SOURCES OF INCOME

Every month somebody has to pay the bills. This is true for a radio station, just as it is for any other business enterprise. There is a payroll to meet, rent to be paid, equipment to be repaired, materials to be purchased, and numerous other expenses. A radio station is expensive to operate, and it must have a substantial source of income. Let us look at some of the ways a station might sustain itself.

A station may be commercial or noncommercial

If it is licensed as a commercial station it is permitted to sell advertising time. It can sell the time in "blocks" of 30 minutes or an hour; or it can sell short spot announcements. Most stations choose to sell their time in short spots of 30 seconds or a minute. These spot announcements are distributed throughout the broadcast day. Commercial stations employ sales representatives to find advertisers who wish to buy time on the station. The person performing this job may be a local time salesperson, or a national representative. The local time salesperson deals with the merchants of the local community; the national representative handles the big accounts that are advertised nationally. Sales is one of the most important aspects of commercial operation.

A noncommercial station is not permitted to sell advertising. The terms of the license specifically state that money can not be received for the endorsement of a commercial product. The noncommercial station must therefore find other ways to obtain the income that is required for day-to-day operation. In this Section we will look in some detail at the means of financing both commercial and noncommercial stations.

COMMERCIAL STATIONS

Most broadcasting stations are commercial and financed by revenue received from advertisers who buy air time. In the early days of radio this air time was available in "blocks" consisting of 5-, 10-, 15-, 30-, and 60 -minute segments. Sponsors would buy blocks of time and produce their own programs to fit. The programs were often carried on a network and featured big -name personalities. In between the programs, stations would run short "spot" announcements, sometimes called "station break" or "chain break" spots. The demise of "block" programming was the result of several factors: television consumed almost all of the big name drama and comedy programs; independent stations (not affiliated with networks) began to spring up; radio went to a music-news format; and station owners saw the value of maintaining a consistent "sound" throughout the day, rather than jumping from one type of program to another. So it is now the local radio station owner, rather than the advertiser, who determines the content of the programming. Sponsors who wish to buy time have control of the material in their advertisement, but that is all. They may write the copy and have it produced by an outside agency, but they have little if any say over the program into which it is inserted. A station owner may make an effort to accommodate an advertiser who wants to sign a long-term contract but has to take into consideration the other sponsors who may also be buying time in the same segment. What is more, the broadcaster must also be in touch with the listeners' tastes and desires. A station does not gain much if it wins a sponsor but loses the audience.

THE SALES STAFF

Your chances of breaking into the profession of broadcasting are good if you have the ability to sell. All too often students overlook this aspect of the business, when actually it is the most promising. Not only will you earn more money as a salesperson than as a disk jockey, but the hours will be better too. The person who has the best chance of being hired is the one who can do a combination of things. If you can write copy, operate the equipment so that you can record your own spots, announce, and also bring in accounts, you can be a very valuable member of any radio broadcasting staff.

Your success as a salesperson will be determined by a number of factors: the popularity of the station, the number of people who listen, the ratings, the promotion campaigns, the type of programming offered, the quality of the announcers, and of course, the cost of the spot announcements.

The Local Sales Representative

Every commercial station has a sales staff headed by a sales manager.

The number of sales personnel employed will depend upon the size of the station and the size of the community. Usually the salesperson works on a commission basis, earning approximately 15 percent of the "billing." Often the people in the sales department are the highest-paid members of the staff. The local sales representative contacts the merchants in the community and tries to persuade them to buy spot announcements.

He or she will try to get them on a long-term contract if possible by pointing out that the cost per spot is less if the maximum is purchased.

(See the Rate Card.) Personality characteristics and techniques used by the radio time salesperson are similar to those found in any other area of selling.

The National Representative In addition to the local accounts, radio stations need to obtain business from large, national advertisers. To do this, it is necessary to have contacts in all the major cities, and normally a small, local station would not have sufficient money or resources. So, to acquire the large accounts, a station will contract with a national representative. This is a company that specializes in acquiring for local stations the big national accounts. A national rep will deal with the agencies that handle the advertising for products distributed nationwide. This is something you may want to take into consideration if you plan to apply for a job as a salesperson. Much of the advertising that is done by stations in large metropolitan markets is handled by the national reps. Therefore, the local time salesperson in a major market may not have as much opportunity as the sales representative in a smaller market.

