Massenet en Masse

As the boom grows, the remarkable versatility of a composer long known for a single opera becomes ever more apparent.

by Peter G. Davis

Two new recordings of Werther, the first really adequate Don Quichotte on disc, and Sapho, an opera never recorded be fore-the Massenet revival shows no sign of losing momentum. Philips has just taped the recent Covent Garden Werther with Frederica von Stade and Jose Carreras, while London's Sutherland /Bonynge performance of Le Roi de Lahore, awaiting re lease, will bring the total number of Masse net operas in SCHWANN to twelve. Who knows? From the remaining dozen works as yet unrecorded, we may one day hear Hero diade, Griselidis, Ariane, or Cherubin, all well worth reviving, at least for the phonograph.

Perhaps the most significant fact to emerge from the Massenet boom--and this latest batch of recordings only confirms it is the composer's extraordinary versatility, as evidenced by his sympathetic response to a wide range of subjects and his ability to individualize each opera. His seemingly endless fund of ingratiating melody, his sophisticated application of orchestral color to create atmosphere, and his elegant craftsmanship were never in doubt, even when Manon was the only work performed with any regularity a generation ago. But to say that "to have heard Manon is to have heard the whole of him," as Grove's would have it, is arrant nonsense.

------------------

MASSENET: Werther.

CAST:

Sophie Charlotte Katchen Werther Schmidt Albert Arleen Auger (s) Elena Obraztsova (ms) Gertrud von Ottenthal (ms) Placido Domingo (t) Alejandro Vazquez (t) Franz Grundheber (b) Wolfgang Vater (b) Lazio Anderko (b) Kurt Moll (bs) Children's Choir, Cologne Radio Symphony Orchestra, Riccardo Chailly, cond. [Rainer Brock and Michael Horvath, prod.]

DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON Christiane Barbaux (s) Tatiana Troyanos (ms) Lynda Richardson (ms) Alfredo Kraus (t) Philip Langridge (t) Matteo Manuguerra (b) Bruhlmann Michael Lewis (b) Johann Jean-Philippe Lafont (b) Le Bailli Jules Bastin (bs) Covent Garden Singers, London Philharmonic Orchestra, Michel Plasson, cond. [Eric Macleod, prod.] ANGEL SZCX 3894, $27.94 (three discs, automatic sequence). Tape: 4Z3X 3894, $27.94 (three cassettes).

CAST:

Sophie Charlotte Katchen Werther Schmidt Albert Bruhlmann Johann Le Bailli Cologne 2709 091, $29.94 (three discs, manual sequence). Tape: 3371 048, $29.94 (three cassettes).

MASSENET: Don Quichotte.

CAST:

Dulcinee Pedro Garcias Rodriguez Juan Regine Crespin (s) Michele Command (s) Annick Dutertre (s) Peyo Garazzi (t) Jean-Marie Fremeau (t)

Sancho Panza Gabriel Bacquier (b) Don Quichotte Nicholai Ghiaurov (bs) Chorus of the Radio Suisse Romande, Orchestre de la Suisse Romande, Kazimierz Kord, cond. [Christopher Raeburn, prod.] LONDON OSA 13134, $26.94 (three discs, automatic sequence).

MASSENET: Sapho.

CAST:

Fanny Legrand Renee Doria (s) Irene Elya Waisman (s) Divonne Gisele Ory (ms) Jean Gaussin La Borderie Caoudal Cesaire Le Patron Gines Sirera (t) Christian Baudean (t) Rene Gamboa (b) Adrien Legros (bs) Jean-Jacques Doumene (bs) Chorale Stephane Caillat, Orchestre Symphonique de la Garde Republicaine, Roger Boutry, cond. [Greco Casadesus, prod.] PETERS INTERNATIONAL PLE 129/31, $23.94 (three discs, automatic sequence).

