The Commodores "Easy" like $60 million, by Steven X. Rea

Studio Circuit Back in the home studio: The 52,000 difference, by Bennett Evans

Report from the Winter NAMM Less hype, more substance, by Fred Miller

Pop-Pourri "Rock & Roll for a Desert Island", by Stephen Holden

Zevon Strikes Again, by Crispin Cioe

Records: The Clash, The Ramones, Cecil Taylor

Breakaway Bruce Woolley, musical Frankenstein by Steven X. Rea

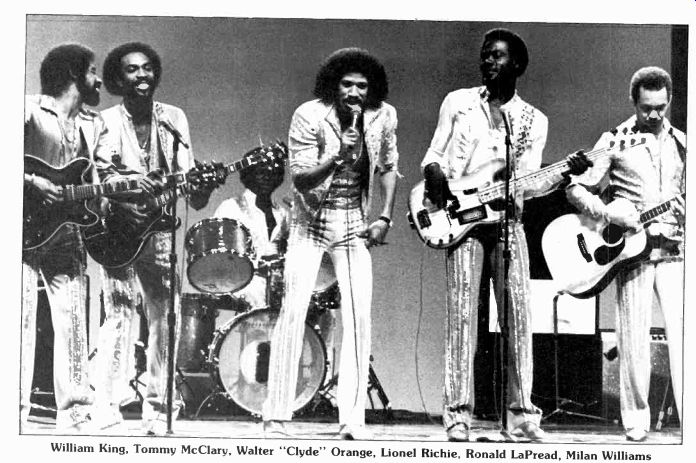

The Commodores: "Easy" like $60Million by Steven X. Rea

--- William King, Tommy McClary, Walter "Clyde" Orange,

Lionel Richie, Ronald LaPread, Milan Williams.

Tommy, McClary, his white Adidas pressed up against the sound-booth glass, sits in an insulated cubicle adjoining the studio control room eliciting a succession of country licks from the acoustic guitar on his lap. He is overdubbing a part for the intro to Wake Up Children, a song on the Commodores' newest LP, sched uled for April release. Reclining behind the 24-track console at Motown's Holly wood studio, the group's co-producer James Carmichael-a wry, wizened black man in his middle forties-lights another in a seemingly endless chain of cigarettes, pushes his glasses up along his nose, and shakes his head ruefully. "Tommy, that sounds like some kind of slide guitar or something. What are you doin'?" "I know it does, I know," McClary says, grinning back through the thick sheet of glass that separates the two rooms. Engineers Calvin Harris and Jane Clark and drummer Walter " Clyde" Orange exchange amused glances, as if to say, "Uh oh, here comes another argument." Carmichael's credits span two decades as an arranger, conductor, and ghost musician for such Motown acts as the Jackson 5 and Diana Ross & the Supremes. He has guided the Commodores through six years of hit records, starting in '74 with the disco/funk Machine Gun and continuing with numerous pop, r&b, and crossover hits, such as the r&b rocker Brick House, the soul ballad Three Times a Lady, and the out-and-out country bal lads Easy and Sail On, last year's huge single.

Past country success or no, right now a slide guitar seems to be too much for Carmichael to cope with. McClary enters the control room to hear the play back, after which an amicable but spirited debate between the producer and the tall, thirty-year-old Commodore ensues.

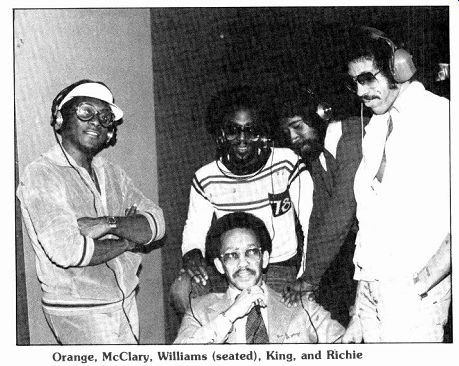

---- Orange, McClary, Williams (seated), King, and Richie

"It's like the Eagles do it," McClary says, alluding to his overlay of a country motif on a rock setting. (The Commodores frequently cite such unlikely stylistic influences; others include Elton John, the Beatles, and Bob Dylan.) "Uh huh," Carmichael nods doubtfully.

Pianist, saxist, and lead vocalist Lionel Richie walks in and listens to the track. "Mr. Motown," McClary teases, "doesn't think this intro sounds right." Some quiet discussion leads the decision to sit with the thing for a while.' Wake Up Children is one of twelve tracks being recorded for the Commodores' tenth Motown album. The material runs the gamut from hard rock to folk to gospel and includes such titles as Heroes, Mind Spirit, Jesus Is Love, and Sleazy.

Wake Up Children, written by Richie and McClary, builds from its slow, resonant ring of acoustic piano and guitars to an amalgam of country blues, hard rock, and gospel. "It's probably the first Commodores song to have political overtones," comments McClary.

Though the vocals have yet to be recorded-they are usually the final stage of the group's recording process-the track is an ambitious piece about which the band is, to say the least, enthusiastic.

Thirty-one-year-old William King, who plays keyboards, percussion, and trumpet, comments: "Richie's doing things with his voice that we've never heard be fore. He sounds like Mick Jagger." "We've always tried to do something different with each album," says soft-spoken keyboard ist Milan Williams. "On our new one, we've gone beyond ourselves." "We don't usually have a title or a cover concept until maybe a month before the album's due," says Richie. But a concerted effort has been made to concentrate on the album in toto this time, as op posed to the song by song approach they've taken in the past. Even though "Midnight Magic," the Commodores' last LP, garnered three Top 10 singles, won the American Music Award for Favorite Soul Album, and has been nominated for a Grammy, they feel it had some weak spots. This time around they are endeavoring to produce a cohesive album.

The Commodores' ability to move records is unarguable, but because their label only recently became affiliated with the Recording Industry Association of America (which monitors and certifies sales) there's no official tally of the band's sales to date. According to Motown, all nine of their albums have gone gold (500,000 units) and several have reached triple platinum status (3 million). World wide record sales are put in the vicinity of $60 million.

In 1968, McClary, Richie, and King-all business majors at Alabama's Tuskegee Institute-formed a band called the Mighty Mystics, covering tunes such as Tobacco Road and James Brown's Cold Sweat. Williams, an engineering major, was playing keyboards in a band called the Jays. Soon after the Mighty Mystics and the Jays heard each other perform at a freshman talent show, they joined forces to form the nucleus of the Commodores.

Orange, the only music major in the bunch, replaced the original drummer, Andre Callahan, and Ronald LaPread, an other engineering major, replaced bassist Michael Gilbert. Since late 1968 that lineup has remained unchanged. Frat par ties, club dates on the "chitlins circuit," and all-white debutante dances followed.

From the beginning the Commodores have placed a strong emphasis on "commercialism" and "versatility," playing hits by pop acts like Three Dog Night as well as Sam Cooke scorchers. Those early decisions have paid off: Today their concerts draw an almost equal number of blacks and whites.

This broad-based appeal no doubt comes from their very diverse back grounds as well. Richie and LaPread are Tuskegee natives, King is from Birming ham, Orange and McClary from Florida, and Williams from Mississippi. Because of their Southern black roots, the Commodores' musical heritage encompasses the '60s Motown sound, r&b, gospel, and rural blues. And Richie, whose grandmother was a classical music teacher, grew up listening to Bach, Beethoven, and Mozart; his uncle, Bertram Richie, was one of Duke Ellington's arrangers. Add to these an impatient finger on the radio dial, and that brings country & western, jazz, and Top 40 to bear on Richie's context.

"People always want to tag us," he says, "by citing James Brown and the Temptations as our main influences. But we also grew up in a pop environment. We listened to the Beatles, Jimi Hendrix, Led Zeppelin, Glen Campbell, and Merle Haggard as much as we listened to Brown. We consider ourselves a pop band playing popular music. We're not just a soul act or a country act or a disco act." Even the awards they've received have been diverse: They were Billboard's Top Soul Album Artists (and Top Box Office Artists) and Rolling Stone's Soul Group of the Year in 1978, and Record World named them Top Male Group, Top Crossover Group, and Top Album-Selling Group. In that same year, Three Times a Lady won ASCAP's Country Songwriter Award and the American Music Award for Best Pop Single.

All of that is a far cry from the rather unspectacular results of their first and only-LP on Atlantic, which was recorded in one day by eccentric r&b artist Swamp Dog (Jerry Williams). "Swamp Dog was our introduction to 'big time' record producers," King recalls laughing.

"The first time we met him, he had on a green suit, green shirt, green socks, green shoes, and a green hat." The album's sole single release was a cover of Shorty Long's Keep on Dancing (now a collector's item).

Fortunately they had run into entrepreneur Benny Ashburn while performing at Harlem's Smalls Paradise in 1969, and he took control following the Atlantic fiasco. Ashburn, who has been their man ager ever since, takes only a one-seventh share of the group's profits, whereas most managers slice off up to one-quarter. Now in his mid-fifties, his first move as "the seventh Commodore" was to book them as the ballroom band on an S.S. France cruise to Europe. "We played one show over and one show back," recalls McClary.