THE RATE CARD

Suppose you are the one who determines the cost of each spot announcement. How are you going to know what to charge? A simple answer would be "whatever the traffic will bear," and that would not be far wrong. Your rate might be determined by what an advertiser is willing to pay, but it might also reflect your cost of operation. To compute this, take your total cost of operation for a full year. That would include salaries, rent, taxes, depreciation on equipment, maintenance, office sup plies, promotion costs, lawyers' fees, custodial service-everything. Divide that by 365 to get the cost of operation for one day. Then decide how many spot announcements you want to run per day. You may be tempted to say, "as many as I can sell." For a number of reasons, unfortunately, you cannot use that as a guide. First, because the National Association of Broadcasters' Radio Code specifies that there shall be no more than 18 minutes of commercial time per hour. And the FCC will expect you to abide by that. Second, because the number of spots you sell will depend to a large extent upon how much you charge for each one. And third, because your listening audience will diminish if you run too many commercials. So you have some choices to make. You can keep your operating costs down so that you could afford to run few commercials in an effort to build your listening audience. As you do that, you will gradually be able to increase the cost of each spot. If it turns out that your station is not taking in enough revenue to meet expenses, you must either cut your overhead, increase the cost of your spot announcements, or sell more of them. Suppose you need to earn $800 a day to meet all of your expenses. If you wanted to run two hundred spots per day, you could sell them for only four dollars. But you would probably want to run only one hundred per day and sell them for eight dollars. Better still, run only fifty and sell each one for sixteen dollars.

Consider too, that during some hours of the day you will have more listeners than at others. You will be able to charge more for the spots that run during peak traffic periods. Most stations divide the day into two or three classes and charge premium rates for high priority times.

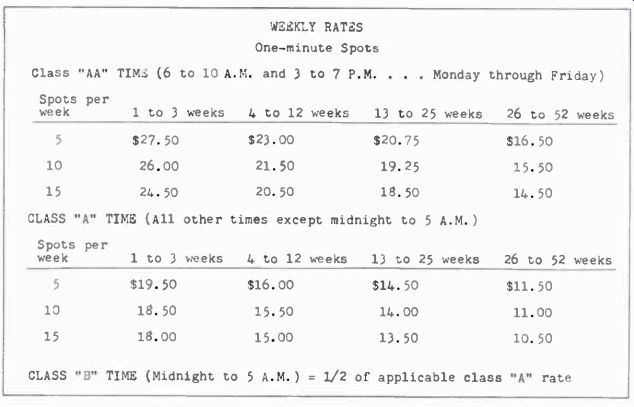

The length of the spot will also affect the cost. Most spots are either 30 seconds or a minute; occasionally there will be 15-second spots too. In addition, a station may offer a frequency discount. This means that the more spots an advertiser contracts for, the smaller the cost per spot. All of this may sound very confusing, so in order to make it understandable to a potential advertiser, a station will print what it calls a rate card. A typical one is shown in FIG. 1.

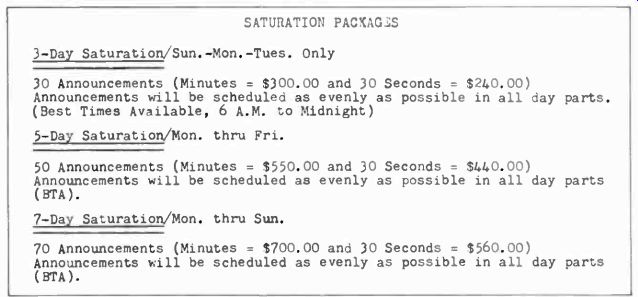

The rate card is easy enough to read. If the sponsor buys five 60-second spots to be run in 1 to 3 weeks during class AA time, the cost is $27.50 per spot. At fifteen spots per week over a 52 -week period, the same spot costs only $14.50. Advertisers know that buying as few as five radio spots does practically no good at all; announcements must be purchased in some quantity in order to be effective. Generally a sponsor will select one or more stations which reach the audience desired and run several spots a day over a long period of time. Occasionally the sponsor will have a big event, such as a sale or the introduction of a new product, and will want to saturate the market for just a few days. For these occasions a station may offer the sponsor saturation packages (see FIG. 2).

FIG. 1 Rate card

FIG. 2 Saturation package.

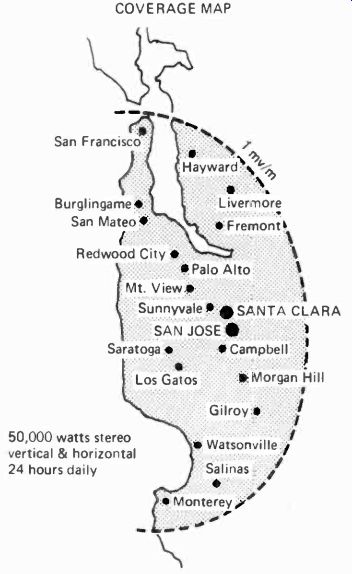

The rate card may also include a map showing the station's area of coverage. With 50,000 watts this San Jose station shown in FIG. 3 gets good coverage of the South San Francisco Bay Region.