---------------------------

In fact, Werther has now become Massenet's most popular work-every op era house in the world seemed to be staging the piece last season-and this domestic tragedy, with Werther's single-minded ob session mirrored in a score of remarkable economy and unity, is worlds removed from the delicately perfumed sensuality of Manon's seventeenth-century France. How artfully and subtly Massenet eases us into the cozy bourgeois home of the Bailiff-his "petit royaume," as he tells Werther-and the tragedy to come. The light opening scene, cast in a flowing melodic conversational style, leads into the hero's first appearance and the gradual intensification of mood that continues to mount throughout the op era as Werther's hopeless love for the married Charlotte becomes more and more desperate. In a sense, this is Massenet's most Wagnerian opera, with its interlocking web of leitmotifs used both to paint the psychology of the characters and to give the score a shapely unity of almost symphonic proportions. All this is done without depriving the voice of its primary function in the texture, and Massenet inflects the vocal line with special care to reflect precisely the interior passions of his two protagonists.

The title role has always been an irresistible lure for lyric tenors, and the pro fusion of such voices today no doubt ac counts for Werther's present popularity.

Actually, this has always been Massenet's most frequently recorded work-the two new versions bring the total number made over the years to eight, as opposed to four for Manon. The overall quality level in all the previous Werthers is also impressive, beginning with the first recording, made for Pathe in the 1930s, featuring the superbly stylish Charlotte and Werther of Ninon Vallin and Georges Thill. The only performance to survive in the domestic catalog is an Angel album (SCL 3736), starring Victoria de los Angeles and Nicolai Gedda, that has served admirably for the past dozen years.

A choice between the newcomers is relatively simple, for the new Angel recording scores over its DG rival in almost every respect. Much of the performance's distinction stems from Michel Plasson's conducting of the London Philharmonic. He shapes the music with a lapidary concern for orchestral detail, especially in the conversational bridge passages, where the interplay of solo winds becomes particularly ravishing. It is a leisurely performance, yet the music is never loved to death or allowed to drag. To the contrary, the love scenes pulsate vibrantly, the attacks are bitingly precise, the rhythmic pulse is always alive and forward-moving, the melodies are exquisitely savored and phrased.

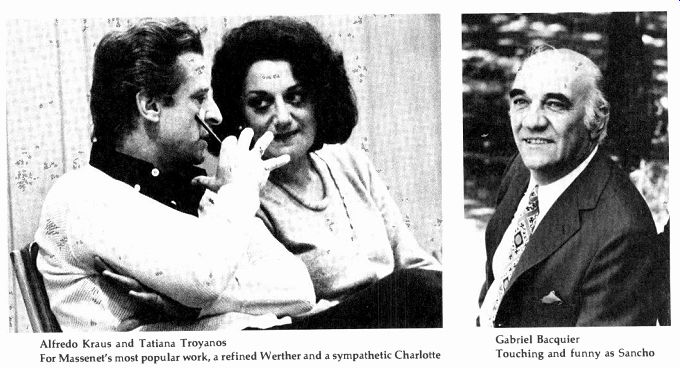

-------- Alfredo Kraus and Tatiana Troyanos For Massenet's most popular

work, a refined Werther and a sympathetic Charlotte; Gabriel Bacquier Touching

and funny as Sancho.

As in most French opera recordings these days, the cast is international, but Werther, more than most Massenet operas, has responded to foreign singers ever since its Viennese premiere in 1892. Here the Spanish tenor Alfredo Kraus re-creates his interpretation of the title role, one he has sung in almost every major operatic center.

Now in his fifties, Kraus has lost little vocal quality, and he sings with his customary taste, refinement, and care for integrating musical and dramatic values. His timbre may strike some as a bit too dry and his approach a trifle over-restrained, but his grasp of the style, the focused poise of his singing, and the dignity of his overall conception combine to make him today's preferred Werther.

Tatiana Troyanos' burnished mezzo-soprano is a gorgeous natural instrument, and she is a sympathetic Charlotte. While doing nothing especially out of the ordinary with the role, she still captures attention simply through the innate quality of her voice. Matteo Manuguerra makes a more positive figure out of Albert than most, while Christiane Barbaux as Sophie and Jules Bastin as the Bailiff leave little room for improvement. Angel's wide-ranging reproduction and luxuriously cushioned sonics suit the score perfectly.

