|

|

(source: Electronics World, May 1971)

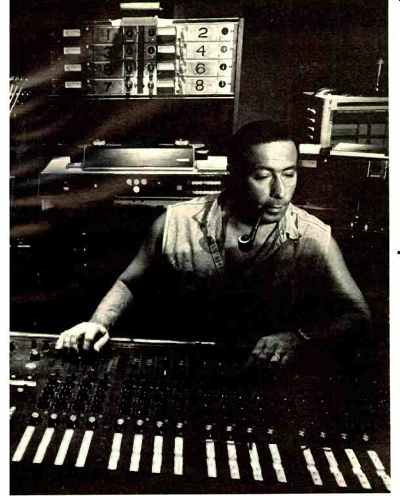

By FRED CATERO /Chief Engineer, Filmore Corp.

Present methods of recording classical material often do not have the quality of live performances achieved by jazz /rock recordings. Greater use of multichannel recording techniques may be the answer.

---- Above: The author, shown adjusting knobs of control console during mix-down

session, does complete engineering, dubbing, mixing and sound effects for records

made and published by the Filmore Corporation. For all recording assignments

he uses multichannel recorders, including Ampex's MM-1000-8 and-16.

TRADITIONALLY, classical music represents one of the highest forms of musical expression. Its combination of sounds, emotion, and complexity of composition make years of preparation and study mandatory for its execution, or even its appreciation. The harmonic spectrum of classical music is the basis for many of the other musical forms which have evolved during the past four centuries. Although other types of music have enthusiastic adherents, by world-wide consensus, the audience for classical music is the largest and most enduring.

Recently, it has become increasingly clear that, in some respects, the classical music world is lagging behind jazz/ rock. The fault lies not with the quality of classical music performances, which remain consistently high, but in the way they are being recorded.

The classical music tradition has also proved a hindrance to its progress. The proliferation of taped music makes classical recordings of all types available to a whole new audience. However, current methods of recording classical tapes do not always provide the live-performance quality such listeners have been used to with their jazz/ rock recordings. One reason is that jazz and rock are being recorded using multichannel techniques, while classical discs are not.

Multichannel recording of jazz /rock allows pure sounds to be captured, original sounds to be enhanced, and errors to be corrected. These advantages are obvious when comparing classical and jazz /rock recordings with their live performances. The jazz /rock (multichannel) recording can faithfully recreate, and frequently enhance, the live performance whereas a classical recording invariably falls short of a true "concert-hall" effect.

A brief review of classical recording methods will pinpoint just where multichannel techniques could be used to improve such recordings.

The objectives of the classical recording engineer differ from those of the jazz /rock engineer. The latter wants to separate instruments while recording so that sound effects, corrections, and various sound impressions can be added later. On the other hand, the classical engineer tries to record the orchestral performance as faithfully as possible.

While both want a fine product, the classical engineer is not permitted the technical flexibility which multichannel recorders offer the jazz /rock engineer.

Unlike the jazz /rock engineer, the classical engineer has very few cues to watch for in controlling volume. The volume, which could be accurately measured by instruments, is the province of the conductor. The instruments for a classical recording are as traditionally positioned as the keys of a typewriter, so it is the conductor who ultimately controls the volume. Thus, the engineer is left to record sounds as they are played.

The number of tracks used in classical recording makes it virtually impossible to recreate a true "concert hall" effect.

Classical recordings have been made with 3- and 4-track recorders since 3-track mastering began in the late 1940's. The 3-track concept is the one used most frequently with one track left, one center, and one right.

Such recorders give the engineer a practical limit of four inputs per channel. In most cases, this means that he has 12 or, at most, 16 microphones with which to cover up to 150 instruments, a chorus, sound effects, audience noises, etc. In most symphony orchestras, the four basic instrumental sections (strings, woodwinds, brass, and percussion) may involve 80 or more people who are miked (two microphones spaced every 15 feet) not for isolation /separation but for "fullness" of sound. To gain this effect, instrumentalists are sometimes added or the volume is increased.

Quite a bit of leakage results from using 12 to 16 loosely positioned microphones recording section-by-section instead of by instrument type or specific instrument. With this technique, much specific audio information is lost in the general tonal leakage. Isolation screens are seldom used-except for a vocalist being swamped by the orchestra or for bringing forward the delicate sounds of the harpsichord, etc.

Responsibility for volume balance and tonal control is usually divided among the recording director, the conductor, and the instrumentalists. At studio rehearsals, just prior to taping the actual recording, the orchestra will make two or three takes. The director, score in hand, will carefully follow the movement, note corrections to be made, and advise the conductor. The conductor then assumes responsibility for recording the movement properly.

While the performance is in progress, the conductor must correct any errors (and prevent their repetition), and achieve a mix suitable for the final master tape. This process could be handled more efficiently and easily electronically. The orchestra-it goes without saying-is expected to perform flawlessly, but this is not always the case.

Meanwhile the engineer's involvement has consisted of setting up and balancing microphones. He does a minimum amount of mixing, only that which is crucial to the final two-track stereo master.

The final master may have tonal or instrumental errors or sound-effect deficiencies-the singer may be inaudible, a cue may be missed, a cymbal may have entered too soon, or the acoustics of the concert hall or studio may be too live or too dead. These are mishaps which could ruin an otherwise commendable performance.

Because of retakes, many classical recordings can be extremely costly to make yet not give an accurate representation of the original performance.

Classical recordings also represent a great waste of the technical capabilities of the engineer and fail to take advantage of the sophisticated recording equipment available to him.

The application of multichannel recording (8 or 16 tracks) would eliminate most, if not all, the problems involved in making classical recordings.

It would be legitimate to use three tracks for the stereo effect (left, center, right), one or two tracks for soloists, one track for the chorus, one track for sound effects, one or two tracks for instrument isolation, one track for director /conductor instructions and editing purposes, and one additional track for instrumental corrections. This means using at least an 8-track recorder which could provide audio information as well as volume and mix control not previously available to the conductor, director, or engineer once the initial take was over.

With the multichannel recorder, such common situations as a great orchestral performance but poor voice reproduction, poor instrumental balance, timing errors in rhythm or sound effects, or a singer out of balance, could be eliminated from the recording.

Multichannel recorders could eliminate costly repeats during a final taping session-something that often occurs when a singer's voice cracks, a violin string breaks, or a music stand gets knocked over. By using 8- and 16-track recorders with selective synchronization, a performer can listen to the playback of one track while recording on another, so a part that was ruined during the final taping can be redone without having to reassemble the orchestra and repeat the performance.

Here are a few worthwhile tips: Record by instrument type and objective; isolate each section, allowing one or more tracks as needed to achieve the proper effect with no leakage; pre-mix and balance, putting different instruments on different tracks so that correct emphasis can be placed on a desired instrument or sound effect during the final mix-down; use roughly 15 to 25 microphones and mike close-to to achieve a pure sound without having woodwinds or strings drowned out by the brass or percussion sections. This sound can be greatly enhanced by the skillful addition of reverberation, equalization, compression sound limiting, panning, and various other effects.

Multichannel recording would not detract from the "feel" of the recorded performance as heard by those listening to a disc or tape, but it would insure that everything that should be heard on the disc will be audible.

Also see: