen, the government, through rules and regulations, put limits on broadcast ownership. The rules and regulations prescribe that an individual or corporation can own no more than seven AM, seven FM, and seven television stations (often called the seven-seven-seven rule). In the case of television, the rules specify that no more than five VHF stations can be owned by the same party.

The rules and regulations also limit owners to one station of each type (AM, FM, VHF, or UHF) in a single geographical area. For example, you cannot own two AM stations in a single city, but you can own one AM, one FM, and one TV station.

The regulations limiting station ownership were intended to give many different persons and organizations access to the broadcast spectrum. These rules, however, did not take into account that station location might be even more important than the number of stations that any one person owned. As broadcasting grew, it was apparent that a station in a large population area was more powerful and valuable than a station in a small population area. Therefore, owners who had stations in cities such as New York and Los Angeles could exercise greater influence and attract a much larger share of advertising dollars than stations in areas such as Grand Rapids or Omaha.

In order to understand the American broadcasting system it is necessary to look at two aspects of ownership: market areas and ownership patterns.

----------------

Advertisers (Buy commercial time from stations and networks to advertise products)

4 Audience

FEDERAL COMMUNICATIONS COMMISSION (FCC)

(Issues broadcasting licenses and regulates operation of the broadcasting industry)

Networks (National organizations that provide programming and advertising to stations)

O & O's (Stations that are owned and operated by the network)

Programs Audience Stations Market Size (Various population areas reached by broadcast signals)

Licenses

Good behavior

Affiliates Independents (Stations that Stations that contract with obtain their own networks to programming and receive programs, ads, advertising, and revenues from advertising)

4 Programs Producers (Make programs that are sold to networks or stations)

Syndicators (Provide or produce programs that are sold directly to stations)

Figure 4-1. The economic structure of television. Sources: Access 20

( October 6,1975), pp. 10-12; Bruce Owen, Jack H. Beebe, Willard G. Manning,

Jr., Television Economics, Lexington Books, 1974, p. 7.

---------------------

MARKET AREAS

As the broadcast industry began to grow, the system of market areas evolved.

The term market area refers to the geographical area that is reached by a radio or television signal, and to the population living within that area. For example, New York is the number one market area because it has the greatest number of people in a geographical area reached by a broadcast signal. New York has over six million households with at least one television set; Los Angeles (the number two market) follows, with three and a half million; and Chicago (number three) is next, with almost three million.

A broadcast property in a major market (the top fifty markets are considered major) is more valuable than property in minor markets because the larger the population, the greater the audience for advertising messages and, hence, for potential sales. When broadcast stations were still widely available, those who were aware of the importance of market areas were quick to obtain licenses in major markets. For example, all three national networks-ABC, CBS, and NBC-acquired licenses for stations in New York, Los Angeles, and Chicago, as well as in several other major market areas. Today these network owned and-operated stations are among the most powerful and profitable in the United States. Not only do they reach a substantial portion of the nation's population, but they also provide almost one-third of the networks' profits. 1

TABLE 4-1 The Ten Largest Television Multiple Ownership Groups Ranked

by Average Daily Audience, 1972 ---- Source: Walter S. Baer et al.

BROADCAST OWNERSHIP PATTERNS

Multiple and Single Ownership

The network owned-and-operated stations, known as 0 & Os, are an example of multiple ownership. Multiple ownership exists when an individual or a company owns two or more stations in different communities. The networks are typical examples of multiple owners. Over 50 percent of all of the television stations in the United States are owned by multiple owners. More importantly, such stations reach 74 percent of the total potential audience in the United States. The most important multiple owners own stations in the largest markets. Some of the giants of American broadcasting are listed in Table 4-1.

Although there are still those who own a single station or several kinds of stations in only one market area, the trend has been toward multiple ownership. In the 1950s television stations were more likely to be owned by single owners than by multiple owners. By the 1970s, however, the situation had reversed; a substantial majority of television stations were owned by multiple owners. The trend toward multiple ownership affects both radio and television stations. For example, with the exception of two stations, WBLS-FM and WMCA-AM, all other commercial radio stations in New York City are either owned by multiple owners or owners with other media interests.

The potential influence of large multiple owners is illustrated by the following statistics: the stations owned by the fifty largest multiple owners reach about two-thirds of all television homes in the nation; the twenty-five largest multiple owners reach one-half of all television homes; and the ten largest multiple owners reach one-third of all television homes.

Cross-Media Ownership

Cross-media ownership occurs when an individual or group owns media property in two or more different media in the same market area. The most common type of cross-media ownership is owning broadcast property along with newspapers, magazines, or both. When radio first began to develop, newspaper publishers were among the first to establish radio stations; later they moved into both FM and television. Presently, many newspapers own AM FM-TV combinations. In major markets, for example, the New York Times Company owns WQXR-AM and FM in New York. The Washington Post owns WTOP AM-TV; the St. Louis Post-Dispatch, KDS television and radio; the St. Louis Globe-Democrat, KTVI television; and the Milwaukee Journal, WTMJ AM-FM-TV. In several minor markets, single owners own all of the newspaper and broadcasting facilities. This system of single ownership in minor markets means that most media information comes from one source.

Although the FCC has often expressed concern that newspaper and broadcast combinations could reduce the public's access to differing opinions and decrease competition for local advertising, it has not prohibited cross media ownership. In 1977, however, the United States Court of Appeals ruled that the same company could not own a newspaper and a television or radio station in the same city unless the company could clearly demonstrate that cross ownership was in the public interest. Although the effect of this ruling is not yet clear, it is likely that for the next several years newspapers will argue that their ownership of broadcast property is in the public interest and will therefore be able to avoid or delay selling their broadcast property.