"It gave us a chance to play for all kinds of people. We did things like Wichita Line man. We even did the Theme from Love Story!" It was when they hit the European stages, though, without an album or any previous familiarity, that they knew they had it. The success of their show, choreographed by King, proved them masters at working an audience. In fact since campus days, their emphasis has been on live performance, and Richie says he writes his songs with a show, not a record, in mind.

The group returned from their modest but triumphant 1970 European tour and were booked as the opening act for the Jackson 5. Since then the Commodores have become top box-office, easily packing 20,000-seat sports arenas. In June they kick off a 100-date, five-month U.S. tour, their most expensive and elaborate to date. But, King cautions, "our theatrics are just icing on the cake. Richie may rise out of a cloud of smoke playing a piano, but if he doesn't have songs like Sail On and Easy to sing, then it's nothing.

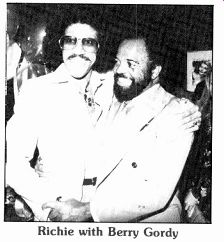

The music is the bottom line." In 1972, Ashburn signed the Commodores to Berry Gordy's Motown label, refusing to accept any advance for the group-an unusual move. "We wanted to get off on the right foot," explains McClary. It took two years before they re leased their first album because, he continues, "we didn't want to go the traditional Motown route." The label was accustomed to cutting instrumental tracks and then letting groups go in and sing on top of them. "We didn't want to do that," says McClary. "We wanted to play our own tracks. Motown said, 'Play your own tracks!?'-like we were nuts." "We were self-contained," adds LaPread, "and that didn't jive with Motown's assembly-line system." Finally, after running the gamut of in-house producers, they met Carmichael.

"Stumbled upon him," King jests. They re corded two singles, Machine Gun and The Bump, both written by Williams. Though the former was a disco smash, it failed to carry the Commodores' name along with it, probably because it was an instrumental. But the hits that followed did: Young Girls Are My Weakness, Brick House, Three Times a Lady, Zoom, Fancy Dancer, Slippery When Wet, Easy, Still, Sail On, and Wonderland.

This accumulation of platinum has made the Commodores a multimillion-dollar enterprise. Commodore Entertain ment Corporation with its two subsidiaries-Commodore Moving On Transportation (their touring operation) and Commodore Entertainment Publishing has grossed some $250 million in sales from albums, publishing royalties, merchandising, concerts, product endorsements (Schlitz beer among them), films, TV specials, etc. Considering their busi ness backgrounds, it's not surprising that they spend as much time thinking about the business side of things as the creative.

Fortune magazine phraseology--"built-in marketing strategy," "high-yield profit ratio"--abounds in their conversation.

Twice annually they hold official business meetings to discuss sales projections and budgets, bookings, and long-range plans.

(Film projects and solo albums are imminent for the '80s.) Says Richie: "I think of these guys more as businessmen than musicians. We try to keep costs to a minimum. We're always thinking of the bot tom line." Good business sense is one reason they've lasted so long; impartiality is another. Their publishing company, for in stance, is set up so that no one Commodore gets left out in the financial cold. "We have this system called the Where Fair Program," says McClary. "It allows for a rotation of guys sharing the B-side of a single. So everyone has had songs out in the street and on the charts." The group also has a long-standing policy of fining band members when they break the Commodores' disciplinary code, one that for Richie with Berry Gordy bids any drugs and restricts drinking on tour. Their image--"straight, clean-cut, and all-American"--is carefully maintained.

The group is musically ambitious, but they're also acutely aware of the marketplace. For instance, though they listen to a good deal of reggae, they've yet to incorporate any of its elements into their own music. "I don't think the masses are ready for it yet," says Richie. "Maybe in another album or two we might play some reggae." Carmichael also helps maintain a consistent market profile by keeping their sound within a certain stylistic framework.

"He strikes a real balance with us," Richie explains, "because he has a very conservative attitude toward recording, and, of course, we have no attitude at all. We're out there in left field, believe me." Watching the Commodores go through rigorous nights of arranging, rehearsing, and finally recording a song like Wake Up Children easily belies that off hand jest. So does the fact that, in a highly volatile industry, they've maintained the same personnel, staff, manager, producer, engineers, and record company throughout their last highly successful decade. The six still reside in relatively modest homes in and around Tuskegee Richie, Orange, King, and Williams with their wives and children. LaPread is a widower; McClary is the sole bachelor.

One gets the feeling that, naturally, the Commodores are success-oriented, but they're motivated less by a lust for cash than by a healthy sense of competition. Their oft-quoted goal is to be "bigger than the Beatles." Whether they'll achieve that is doubtful. What isn't so doubtful is that having shaken off the r&b stereotype they are a super-group to be reckoned with.

Studio Circuit--Back in the Home Studio:

The $2,000 Difference

by Bennett Evans

In the February issue we described how a to build a one-room studio for $2,000.

Not the biggest studio, nor the ideal studio, but one that would enable you to make clean, even moderately elaborate demo tapes and perhaps to earn a little money.

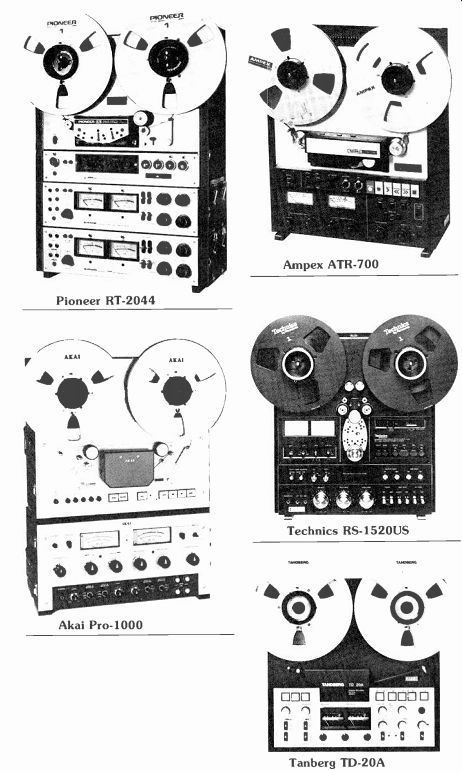

In this installment we'll move into slightly greener pastures-$2,000 greener, to be exact. How you spend your money depends, of course, on where you're starting from. If you followed our advice last time, you already own a mixer, some mikes and stands, and perhaps a quarter-track, but probably a half-track, tape deck. If you're happy with the deck you have, and with the service you get on it, consider buying another of the same make. If you've been doing your own servicing you'll be able to use your hard-won expertise to keep the new deck running right.

THE DECK

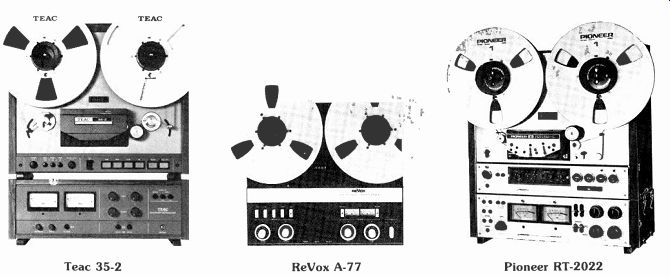

Our previous tape deck price range was $725 to $1,600. The sixteen decks listed on page 111

cost between $1,499 and $2,050, and with more money come more features. For easier editing, virtually all of them provide for cueing (listening) during fast-forward and rewind, and hand-rocking the reels to locate precise splicing points. Several also allow for "dump editing," i.e., winding off unwanted portions of the tape without the takeup reel whizzing around and damaging the end of the tape that you've decided to save.

-----If you missed the first article ("A Home Studio for $2,000? It Can Be Done!) in this series, send a self-addressed stamped envelope to Backbeat In formation Services, High Fidelity, 825 Seventh Avenue, New York, N.Y. 10019.

The Akai Pro-1000, Ampex ATR 700, and Tandberg TD-20A (all two-channel decks) have mixing facilities for up to four line inputs, which makes mixing down from a quarter-track simpler. Also, the Ampex and Akai have four mike inputs, which can be invaluable if you don't own a mixer or if you frequently do simple re motes and don't want to lug your mixer along. Those inputs (and those of the Otari MX-5050-2SH and Technics RS-1520) accept balanced lines, allowing longer mike-cable runs without noise pickup. Several decks have standard or optional balanced inputs and outputs for line-level signals, even where they don't have balanced mike connections.

Some of the more expensive decks have no mike inputs at all. These are de signed for a typical pro studio environment, where all microphones are connected to the mixer or console. Because these machines provide easier access to the bias and recording-EQ controls, you can adjust them to the specific requirements of different types of recording tapes. Some also have switch-selectable NAB (National Association of Broad casters) equalization (for U.S. use) and CCIR/IEC equalization ( Europe), in case you exchange tapes with overseas studios.

Channels & tracks. Most small studios today are pop-oriented, which usually means they make multitrack recordings. The more tracks available, the better, but our budget restricts us to a four-track deck. You'll also need a two-channel machine for mixdown. The question is, should it have half- or quarter-track heads? Half-track (also called two-track) is the studio standard. If you send your tapes out to be disc-mastered, for ex ample, the cutting house will probably expect, and certainly prefer, half-track tapes.

