By Tony Lee

In this era of momentous electronic breakthroughs in communications and medical science, it might be understandable that we could forget that not many years ago, people in many parts of the world struggled to survive.

While it is true that some of these people still struggle to overcome their adversities, it is worth noting here, the part that early radio communication and the indomitable perseverance of pioneers in radio communication, like John Flynn, Alf Traeger and others led the way to a new world of hope and development in the Australian "Outback".

John Flynn, the founder of the Australian Flying Doctor Service, envisaged a "Mantle of Safety" over the entire outback--a sun-burnt, inhospitable region covering an area of 5,000,000 square miles.

In 1918, he knew little of aviation and still less about radio communication but he was quick to realize that without a radio network in the outback, it would be virtually impossible to administer medical assistance to the isolated cattle and sheep stations (ranches), and other outposts.

In those days, it wasn't uncommon for a ranch hand to travel two or three hundred miles on horseback to summon help, only to find the doctor out of town attending another patient at another far-flung outpost.

In many cases, medical advice alone would have been sufficient to prolong the life of a sick child until professional help arrived. But health and safety were not the only concern of Flynn. On his frequent visits to the outback, he saw the crushing effect of isolation and loneliness on the outback community. Women in particular suffered from deprivation and fear when their men-folk were away for weeks or months at a time, mustering or driving stock to the railhead.

Quite often, calls for medical help arose from nothing more than a debilitating aberration. Sturdy, healthy bush men broke down. Some found escape in alcohol, others in suicide ... all for the sound of a human voice! Radio telephony was in its infancy in the early twenties. Throughout Europe and Britain, there were only six radio telephone stations in operation. Some outback Australian towns had telegraph offices, and telephone lines had been installed along railroad tracks but for long-distance communication, the transmission of a message was agonizingly slow and tedious.

When a young ranch-hand sustained serious internal injuries when he was thrown from his horse, he was taken in a buckboard the forty-seven miles to an outpost telegraph office. The operator could not contact the nearest doctor 250 miles away so he tapped out a message to a Perth doctor through 2,283 miles of telephone wire.

Because of the inferior batteries of that period, messages had to be relayed through several telegraph stations at the maximum permissible speed of 25 words a minute. The recipient listened to the telegraph sounder and recorded the message in long-hand. No priority was given to emergency messages over regular telegrams.

Joe Flynn's plan was to establish a radio network across the outback, using base stations attached to hospital and aerial transport facilities. Each base or mother station would reach out to a number of isolated habitations installed with tranceivers.

He reviewed the state-of-the-art as it was at that time and three major systems emerged, each at a different state of development. Communication began with the electric telegraph which relied on miles of wire to transmit and receive messages, and used a Morse key, a sounder and a battery.

Simple though it was, the installation of wires connecting hundreds of outlying communities was not a viable proposition. But much progress had been made in the field of radio telegraphy. Although it still depended on Morse code as the means of transmitting and receiving a message, the system dispensed with wires which proved a quantum leap forward in the search for the ideal "outback" communication service.

The earliest designs employed spark transmission.

Hertz, Marconi and others had demonstrated how the low-voltage primary winding of an induction coil could produce a high-tension spark in the secondary coil.

This in turn could produce electro-magnetic waves in an aerial coil which radiated out from the aerial like the ripples from a stone thrown into a pond.

A receiver at some distance away could pick up the signals by using an aerial of similar length. Later experiments enabled the receiver to be tuned to the same wavelength using adjustable aerial coils, and this was further refined with an adjustable condenser The spark-gap transmitter was later replaced by the far more efficient oscillator design which employed Lee De Forest's triode, the first amplifying vacuum tube invented, and Edwin Armstrong's regenerative circuit.

Not only did it produce a purer tone for Morse reception compared with the staccato buzz of a spark gap, but it required far less input power to achieve a greater transmission range. This was indeed another step forward of major significance.

The third and unquestionably the most important development was the radio telephone, capable of voice transmission but fraught with obstacles.

In 1918, the radio (or wireless) telephone was limited to the armed forces, some merchant shipping and a few amateur experimenters. The 'wireless" enthusiasts had reported to Flynn that equipment was available with a range of 300 miles. Sadly, this was not the case.

The best portable equipment developed by the R.A.F. had a range of only thirty miles.

Another published report stated: "There are now on the market some very compact machines, capable of transport on the backs of two horses!" This was certainly not what Flynn had in mind. His goal was to provide the outback folk with a long-range, low powered sturdy, cheap set, easy to operate and easy to maintain. He was ahead of his time.