Conglomerate Ownership

Many of the country's corporations also own broadcast stations. Some of the giant corporations such as CBS, have broadcasting as their primary interest, but other stations are subsidiaries of corporations which are not primarily engaged in broadcasting or other media. An example of such an organization is Wometco Enterprises Inc. Wometco, chiefly known as a soft drink bottler and vending machine operator, also owns the Miami Seaquarium, ninety-seven movie theaters, cable television systems in seven states, and three wax museums. Wometco's station holdings are relatively small, one FM and three TV stations. Nevertheless these broadcast properties account for 55 percent of Wometco's profits. 4 Other examples of corporate owners of broadcast properties include: General Tire and Rubber Company, Dun and Bradstreet, General Electric, Schering-Plough Company, Kansas City Southern Industries, Kaiser Industries, Pacific Southwest Airlines, Rust Craft Greeting Cards, and many others.

-------------

HEARST CORPORATION

The Hearst Corporation is an example of a multi-media giant.

Hearst owns one newspaper in Maryland, two in New York, two in Massachusetts, one in the state of Washington, two in California, and one in Texas. Some of these papers are in major cities such as Albany, Baltimore, Boston, Los Angeles, San Francisco, and Seattle. Hearst also owns a comic weekly that is a newspaper supplement.

In addition, Hearst owns the following magazines: Cosmopolitan, Good Housekeeping, Harper's Bazaar, Town and Country, House Beautiful, Motor Boating and Sailing, Sports Afield, Popular Mechanics, Science Digest, and American Druggist. Hearst also owns Avon Books.

Hearst properties in broadcast stations include an AM, FM, and TV station in each of the following cities: Pittsburgh (market number 10), Baltimore (19), and Milwaukee (22). The corporation also owns an AM station in Puerto Rico.

Source: Broadcasting Yearbook 1976 Broadcasting Publications Inc., (Washington, D.C., 1976), p. A-47.

---------------------

One of the main sources of information about the business of broadcasting could come from the financial records of the corporations. When large corporations are involved in broadcast ownership, however, the actual ownership of the property and its financial status can often be obscured in a maze of complicated ownership structures. For example, Corinthian Broadcasting Corporation, the licensee for five television stations, is a wholly owned subsidiary of the wall street investment firm of Dun and Bradstreet. But eight different banks own 34.1 percent of the shares of Dun and Bradstreet, so it is difficult to determine who actually owns the stations.

Corporations that are privately owned are not required by law to disclose any financial information unless they buy or sell broadcast property. An example of a private corporation that owns a broadcast property is the Chicago Tribune, which owns WGN-TV. Publicly owned corporations are required to disclose their earnings, but financial information concerning their broadcast can easily be buried in the overall holdings financial report. Westinghouse, a major owner of broadcast stations, lists its broadcast earnings under the category of "Broadcasting, Learning, and Leisure Time." Since this category includes earnings from other Westinghouse activities such as soft drink bottling, watch manufacturing, and the Westinghouse Learning Corporation, it is impossible to obtain very much information about the financial workings of the Westinghouse stations.

---------------

COLUMBIA BROADCASTING SYSTEM

CBS is a conglomerate whose primary interest is still in broadcasting. The broadcasting part of CBS is also the most profitable-network 0 & 0 stations provide 46 percent of CBS revenues, 74 percent of net profits. Columbia Records, a division of CBS, is also very profitable.

In 1964 CBS began to diversify and buy companies that were not part of the broadcasting business. CBS now owns the following: Musical instruments: Fender Guitar, Rhodes, Electro Music, V. C. Squier, Rogers Drums, Steinway, Gulbransen.

Publishers: Holt, Rinehart & Winston, W. B. Saunders, Anthony Blond (British), Popular Library, Nueva Editoriale Inter-americana SA, Movie Book Club, Praeger Publications, Fawcett Publications.

Records: Discount Records.

Magazines: Field and Stream, Road and Track, Cycle World, PV4, World Tennis, Sea Magazine, Women's Day.

Educational films: Bailey Films, Film Associates.

Audio: Soundcraft, Pacific Stereo.

Music publisher: Tunafish Music.

Posters: April House.

Toys and hobbies: Creative Playthings, National Handcraft Inst., X-Acto, Needle Arts Society.

CATV: Two systems in the United States and several in Canada.

Source: Forbes, May 1, 1975, p. 23.

--------------

--------------

THE BROADCAST BUSINESS

Number of Stations

Total Radio 8,240

Commercial AM 4,497

Commercial FM 2,873

Noncommercial FM 870

Total Television 984 Commercial VHF 517 Commercial UHF 211 Noncommercial UHF 155 Noncommercial VHF 101 Set Saturation 71.5 million homes with TV sets (97 percent of all homes)

54 million color sets 425 million radio sets (estimated)

Source: Broadcasting Yearbook 1977 (Broadcasting Publications, Inc.: Washington D.C., 1977) p. A-2.

--------------------

THE FAILURE OF DIVERSIFICATION OF BROADCAST OWNERSHIP

Although the Communications Act of 1934 had the intent of creating a system in which many people would have access to broadcasting licenses and in which broadcasters would be part of the local community where the stations were located, it is now clear that the effort to ensure diversification has failed. Much of broadcasting is in the hands of large corporations, and most broadcasters live far away from the communities where their stations are located. Broadcast licenses-at least in desirable market areas-are all taken, and there is likely to be little change in the pattern of broadcast licensing.

Since diversification was a concept originally created in order to promote public exposure to a wide range of ideas, the failure of diversification forces us to consider whether the result has been a limiting of ideas and free speech.

Those who favor concentrated ownership argue that this type of ownership is more stable economically, that the owners are able to make greater programming efforts, and that they are more likely to attempt innovations in technology. Those who argue against concentrated ownership claim that it presents greater potential for abuse in advertising rates, for information control, and for conflicts with other business interests. They also argue that if concentrated interests were broken up, there would be more of an opportunity for minorities and other under-represented or unrepresented groups to own stations.