DG's performance need not detain us long-here is a case where ecumenical musical forces fail to convince. The young Italian conductor Riccardo Chailly makes his recording debut with a brisk, sensible reading that has many solid virtues. He gets expressive, committed, and alert playing out of the Cologne Radio Orchestra, al though there is little of the felicitous attention to detail that distinguishes Plasson's conducting for Angel. Placido Domingo is in fine voice, and his extrovert Werther scores points for broad tenor abandon if not for delicacy or finesse. Elena Obraztsoya, on the other hand, is all wrong as Charlotte; her vibrato-laden mezzo, coarse phrasing, and weird French pronunciation turn the character into something quite repulsive. Arleen Auger's overly mature Sophie and the German singers in the cast sound distinctly out of their element.

Moving on to pleasanter things, Lon don's Don Quichotte can be warmly recommended as a more than serviceable performance of an instantly lovable opera.

Laid out in five compact acts, this treatment of Cervantes' novel depicts most of the familiar high points: the Don's wooing of Dulcinee, his battle with the windmills and confrontation with the bandits in an effort to retrieve his beloved lady's necklace, his gentle rejection by Dulcinee and lonely death with only the faithful Sancho Panza to mourn his passing.

This is late Massenet, composed in 1910 for the great Russian bass Feodor Chaliapin, and the composer's last unequivocal success. Perhaps he projected something of himself into the character of the aging Don Quichotte-certainly both men pined for beautiful young creatures and were destined to see their passions un requited. Massenet's affection for the Don is everywhere apparent, in the limpidly ac companied serenade to Dulcinee, his valor in the face of danger, his courtly dignity, the pathos of the death scene. The Don is the final great figure in the composer's gallery of singing/acting roles, a mellow portrait painted in delicate tints and with a depth of human perception unusual for Massenet.

Nor is Dulcinee neglected, a more complex figure than in Cervantes and a fun-loving, high-spirited girl capable of tenderness and passion. Sancho, too, is sharply delineated within a conventional but effective buffo tradition, and the colorful atmosphere of the Spanish setting is suggested by infectious dance rhythms and ornamental flicks, proving that Massenet's gift for piquant musical pastiche had lost none of its power to charm even at the end of his composing career.

If Nicolai Ghiaurov's interpretation of the title role does not overwhelm with any special insights, let alone efface memo ries of the recordings of Chaliapin or Vanni-Marcoux, the Bulgarian limns a sympathetic character, and for the most part, he sings splendidly. Regine Crespin may be a bit past the point where she can toss off Dulcinee's more florid passages with complete ease and security, but how consummately she can turn a lyrical phrase and find meaning in the simplest line of text-here is a great artist at work, vocal flaws and all. Gabriel Bacquier is his own capital self, portraying a humorous yet warmly touching Sancho Panza, and Kazimierz Kord conducts the Suisse Ro mande with panache and sensibility. London's plush engineering is very much to the point, although spreading this short opera over six sides seems rather uneconomical.

No matter. This is an infinitely superior ac count of the score as compared to the spotty, long-deleted Everest version from Belgrade.

Like Werther and Don Quichotte, Sapho is based on a novel, Alphonse Daudet's description of Bohemian artist life in Paris at the turn of the century. The plot ingredients are familiar enough: A slightly passee artist's model, Fanny Legrand, falls in love with an innocent young country swain named Jean, who is ignorant of her sordid past. When the facts eventually come out, there are quarrels and reconciliations until Fanny realizes that a shared life for people of such disparate backgrounds is impossible, and she leaves Jean for good. Echoes of Verdi's La Traviata and presentiments of Puccini's La Rondine are obvious in this oft-used material, but Massenet has a way of making it all sound fresh.

Sapho is unique in the Massenet canon in that it depicts contemporary society, a verismo type of opera very fashionable in 1897. (Charpentier's Louise, which came three years later, is the most notable example of the "musical novel" genre.) He makes a virtue of this and takes care to provide a musical background redo lent of the period. The brief opening act, for example, shows Fanny and Jean meeting at a party in the studio of the sculptor Caoudal, who had used Fanny as, among other things, a model for his statue of the Greek poetess Sapho. An on-stage gypsy salon orchestra sets the tone perfectly-its brittle, hectic, there's-no-tomorrow lilt sounds an ironic dramatic counterpoint to Jean's homesick reverie for the Provençal countryside and the future lovers' first glimpse of each other.