The first Atlantic broadcast by radio telephony in 1915 used 300 vacuum tubes! The apparatus was clumsy and fragile, prone to breakdown and consumed enormous power, and electric power was one commodity the "outback" folk didn't possess. A "portable" radio telephone of that era required the equivalent of six car batteries to power it. It also needed a stable high-tension supply for its continuous carrier wave to ensure reliable transmission.

Joe Flynn had to contend with all these issues and decide on the best approach. If he was to gain support and raise funds for his ambitious program, he would need to demonstrate the practicality of it. His immediate objective therefore was to set up a mother station capable of servicing several outposts.

Because of the complexity of radio telephony, he opted for radio telegraphic equipment for the outposts and radio telephony at the base station.

It would be difficult enough for the amateur operators at the homestead (ranch-house) to send Morse code, let alone receive it. This made sense since it would enable the Flying Doctor or other personnel to speak directly to a patient using headphones or a loudspeaker, and give comfort and advice.

Flynn had made many friends amongst the wireless fraternity, many of whom were amateur radio operators and backyard hobbyists. It wasn't long after Marconi sent his first Morse signal across the Atlantic that the "backyarders" were communicating with each other across the length and breadth of Australia. Perhaps it was Australia's geographical isolation that placed it in the forefront of communication development.

Flynn had made many friends amongst the wireless fraternity, many of whom were radio operators and backyard hobbyists. It wasn't long after Marconi sent his first Morse signal across the Atlantic that the "backyarders" were communicating with each other across the length and breadth of Australia. Perhaps it was Australia's geographical isolation that placed it in the forefront of communication development.

Whatever the reason, tribute must be paid to the amateurs who, with the restrictions placed on them by the "professionals", made such strides in the 100-Meter band. While the professionals grappled with their medium and long wavebands of 300 to 3000 Meters, using massive power to achieve the greatest distance, the shortwave brotherhood with their low-power, less complex home-made equipment, were getting remarkable results. Max Howden, a "ham" operator in Melbourne was the first to send a radio signal to be picked up in England.

above: Alf Traeger about 1930, demonstrating his pedal generator and transceiver.

The equipment can be seen in the Flying Doctor Museum at Alice Springs

in Central Australia.

Amateurs around the world were in contact with each other well before the professional stations, notwithstanding the limitation imposed of 25 Watts maximum output. With clever aerial arrays and transmitting at night when the Heavy-side layer supposedly comes closer to Earth, they achieved maximum range.

But in the early 1920's, the wireless devote3's could not provide Flynn with a transceiver suitable for outback conditions.

The problems relating to portability, power supply and reliability seemed insurmountable. And then Flynn met Alf Traeger, a gifted young electrical engineer and holder of an amateur radio operators license. He joined forces with Flynn and together they made several sorties to the outback, with Flynn's battered Dodge truck weighed down with radio apparatus, aerial masts and spare parts. But their experiments were unsuccessful and Traeger returned to his workshop in Adelaide.

First he made extensive modifications to the receiver and came up with a low-powered design using only two vacuum tubes. The low voltage batteries were lightweight and had a life expectancy of at least four months. Clarity through headphones or a loudspeaker was excellent under "normal" outback conditions. The difficulties previously encountered appeared to be resolved.

Clarity through headphones or a loudspeaker was excellent under "normal" outback conditions. The difficulties previously encountered appeared to be resolved.

But there was still the seemingly insoluble problem of power for the transmitter. Batteries were out of the question and most outposts could not afford the luxury of a generator driven by a gasoline engine. Traeger had already experimented with a hand-operated generator, using a quartz crystal to smooth the manual input but although it performed reasonably well, it required two operators; one to crank the generator, the other to operate the Morse key and adjust the receiver.

And then came the breakthrough he had been searching for-the pedal-operated generator that was to give a voice to the outback. He built an oil-filled gearbox to which he attached the cranks and pedals from a bicycle. At the top of the gearbox he mounted the generator which supplied the twenty watts required by the transmitter. It was a resounding success. With no more effort than riding a bicycle on a flat surface, an operator could generate the power while tapping out the message.

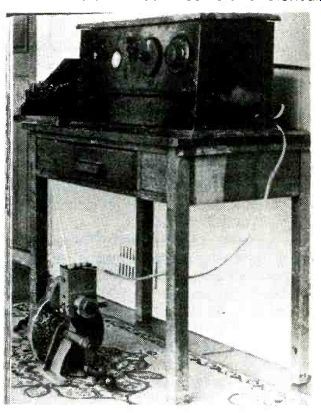

Above: the pedal radio generator, developed by Alf Tfaeger, which solved

the power problem at remote habitations in the early twenties.