In 1974, a project group of the Rand Corporation gathered and assessed all of the past research that has been done on media concentration and broadcast performance. After analyzing all of this research, they concluded that there was no convincing evidence to either prove or disprove the theory that media concentration affects program content.? But David Halberstam, in his 1975 study of CBS, argued that as CBS grew into a giant corporation it became much less likely to engage in controversy and controversial commentary in its news and public affairs programming. 8 Thus, it is clear that issues concerning the impact of media concentration are by no means resolved.

The fact remains, however, that broadcasting is big business and the decisions that are made about programming, sales, and personnel are all fundamentally business decisions. In order to understand how this business works, we will look more closely at the structure of the networks and the stations.

THE EXTERNAL STRUCTURE OF NETWORKS AND STATIONS

Networks There are three full-time commercial radio and television networks in the United States: the American Broadcasting Company (ABC), the Columbia Broadcasting System (CBS), and the National Broadcasting Company (NBC). There is also one sizable national radio network-the Mutual Broadcasting System (MBS), as well as several regional or special interest radio and television networks.

Networks provide three basic services for their member stations, which are known as affiliates: 1) they purchase or produce programming for distribution to their affiliates; 2) they sell commercial time to national advertisers and give a certain percentage of the revenue from such sales to their affiliates; and 3) they arrange for technical interconnection so that affiliates can receive network programs.

The Columbia Broadcasting System changed its name to CBS Incorporated in 1974.

Contrary to popular belief, the stations are not in the business of producing programs-they are in the business of providing audiences. Although most stations produce a small amount of local programming, it would be too expensive for individual stations to produce their entire program schedules; therefore, the stations depend on networks for most of their programming.

By offering "desirable" programming to their affiliates who are located throughout the country, the network is able to attract a nationwide audience.

The network then offers this audience to national advertisers. The network that offers the most desirable programming attracts the largest audience and, consequently, the largest share of the advertising dollar.

The money that the network gets from advertising accounts for the greater share of its revenues and profits. The advertising revenues from a program (and its reruns) pay the cost of purchasing or producing a program and distributing it to the affiliates. Networks also make a substantial profit from their owned--and operated stations.

Networks are highly profitable business organizations. In 1976, CBS net work had a pretax profit of $129 million while NBC and ABC each had a pretax profit of $83 million. These figures represent an increase, from 1975, of 22 percent for CBS and 13 percent for ABC. Due to ABC's new programming strategy, which made it the top rated network, ABC had a startling 186 percent increase in profits from 1975!

Owned--and Operated Stations

Each of the three networks owns and operates five commercial VHF television stations. These stations, called 08rO's, are the aristocrats of television stations.

Not only are they all located in major markets, but they also provide almost one-third of each network's yearly profit and they are training grounds for entertainment talent, news personnel, and management before they reach the big time of the networks. As well as being owned and operated by a network, each 06r0 is also an affiliate of the network that owns it.

The three networks combined also own 17 AM and 17 FM stations. Many of these stations are located in cities where the network owns TV stations (See Table 4-2). Network Affiliates Although many radio stations affiliate with networks, this . affiliation is not very crucial to the operation of a radio station: a radio station will usually depend on a network only for news and public affairs programming. In addition, the greatest percentage of commercial time in radio is sold locally, and so, although the radio station might earn revenue from national advertisers, such earnings are only a small percentage of its total revenues.

Eighty-five percent of all television stations affiliate with networks. NBC has 213 affiliates; CBS has 197: and ABC has 183, with an additional 67 secondary affiliates. Secondary affiliation means that the stations might also have an affiliation with another network.

For television, network affiliation is the most practical and profitable way of running a station. The affiliate takes programming from the network for two basic reasons: the money the affiliate makes from the network is more than the affiliate could make if it developed its own programming; and the network offers certain programming that stations must provide in order to meet FCC requirements.

A portion of the money that the networks get from national advertisers goes directly to the network affiliates as payment to them for airing the commercials.

The network-affiliate contract calls for a complex exchange of funds. Basically, the network pays the station for each commercial the station carries from the network. The amount of payment is determined by the size of the station's audience-the larger the audience, the greater the payment. The networks also offer another source of revenue to their affiliates by leaving a certain amount of time open around the network prime time programming that the affiliate is free to sell to local, regional, or national advertisers. In return for providing programming and commercials, the network charges the affiliate for the inter connection between the affiliate station and the network, but the affiliate gets more money from the network for carrying commercials than it pays to the net work for the interconnection.

TABLE 4-2 Network Owned-and-Operated Radio and Television Stations

*Figures compiled by the American Research Bureau

Source: Broadcast Yearbook 1977 (Washington, D.C.: Broadcasting Publications, Inc., 1977) pp. A34, A:35, A41, B80, B81.

When the affiliate station is not receiving network programming, it is free to sell commercials for all the programs it purchases or produces. Stations most commonly sell commercial time for locally produced programs, feature films, and programs they buy from syndication companies.

The FCC regulates contracts between networks and their affiliates. The Commission has ruled that no network can have an exclusive agreement with a station that would prevent the station from using another network's programming. In fact, in some cities with only one or two television stations, stations use programs from two different networks. Other regulations state that net work-affiliate contracts are limited to two years, that stations may refuse any unsuitable programming, and the network cannot require the station to clear time whenever the network wants. Networks are also prohibited from influencing advertising rates for non-network programs.

Although these rules are designed to protect the stations, and sometimes the network, they do not prevent the station from complying voluntarily with network wishes. Generally the most profitable stations are those that are affiliated with networks, and a station that earns the network's favor is able to negotiate for better rates on its next contract. Therefore, stations usually strive to comply with network requests.

Independent Stations

Some television stations-the independents-are neither affiliated with or owned by a network. They account for 10 to 15 percent of the total commercial television stations and are usually found only in large and medium markets.