The half-track format also provides about a 3-dB better signal-to-noise ratio than quarter-track. Of course, you can't economize on tape-by flipping it over and recording in the other direction-the way you can with quarter-track. (Having done that, by the way, don't forget that editing tracks going in one direction will wreak havoc on those going in the other.) Most of the decks listed are avail able in half- and quarter-track configurations. Many-like the Technics RS 1500US-have additional heads, so that the half-track deck can play quarter-track tapes, and vice versa. The RS-15000S also has interchangeable head assemblies for recording half- and quarter-track tapes. Both of the Pioneer machines carry that versatility one step further: Change the 2022's half-track head assembly for a four-track one, and you have a quarter-track, two-channel machine. Add a second record /play amplifier, and you have a four-channel one.

THE MIXER The main difference between a $2,000 and a $4,000 studio is the capability provided by a second deck. But that's not the only difference. By careful spending, you can get a little more of everything else: more mikes (again I recommend Dick Rosmini's piece in the April 1978 BACKBEAT), more stands, more mixer.

Note that I said more mixer, not more mixers. For the most part, one big mixer beats two little ones-unless they can be ganged or stacked together. Some of the mixers covered last time-the 6-in/2 out Sony MX-650 and 670, the Tapco 6201B, and the 6-in/4-out Teac 2A-are stackable. Tapco's expansion unit (8201REB, $975) isn't just a duplicate mixer; it adds eight more inputs to the 6201B's six, plus reverb and equalization.

Speaking of reverb and EQ, let's look at some of the other features you'll find in mixers costing between $700 and $1,500. (February's range was from $160 for the Heath Kit TM-1626 to $599 for the Tapco 6201B.) Virtually all of them are stereo boards, with just two output channels. You'll rarely be doing four-channel ...

===============

Chan- Pitch Frequency Mike Make & Model Price Tracks nets Speeds Heads Meters Sync Control S / N THD Response' Inputs'

(50-20k :r 1) Remarks: Built-in 4-input mixer; 1/2-track record & play plus 1/4-track play; separate transport and electronics; pan pots on two inputs; independent mixer output for use with other deck; external processor loop; front-panel bias adjust and metering; front-panel equalization adjust; edit cueing; dual-capstan drive; selectable peak/VU metering; cue in fast-wind; optional wireless remote.

Remarks: Space for optional 4th playback head; memory counter reads in minutes and seconds; manually-defeatable lifters for cueing; motion-sensing logic; remote control; switchable NAB or IEC equalization; VU meter range switchable (0,+3,+6); built-in 4-in, 2-out mixer; master gain control; provision for dump edit; 3-position bias and EQ switches; also available for 334 & 71/2. and for'/4-track.

Ferrograph $1,950 2 2 15,71/2,334 3 2VU no no

60 0.2% 30-17k ± 2 2u 7602AH (30-20k ± 2)

Remarks: Adjustable fast-wind speed: master gain control; inter-track transfer for sound-on-sound or echo; mute switch to cut output during fast-wind;

optional remote control and indicator units; bass and treble controls; optional Dolby ($400); motion-sensing logic; 1/4-track available.

Otari $1,695 2/4 2 15,71/2 4 2VU yes no 68w 1% 50-18k ± 2 2u MX-5050-2SH (50-22k ± 2) Remarks: Optional balanced mike inputs; optional remote control; dump edit provision; built-in splicing block; tape lifter defeat; front-panel bias adjust with test oscillator; adjustable recording EQ and reference levels; motion-sensing logic.

Otari MX-5050B $2,050 2 / 4 2 15, 7 1/2.3% 4 2VU yes ±7% 66 0.7% 25-20k ± 2 2u (30-22k ± 2)

Remarks: All features of 2SH, plus: increased headroom; DC servo capstan motor with pitch control in recording and reproduce; peak-reading LEDs on meters; switch-selectable for 7 1/2 and 334 ips; memory counter; switch-selectable NAB/IEC EQ; balanced input available for line only.

Pioneer RT-2022 $1,590

2 2 15,7'/2 3 2VU yes no 57 1% 40-20k-- 3 2 u (30-22k ±3)

Pioneer RT-2044 $2,010

4 4 15,71/2 3 4 VU yes no 55 1% as above 4 u

Remarks: Machines identical save for head assembly and second 2-channel record/ play amp on 4-channel version; RT-2022 convertible to RT-2044 for $420; switch-selectable fixed or variable bias; 2 EQ positions each for NAB and IEC; 1 kHz/10 kHz test oscillator with external output: locking cue control: optional remote: wide-range meters calibrated from-40 to +6 VU.

ReVox A-77 $1,399 2/4 2 7'/2,33A 3 2VU Opt. Opt. 66 3% 30-20k, + 2,-3 3 u

Remarks: 71/2/15 two-speed version available ($1,499) ($150) ($145) ReVox B-77 $1,499 2 2 15,7% 3 2VU Opt. Opt. 67 0.6% as above 2u ($100) ($125) (30-22k, + 2-3)

Remarks: Dolby optional (71-dB S/N, $300); LED peak indicators; optional remote; mike, line and "radio" (2.8 mV) inputs; built-in tape cutter/splicer; monitor select includes mono and reverse stereo: sound-on-sound: logic control; 1/4-track and other speed pairs available; cueing in fast-wind or pause modes; motion-sensing logic.

Tandberg TD-20A $1,750

2 2 15,71/2 3 2 pk yes no 69w 2% 20-25k 3 2 u (20-30k 3)

Remarks: Actilinear circuitry to increase headroom and provide metal-tape capability (metal tape not yet available);cue and edit; mike/line or line/line mixing; master gain control; bias adjust: meters read equalized recording signal; optional remote: motor (not solenoid) actuation; wireless remote avail.; mike, line and radio (DIN) inputs: 1/4-track and 334 ips versions avail.

Teac Tascam 35-2 $1,900

2/4 2 15,7% 4 2VU no ± 10% 63w 1% 40-18k 3 0 (40-22k 3)

Remarks: Optional DBX; front-panel bias and EQ adjust; LED peak indicators: cue and edit; dump edit; motion-sensing logic; optional remote.

Teac Tascam 40-4 $1,700

4 4 15,71/2 3 4 VU yes Opt. 63w 1% 40-15k ± 3 0 ($350) (40-18k ±3) Remarks: Optional DBX; LED peak indicators; cue and edit; optional variable-speed adaptor yields ± 20% speed adjust but eliminates 7 1/2 speed.

Technics $1,500 2/4 2 15,71/2,3% 4 2VU no ±6% 68w 2% 20-25k ± 3 2u RS-1500US (30-30k ±3)

Remarks: Isolated-loop drive; quartz-locked direct-drive motor; logic control; optional remote; can operate on 24 VDC: tape counter reads minutes and seconds; 3-position bias and EQ selectors; meter scale selector; timer-start: edit dial; interchangeable 4/2-track head assembly; built-in stroboscope; bias and EQ adjustments on bottom; cue and edit.

Technics RS-1520 $2,000

2/4 2 as above 4 2VU no ±6% 60 0.8% as above 2b

Remarks: Similar to 1500 but with balanced-line inputs: front-accessible bias/ EQ adjust: built-in test oscillator: tape dump.

Notes:

'Performance at 71/2 ips (15 ips in parentheses); w = weighted.

Since different manufacturers use different weighting and measurement systems, do not assume that figures are directly comparable. b = balanced input. u = unbalanced.

=================

....recording. Instead, you'll be doing multi track recordings on your four-channel ma chine, and mix-downs from multitrack to your two-channel unit. For that, you'll need a slew of microphone inputs, four line inputs, and two output channels. Most of the boards in this range fill the bill, with from six to twelve input channels, switchable to either line or mike.

Unlike the lower-priced mixers, many of these have balanced mike inputs.

(Any board designed for serious use should have low-impedance inputs, of course.) Nowadays, most input modules have sliding controls or faders, though some still use rotary pots. There are ad vantages to both: Faders give you a quick visual indication of what your settings are, and it's easier to move a bunch of them at once. Rotary pots save space on the control panel, and, in some cases, allow for more precise adjustments than the short fader paths found on many of these boards.

Some mixers in this range have equalization for each input, usually in the form of low-, mid-, and high-frequency tone controls. Equalizers with shelving characteristics tend to be more common in still higher-priced boards and have elaborate graphic equalizers or even parametrics.

Panning (electrically positioning a signal anywhere between channels) is probably more useful in mixing down from a multitrack than in a live stereo recording. In the latter, you can move your mikes or performers to place the sounds where you'll want them in the final stereo image. Once they're on separate tracks, though, panning is the only way to get them anywhere but far left, far right, or dead center. (Reverb can help a little too, if your reverb system blends channels.) The number of patch points-that is, points of access to the circuits-in creases as the price goes up, too. Studio mixers in the kilo-buck range usually have patch points at the input and output to every circuit stage. That lets you pull all kinds of tricks: ganging equalizers for extreme frequency tailoring, patching around circuit stages that go blooey in the

===========

Glossary of Tape Deck Features

Balanced lines, usually found in pro studio equipment, are heavyweight, two-conductor-plus-shield lines and 3-pin XLR connectors. The ground lead is separate from the two that carry the signal in order to reduce hum pickup.

Home gear uses conductor-plus shield-or unbalanced-lines, with the signal return fed through the grounded shield and terminated at the "cap" of the relatively flimsy pin ("RCA" or "phono") connectors. Home setups rarely require the long cable runs that studios do, so noise buildup is less critical.