Armed with six sets of radio transceivers and pedal generators, Traeger set out for Cloncurry, a remote town in far-north Queensland, to establish the first radio network for the Flying Doctor Service--an area of 90,000 square miles.

There was no time to lose before the wet season set in, and with the help of the newly appointed radio operator, Harry Kinzbrunner, he installed the base station at Cloncurry. A Lister gasoline engine in a shed at the back of the small church ran the generator for the 200 watt telephony transmitter, which was installed in the vestry. After carrying out some tests, he left Kinzbrunner at the base station and headed for the first outpost, Augusta Downs Station 180 miles north of Cloncurry.

above: Traeger's complete "outback" transceiver. Note the keyboard on

the left of the cabinet. It dispensed with the need to learn and transmit

Morse code.

Accompanied by George Scott (a Patrol Padre from the Inland Mission) as his assistant, Traeger installed the pedal radio, as it became known, and erected the sixty-foot aerial mast. Then he taught the wife of the station manager to use the Morse key and operate the controls.

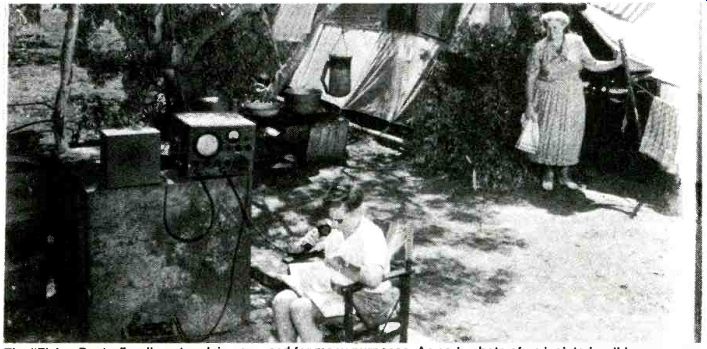

The little girl waits with the pedal generator while her mother jots down

a message from the "Flying Doctor." The photo was taken in the

early 1940's after the radio telephone had replaced radio telegraphy.

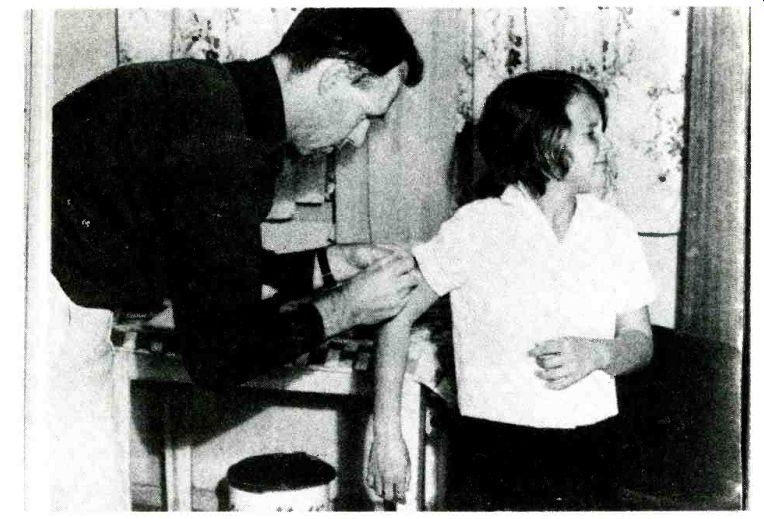

The expression says it all! A visiting "Flying Doctor" immunizes

a child on a cattle station.

Ten days of preparation and Traeger was ready to contact Kinzbrunner who was standing by. The excited family and ranch-hands crowded around the transceiver; Mrs. Rothery waiting with her hand on the Morse key.

She turned nervously to Traeger and asked, "What shall I send?" Try sending `Hello Harry, he suggested.

The story goes that Kinzbrunner received the message: "Hell OHell OHarry!" It caused much amusement among the outback community but it was an historic moment and one that Flynn would have been proud of.

Unfortunately, he was on a world tour at the time; financed by his aviation and radio friends. But before he left, he agreed that it would be advisable to instruct the womenfolk on the operation of the radio equipment because they seldom left the homestead and were often left alone with the children.