But how does an advertiser know what station to buy? And how do you, as an advertising salesperson, let your client know that your station will do some good? You have little that is tangible when you are selling air time. The advertiser could use the trial-and-error method, but it is difficult to know whether or not the announcement running on your station is bringing in any business. From time to time customers may say that they heard an announcement on the radio, but that is not a reliable index. Holding contests or making special offers to radio listeners is another method of gauging response, but a company would not want to do that all the time. An advertiser may rely upon personal taste and instinct, but that is a bit unscientific. To a large extent, salespersons will be selling their energy, creativeness, and concern for clients. They will service their accounts regularly-that is, call upon clients often and make sure that the commercial copy is up to date. Advertisers do not like to be forgotten about once they have signed contracts. A salesperson knows that in order to keep an account, the client must believe that the advertisements are doing some good.

1.

Demographics are sociological characteristics that include ethnic background, economic status, religious affiliation, and many other factors in addition to age and sex.

AUDIENCE SURVEY REPORTS

The most reliable evidence that a salesperson has to work with are audience survey reports. These do not tell the advertiser how many customers a spot announcement is bringing, but they do show how many people were exposed to the message. Moreover, the survey will show the demo graphics' of the audience. Age and sex are the two factors that seem to be the most significant. An advertiser may be interested in reaching a male audience between 18 and 25, and so, will select a station which attracts that particular segment of listeners.

One of the most widely used audience survey reports is Arbitron Radio. It collects its data by issuing diaries to a carefully selected cross section of a given population. The people who agree to keep the diaries record their radio listening in quarter-hour segments for a period of several weeks. The returns are assembled, published, and distributed to broadcasting stations which have contracted for the service. The "Book" is expensive, but it is valuable to the broadcaster. It provides evidence that can be shown to sponsors to demonstrate the effectiveness of the station. Even stations that are low in the report can use the survey to their advantage. For example, the low -rated station can show that it charges less for its spot announcements and has a lower cost per listener than its competitor. Other stations may take pride in the fact that they have the highest ratings in a particular time period or for a particular audience segment. This may be more important than the overall cumulative rating.

FIG. 3 Coverage map (Courtesy KARA )

Rating and Share In looking at audience survey reports you must distinguish between the rating and the share. To compute a rating, you need two numbers: the total population and the number of people who have listened to a particular station.

Number of listeners

Total population-rating (%) There are two kinds of ratings. Average-quarter-hour ratings tell you what percentage of the total population was listening during an average quarter hour in a given time period. Cumulative ratings tell you what percent age of the total population listened at least once during the time period measured. In other words one person may have listened to 8 quarter hours of one station over a 4 -hour period. The average -quarter-hour persons for the 4 -hour period would be one half of a listener because there are 16 quarter hours in a 4 -hour period. Each quarter hour is counted separately; the person would have to have listened in all of the quarter-hour segments to be counted as one full listener. If one person represents five hundred in the survey, (one person contacted out of every five hundred) the formula would be:

(500 x 8 quarter hours) -1- 16 = 250 average -quarter-hour persons

This would then be divided by the total population to give the average-quarter-hour rating. If there are 10,000 people in the total population, the formula would be:

250 10,000- 0.025 or an average -quarter-hour rating of 2.5%

Now let's look at cumulative ratings. In this case each person is counted only once for listening at any time during the 4 -hour period. So the cumulative ratings will be higher even though the number of listeners is the same. Again, consider the one person who represents 500 in our survey. If that person listened at any time during the 4 -hour period we compute the cumulative ratings as follows:

500- 0.05 or a cumulative rating of 5% W(A)

It is understandable why stations prefer to talk in terms of "cume" (cumulative) ratings rather than average-quarter-hour ratings.

The share of the audience is the ratio of the number of listeners to the number of stations to which they were listening. Or, another way of saying it: share is the average number of persons who listen to a station during a given quarter hour, expressed as a percentage of all persons who listened to radio during the time period measured. To calculate share you need two numbers: the total listening audience during a particular quarter-hour segment, and the number of people listening to a particular station in that quarter-hour segment.

Number of people listening to a particular station / Total number of people listening to all stations =share of audience for a particular station

It is important to distinguish between share and rating. Both are shown in percent, but they should not be confused or interchanged.

Remember that rating always relates to the total population, whereas audience share is the percentage of people listening to the radio. Let's say, for example, that a station has a ten percent share of the audience in the morning, and a twenty percent share at night. This means that the station is doing better at night in comparison to other stations even though there may be more people listening in the morning hours. The ratings for all stations may go down, but you are in good shape if your share of the audience continues to be high. The rating is important to advertisers, though, because it tells them how many people their messages are reaching. In this way they can calculate how much it is costing them to reach each listener.