CCIR/IEC is the standard equalization curve used in some foreign countries, as opposed to the NAB equalization curve used in the U.S.

Cue can mean different things to different companies, but it usually means that the tape lifters can be defeated so that the tape remains more or less in contact with the heads in fast modes.

This enables you to listen to tape "chatter" in such modes to find a specific section of the tape. Many decks automatically reduce output level during cueing to save wear and tear on tweeters and to avoid magnetizing the heads.

DBX is a noise-reduction system that uses complementary compression and expansion to reduce tape noise. Not all DBX systems are precisely compatible with each other; check before playing back tapes made on a different deck with DBX encoding.

Dolby B is another noise-reduction system and is more widely compatible than DBX. In a real pinch, Dolby-en coded tapes can be played on non-Dolby machines, by using tone controls or equalizers (to roll off the highs) to approximate Dolby-decoded response.

Dual capstans in a drive system usually means that there are capstans and pinch rollers both before and after the tape heads. This isolates the tape from outside drag or vibration and maintains optimum tape-to-head contact.

Dump edit enables you to wind un wanted portions of tape off ("dump") while listening for the start of the de sired portion. When dump edit is en gaged. the takeup motor automatically shuts off. To dump edit without this feature, you either must remove the takeup reel or manually hold it fixed throughout the process.

Equalized meters are recording-level meters that read the signal after, rather than before, the recording equalization circuits. Signals that might cause tape saturation because they've been boosted by these equalization circuits are more easily detected with such meters.

External processor loop allows the signal to be fed through an external equalizer, noise-reduction unit, reverb device, or other signal processor. It works exactly like the tape-monitor loops on most home preamps.

Four-track/four-channel: In studio use, "four-track" denotes a tape deck with four separate record /playback channels, each using a separate tape track. The term "four-channel" would seem useful to distinguish these decks from quarter-track stereo decks, whose tapes have four identical tracks, though only two can be recorded or played simultaneously. But since the four tracks of four-channel decks are more often used independently (for multitrack recording) than together (for quadriphonic use), the term four-track has stuck and is unavoidable studio parlance.

Isolated loop (closed loop) is a trans port system in which the tape is pressed against both sides of a single, very large capstan by pinch rollers and passes over the heads between its first and second contacts with the capstan.

As with the dual-capstan drive, this isolates the tape from outside influences where it passes over the heads. The difference is that both pinch rollers press the tape against a single capstan, rather than against two separate ones.

Memory rewind allows you to automatically rewind to a preselected spot on the tape, for easier location of the start of the last take.

NAB is the equalization curve used in the U.S. (See CCIR/IEC.) Peak indicators, usually flashing LEDs, are used in conjunction with average-level (VU) meters to warn the operator of signal transients that are strong enough to cause distortion, yet too fast for VU meters to respond to.

Peak meters display peak, rather than average, signal values. They're sometimes referred to as PPMs (Peak Program Meters).

Pitch control is a variable speed adjustment (usually ± 5% to ± 10%) useful for increasing or decreasing tape time or matching the pitch of instruments recorded at different times.

Quarter-track usually describes a format that records four tracks on a tape, with two tracks (1 and 3) re corded in one direction, and the other two (2 and 4) recorded in the other.

(See four-track.) Transport logic protects the tape from breaking or stretching by automatically stopping it briefly between fast wind or rewind and record or play back. Motion-sensing logic can make the stop even more brief since it senses when it's safe to begin play rather than waiting a fixed period of time.

Two-track is a tape format that records two tracks, each almost half the tape's width, with a small, unrecorded guard band between them. Also called half-track.

VU meters indicate average, rather than peak, recording levels. Though not all averaging meters meet the true VU standard (which rigidly defines the response to certain specified test signals), most are marked VU nonetheless.

.

=======================

... middle of a session (usually just when you've become familiar with which input pot controls which instrument), inserting external signal-processing devices, and so on. With enough patching, you can re configure your board as easily as you can stack piles of toy blocks-with the advan tage that everything goes back to normal the instant you pull out the patch cords.

The $700 to $1,500 boards usually provide several operator conveniences that can speed up a session considerably.

CUE SEND sends the signal from a given board input to a headphone circuit, so the performers can listen to, for example, the rhythm tracks while overdubbing. Some boards also have a CUE CHANNEL, which picks up any input channel whose fader is pulled all the way down. This enables the engineer to listen to it without feeding it into the mix; it can be used to check signal quality, to tell when a tape track is nearing the point where you want to mix it in, or even to cue up tapes and records that will be fed into the mix later. MONITOR ASSIGN MENT buttons control which signals are fed to control-room speakers, which to speakers in the studio, which to headphones in each location, and so on. TALKBACK systems let the operator talk to the musicians via a mike on the board. His comments or instructions can be fed to their head phones or, between takes, through the studio monitors. All of these features tend to be necessary only when the control room and studio are separate. But even if you're working in one room (and we assume you are), keep the possibility of a separate control room in mind while you're selecting your equipment.

As studios get larger, even common features like VU meters become more important. In a small setup, you can put your tape deck right behind your mixer and use its recording-level meters directly. But if you have two decks, or if you must peer over the board to see what the musicians in the next room are doing, you'll need a mixer with its own meters. In most studio control rooms, the tape decks are set up behind the operator.

ON THE UPGR ADE Regardless of whether or not you think you'll be upgrading your studio, believe me it pays to shop for equipment with expansion in mind. For instance, you'll want to get a board with provision for outboard signal-processing, such as echo. A few mixers have it built in, but you'll need an additional echo unit (or a reverb or delay unit) eventually, so make sure there's a place to patch it in. EFFECTS BUSSES (such as echo) can take their signals from before or after the input faders.

Most mixers use post-fader SEND, since effects then follow the rise and fall of the in put signal naturally. But some interesting, if unnatural, effects can be achieved by feeding the effects busses directly from the input, before the signal is attenuated by the fader, which some consoles also al low. You'll find submaster controls on a few boards in this price class, and quite a few at higher prices. These let you fade several inputs in and out at once-useful, for example, when you've assigned three mikes to the drummer or brass section.

Of course, there's a lot more to a studio than tape decks and mixing boards, even if they are the two largest hardware investments you'll make. There are out board equalizers and echo, reverb, and delay devices; compressors, limiters, and noise reduction; rhythm devices; vocoders and synthesizers; equipment racks (6I1 that stuff has to go somewhere); patch bays; fuzz boxes, Hangers, wah-wahs, etc.

Most of these are available at moderate prices-but the cost of fully stocking a studio with them adds up. In our next installment, we'll see how many of these extras, in addition to the basics, a $10,000 budget will buy.

Saving up to move from the $2,000 to the $4,000 level may take a while, and moving from $4,000 to $10,000 takes even longer. But the time's not wasted:

While you're working, you're learning. For the most important part of your studio isn't what's in your studio. It's what's in your head.

Report from Winter NAMM: Less Hype, More Substance

by Fred Miller

As the "me" decade closes and we em bark upon what promises to be a period of technological advancement be yond our wildest dreams, musical instrument and accessory manufacturers appear to be buckling down to no-frills, common-sense marketing and merchandising practices. The NAMM (National Association of Music Merchants) shows of the late '70s were loaded with Madison Avenue hype-buttons, bumper stickers, balloons, and buxom babes wearing costumes of every description. Fortunately little of that was in evidence at last January's convention in Anaheim, California.

(Perhaps NOW finally caught up with NAMM.) The emphasis this time seemed to be on the product, not the packaging.

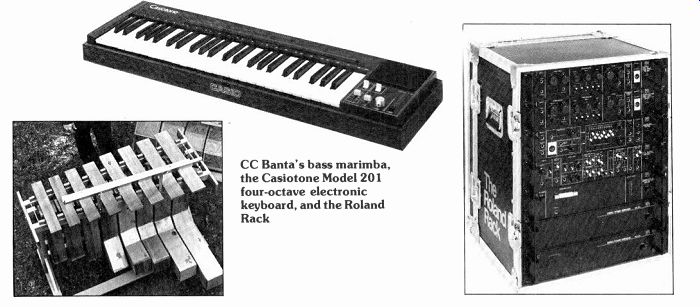

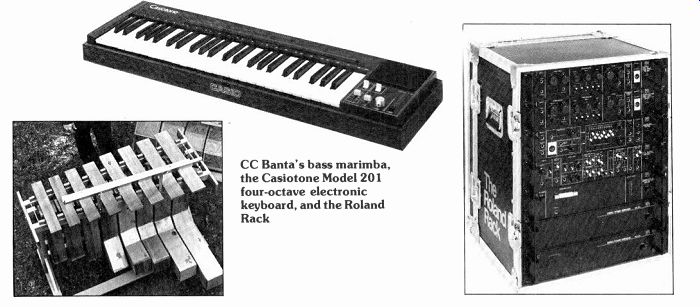

Among the new items on hand was a carrying case /drummer's rug combination from D'Aleo's of California. The rug provides a stable surface for setting up a drum kit and rolls up to hold up to eight heavy-duty stands in a shoulder-strap arrangement. Another innovative goodie, the Ploeger Sound Mirror, clips to the bell of a saxophone and reflects the sound back up to the player without interfering with what the audience hears. (No more playing into the wall to hear yourself!) And CC Banta displayed a bass marimba with huge wooden keys with tuneable resonators.

