(source: Electronics World, Dec. 1963)

By JOHN R. COLLINS

When certain molecules are excited by electromagnetic radiations, they change energy levels. When they drop back to their previous levels, they give up energy. This is basis for masers, lasers, atomic clocks.

SEVERAL striking developments in the past few years have advanced electronics in a sort of quantum jump-to use an expression that is becoming commonplace. It is especially appropriate here because many new devices are outgrowths of the quantum theory, which, although more than half a century old, is just beginning to be exploited.

The most familiar of the new quantum devices are the maser and laser, which embody entirely new principles of amplification for microwaves and light rays. In addition, there are molecular and atomic clocks with accuracies better than 1 second in 40 years, the tunnel diode which can amplify or oscillate in the giga-cycle region, and certain spectrometers capable of making detailed chemical analysis of compounds by electronic means.

Much of the quantum theory is hard to visualize or to represent with mechanical models. Electronics has come a long way since water tanks represented voltage, narrow pipes portrayed resistors, and walking on a garden hose illustrated modulation of d.c. with a.c. Moreover, the quantum theory is not a single rule like Ohm's Law, but an accumulation of information about the atom that fills many volumes. While the theory is definitely an area for specialists, its impact on modern electronics has been so great that no technician who wants to understand the newest equipment can afford to remain ignorant of this phenomenon.

Energy Levels

Conventional electron devices, such as electron tubes, function by means of the effect of an electrostatic field on the movement of charged particles, usually electrons. Quantum devices, however, utilize changes that take place inside particles owing to the effect of an electromagnetic field on their internal structure. The particles may be either molecules, atoms, or ions. In the following discussion, the term molecule is used to denote any of the three kinds of particles.

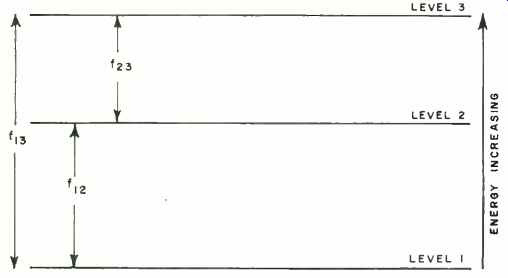

Molecules are made up of electrons and atomic nuclei which, according to the quantum theory, can assume only certain fixed motions and orientations. Each set of motions or orientations is associated with a discrete amount of internal energy called the "energy level" ( Fig. 1) . At any given instant, a molecule may be at any one of a number of possible energy levels. It cannot exist anywhere in between. The fact that it jumps from one level to another is the origin of the so-called quantum jump. When a molecule jumps from a lower to a higher energy level, it absorbs energy and is said to become excited. When it drops to a lower level, it gives up energy.

A natural question is, "What takes place inside the molecule when energy is absorbed or emitted ?" There is no simple answer to explain all changes in energy levels. In some instances, the absorption of energy is accompanied by the transition of an electron from its usual orbit to a new orbit more remote from the nucleus. An equal amount of energy is emitted when the electron returns to its original orbit.

A second type of transition involves atoms having unpaired electrons. Each individual electron may be viewed as a small, spinning magnet with a north and south pole. In most substances, electrons are paired off with their poles opposite to each other, so that their magnetic fields are cancelled. In a few substances, however, cancellation is incomplete, leaving an unpaired electron in each atom.

When such substances are placed in a magnetic field, the unpaired electrons can have just one of two positions-a lower energy state in which the electron's north pole points in the direction of the magnetic field, or a higher energy state in which its south pole is in the direction of the field.

The frequency at which energy is absorbed or emitted in this kind of transition is directly proportional to the strength of the external magnetic field.

In a third case, energy transitions may be accompanied by changes in the relative positions of elements making up a molecule. The ammonia molecule (NH3), for example, is shaped like a pyramid, with an atom of nitrogen at the apex and a hydrogen atom at each of the three corners of the base.

When excited, the nitrogen atom apparently drops through the base to the other side, inverting the pyramid.

Regardless of the reasons, however, the important point is that molecules will absorb and emit energy in fixed amounts, and the transition from one level to another is not smooth, but takes on the appearance of a jump.