Generally, independent stations do not enjoy as much financial success as net work affiliates because they do not have as much money available for talent and programming. Not only do they have to produce or purchase all their programming, they also must sell all their own advertising time. In 1972, 67 percent of the VHF independents showed a profit, while only 21 percent of the UHF in dependents were profitable. In comparison, among the network affiliates 86 percent of the VHF stations and 44 percent of the UHF stations were profit able." There are also independent radio stations. However, the question of independent status versus affiliation is not nearly so important in radio as in television, since radio stations are not so dependent on networks for programming and advertising revenue.

A Fourth Network?

When Norman Lear created "Mary Hartman, Mary Hartman," he offered the program to the networks. After the networks refused it, he sold the program to many independent stations throughout the country. The program was so successful in generating advertising revenues that the independents began to think about creating a limited network of their own. By 1977, the independents, acting collectively, began to commission some of their own programs. Rather than following the established network practice of selling most of the commercial time on a national basis with revenues returning to the networks, the independents decided to sell the majority of commercial spots in their own market areas. This strategy has been so successful in creating substantial profits for the independents that, although an independent network is still in an experimental stage, the independents are confident that they will soon be able to compete with the networks for advertising dollars and audiences during the prime time period.

THE INTERNAL STRUCTURE OF NETWORKS AND STATIONS

As with all businesses, networks and stations are divided into various operating departments that have specific jobs to do. The divisions are basically the same for both the stations and the networks, although in the case of smaller stations some of the jobs may overlap. Generally, there are seven divisions; management, programming, production, sales, traffic, engineering, and broadcast standards.

Management

Management is responsible for the overall operation of the networks and stations. Management personnel set the direction, philosophy, and programming format of each station or network, and all of the various divisions operate within management guidelines. In a network operation there may be as many as fifty people in top management positions, whereas a smaller station's operations may be managed mostly by the station owner.

Programming

At the network level there are hundreds of people who operate in the programming departments. They range from those who make decisions about what pro grams to purchase or produce to those who actually produce, write, and appear in programs. Those who work in news departments are separate from the rest of the programming staff. News department personnel range from executive producers to correspondents and writers. The most successful programming executives are those who purchase and produce programming that appeals to the widest possible audience.

At the local level, if the station is a network affiliate, the majority of programming will come from the network. Local station programmers must fill up the remainder of the broadcast schedule with local programming, feature films, and programs from syndication companies. In a radio operation, where music is the most common format, those involved in programming must choose the records that will best fit the station's format.

Production In the networks, production personnel are separate from the programmers.

Network production staffs include directors and camera and sound equipment operators. At the local level, programming and production functions often overlap--one person may both write and direct a program or, in radio, one person may write, announce, and run the audio control board.

Sales

Since the primary economic support of broadcasting is advertising, the sales department is the heart of any broadcast organization. The sales department sells advertising time. If the organization is a network, commercials are most often sold on a national level. For an individual station, the sales staff will concentrate on local or regional sales. Sales are so important to the success of network and station operations that most top management positions are held by those who have moved up from the ranks of sales.

Traffic

The traffic department is responsible for organizing the flow of programming material and commercials. This department sees that commercials are aired at the right time, that films and other programs are available to be shown, that production work is done on time, and that each department is aware of programming and production deadlines. Traffic departments work closely with sales departments; they provide the salespersons with frequent updates of the commercial time that is available so that the sales staff can advise their clients of present availabilities.

Engineering

Engineers see that the station is operating in accordance with FCC technical standards. This includes keeping the broadcast tower lights on, maintaining transmitter power and frequency, checking heating and cooling systems, and ordering and repairing equipment.

Broadcast Standards

The networks all have departments that monitor programming and commercial acceptability. These departments serve a censorship function, and if they find any material unacceptable, they help producers and writers restructure the material so it will be suitable for the network. At individual stations, decisions about acceptability of broadcast material are usually made at the management level.

BROADCAST PROGRAMMING

The key to the success of any broadcast operation is its programming. The records, the news, the soap operas are all designed to attract the listener and the viewer to the broadcast media so that networks and stations can sell the audience to advertisers. Programming functions to bring the advertiser's message and the audience together. When a program attracts a large audience, advertising revenue increases; with a small audience, it decreases.

Prime time television programming is very expensive, so programs must at tract huge audiences to justify the advertiser's investments. An audience of only a million people would be considered a catastrophe at the networks-a weekly program series aired during prime time needs approximately 30 million viewers to be considered a success. However, the networks are not interested in just any thirty million households. The ideal audience for network prime time programming is considered to be between the ages of 18 and 49 and preferably female-these are the persons who do most of the buying of consumer goods in the American economy.

Market size is particularly important to network programming. If programming appeals to the top fifty markets, the broadcaster has a potential audience of most of the U.S. population. Since large markets contain the majority of the population, they are all in urban areas. Therefore, the urban population is more important to the programmers than the rural population. Also, advertising rates are much higher in the major markets. For example, the cost of a 30-second television commercial in a popular prime time program would be about $9000 at WCBS-TV in New York City; about $140 at KGGM-TV in Albuquerque; and approximately $80 at WWNY-TV in Watertown, New York. Thus, it be comes more efficient and more profitable for network broadcasters to direct programming to major markets than to minor ones.

Although major market radio stations are generally more profitable than minor market stations, market size is not nearly as crucial to radio as it is to tele vision. Radio stations program for a local rather than a national audience, and they generally depend on national advertisers for only a small share of their revenue. Radio stations sell most of their time to local advertisers, and the main concern of the advertiser is that the local audience will be persuaded to buy the advertiser's products. As with television, radio stations with the largest audiences are the most profitable.

Regardless of whether their audience and advertisers are national or local, all networks and stations have one thing in common; they constantly strive to develop programming that will attract the "right" audience for their advertisers. Even though some programming is considered enlightening, fascinating, and of tremendous social value by media critics, in the business of broadcasting it is a failure if it does not attract enough of the right kind of people.