Casio, Inc., famous for their pocket calculators and musical timepieces, entered the musical instrument field with a series of good quality, low-cost electronic keyboards. Ranging in size from the 2 1/2-octave Casiotone 10 up to full-sized key boards, they are quite straightforward in operation and incorporate a wide range of instrument voices. Further down the aisle, Fender displayed its new bite-sized Rhodes Stage Piano with 54 keys. Fender is now making the tops of all its Rhodes (the 73- and 88-key as well) flat, at long last realizing that musicians occasionally need to be able to read music. This should also make it easier to stack the instruments. Con Brio introduced its ADS (Advanced Digital Synthesizer) 100, which comes complete with a programming panel, floppy discs (storage mediums for digital information), and a video screen. It reminded me of an elaborate version of RMI's keyboard computer. Moog's newest synthesizer entry is the Liberation, a port able, 3-octave monophonic unit that looks weird and sounds great. Speaking of look ing weird, Zephyr Manufacturing has de signed a truly wonderful mike stand that tilts toward the performer from its base and eliminates the need for goosenecks and booms. Another amazingly simple idea for my why-didn't-I-think-of-that file.

There were also many old favorites at the show, devices introduced over the past couple of years that have withstood the test of time. The Roland Rack, for ex ample, has become a very popular item, which isn't surprising since it's such a useful concept: an easily movable unit that incorporates such performance basics as preamp, power amp, flanger, delay line, compressor, etc. And electronic-drum manufacturers Synare and Syndrum are alive and well, refining a concept that just three years ago seemed downright revolutionary.

Although this was said to be the biggest NAMM Western Market show yet, it was clear that some belt-tightening has been going on in the industry. From where I sit, that's a healthy trend. I'm looking for ward to a decade that will be shorter on flash and pizzazz than the '70s were but longer on value and substance.

CC Banta's bass marimba, the Casiotone Model 201 four-octave

electronic keyboard, and the Roland Rack

Pop-Pourri---"Rock & Roll for a Desert Island"

by Stephen Holden

Anyone interested in rock and the literature that has grown up around it must read Stranded: Rock and Roll for a Desert Island (Alfred A. Knopf, $12.95), a collection of essays edited by Berkeley-based writer Greil Marcus, who received a National Book Award nomination several years ago for his Mystery Train. For Stranded he asked twenty rock critics-fifteen men and five women-to respond to the question, What one rock & roll album would you take to a desert island? Though the essays aren't all first-rate, together they present a powerful case for rock & roll as an art form and for rock criticism as a vital literary genre.

Nurtured in the pages of Craw-daddy, The Village Voice, and the mid-Six ties magazine Eye, rock criticism has developed into a uniquely open-ended personal, political, and cultural forum as stylistically diverse as the music it considers. Unlike his theater and film comrades, the rock critic doesn't have the power to make or break records commercially-radio does, principally. This makes him all but irrelevant in the marketplace, but at the same time it frees him of the temptations of publicity-mongering for his own "The real truth is that rock was invented by teenagers with pimples." benefit. Especially in the last five years, rock critics have used this freedom to take a longer literary/cultural view than the ater, movie, and even many book critics, and to develop intellectual and artistic stances sometimes as striking as those of the personalities they write about.

Stranded begins with Nick Tosches' riff on what the Rolling Stones have meant to him over the years. Gonzo jour nalism in the mode of Hunter Thompson, this funny, druggy reminiscence is a tour de force of intellectualized adolescent macho grossness. Equally iconoclastic is Ed Ward imagining the demise of the Five Royals, a fictional Fifties rhythm & blues group. This is the book's closer, and sand wiched between it and Tosches' joyride are a dozen or more pieces whose imaginative boldness and sheer zest outstrip most of what you're likely to find in a whole year's worth of The New York Re view of Books. In reassessing the Rolling Stones' late-Sixties masterpiece "Beggars Banquet," English critic Simon Frith makes a strong case for the album as "hilarious" and the Stones as "petit bourgeois jesters" and "poets of lonely leisure" whose rebellion has been "an aesthetic style without a core." Writing about Lou Reed and the Velvet Under ground, Ellen Willis celebrates the history of the aesthete-punk stance in rock & roll, then uses Reed's Street Hassle as the launching pad for a poetic leap of faith: "I believe that body and spirit are not really separate, though it often seems that way. I believe that redemption is never impossible and always equivocal. But I guess that I just don't know." Discussing the aesthete-punk dichotomy more hard-headedly, this time in relation to the New York Dolls, Village Voice critic Robert Christgau concludes, "Their music synthesizes folk art's communion and ingenuousness with the exploded forms, historical acuity, and obsessive self-consciousness of modernism." In these very well chosen words, Christgau comes closer than anyone has to defining the essence of post-countercultural rock.

Jay Cocks uses the career of Huey "Piano" Smith as the springboard for a vivid, stylish musicomythic history of New Or leans. Lester Bangs gets to the heart of Van Morrison's "Astral Weeks" by starting with a reminiscence of his own life at the time of its release (1968). He then literally enters the world of the album to the point where his language and Morrison's run together. The most compassionate and daredevil critic of all, Bangs ends his piece with dazzling side-by-side quotes from Morrison and poet Garcia Lorca. The book's funniest change of pace is from Bangs's piece to Dave Marsh's, which is a compilation of an imaginary album, "Onan's Greatest Hits," for the solitary man. "The real truth," writes Marsh, "is that rock was invented by teenagers with pimples, and acned adolescents are mostly getting it on with their fingers." Stranded's two best chapters-Tom Carson on the Ramones' "Rocket to Russia" and John Rockwell on Linda Ronstadt's "Living in the U.S.A."-couldn't be more dissimilar. Writing about the Ramones, Carson confirms Christgau's aesthetic, but with exciting rhetorical punches: ". . the appeal of twisting the whole hierarchy of success and defeat around to make it say the opposite of what it seems to mean. It's not graffiti transformed into art so much as it's art re deemed by the spirit of graffiti.... You could say that it's all a joke, done just for fun; but in America, simply having a good time is an elusive, tricky ideal, and even jokes have a moral significance . .. the kind of deadly serious kidding that rock 'n' roll, and America, couldn't live without." Rockwell's paean to Linda Ronstadt is the longest chapter and the only one to use standard musicological terminology. Though not many people will share the extent of Rockwell's adulation (he even prefers Ronstadt's version of Warren Zevon's Mohammed's Radio to Zevon's own), his essay, gathering together detailed musical analysis, various strands of rock history, biography, and personal reminiscence of his friendship with Ronstadt, is as comprehensive and passionately argued a piece of critical advocacy as I've ever read.

Editor Marcus, who in Mystery Train staked his claim to being rock criticism's archtraditionalist, caps Stranded with an "essential" discography that's as fascinating as it is partisan. Like all the best essays in the book, his list is informed with a brutal zeal for the authentic, combined with an equally brutal rejection of everything else. It is this zeal-adolescent insight and passion, focused, refined, and turned outward-that characterizes Stranded. Never mind that the use of intellectual dialect to exalt an anti-intellectual culture is, a fundamental, unresolved paradox; the writing is hot.

RECORDS

Zevon Strikes Again

by Crispin Cioe Zevon--a grisly presence in pop.

Warren Zevon: Bad Luck Streak in Dancing School Warren Zevon & Greg Ladanyi, producers.

Asylum 5E 509

A serious songwriter is one whose tunes have legs of their own. With Warren Zevon's third album (discounting a misguided and recently re-released disc from his very early days), both singer and songs now stand foursquare as substantial, if grisly, presences in pop music.

Though his talent and skewed sensibility were clearly established with his first two Asylum LPs, production weaknesses pre vented an equally strong musical identity:

The first, "Warren Zevon," lacked punch and sounded murky, while "Excitable Boy" had a slick veneer that obscured his rock & roll soul. From all available re ports, Zevon either couldn't or wouldn't take a strong artistic hand in those earlier projects. But "Bad Luck Streak," co-produced by engineer Greg Ladanyi, is his own album with his own musical footprints clearly audible on every song. Not surprisingly, those footprints are just as idiosyncratic as his gripping, often oblique tales from beyond.

These are songs of displacement, of people (and in one case of an animal) who are achingly uncomfortable in a hostile world. To match that, there's often a teeth-gritting, genuinely schizophrenic tension to the military rhythms Zevon uses. Sometimes he generalizes, as on the title track where the singer moans, "I'm down on my knees in pain, swear to God I'll change." The song is like a young boy's nightmare of violent discipline, set in some surrealistic "dancing school." Wild Age celebrates the classic American bad boy, a la James Dean, Marlon Brando, et al., with bittersweet backing harmonies from Eagles Glenn Frey and Don Henley.

Rick Marotta's muscular, crackling drums figure prominently in the mix on these songs, while David Lindley's weeping guitar solos add a touch of melancholy. Bed of Coals deals with the kind of morbid, self-pitying paranoia that is as American as country music. Fittingly, Ben Keith's funereal pedal steel guitar wafts through the song, as Zevon describes a "bed of coals, bed of nails," complaining that "I'm too old to die young, and too young to die now"-without, of course, ever identifying any specific ailment.