Massenet shows us every twist and turn in the affair, its delicate blossoming to idyllic bliss, raging fights, desperate at tempts to make up, and the final collapse of a tortured relationship. Each of these scenes is an object lesson in dramatic pacing and musical craft, shot through with a beguiling lyricism that never deserted the composer even when he was describing the most mundane activities of everyday life. Possibly one comes away feeling that Jean is something of a prig-and his simple, God fearing parents, Divonne and Cesaire, are a bit much-but Fanny's is a magnificent role, and a great singing actress can hardly fail to cause a sensation with it.

Unfortunately, the Peters recording fails in almost every department. The remnants of Renee Doria's voice can scarcely do justice to Fanny. Her intentions are sound, and she has the style well in hand, but her soprano is thin, pinched, and perilously unsteady. Gines Sirera has a service able tenor, typically French in its attractively buzzing nasal timbre, but he is musically crude and has an annoying habit of anticipating the beat. The rest of the cast barely passes muster, and Roger Boutty' conducts with a limp hand. Sapho deserves better than this, and with luck, the Masse net revival will provide something more worthy.

--------------

The "New Generation" of Mahler Conductors

by Abram Chipman

A wealth of releases proves that duplication need not mean redundancy.

By the mid-Seventies, Maurice Abravanel, Leonard Bernstein, Bernard Haitink, Rafael Kubelik, and Georg Solti had all recorded the canonical nine sym phonies of Mahler. By the mid-Eighties, these five-some of whom may offer re makes of their own-will probably be joined by at least as many others. Perhaps none of the current releases will form part of an "integral" edition in the most ambitious sense, including the completed Tenth and the "song symphony" Das Lied von der Erde, and in the strictest sense, featuring a single orchestra and a single label. Yet the recent windfall allows for a progress report on most of the probable contenders.

Andre Previn may appear to be an outsider in this company of Mahlerites. But Vaclav Neumann recorded the later instrumental symphonies in his Leipzig days most of the recordings are rare items these days-so the new Czech Philharmonic Fifth and Seventh (and an earlier Adagio from the Tenth) may well herald a cycle from Supraphon.

Zubin Mehta is definitely a candidate, though he has yet to garner strong endorsement from this corner. London has used both analog and digital techniques to record him with the Israel, Vienna, and Los Angeles Philharmonics. The new Third and the Lieder program with Marilyn Horne are fairly typical of the strengths and weaknesses of Mehta's Mahler.

DG is looking for a Mahlerite for the Eighties, and-to stretch the political analogy-has been conducting some suspenseful primaries in recent years. Seiji Ozawa seems to have bowed out of the race, as has Carlo Maria Giulini. While Claudio Abbado momentarily rests on impressive laurels with his Second and Fourth, Herbert von Karajan adds a Fourth to his variably received Fifth, Sixth, and Das Lied.

A powerful party supports Wyn Morris as a favorite son. His platform includes a stately, rounded lyrical style, consistent stereo separation of first and second violins, and advocacy of the five-movement Tenth (in Deryck Cooke's final realization) and the five-movement First (the only phonographic version of the 1893 edition).

These appeared on the Philips and Pye la bels with the New Philharmonia, though Morris' subsequent Mahler recordings have featured his handpicked Symphonica of London. RCA recently deleted the Eighth, while Peters' issue of the Second is now joined by the Ninth and a belated domestic issue of the Fifth.

As I read the polls, the front-running candidates are Klaus Tennstedt and James Levine. Clearly, Mahler's time has come, when a relatively obscure conductor can launch a major recording contract with a Mahler First, as Tennstedt did. EMI has promised a Tennstedt cycle with the Lon don Philharmonic and herewith offers the Fifth, with the now standard filler, the Adagio of the Tenth. Levine, one tires of saying, belies his youth with each fresh proof that he has absorbed the staggering complexities of Mahler's demands possibly better than anyone. His cycle, now roughly at midpoint, uses the broadest definition of the symphonies and includes the London and Chicago Symphonies, as well as the Philadelphia Orchestra.

So much for the rival candidates.

Now on to the music, starting with the vocal works and moving on to the symphonies, in order.

The songs Neumann adds to the Fifth satisfy no repertory needs, and bass Karel Berman shows no discernible sympathy for the idiom. He is out of his depth vocally in these oddly selected excerpts from two larger collections. "Revelge," from Des Knaben Wunderhorn, is cautious and reticent.

As for the Ruckert-Lieder, "Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder" suffers from Neumann's ill-de fined rhythm, while the other two offered here patently require the special poignancy of the mezzo timbre.

Which brings us to Home's Ruckert Lieder. Her rich, vibrant vocalism is fine in itself, but she pays insufficient attention to word meanings. Mehta, aided by a clear and powerful recording, revels in Mahler's spare but inspired scoring (e.g., the low winds and brass in "Um Mitternacht") and ...

--------------

MAHLER: Songs of a Wayfarer; Ruckert-Lieder (5). Marilyn Horne, mezzo-soprano; Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Zubin Mehta, cond. [Ray Minshull, prod.] LONDON OS 26578, $8.98.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 3, in D minor. Maureen Forrester, mezzo-soprano; California Boys' Choir, Los Angeles Master Chorale members, Los Angeles Philharmonic Orchestra, Zubin Mehta, cond. [Ray Minshull, prod.] LONDON CSA 2249, $17.96 (two discs, automatic sequence).

MAHLER: Symphony No. 4, in G. Elly Ameling, soprano; Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra, Andre Previn, cond. [Suvi Raj Grubb, prod.] ANGEL SZ 37576, $8.98. Edith Mathis, soprano; Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan, cond. [Hans Hirsch, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2531 205, $9.98. Tape: 3301 205, $9.98 (cassette).

MAHLER: Symphony No. 5, in C sharp minor; Symphony No. 10: Adagio. London Philharmonic Orchestra, Klaus Tennstedt, cond. [John Willan, prod.] ANGEL SZB 3883, $17.96 (two discs, automatic sequence).

MAHLER: Symphony No. 5, in C sharp minor; Songs of a Wayfarer. Roland Hermann, baritone; Symphonica of London, Wyn Morris, cond. [Isabella Wallich, prod.] PETERS INTERNATIONAL PLE 100/1, $15.96 (two discs, manual sequence).

MAHLER: Symphony No. 5, in C sharp minor; Songs (4). Karel Berman, bass*; Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, Vaclav Neumann, cond. [ Milan Slavicky, prod.] SUPRAPHON 4 10 2511/2, $17.96 (two SQ-encoded discs, manual sequence). Songs: Revelge; Blicke mir nicht in die Lieder; Ich bin der Welt abhanden gekommen; Um Mitternacht.

MAHLER: Symphony No. 7, in E minor. Czech Philharmonic Orchestra, VA clay Neumann, cond. [ Milan Slavicky, prod.] SUPRAPHON 4 10 2721/2, $17.96 (two SQ-encoded discs, manual sequence).

MAHLER: Symphony No. 9, in D. Symphonica of London, Wyn Morris, cond. [Isabella Wallich, prod.] PETERS INTERNATIONAL PLE 116/7, $15.96 (two discs, automatic sequence). Philadelphia Orchestra, James Le vine, cond. [Jay David Saks, prod.] RCA RED SEAL ARL 2-3461, $17.96 (two discs, automatic sequence). Tape: ARK 2-3461, $17.96 (two cassettes).

----------

----------- Wyn Morris: A stately, lyrical style; Vaclav Neumann: Few insights

... whips up a swaggering insolence in "Blicke mir nicht." Moreover, the sequence chosen for the songs is the most convincing I have yet encountered on discs. (Since this isn't a cycle, anything goes, presumably.) But in the intense privacy of these songs, the theatrical extroversion of Home and Mehta is a deficit; for more profound involvement, I turn to Christa Ludwig and Karajan (DG 2707 082) or Janet Baker and John Barbirolli (Angel S 36796).

On the other hand, the exuberant rhetoric of Home and Mehta well suits the overside Songs of a Wayfarer-that product of Mahler's youthful passion. What a contrast to the broadly spaced, static, and reflective rendition by Roland Hermann and Morris! As in the Ruckert-Lieder, preference in these songs is tied to the sex of the singer.