Although no one has ever discovered a magic formula for successful programming, the broadcast industry makes certain program decisions- generally based on successful past experiences. In the section that follows we will discuss radio and television programs with regard to program sources, the selection process, and the program options that are available.

RADIO PROGRAMMING

When television became popular with the American public, it took away the large nationwide audience that had listened to radio. Television also absorbed much of radio's programming. Entertainers and comedians involved in program series soon realized that if they were going to survive, their future was with television, not with radio. Therefore, radio station management and program personnel realized they would have to develop new programming for mats. Music was the obvious choice since it appealed to the ear rather than to the eye, and by the late 1950s most radio stations had changed to an all-music format.

At the same time radio was making programming changes, it also had to change its way of making money. Since most national advertising had gone to television, the only way for radio stations to survive economically was to develop their local advertising sources. Radio time salespersons did precisely that, and although national advertising revenues to radio have remained constant, local advertising revenues rise every year. Radio formats largely depend on market size. Large market areas can sup port several stations with different formats, while a minor market may only be able to support one or two stations and, consequently, programming choice is limited. In a small market with a single radio station, the station will usually offer a combination of programs. In the morning, for example, a station might use a middle-of-the-road (MOR) format, which mainly consists of easy-listening music. In the afternoon and late evening, the station is likely to program contemporary / Top-40 music which will appeal to a young audience.

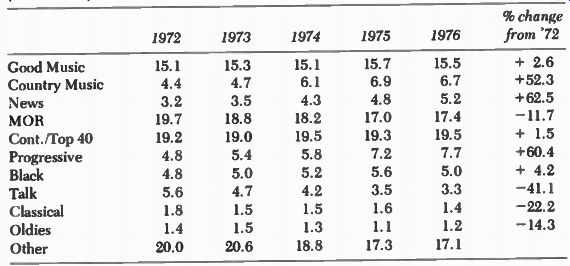

In larger market areas, stations program a single format. A medium market area is likely to have stations that use only Top-40 or MOR programming. In the largest markets, stations can offer even more choices. A typical Top- ten market may have stations that specialize in classical music, jazz, soul, or country music. As FM radio began to develop, there also came to be a number of "beautiful music" or "good music" stations--a term the broadcast industry uses to describe stations that play standard musical favorites. Although stations provide a variety of formats, listeners prefer contemporary/Top 40 followed by MOR-as can be seen in Table 4-3.

Programming specialization opened the door for advertising specialization.

MOR stations, for instance, often advertise banks and family-type restaurants, while Top-40 stations are more likely to advertise record stores and quick-food places. The more specialized the audience, the more specialized the advertiser becomes in trying to reach that audience.

TABLE 4 - 3 Trends in Radio Listening Preferences in the Top 25 Markets

(1972-1976) --- Source: Broadcasting, May 2, 1977, p. 51.

Today, most of the program formats for radio depend on music with occasional breaks for news. Many stations still receive news from the networks; other stations use the wire services and supplement this news with local reporting. Although some stations have all-news or all-talk formats, the mainstay of radio programming is music.

Stations that program MOR and "beautiful music" formats have uncomplicated program choices, since there is an identifiable list of music that appeals to their audiences. Even specialized music stations have little difficulty; there are only so many choices available in classical music, beautiful music, and jazz.

These stations have predictable formats, steady personnel, and consistent pro fits; all in all, they are the bread-and-butter stations of the radio industry.

The Top-40 stations are quite a different matter. They are the flashiest of the radio stations-their programming changes weekly, they have a great turnover of personnel, and they can make huge profits-both for themselves and for the record industry. Since they are unique, we would like to concentrate our discussion on Top-40 radio. Although some aspects of the business, such as playlists and trade magazines, are common to most radio stations, they take on a special importance for Top-40 radio.

Playlists. The most important programming element for an all-music radio station is the station's playlist, the lists of records the station plays each week.

These records are carefully selected by the program director, usually in consultation with his or her staff, and these are the only records that will be used during the life of the particular playlist. At a Top-40 station the total playlist contains an average of thirty-seven to thirty-eight records but only twelve to fourteen of these records get concentrated play. Although the list changes every week, it does not change very much. In a top-market station, the program director may replace only one or two records with recent releases. Since there are well over a hundred new releases every week, it becomes very difficult for a new record to get air time-especially a record by a new performer or group.

Program directors do not pick playlists haphazardly. They know that a successful playlist means higher ratings for the station. Therefore, in addition to consulting with the members of the station's staff, the director will usually seek outside information. The most important record information comes from the trade magazines, the tip-sheets, and the record promotion people.

Trade Magazines. There are three trade magazines for the record industry: Billboard, Cashbox, and Record World. Most people in the business consider Billboard to be the most influential and the best of the three. All of these magazines publish charts listing the top 100 records. They also indicate which records are moving up on the charts. Generally the trade magazines base these charts on record sales and information about playlists of stations throughout the country. These charts may be the single most important information source in the entire record industry. As one record executive puts it: "Every week the trades get hundreds of calls from artists, managers, and promotion people saying how tragically they erred in this week's list." Tip Sheets. Most program directors also subscribe to newsletters about singles records. These newsletters are called tip sheets, and the editors of these publications have correspondents at radio stations throughout the country who report on which records are rising and falling, and which records are being added to playlists in the correspondents communities. The best-known tip-sheets are The Gavin Report, Friday Morning Quarterback, the Tip Sheet, and the Hamilton Report.

Record Sales. Some radio stations periodically check with the major record stores to see which records are selling in their area. Record stores can be a useful source of information-especially about performers who have local and regional, rather than national, appeal.