NONCOMMERCIAL STATIONS

A noncommercial station is one that may not receive payment for advertising goods and services. It is issued a license by the Federal Communications Commission specifically stating that no charge may be made for the promotion or endorsement of commercial products. Usually people operate these stations for reasons other than the profit motive. They may feel, for example, that the cultural enrichment of the community is not being provided by the commercial stations. They may wish to offer certain types of programming, such as drama or classical music, which are often not scheduled by the commercial stations. The reason may also be to provide broadcasting experience for those wishing to enter the field.

But whatever their reasons may be, they have to have some means of raising revenue other than selling commercials. There are several possibilities open to them.

Listener Support

There are several radio and television stations in this country that are supported primarily by money contributed by listeners. This is a tenuous means of financing a station. It requires broad coverage and loyal listeners. Stations that use this method sometimes find themselves in a dilemma. Their main purpose is to provide alternative programming (that which appeals to a minority of listeners), but at the same time they must attract an audience large enough to provide adequate support. In addition they must devote a certain amount of their air time to making appeals for money which in some cases can be as offensive as commercials.

Corporation for Public Broadcasting

This is a private, nonprofit corporation that was established to implement the Public Broadcasting Act of 1967. Through government and private financing, it makes funds available to noncommercial radio and television stations. CPB does not directly produce radio programs, but it does provide grants to stations for various purposes. It helps new stations get on the air and assists in the expansion of existing ones. A radio station would not rely totally upon CPB for support; it would look for other means of financing as well.

National Public Radio

Stations which are eligible for CPB funding may receive and broadcast programs produced by National Public Radio. NPR has extensive resources to which a local station would not have access. This provides a means for noncommercial stations to compete in quality and coverage with the large commercial networks.

Institutional Support

Many noncommercial stations are financed by institutions such as schools and churches. Just like all other stations, they must abide by the rules of the Fairness Doctrine and not espouse their cause to the exclusion of others. They are useful in providing their parent institutions with a voice to publicize important messages and activities. Colleges often support broadcasting stations for the purpose of offering a training ground for students and a means of reaching a large segment of the community. A station funded by an institution is relieved of the need to make appeals to the public for donations.

Underwriting

This is a method of financing available to all non commercial stations. It permits the broadcaster to mention the name of a commercial organization that has provided funding for the support of the station. This is allowed under FCC Rules and Regulations as long as certain criteria are met. 2 No product may be endorsed by the station; you may not urge people to buy from, or even visit, any establishment. You may give only the name of the company-not its address, phone number, or even a description of its merchandise. The announcement may appear once at the beginning and once at the end of the program. Usually it is phrased in the following manner: "This program is made possible through a grant from the corporation." Public radio and television stations can make good use of this method of financing. Companies are, of course, allowed to deduct the donation from their income taxes, and in addition they get their names out to the public. Underwriting is popular among large corporations eager to improve their public image and to let people know they are supporting community affairs.

SUMMARY

Every station needs to be financed in some way. Most commercial stations are able to make a substantial profit by selling advertisements. The young person thinking of going into the broadcasting field should seriously consider radio sales; salaries and commissions are higher in that area than in any other area of broadcasting. The amount that a station can charge for its spot announcements is closely related to the number of listeners it has. In the metropolitan areas, stations compete fiercely for high ratings. The higher the rating the more a station can charge for its announcements, and the better the chance the salesperson has to sell air time. Noncommercial stations do not have to compete in the "numbers game." They are not under as much pressure, but they also are generally forced to operate on much smaller budgets.

TERMINOLOGY

Average-quarter-hour ratings

Book

Block programming

Chain break spots

Class A time

CPB (Corporation for Public Broadcasting)

Cumes (cumulative ratings)

Demographics

Frequency discount

Fringe area

National representative (national rep)

NPR (National Public Radio)

Rate card

Rating

Saturation

Share

Underwriting

ACTIVITIES

1. Contact a commercial station in your local area and ask to see the rate card.

Talk with the sales manager and ask how long the rates have been in effect and what makes them go up or down. Specifically, ask how much the survey reports affect the station's rates. Ask if you can see a copy of the most recent ratings, and see how the station stands in popularity compared to the other stations in the area. Find out what the station considers to be its strongest selling point.

2. Contact a noncommercial station and ask if they have an underwriting pro gram. If so, find out how they obtain contributors and how much of the station's total revenue is provided by underwriting contracts.

3. There are 300,000 people in a station's listening radius. A survey company contacted 1,000 people, so each contact represents 300 people. One hundred of them said they had listened to a particular station at least once during a 4-hour period. What is the station's cumulative rating during that period? Those same 100 people said they listened to 6 of the 16 quarter hours in that time period. What is the average -quarter-hour rating for that time period?

4. Count the number of commercials during prime time on an AM radio station.

Compare that to the number of commercials during prime time on an FM station.