Planck's Constant

Although the absorption and emission of energy by various substances had been observed for some time, it was not until 1900 that Max Planck made the important discovery that a fixed relationship exists between the energy and the frequency of the radiation. At the time Planck was studying radiation of energy from a hot object. He noted that the amount of radiant energy emitted at each wavelength from the ultraviolet to the infrared could be obtained by multiplying the frequency of the radiation by a constant amount of h, equal to 4.13 x 10^-15 electron–volt-second. His discovery is expressed by the formula E = hf where E in this case stands for energy, not voltage, and f is frequency.

Just as Einstein found a way of expressing energy in terms of mass, Planck's formula provides a means of expressing energy in terms of frequency. Although the theory started with Planck, its further development was carried out by many of the greatest scientists and physicists of this century, including Einstein, Pauli, Rutherford, and Heisenberg. It was soon found that Planck's formula applies not only to energy emitted from a hot object, but to the entire electromagnetic spectrum. It should be noted that Planck's constant is exceedingly small and therefore the amount of energy involved becomes appreciable only at the upper end of the spectrum--that is, in the region of microwaves, x-rays, and light.

Since h is a constant, Planck's formula implies that energy E is always absorbed or emitted in discrete packets or quanta which are called photons. A photon is equal to the product of its characteristic frequency f and the constant h. Since frequency may vary over a wide range, all photons are obviously not of equal energy. However, in no case is energy emitted or absorbed in a fraction of a photon.

Spontaneous and Stimulated Emission

Under ordinary circumstances, some of the particles in any substance will be at a higher energy level and some at a lower level at any given tune. Particles are raised to a higher level by heat, light, electron bombardment, etc. They will naturally revert to a lower level after a period of time, and in doing so spontaneously release photons. These photons may strike other molecules and cause them to jump to a higher level in turn.

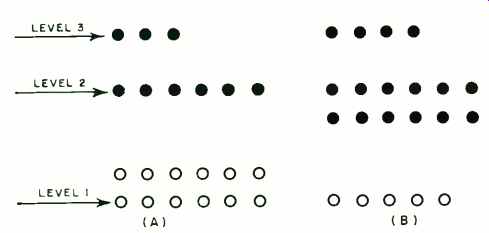

Fig. 1. Among the three energy levels in a molecule, the energy difference

between each level is related to characteristic frequency. For example,

f_23 is the frequency corresponding to energy difference between levels

3 and 2.

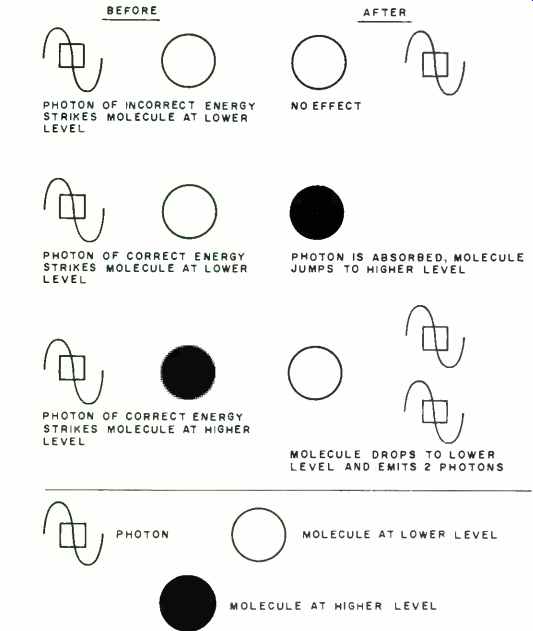

Fig. 2. Rules for the interaction of molecules with photons.

Fig. 1 shows, in diagram form, the energy levels that might be found in a molecule. Each transition from one level to another would be accompanied by absorption or emission of radiant energy of a characteristic frequency. If f_23 represents the frequency of the radiation absorbed or emitted in a transition between levels 2 and 3, we can determine the energy E_23 involved from the relation: E_23 =hf_23. Similarly, if we know the energy of the photons emitted, we can find the frequency by rearranging Planck's formula to: f_23 = E_23/ h.

The time required for a molecule in a higher state to revert spontaneously to a lower state depends on the kind of molecule and the type of transition involved. The probability of a transition taking place may be greatly increased or stimulated by the presence of radiation of the required characteristic frequency. The greater the density of this radiation, the greater the probability that a transition will occur.

Fig. 2 shows how molecules react with electromagnetic radiation of the characteristic frequency. It is important to note that a photon of the correct frequency (or energy) striking a molecule at the lower energy level will cause it to jump to a higher level. However, if a photon of the sane energy strikes a molecule already in the higher energy state, the molecule will revert to the lower state and two photons will be emitted. It is this characteristic that makes possible the amplification of microwaves and light by masers and by both solid-state and gas lasers.

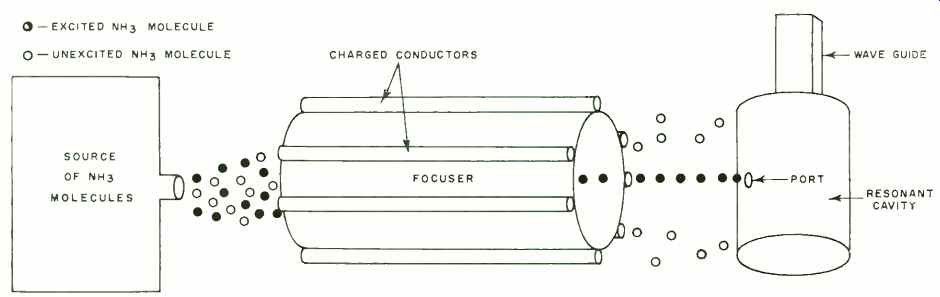

Fig. 3. Excited ammonia molecules are separated from unexcited molecules

to form the basis of an ammonia frequency standard.

The Ammonia Clock

One of the first practical applications of the above principles was the molecular clock using the ammonia molecule.

This molecule has two energy levels separated by a gap corresponding to 23,870 mc. Ammonia has the unusual property that at the lower level the molecule is attracted by an electrostatic field, while at the higher level it is repelled.

Fig. 3 shows how this characteristic is used to separate high-energy molecules from a mixture. Ammonia gas containing both excited and unexcited molecules is emitted from a source at high pressure and is passed in a narrow stream through a focuser. The focuser is made up of a system of charged conductors that provide a strong electrostatic field.

The low-energy molecules are attracted by the conductors and are thus dispersed along the sides of the focuser. The high-energy molecules, however, are repelled by the conductors and are therefore concentrated in a narrow beam at the very center of the focuser. They are thus directed into the narrow port of a resonant cavity while the low-energy types are deflected aside.

The dimensions of the cavity are exactly proportioned to make it resonant at precisely 23,870 mc. This tends to reinforce the oscillations which occur at that frequency as the molecules drop to the lower energy level, so that a strong signal is generated. This signal is conducted from the cavity by a waveguide. The flow of energized ammonia molecules into the cavity is regulated at the level necessary to make up for losses and sustain oscillations. The output is a frequency of 23,870 mc. of the utmost purity, with no sidebands or noise and serves as a precise frequency or time standard.

Masers and Lasers

It was pointed out previously that if radiation of the proper frequency strikes a molecule in the excited state, the output will be two photons of the same frequency. Therefore, if enough molecules are in an excited state when struck by these photons, the result will be the amplification at the characteristic frequency. The apparatus for accomplishing this is the maser-an acronym standing for microwave amplification by stimulated emission of radiation.

Solids are usually employed for masers since their molecules are more concentrated than those of gases. Early masers were two-level devices in which molecules were excited by "pumping" with radiation corresponding to the transition frequency. Such masers could amplify a signal only during the interval between pumping and spontaneous relaxation.

This difficulty was solved by the three-level maser (Fig. 4). Normally, most molecules are at the lowest level, the fewest at the highest level. The pumping frequency corresponds to the energy difference between levels 1 and 3, so that molecules are transferred from the lowest to the highest level.