All-Music Stations and the Record Industry. All-music programming turned out to be a boon for the record industry. All-music formats created a demand for a constant supply of new records, new performers, and new sounds. Usually only radio can create a hit single record, and every record company hopes that its record will be the one. Although at least 25,000 copies of a record must be sold before it can break even, record companies make a five-cent profit on every copy after that. Often a hit single inspires people to buy the performer's album-an even more profitable sale for the record company. Because of the potential value of radio exposure, record manufacturers provide free albums and singles to commercial radio stations. Stations located in larger markets often receive tapes of new songs even before the records have been pressed.

The tapes are duplicated from the master recording and distributed with the hope that advance exposure will improve sales of the new release. Because of the interest record companies have in promoting their records on the radio, stations receive albums and singles from the record companies every week.

Although stations pay nothing to the record companies, they pay annual fees to ASCAP (American Society of Composers, Authors, and Publishers) and BMI (Broadcast Music, Inc.), for music performance licensing. The fee that is paid to the two licensing organizations is usually in the form of a percentage of the station's gross billings for the year. It is, however, possible to pay on a per use basis for the use of records, but most stations have found the accounting problems of per-use charges so great that they simply settle for the amount based on gross billings.

Because of the value of radio coverage, record companies have devised many methods to encourage stations to play their records. One tactic has been the use of promotion people. Promotion people go directly to radio stations to promote their records. Although they try to get the major market stations to play new releases, they are generally unsuccessful because these stations do not want to take a chance with an unknown record. Therefore promotion people try for the secondary markets. If a record is played first in a number of secondary markets, promotion people may then be able to persuade stations in the major markets to play it. A good part of successful promotion is going from station to station and telling program directors who is playing what.

Payola

Some record manufacturers were less than satisfied with the results attained by legal methods of persuading disc jockeys to play their records. Consequently, they began to offer, and disc jockeys accepted, enormous fees to act as consultants to record companies. Favors such as free records, stereo systems, and money were given in return for playing the manufacturer's record releases.

During the late 1950s and the early 1960s, a Senate investigating committee discovered the practice of paying for the playing of records. As a result of the investigation, the Communications Act was amended to make the practice illegal.

The playlist system was instituted as a result of these scandals. When a station had a rigid playlist the air personalities had few opportunities to make record choices and hence they were not so vulnerable to temptations offered by the record companies.

Because the record companies depend on radio stations to create hit singles, station personnel are still not totally immune to bribes from record companies. During the 1970s, several payola scandals erupted again. At least one record company was accused of offering cocaine to station personnel, and several stations were offered bribes by concert promoters. Since it is so difficult to get a single on a playlist, small-scale payola scandals will probably continue to occur from time to time. Many performers and promotion people believe that if most records were only played, they would be successful. This belief makes it very tempting to offer bribes.

TELEVISION PROGRAMMING

Program Sources and Costs

The program sources that are available to television are both more complex and more varied than those sources available to radio stations. Stations that affiliate with a network have most of their programming problems solved; they get approximately 65 percent of their programs from the networks, 25 to 30 percent from program distributors called syndication companies, and they produce the remaining 5 to 10 percent themselves. Independent television stations have greater programming problems. They generally choose their programming from various program series that once ran on network television, as well as from motion pictures, free films, regional networks, and their own locally produced programming.

In this section we will discuss the three major sources-two local and one national--of program material, and some of the costs that are involved in producing programs for television. The local sources are local production and syndication, and the national source is networks.

Local Productions

The most common type of locally produced programming consists of news and public affairs programs. Since the FCC requires that stations meet the needs of their local communities, most television stations have decided to do this predominately through their news and public affairs programming. Local television stations are likely to have at least two or three local newscasts a day as well as one or two half-hour weekly programs about subjects that are of particular interest to their communities. Many stations also have a weekday morning program that is intended to attract a largely female audience. Stations vary greatly in local programming, but most of them stay away from programs that are purely entertainment, since the networks and independent production companies can do a much better job of providing that kind of program.

Syndication Companies

Syndication companies provide programs for stations to use when the stations are not receiving network programming. If the station is an independent, it gets most of its programming from syndicators. Syndicated programs are not carried on network lines; they are sent through the mail or by air or rail express to the individual stations.

Stations that obtain programs from syndicators have exclusive rights to show the programs in their markets. The price of the programs depend on the market size. Generally, stations buy several episodes of the program series and their contract with the syndication company specifies the number of times they can show the program.

Syndication companies provide both new and old programming. New pro grams are those which are produced specifically for syndication purposes.

Examples are "Hollywood Squares," the "Merv Griffin Show," "Let's Make a Deal," and the "Lawrence Welk Show." Old programming consists of feature films and off-network programs; that is, program series that have already been aired by the network. In order for an off-network program to go into syndication, it usually must have 120 episodes.

Off-network programming is a very profitable business. "Happy Days" was sold for $35,000 per episode to individual stations in major markets. Each station has the right to run each episode six times, beginning in the fall of 1979 when enough episodes are available for syndication.

Network Programming

Although networks supply about 65 percent of their affiliate's programming, they produce very few of the programs that they carry on their schedules.

Actual network production is limited to news, documentary, and sports pro grams, and talk shows such as the "Tonight" show.

The networks obtain the majority of their programming from independent production companies or the television divisions of Hollywood movie studios.

Although we associate prime time programming with the networks, almost all prime time programs are actually produced by these companies. Every independent production company or movie studio that works for television has the hope of selling a program series to one of the three networks. If the program is bought and attracts a large and faithful audience, both the independent production company and the networks make substantial profits.

The networks also buy the rights to show feature films that have already been shown in movie theaters. The more successful the film has been in the theater, the higher the price the network is willing to pay for the right to show it on television.

In the early days of television, advertisers provided many television pro grams. This practice meant that the advertiser also paid for all of the commercial time within the program. Since today's prices for commercials are so high, this practice of providing and sponsoring the entire program is not so common. Most advertisers prefer to spread their advertising dollars over a wide variety of programs in the hope of attracting as wide an audience as possible. An example of an advertiser that still owns and supplies television programs is Proctor and Gamble, which owns several soap operas.