Ironically, as his stories become more specific, they become more universal, penetrating deeply into modern life and its discontents. Play It All Night Long paints an intensely grim portrait of southern life. While the band plays a dirgelike approximation of Lynyrd Skynyrd, the singer wails: "There ain't much to country living-sweat, piss, tears, and blood." Again, Lindley's atmospheric guitar poignantly underscores the chorus:

"Sweet Home Alabama, play that dead man's song, turn those speakers up full blast, play it all night long." On Jeannie Needs a Shooter, written with Bruce Springsteen, Joe Walsh's ringing guitar sets up a heavy-metal buckdance figure to accompany a western fable of star crossed lovers, and a supremely ironic punch line sabotages the song's initial Romeo and Juliet expectations. Only Ze von could write a straight ahead song about mercenary soldiers, and Jungle Work lays down the album's fiercest rock & roll. As the singer describes "battle in hell," a darkly ascending string section leads up to the chorus chant: "strength and muscle and jungle work." The verses could have been taken straight from the pages of Soldier of Fortune magazine, but the blood-curdling death screams on the fadeout are pure Zevon.

And yet, there's an idealist's moralistic edge to his celebrated flirtation with violence, as if he were as interested in purging evil as portraying it. Sometimes that romanticism emerges full-blown: Played on piano and harmonica alone, Bill Lee is a simple and earnest homage to the iconoclastic baseball pitcher, a man Zevon obviously admires for his outspokenness. Gorilla, You're a Desperado is a pure delight and one of his best com positions ever. Like Kafka's Metamorphosis in reverse, the song is about a "big gorilla at the L.A. zoo, [who] snatched the glasses right off my face, took the keys to my BMW, left me here to take his place." Unfortunately, the gorilla also assumes the singer's problems and ends up "very depressed, [he] went through transactional analysis." The album's sole cover tune is the Allen Toussaint (alias Naomi ' Neville) chestnut A Certain Girl, which the Yardbirds once popularized. The only truly lighthearted song here, it nonetheless fits Zevon's dour profile like a glove.

Three instrumentals, string quartets really, serve as introductions to as many songs. All are tasteful, recalling such composers as Samuel Barber and even Bela Bartok. Such eclectic programming works only because Zevon has literally turned his eccentricity into an integrated, discernible style. The album's one odd-tune-out is a very straight ballad, Empty-

Handed Heart, which talks about lost love in a "personal" way. When he sings, "Sometimes I wonder if I'll make it without you-I'm determined to," I think of Ross MacDonald, another Southern California writer who freely mixes the gruesome and the sentimental. "It isn't possible to brush people off," wrote MacDonald, "let alone yourself. They wait for you in time, which is also a closed circuit." Only romantics with their eyes wide open could write like this, and Warren Zevon's characters, including himself, know that circuit well.

The Brides of Funkenstein: Never Buy Texas from a Stranger George Clinton, William Collins,

& Ron Dunbar, producers Atlantic SD 19261 by Crispin Cioe Funk for George Clinton is like classical Indian music for Ravi Shankar or the blues for Otis Rush: a concrete musical form within which to develop a complete musical world view. Seen this way, all of

Clinton's productions (Parliament, Funkadelic, Parlet, etc.)

are more than just commercial outlets-they're variations on a recurring

theme. The Brides of Fun kenstein-Dawn Silva, Sheila Horn, and Jeanette

McGruder-also have been Funkadelic's lead female vocalists for years.

On "Never Buy Texas from a Stranger," Clinton casts them in the hard-edged funk landscape that is the Funkadelic trade mark (in contrast to Parliament's smoother pop surfaces). The Detroit in fluence that permeated that band's early-'70s songs, like Standing on the Verge of Gettin' It On, dominates here. Rocking guitars from Garry Shider, Mike Hampton, and Eddie Hazel slide between Bootsy Collins' bazooka-like bass and the Brides' multilayered vocals.

On Smoke Signals these threads weave a fabric of shifting densities that ranks with Clinton's best work to date.

The Brides chant phrases like "I'm sending up smoke signals, baby," in unusually voiced, angular harmonies, against which each singer steps out to solo and shout, space-age gospel style. In less capable hands, this might have come across as either chaotic or boring, but George has learned his formalist lessons well from the classic James Brown and Motown litanies.

(In fact, he was a Motown staff songwriter in the mid-'60s.) Even his serio-comic moralizing, like the follow-up to the title track line-"and never buy a bridge when you're in Brooklyn"-makes sense with the Brides wailing away over music this strong.

Burning Spear: Harder than the Best L. Lindo (Jack Ruby), Winston Rodney, & Karl Pitterson, producers Mango MLPS 9567 by Crispin Cioe In Jamaica and the world at large, Winston Rodney of Burning Spear (the other members are Delroy Hines and Rupert Willington) has been a charismatic reggae star for several years, equal to Bob Marley as a musical poet and seer.

"Harder than the Best" is a best-of collection, and, since his records pop up only sporadically in America, it serves as a solid introduction to his special gifts.

Where Marley and Toots Hibbert (of Toots & the Maytals) have drawn on American soul music for inspiration, Burning Spear is more African-based, and The Clash-fulfilling their much-acclaimed potential Rodney's ethereal voice is reminiscent of both Gold Coast traditional styles and modern singers like Hugh Masekela. His songs are often cinematic, conjuring up vivid scenes from a collective past: "Do you remember the days of slavery, when the work was so hard?. . ." Yet he uses gently rocking melodies, aiming more for education and enlightenment than rabble-rousing. (Rodney owns a general store/ social center in St. Ann's, Jamaica, and apparently leads the exemplary Rasta farian pastoral life.) Throw Down Your Arms, Social Living, and Black Wa Da Da are powerful and unique songs, the lyrics at once hypnotic and intellectual, the music's subtle Afro-Jamaican dimensions un derscoring the message. This is, as they say on the island, a top-ranking album.

The Clash: London Calling Guy Stevens, producer Epic E2 36328 (two discs) by Sam Sutherland Until now, the Clash has been lionized as much for its potential as for the quality of its recorded work. To a rock intelligentsia frustrated by the genre's commercialism and subsequent loss of urgency, the awkward angles and rough edges of the band's early singles and al bums were proof of its authenticity. The flaws of those records, such as haphazard production and sequencing (due in large part to ongoing squabbles with the record company), were elevated to the status of scars of uncompromised moralism.

The Ramones-a successful Phil Spector production

Yet this recklessly honest British quartet has been as limited as it has been liberated by the very passion so central to its critical esteem. It has been the galvanic live show that fleshed out the earnest rap port the band sought with its audience: on record, too often the narrow stylistic range and intensity of performance obscured the humor and humanism that emerged so vividly on stage.

"London Calling--transcends that paradox, achieving a quantum leap in the breadth and clarity of the Clash's music.

As such, it marks a triumphant turning point for the band, and possibly for the new rock movement with which it is associated. This is openhanded, openhearted rock modeled on classic sources and requiring little additional explanation be yond the songs themselves.

This time rockabilly, reggae, and various strains of r&b are displayed prominently against the guitar-dominated approach of the first two albums. Augmented by Micky Gallagher's keyboards and the brisk brass charts of the Irish Horns, those revisions as well as Guy Stevens' more lucid production finish amplify rather than obscure the songs' message.

The band's thematic concerns re main as provocative as before, based on the populist ideals it sees threatened by the repressive realities of Ireland, Jamaica, and its native England. If the Clash's targets are the same, its aim is more careful. "London Calling" thus achieves a stirring balance of psychological detail and moral force, similar to Elvis Costello's "Armed Forces" in its indict ment of Western decadence.

Such weighty themes still lead Joe Strummer and Mick Jones to chew their lyrics with angry relish, braying as much as singing them in rheumy, full-throated abandon. But the added shadings here more convincingly convey pathos, humor, and even joy-not just anger. As a result, the Clash's first double album is far more consistent and coherent than either of its single-disc predecessors. The thematic undercurrents begin on the apocalyptic title cut and continue through all eighteen songs in a richly colloquial voice that recalls both the raw rock energy and street-jive color of "Exile on Main Street." The Ramones: End of the Century Phil Spector, producer Sire SRK 6077 by Sam Sutherland The Ramones playing ballads? The Ramones using horns and strings? The Ramones turning down their amps and re sorting to lush washes of acoustic guitar? Has all reason fled? Is nothing sacred? That has been the initial reaction of several colleagues and Ramones admirers to the new album, but have no fear.

"End of the Century" does add such atypical twists to the breakneck kilowatt rock that has become the group's trademark, but the producer behind these new wide screen treatments is one of the few who can perform such major surgery without butchering the band's own perspective.

Phil Spector is himself a past master of teenage overstatement and exalted pop kitsch.

As a result, the corny string motif that accents the verses on a remake of the Ronettes' Baby, I Love You is more than matched by Joey Ramone's wonderfully maudlin lead vocal. Similarly, the flying wedge of wailing saxes that romps through the backdrop of Rock'n'Roll Radio is balanced against a fusillade of driving rhythm guitars. While Spector's pen chant for wall-to-wall orchestrations has swamped some of his more recent collaborations in bombast or melodrama, here the union proves felicitous.

Apart from letting several tracks retain the simpler attack of earlier Ramones records, Spector applies his more familiar techniques of sonic hyperbole to a willing subject: the gloriously unsophisticated protagonist that is the hero of every Ramones song. With the common goal of unabashed pop sentiment, rather than "artistic" pretense, "End of the Century" succeeds as a witty expansion of this prototypical punk band's exuberance.