Traeger went on to install the other five pedal radio's at outposts hundreds of miles apart, and it was after leaving the fourth that tragedy struck. Sister Gilbert, a nurse working on one of the most remote outposts in Australia--Birdsville, became ill. She and her colleagues had been teaching themselves Morse code for weeks prior to Traeger's visit but when they went to use the transmitter, they found it defective.

They drove Sister Gilbert to the nearest telephone-250 miles away and called Cloncurry. But the weather conditions made it too hazardous for flying so they drove the 150 miles to Cloncurry where she was operated on but died soon after. The rigors of the journey along bush tracks had taken its toll; 400 miles of heat and dust... Nevertheless, the pilot project proved a huge success and the first Flying Doctor aircraft, appropriately named "Victory" went into service. News of the incredible pedal radio spread through the outback in a very short time and orders came pouring in from far and wide.

It wasn't long before the radio network was being used for other purposes as Flynn had intended. Outback communities could listen to talks, music and news broadcasts besides the essential medical advice. In fact, the outback folk often received news from America and Britain before the city newspapers got it! But Alf Traeger wasn't content to rest on his successes. While constructing, installing and servicing the equipment, he was forever trying to improve the efficiency and reliability of it.

Between bickering with the bureaucrats at the Post Office about not keeping up with written specifications on each outpost station (even though they were all the same), and teaching the ladies to send Morse code, he was, in his own words, "Running around the country like an agitated ant!"

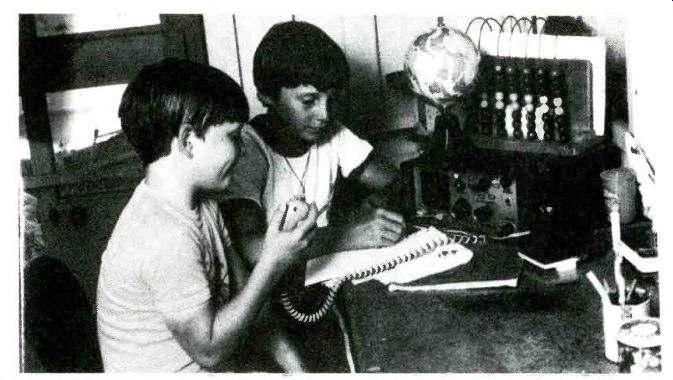

The "outback" radio network enabled the establishment of the "School

of the Air," the world's largest classroom.

These children on a cattle ranch chat with their teacher and classmates hundreds of miles away.

Many of the pedal radio operators were not proficient at sending clearcut, unambiguous messages which caused considerable hardship for the base radio operator who had to decipher them or ask for a repeat.

Traeger thought long and hard about the problem and the feasibility of building an "automatic Keyboard." Using the principle of a typewriter, he cut the lettered key bars to correspond to the dots and dashes and intervals of Morse code. When the keys were pressed, they energized a relay which opened or closed the transmission circuit.

Whether a portable typewriter was modified for the prototype of his ingenious invention, is not clear but it worked very efficiently, if rather slowly. Operators no longer had to learn the tedious Morse code and laboriously tap out messages.

By 1934, Traeger had built and installed approximately seventy of his keyboards but by then, he was busily converting telegraphic stations to telephony and they were swiftly phased out from then on.

The Flying Doctor Service now provides a "Mantle of Safety" across the vast interior of Australia, using the most up-to-date single sideband radio transmission equipment available.

The old pedal generators have long been supplanted by electrical power or generators that can charge batteries or directly power the transceiver. The compact, low-maintenance SSB transceivers can now be found in several thousand outposts scattered over the continent. And there are now a dozen or more base stations to service them.

There is no place in Australia where the Flying Doctor Service can't reach a sick or injured person within two hours. Only the old-timers can reminisce about the days when the women-folk had to travel several hundred miles by camel through floods, dust storms, torrential rains and incessant heat to have their babies.

Thanks are due to the founder, John Flynn and his many helpers and advisers, not the least Hudson Fysh, the aviation pioneer and co-founder of Qantas Airways; Harry Kauper, chief engineer of the Australian Broadcasting Commission; and the intrepid band of amateurs, the unsung hero's of short wave communication development. But above all, Alf Traeger who was awarded the Order of the British Empire for his "unstinting contribution" to the Flying Doctor Service. Almost up to his passing in 1980 at the age of 85, he continued working in his Adelaide factory, advancing the science of communication.

-------- The "Flying Doctor" radio network is now used

for many purposes. An early photo of an isolated well-borers camp shows

a pupil "attending" the School of the Air...the worlds largest

classroom. Mom looks on with pride.

Also see:

adapted from: Electronics Handbook 1992