Program Costs

One of the problems networks have had to face in recent years is the rapidly rising cost of the shows they buy from independent producers. In 1949 a typical one-hour drama could be produced for about $11,000; in 1961 a one-hour drama cost networks about $87,000, and by 1976 the cost was over $300,000. The costs of other types of programming have also risen rapidly. Because of these rising costs of production, networks have had to increase the cost of commercial time.

A consequence of high production costs has been a reduction in the number of new programs produced each year. Networks once purchased as many as thirty-six original episodes for each season a series was on the air, but rising costs caused networks to reduce the number of original episodes to as few as thirteen. Recently, networks have begun purchasing an average of twenty-four original episodes for a series. Thus, reruns start after only five months-in about February--and, with only twenty-four episodes produced per year, each one is shown on an average of about two and one-half times on the network in a year's time. Although many critics have protested the number of reruns, there is little reason to believe that shows will return to thirty-six episodes per season schedule. By showing each episode two or more times instead of creating new ones, networks are able to make a profit-something they often cannot do by only running the original episode.

The Selection Process

The process that networks use to reach a final decision on what programs they will buy from independent producers is a slow and risky one. A program idea is usually developed a good eighteen months prior to the time it actually appears on the air. At least 300 program ideas are considered by all the networks each year, but only a small percentage go into production and an even smaller percentage are actually successful once they are broadcast.

When a network believes that a program idea is promising, it commissions the production company to produce a pilot or demonstration program. Because of the high cost of pilots-each network spends about $20 million a year-net works resist paying for too many. 7 Once the pilot is produced, it undergoes extensive testing by the network. The network will air it in the season before it is to become a regular series in order to gauge public reaction; it will test show it in theatres and on cable systems, and it will be subjected to considerable scrutiny and modification by top network management.

If a pilot is judged acceptable after it has been tested and analyzed, it is considered for the following fall lineup. Network management must then decide where to put it in the broadcast schedule. Although management hopes that the pilot program will receive a good rating based on its own merits, it must also consider the programs that precede and follow it in order to get the highest possible rating for an entire evening's programming. A single program series is considered as only part of the entire schedule, and if the program can not fit into the schedule, it may be dropped.

Once the schedule is put together for the following fall, the networks get all of their affiliates together to view the new season's offerings. At such meetings, network executives promise gigantic improvements in the ratings, stars are brought in to mingle with station managers, and food and drink flow profusely.

Although affiliate station managers have the right to protest the networks' choices, which they often do, their complaints seldom bring about immediate change.

Once the affiliates know what will happen in the fall, the networks release stories about the forthcoming shows to TV Guide and other television-related magazines, hoping to build audience interest in the new season. In addition, during the summer "doldrum" months when sales are low, networks engage in elaborate self-promotion with unsold network commercial time.

Once the schedule is put together, the three networks combined will program about sixty-three hours of prime time programs a week and 135 hours in nonprime time periods during the week days. NBC programs more hours than the other two networks, since it programs talk shows into the early hours of the morning.

Types of Programming

Dramatic and Comedy Shows. The mainstay of prime time television is comedy and drama. This programming is also the most expensive to produce.

In the 1976-77 season "All in the Family" cost $170,000 and "Kojak" cost $340,000 for each episode (including the right to one re-run). Situation comedies have always been the leaders in ratings. Comedy in rural settings ("The Beverly Hillbillies") was big in the 1960s, but in the 1970s the trend has been more toward urban comedy, with programs such as "The Jeffersons" and "Good Times." Program preferences change in dramatic pro grams. At one time the broadcast schedule was filled with Westerns, but the latest trend has been toward situation comedies. The most common strategy in providing prime time programming for a new season is to imitate what has been the most popular program in a previous season, a process called "spin-offs" in the industry.

Mini Series. The 1976-77 season saw a new development in programming called the mini series, which is a series that presents a serialized novel in several episodes. The most successful of these series, "Roots," had the largest prime-time audience of the entire season. Mini series differ from regular series in that they have a limited number of episodes and are developed from best selling novels. Because of their success in the 1976-77 season, they are likely to become an established form of television programming in the years to come.

Feature Films. There are three types of feature films: old feature films that are generally shown in nonprime time; recent feature films that are shown in prime time; and made-for-television films. Made-for-television films are a fairly recent phenomenon. Although there has always been an audience for feature films, the television industry quickly used up all of the older films that had been shown in theaters. Their solution was to make films for television. Regardless of the type of film, networks pay an average of $900,000 to fill up a two-hour time slot with a film.

Specials. Specials are programs that are not part of a program series. They are intended to be shown only one time and they are known in the industry as O.T.O.s, or "one-time-only's." They are, however, subject to being rerun, as is any prime time program. Specials appear in many different forms. Generally they bring us programming that would be too expensive or too specialized to produce in a regular program series. They may be dramatic (such as the Hall mark specials), they may be documentary (such as the network news specials), or they may take on a cartoon format, as do some of the children's programming shown around the holiday seasons.

Variety Shows. Although variety shows were very popular in the early days of television they have generally decreased in recent program schedules. The present variety show is usually organized around well known performers such as Carol Burnett. An episode of a variety show is often not re-run which makes its cost even higher because the network has to pay for a replacement. In 1976-77 an average episode of the "Carol Burnett Show" cost $265,000.

News. Each network news operation employs hundreds of people and has a yearly budget of millions of dollars. Most of the budget and personnel go toward producing the evening news program, although a certain percentage will also go toward the documentaries that are aired on the networks.

Local stations also have news staffs that cover the local community. Although a major market station might have a news staff that numbers as many as twenty or thirty people, stations in small or medium markets might have only four or five people, and they are often also involved in other programming at their station.

Both stations and networks depend on the wire services for news. The two national wire services are Associated Press and United Press International.