Doug Sahm: Hell of a Spell Dan Healy. producer Takoma TAK 7075 by Sam Sutherland "Hell of a Spell" is the first Doug Sahm record in several years to find a home on a national record label. And it's both significant and heartening that his re turn to wider visibility comes under the aegis of the revitalized Takoma label.

Doug Sahm Sahm hasn't compromised the proud regionalism

that has always been his trade mark and that perhaps is the key to both

his vitality and his checkered commercial past.

Even his '60s rock efforts indicated his sense of Texas soul, tapping Tex-Mex roots and associated blues styles as much as rock & roll. Since then, "Sir Douglas" has turned his back on pop or rock hy brids to range through blues, country and western, and other local treasures as models for his own material.

As the liner explains, "Hell of a Spell" is devoted to "real S. A. blues . . .like the old days, back on the east side." That San Antonio musical dialect, which fleshes out classic blues forms with tight horn choruses and a fluid interplay be tween guitar and keyboards, is interrupted only once, on the title track. Here, Sahm's modified reggae points up the Jamaican genre's origins in the r&b records that were beamed to the Caribbean in the '50s and '60s from southern U. S. stations.

The songs and their alternately swinging and sultry performances all sound like authentic blues classics, but then Sahm has plied this style long enough to earn credentials as a blues art ist, not just a rock pretender flexing his sense of scholarship. The pop/ rock syn

================

Break Away---Bruce Woolley, Musical Frankenstein

by Steven X. Rea

------------

Bruce Woolley & the Camera Club Mike Hurst, producer Columbia NJC 36301 Bruce Woolley has seen the future of rock & roll and has embraced it with enthusiasm. The visual realization of that would be Bruce Woolley hugging himself.

The various musical trails blazed into the '80s by the likes of Elvis Costello, Devo, Brian Eno, and Talking Heads have met head on with the pure pop artistry of such hit-makers as the Electric Light Orchestra and 10cc in the '70s, and the Dave Clark Five in the '60s. Their collision is embodied in one young English singer/songwriter-a cynical, intelligent, yet still romantic tunesmith by the name of Woolley. He has glommed the avant garde precepts of the art-rockers, learned the misanthropy of the punk-rockers, acquired the frigid precision of the techno rockers, and borrowed the simple grace and melodic sway of the popsters. He is a musical Frankenstein, his debut LP a summoning of sundry parts into one devastating monster.

Woolley co-wrote Video Killed the Radio Star, a No. 1 hit in Britain and a charted single in the States as performed by a group called the Buggies. The Buggles' version-like their name-is cutesy teenybopper dross with a syncopated synthesizer sheen. On "Bruce Woolley & the Camera Club," Video Killed the Radio Star opens with the singer muttering the first verse in a vacuous whisper: "I heard you on the wireless back in '52, lying awake intently tuning in on you." then stately organ chords burst in and the song takes off. Woolley infuses passion where the Buggies employed mere gimmickry.

The result is that the song's theme of ma chine vs. man, technology vs. the individual, becomes clear.

Though futuristic, sci-fi trappings permeate much of his world, Woolley's main concerns are with human needs and desires. The LP's opener, English Garden, is a first-person account of impending senility or loss of sanity in the wake of stardom--all that's left for the protagonist are his flowers: "When the weather is right I do as a gentleman should, In my English garden." Here his vocals owe something to the distraught, twisted inflections of Talking Heads' David Byrne; the sense of reality-as-we-think-we-know-it slipping from the singer's grasp suggests Byrne's own paranoid world view.

Love and romance are dragged coolly in and ironically around the field in the form of jealousy (the melodically stunning Dancing with the Sporting Boys), rejection (No Surrender), manipulation (Johnny), adulation (You Got Class), and spiteful farewells (Goodbye to Yesterday).

Woolley is thus a pop craftsman in the classic sense, singing the classic theme love. But the framework of the songs is starkly modern.

The Camera Club is integral to all of this. Apart from sharing songwriter credits on several tracks, the quartet is adept at shifting rhythms, variably evoking taut, robot-like riffs, fluid, Eno-type electronic reveries (the instrumental W. W.9), hard rock, or smooth, lilting pop. Rod Johnson's drums are crisp and terse. Matthew Seligman's bass shores up and propels the whole works. Ex-Vibrator guitar ist David Birch keeps things to a palatable minimum but isn't afraid to let loose a shrill guitar line when one is called for.

The ultimate shaper of the Camera Club's sound, though, is keyboardist Tom Dolby.

The warm, regal tones of Bach, the sloppy effervescence of the Dave Clark Five in Flying Man (a totally blatant reworking of Glad All Over), and the mechanical rhythms in Clean/ Clean all appear mercurially at his command.

Bruce Woolley approaches his mu sic with restraint and a sharp, biting wit.

His lyrics are eloquent, sometimes surreal evocations of man in the modern world.

Amidst the slick, swelling harmonies of "Bruce Woolley & the Camera Club" there's a lot of wry humor. There's some thing to be taken seriously here too, and that is the very heartening indication of where pop music is heading in the '80s.

==============

.... thesist may argue that such vivid regional styles are on the wane, but Sahm is keeping them alive and well.

==========

JAZZ

Arthur Blythe: In the Tradition

Bob Thiele & Arthur Blythe, producers. Columbia JC 36300 by Don Heckman Arthur Blythe has apparently been bestowed Columbia's mantle of Resident Contemporary Jazz Alto Saxophonist.

Fine. He's a solid, interesting-if not terribly startling-player and deserves every shot he can get. But why toss him into the studio with an old-timer like Bob Thiele and ask him to play standards? Sure, Ellington's Caravan and In a Sentimental Mood, Waller's Jitterbug Waltz, and Coltrane's Naima are lovely pieces that de serve continuous examination. But shouldn't young recording artists first of all have a chance to speak their own words, to send their own messages, be fore we ask them to interpret the work of their illustrious forefathers? Blythe obviously loves and under stands Ellington, and, unlike one or two other young players who come to mind, he is generally comfortable with tough changes (especially in the bridge of Sentimental Mood and in the witty chromaticisms of Jitterbug Waltz). But, though he plays with verve and enthusiasm, he is generally upstaged by pianist Stanley Cowell. (Sometimes it is easier to be a sideman.) The fact is, Blythe has nothing particularly new to add to any of these standards and seems most at home on his two originals-Break Tune and Hip Dripper.

It's also worth noting that Columbia's production leaves a lot to be desired.

Steve McCall's drums and Fred Hopkins' bass sound fine, but Cowell's piano notes resonate like those of a cheap upright, and Blythe's alto sounds as though it was recorded inside a concrete sewer pipe.

John Faddis: Good and Plenty Vic Chirumbolo, producer Buddah BDS 5727 by Don Heckman What are we to make of this? At the age of eighteen, John Faddis was one of Blythe-the wrong fare the hottest young trumpet players on the New York jazz scene. I've heard him play brilliantly in every kind of setting, from big-band section work to small-group improvising. He has exceptional range, technique, and imagination.

But what he's playing here is trash.

Sure, Leon Pendarvis is a hot arranger; sure, he knows how to put an act on the Top 40 charts. But how sad it is that his particular brand of magic (sorcery?) has to be inflicted on a talent as fine and special as Faddis'. Yes, the big bucks potential of a production like this is a helluva lot better than that of a three-session, five-man jazz recording. And God knows, Faddis de serves the cash a lot more than some of the turkeys fluttering around the charts these days. But I wish there were a better way.

Anyhow, in case you can't repress your masochistic bent, "Good and Plenty" is disco-jazz, overproduced, overhyped, and cruel to the ears. So don't say I didn't warn you.

The Fabulous Bill Holman Reissue supervised by John Norris & Bill Smith Sackville 2013 by John S. Wilson Bill Holman's writing for big bands is focused on fundamentals. It is simple,

====================

--- Spin Offs

New Acts by Steven X. Rea D. L. Byron: This Day and Age Jimmy !ovine & Shelly Yakus, producers Arista AB 4258 "This Day and Age" doesn't let up, its taut, high powered rock charged along by pulsating guitars and drums. New Yorker D. L. Byron has his band, Protector 4, and producer Jimmy lovine to thank for the thundering, re lentless sound. Tracks such as Lorryanne, Love in Motion, and Get with It roar into high gear. Byron's songs and vocal phrasing are equal parts an them--like Springsteen and jerky Costello, with just a dash of the other Elvis on some of the late-'50s-tinged cuts (Listen to the Heartbeat). What grates here is Byron's affec tations; a good songwriter framed in a surging new waveish setting, he nonetheless owes too much to the afore mentioned artists to be taken seriously.

Richard Fagan Bob Gaudio, producer Mercury SRM 1-3811 Richard Fagan gained industry attention via his song-

writing credits on several Neil Diamond LPs. The surprise here is that instead of opting for Diamond's postured, soupy, dramatic approach, Fagan rocks straight ahead. He sings with a Dylanesque edge, while tracks like Don't Bother Coming Up, I'm Coming Down suggest the rough, frayed sound of Bob Seger.

Toto's David Hungate and sessioners such as keyboardist Jerry Corbetta flesh out a solid solo outing.