During the relaxation period they drop in about equal numbers to levels 2 and 1.

If the pumping radiation is strong enough, more molecules can be kept in level 2 than in level 1, and the frequency corresponding to the energy difference between levels 1 and 2 can be used for amplification. Since this frequency is different from the pump frequency, the apparatus can 'be operated as a continuous amplifier.

A resonant cavity is used in the case of the ammonia clock, and cryogenic equipment is employed to reduce noise. Noise level is extremely low, so that masers may be used to amplify very weak signals, such as those encountered in radio telescopes and long-distance radar.

The laser (light amplification by stimulated emission of radiation) is closely related to the maser and requires little additional comment. It was recognized that light could be amplified in the same way as microwaves, provided that the energy difference between two energy levels corresponds to a frequency in the light region of the spectrum. Because of the short wavelength of light, the problem of devising a resonant cavity was formidable. This difficulty was overcome, however, by using mirrored surfaces at the end of the laser crystal.

Fig. 4. Distribution of molecules in a 3-energy level maser. (A) shows

normal distribution before pumping where most molecules are in the lowest

energy level and fewest in the highest level. In (B), molecules pumped

from level 1 to level 3 fall back to either level 1 or level 2 so that

the total number in level 2 exceeds the number that are present in level

1.

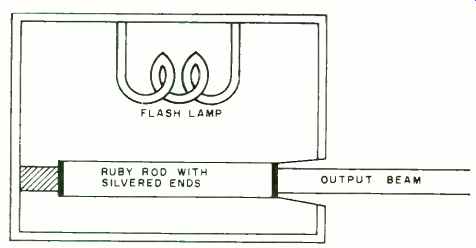

Fig. 5. When a chromium-doped ruby rod is excited by the intense light

from a flash-lamp, it emits a red, coherent light.

The test setup is shown in Fig. 5. A ruby crystal, composed of aluminum oxide and containing a small percent of chromium oxide which causes its red color, is formed in a rod several inches long. One end is completely silvered to give full reflection, the other with a very thin coating so that some light will pass through it.

A brilliant flash lamp pumps the chromium atoms to a higher energy level. Laser action begins when one of the energized atoms spontaneously emits a photon in the direction of one of the mirrored ends. Emission in other directions passes through the side of the rod and has little effect. However, emission in the direction of one of the mirrors sets up a chain reaction as photons bounce back and forth between the mirrored surfaces, striking other energized atoms in the process and causing each to emit two photons.

When amplification is great enough, a narrow beam of extremely intense red light is emitted from the partially silvered end of the rod. The light is coherent, covering a single frequency, and provides a striking demonstration of the operation of the quantum theory.

The laser is finding wide use in medical, chemical, and biological research, and may be the principal means of communications for space vehicles. Lasers may also lead to the design of very-high-resolution radar systems.

Spectrometers

The quantum theory has provided two new kinds of spectrometers, called the nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) and the electron paramagnetic resonance (EPR) spectrometer. The first type uses the gyro-magnetic properties of atomic nuclei, the second the orientation of unpaired electrons. Electromagnetic radiation is provided by a combination of an r.f. signal and a strong magnetic field. The r.f. signal is usually maintained at a constant level while the magnetic field is usually increased.

Energy is absorbed from the system at resonance points that correspond to energy level transitions. Since these are different for each kind of atom making up the unknown sample, the composition can be determined by measuring the density of the magnetic field at the points where absorption occurs. The degree of energy absorption is related to the number of atoms involved, so both a qualitative and quantitative analysis is provided.

An r.f. signal of about 10 kc. is usually employed for NMR spectrometers. Since EPR spectrometers are designed to take advantage of fields associated with unpaired electrons which resonate at much higher frequencies than atomic nuclei, it is necessary to use microwave plumbing.

The above descriptions cover some of he more important quantum devices.

The list is not exhaustive, as quantum mechanics is influencing much current developmental work. In view of the successes already attained, there is reason o believe the quantum theory will be a major factor in invention for many years to come.