Both of these services have reporters throughout the United States and the world to provide written news, commentary, headlines, weather reports, and even photographs. In order to obtain the special equipment necessary to receive these services, the stations and networks pay a subscription fee to the news services.

Sports. Since sports often attract large audiences they are very profitable to the networks. Networks occasionally carry regularly scheduled sports but they are more likely to offer special sports events as they occur. An important game brings great financial reward to the network. For example, in 1976 an estimated 73 million people watched the Super Bowl. A one minute commercial for the program cost $230,000! Game and Quiz Shows. Although quiz shows were very popular in prime time programming in the 1950s they were withdrawn from the air when Congress discovered that producers were rigging the questions so that certain contestants would win. The quiz shows were replaced by game shows in which people were asked to perform stunts rather than answer questions. In the 1970s quiz shows reappeared in nonprime time with much smaller prizes.

Game and quiz shows are commonly found in both daytime and early evening programming. Compared to prime time program costs, they are very cheap to produce-about $25,000 for half an hour.

Soap Operas. Soap operas, more respectfully known as daytime drama, are often owned and produced by the advertisers. Although the ratings are low compared to prime time, the audience is very faithful. Soap operas are also one of the cheapest forms of programming. For example, it costs NBC $170,000 to produce an entire week of "Days of Our Lives," while the daily advertising revenues are $120,000.

Children's Programs. Children's programming is most commonly found on Saturday mornings, but since National Association of Broadcasters, under pressure from the FCC, recently created the family viewing hour (from 7:00-9:00 PM) programs that are free of excessive sex and violence can be seen nightly. The Saturday morning programming always makes a profit for the networks.

Religious Programming. Most religious programming comes from the networks or from church-related organizations that have programs in syndication.

Stations often charge these groups to carry syndicated programming. Religious programming is most often carried on Sunday morning-a time which is of little interest to the advertisers.

CONCLUSION: CHANGE AND THE FUTURE

As we have seen from the preceding discussion, the ownership patterns and the programming practices in the broadcast industry are organized in a way to make the broadcasting business as profitable as possible. Since the present system is profitable, the broadcast industry works to preserve the status quo. However, the system does change from time to time.

Changes in programming are most likely to come about because the industry discovers that some new form of programming is more profitable than the old. The best examples of this type of change are situation comedies that have social themes. When Lucille Ball's real life pregnancy also provided a story-line for "I Love Lucy" in 1953, the industry proceeded with great caution and hired script consultants from several religious organizations to make certain that her pregnancy was not presented in an offensive manner. By the 1970s, however, similar situation comedies were dealing with social problems that ranged from impotency to alcoholism. "All in the Family" was the first program to try any of these subjects, but when it became clear that this program attracted huge audiences several other programs quickly followed with controversial subject matter of their own. Similarly, persons who appeared on the television screen became more varied-especially during the 1970s. For instance, several major market stations hired both black people and women to take anchor positions on local news programs. When it became clear that the presence of these individuals did not hurt the ratings-indeed they often improved ratings--other stations were quick to follow. Obviously, this sort of change cannot take place unless a station or a network is willing to take the first risk. But broadcasters must take a certain number of risks, since it is clear that the same type of programming will not continue to attract audiences indefinitely.

Ownership patterns are not likely to change as quickly as programming pat terns. Station ownership is most likely to change hands only when a station is losing money-a situation that is more likely to occur in a minor market than a major one. During the 1970s, however, both the Justice Department and citizens' groups have been working to break up current ownership patterns.

Their efforts seem to indicate that if change is to occur in ownership, it is more likely to come from external forces than from forces within the broadcast industry.

Since the broadcast industry is organized according to a profit-maximizing model that is common to almost all other businesses in the United States, dramatic change is not likely to occur. Since this sort of change is not imminent, it remains practical and realistic to analyze the broadcast industry as a business enterprise with economic motivations; in short, broadcasting is a business.

NOTES

1. A Primer on the Economic Structure of Television," Access, 20 ( October 6,1975), pp. 11-12.

2. Walter S. Baer, et al., Concentration of Mass Media Ownership: Assessing the State of Current Knowledge (Santa Monica, Calif.: The Rand Corporation, 1974), p. 47.

3. Ibid., pp. 2-3.

4. Broadcasting Yearbook 1976 (Washington, D. C.: Broadcasting Publications Inc., 1976) p. A-43; and Richard Bunce, Television in the Corporate Interest (New York: Praeger, 1976), p. 103.

5. Media Report to Women (Washington, D. C.: Media Report to Women, 1975), 2:3, pp.

6. Access, 20, op. cit., p. 9.

7. Baer, op. cit., p. 143.

8. David Halberstam, "CBS: The Power and the Profits," Atlantic (January 1976), pp. 33-71.

9. New York Times (May 9, 1977), p. 57M.

10. Broadcasting Yearbook 1976, pp. D17-D28.

11. FCC, Thirty-ninth Annual Report, p. 234.

12. Access, 20, op. cit., p. 10.

13. John Blair and Company, 1975 Statistical Trends in Broadcasting, 11th Edition, (New York: Blair Television Blair Radio, 1975), p. 41.

14. Clive Davis, Clive: Inside the Record Business (New York: William Morrow, 1975), p. 200.

15. Broadcasting (January 10, 1977), pp. 34-36.

16. Broadcasting, April 26, 1976, pp. 28-29.

17. Bob Shanks, The Cool Fire: How to Make it in Television, (New York: W.W. Norton, 1976), p. 104.

18. Broadcasting, (April 26, 1976), pp. 28-29.

19. Ibid.

20. Broadcasting Yearbook 1976, p. A-2.

21. Stephanie Harrington, "To Tell the Truth, the Price is Right," New York Times Magazine (August 3, 1975), p. 17.

22. "Sex and Suffering in the Afternoon," Time, (January 12), 1976, p. 47.