The Last:

L.A. Explosion John Harrison & the Last, producers Bomp BLP 4004 (2702 San Fernando Rd., Los Angeles, Ca. 90065) Sixties influences abound in this low-budget pro duction from L.A.'s independent Bomp label. The Last, an Angeleno quintet, runs the gamut from the Beatles to the Byrds, keeping it simple, short, and snappy. Arrangements are a touch lackluster, and the energy level a little low-a veteran producer would help spark things up a bit.

The Lonely Boys Andy Arthurs. producer Harvest ST 12030 Known as Little Bo Bitch in their native England, Lonely Boys is a more apt moniker for this lightweight fivesome. Pop/ rock is their game, irradiated by Dermot Moughan's keyboards, with just the slightest nod to the new wave here and there.

Lead singer Tony Watson's Cockney twang is the only ragged element in the band's catchy gloss. Weill/ Brecht in fluences appear on the bouncy The Lover. Not substantial stuff, but not awful either.

Ian McLagan: Troublemaker Geoff Workman, producer Mercury SRM 1-3786

Original Small Face and long-time keyboardist with the Rolling Stones/New Barbarians axis, Ian McLagan steps out on a jaunty, rollicking solo foray with help from Keith Richards, Ron Wood, Stanley Clarke, and Ringo Starr. Hz is an eloquently plainspoken song writer who comes straight to he point. His vocals are brash and spirited, making up in rowdy enthusiasm for what's lost in his limited range A couple of languid reggae numbers veer from the British rocker's true course, providing the only dull moments in this otherwise affable affair.

Off Broadway U.S.A.: On Tom Werman, producer Atlantic SD 19263 Off Broadway is an other mid-western quintet that travels Cheap Trick turf the Beatles, the Move, the Who, and, in this case, Badfinger.

Producer Tom Werman has framed this spirited aggregation in the same rich, textured setting that has marked his work with Cheap Trick. Lead singer/ songwriter Cliff John son does a wonderfully nasal McCartney, and his cohorts proffer bountiful harmonies.

This is pop with a capital P:

Hooks run rampant, and a punchy, gutsy rhythm section underpins the airy melodies.

"On" is a lot more consistent than Cheap Trick's "Dream Police." William Oz Stewart Levine, producer Capitol ST 12015 Substandard rock & roll here comes from a far too serious East Coast-based singer/ songwriter. William Oz evinces some flair for melody, but inane lyrics and stereotypical macho /rock posturing are a total turnoff. His band's adequate playing is supplemented by synthesizer wiz Larry Fast's dense electronic backdrop.

Denser still are the people who handed Oz a record contract.

Pearl Harbor

& the Explosions David Kahne, producer Warner Bros. BSK 3404 This Bay Area quartet fronted by singer/ songstress Pearl E. Gates landed a record deal after a homemade single, Drivin', started taking to the FM airwaves. Drivin' is the best cut here: booming, riffy rock that, well, drives. The three piece Explosions' strategy is to burrow into a rhythm hook and stay there; consequently, some of this debut LP is just dull. You Got It (Release It) is the other standout. Despite its image, there's nothing new wave about Pearl Harbor & the Explosions.

Sue Saad & the Next Richard Perry &James Lance, producers. Planet P4 This L.A. "new-wave" outfit has about as much to do with the new wave as their hair stylists. The tough, nasty (and screechy) stance by Sue Saad is propelled along by speedy guitars, bass, and drums. Reggae touches and some bluesy balladry on several songs ring a lot truer than the bam-bam bam rock. Not your standard Richard Perry production, by the way.

Robert Kraft-an original in a genre filled with poseurs

Continued from page 125 direct, and, when performed correctly, swinging. But because of its wide popularity, it has often fallen into the hands of groups that cannot project it properly.

"The Fabulous Bill Holman," originally re corded by Holman in 1957 for Coral records, should serve as an excellent model.

Not only has the Canadian-based Sackville reissued it in its original monaural sound and sequencing, but, more importantly, the relaxed performances provide an excellent showcase for Holman's work.

There is no heavy pushing, no shrieking brass, no great burst of excitement. Instead, a steady, pulsing momentum flows like a quiet but fascinating conversation. The virtually infallible rhythm section-Lou Levy on piano, Max Bennett on bass, Mel Lewis on drums-guarantees a swinging setting at any tempo. The soloists are also first-rate, most notably Ray Sims's mellow, slightly burry trombone with its occasional echoes of Bill Harris, Stu Williamson's steady, crisp trumpet, rollicking alto saxophonists Charlie Mariano and Herb Geller, and Holman himself on tenor.

Holman claims a wide variety of saxophone influences, from Tex Beneke to John Coltrane. The ones most evident here are Lester Young on the solos and Sonny Rollins, whose Airegin leads off the set. But on Come Rain or Come Shine, very little of either's style shows up. In stead, his warm and thoughtful development of the tune makes it almost a complete Holman showcase.

Robert Kraft and the Ivory Coast: Moodswing Phil Galdston. producer RSO RS 1-3070 by Crispin Cioe Everything that usually goes awry with modern vocal jazz worked out just fine on Robert Kraft's refreshingly auspicious debut album. Pianist/ singer Kraft emerged from the glitter-prone New York cabaret scene last year with an original pop/ jazz sound. His style is rooted in Mose Allison and Thelonius Monk, with light dollops of Latin and rock rhythms flavoring several tunes. This is the mother lode that Ben Sidran, Michael Franks, and, more idiosyncratically, Tom Waits have attempted to mine, with varying success. The danger in this, except for an original like Allison, is that it's easy to sound either mannered or slightly precious--i.e., if it's a pose, it shows.

Luckily, Kraft's persona as a latter day, jivey Cole Porter fits him as comfort ably as Waits's neo-beat posturings. On Junction Boulevard-which conjures up Manhattan street sounds with ingenious and purely musical textures-Kraft convincingly tosses off lines like "Handouts, then handshakes, the cons become the pros/ Each time a heart breaks some banker's belly grows." Conversely, his smoky voice is softly accurate, a la Mel Torme, on the diaphanously pretty ballad Bon Voyage.

Much credit for the overall success of "Moodswing" must go to Kraft's first rate band, the Ivory Coast. Eclectic violin ist Ross Levinson makes a brilliant debut with deeply emotional solos and rich duets with guitarist Stephen "T" Tarshis, all the while avoiding the usual fusion clichés. Bassist Ernie Provencher's tone and phrasing are superb. And producer Phil Galdston and engineer Elliot Scheiner (he of Steely Dan fame) have gotten marvelously resonant sounds from the players and their instruments, even on a couple of scat-swing numbers recorded live at Tramps nightclub in New York. In a tricky genre, these are all good signs for Kraft and his Ivory Coast.

Portrait of Marian McPartland Carl E. Jefferson, producer Concord Jazz CJ 101 by John S. Wilson With so many of Marian McPart land's recordings focused entirely on her piano, it is refreshing to hear her in a more varied and less consistently demanding context. On this disc, she is backed by drummerJake Hanna, bassist Brian Torff, and alto saxist / flutist Jerry Dodgion, who plays such a strong role that it is as much a "portrait" of him as it is of McPartland.

Dodgion shows his authority from the start with Herbie Hancock's Tell Me a Bedtime Story. His smooth, soaring at tack sets the piece floating in air and serves as a striking contrast to McPart land's running, low-register rumble. De spite his creamy tone on Tell Me, he avoids any comparisons with Johnny Hod ges until he gets to his own tune, No Trumps, on which he reflects Hodges' mixture of warmth and firmness. He enliv ens the slow, moving Spring Can Really Hang You Up the Most by delivering each note with precise, concentrated attention.

His flute playing is serviceable on Sara Cassey's lovely Wind Flower, and dashing and swirling on McPartland's Time and Time Again, particularly in some of the passages with Torff.

But McPartland does not take a secondary role. Her one unaccompanied number is a reflective, beautifully developed treatment of It Never Entered My Mind, which she approaches as a vocalist might. (One can almost hear Teddi King's phrasing.) She shares solos with Dodgion throughout, providing a dark and some times dissonant contrast to his soaring warmth. Hanna is an excellent, self-effacing drummer, coming to the fore only for a brief bit of brush work on I Won't Dance.

That tune also gives Torff a chance to show his disciplined facility as a soloist.

Jay McShann: Kansas City Hustle John Norris & Bill Smith, producers. Sackuille 3021 by John S. Wilson Though its title, "Kansas City Hustle," suggests busy, bustling traditionalism, this record should have been called "The Unexpected Jay McShann." As John Norris writes in his liner notes, McShann has been tabbed "just a blues player." His personal appearances usually do lean heavily on the blues, but they go far be yond the basic idiom, sometimes even revealing-as on this disc-sophistication with non-blues standards.

Playing with a light, clean touch in thoughtful, exploratory lines, McShann lends a fresh view to Round Midnight and Willow Weep for Me. Both have been played by jazz musicians of virtually every school, but he uses his blues as pastel coloring, adding a surprisingly sunny glow to the performances. Ivory Joe Hunter's (Since I Lost My Baby)! Almost Lost My Mind is gently blue; his own Blue Turbulence is not at all turbulent, but slow, re laxed, and very expressively blue. On this last he creates what amounts to a talking piano, the lines spoken with the rhythmic emphasis of a blues singer.