Women have essayed them many times on disc, of course, perhaps Ludwig most art fully (Seraphim S 60026). But I have long felt that these songs of a man's heartbreak ultimately call for a baritone voice. Thus, Hermann is at an obvious advantage, even though he never achieves quite the aching resignation of Heinrich Schlusnus (an elderly mono DG). Morris' conducting here is clearly modeled on Wilhelm Furtwangler's massive reading for Dietrich Fischer Dieskau's EMI mono studio recording (Seraphim 60272). But, as I have argued elsewhere, imitating Furtwangler is risky business, for the earlier Fischer-Dieskau/ Furtwangler Wayfarer, from a live Salzburg performance (Cetra LO 510), is far more volatile. The Fischer-Dieskau /Kubelik Wayfarer (DG 2530 630) still surpasses all corners in variety of text projection, management of the score's shifting pulses, and lucidity of orchestral textures.

Mehta could hardly care very deeply about Mahler's music and be so indifferent to the strictures of tempo the composer placed throughout the Third Symphony to keep its immense contours in balance. In the opening movement the conductor is warned not to hurry in such treacherous places as the introduction to the carnival-like outburst at Universal score cue 43 and the later reappearance of the opening horn call, but Mehta's enthusiasm whips him into a rushing frenzy at both points. And why the unctuous Luftpause before No. 73 in that movement's coda? At the sym phony's opposite end, the final Adagio, Mahler uses the initial, very slow, "restful and expressively singing" instruction as a primary pulse to which the music returns after numerous departures. In failing to consistently return to this (as James Levine does so impressively), Mehta deprives us of the sense of rootedness and destination through this unwieldy section. The ending of the second movement should likewise be carefully balanced between holding back and moving steadily, another distinction over which this interpretation rides rough shod. At least the scherzo has more pep than usual.

Mehta's control of the orchestra is little better than his slapdash self-control.

The Angelenos play competently, but that isn't enough (at least on a record that one will presumably live with for a time) for a symphony scored with such shimmering nuance and dazzling pyrotechnics. An overly loud pianissimo here, some tonal crudeness there, slightly sour woodwind intonation in this place, and scraping strings in that-the effect accumulates, be coming more than the sum of its parts. Ensemble verges on confusion from time to time (e.g., between cues 12 and 13 of the second movement), and the trumpets fail to sound over the whole orchestra in the concluding pages. Maureen Forrester is ruthlessly over-miked in her solo movement, her ...

--------- Herbert von Karajan: More commitment to Mahler

... every sign of strain painfully exposed. (Her voice was in better estate in the Haitink recording.) The only minor compensations for all this are a good, clearly recorded fifth (choral) movement and the use of what could well be a real posthorn in the scherzo.

In short, Mehta is a woefully inadequate guide through the wondrous universe of Mahler's Third. The breathtaking beauty of the work is slighted by all concerned, and the conductor's self-indulgence-elsewhere hyped as some sort of romantic identification with the soul of Mahler-amounts to incomprehension, if not downright disrespect. For the rest of its Mahler recordings with Mehta, I hope Lon don will stay away from Los Angeles and Israel and stick with the Vienna Philharmonic, which at least can play the music and exert some taming influence on the conductor.

Meanwhile, if you need a Third, take your pick of Haitink (Philips 802 711/2), Horenstein (Nonesuch HB 73023), Bern stein (Columbia M2S 675), or Levine (RCA ARL 2-1757; reviewed with extensive comparisons of the other three, March 1977).

At an earlier stage of Mahler performance, Previn's Fourth would have been perfectly acceptable. It is reasonably straightforward, taut, and dependably well played. But by the standards we take for granted today, it lacks meltingly beautiful violin tone, piercingly brilliant oboe and trumpet work, and range and power of re corded sound (e.g., the dampened climax at cue 11 in the Adagio). The many moods of the finale are weakly characterized by Previn's rigidly unsmiling approach, and, as with Forrester in the Mehta Third, Elly Ameling's vocal wear is mercilessly ex posed by the miking; she, too, was heard to better advantage in a Haitink version of the Sixties (Philips 802 888).

Karajan, with each successive outing, seems to be turning into a real Mahler conductor. Granted, this Fourth shares some minor shortcomings with Previn's: in consistent observance of string glissandos (sometimes omitted when marked, some times played when unmarked); failure to accelerate in the middle of the horn solo near the end of the first movement (thus minimizing the allusion to Beethoven's G major Piano Concerto); clarinets that are too timid in the grotesque "resounding" outburst near cue 4 in the scherzo. But what deeply committed playing by the Berliners! Horns are magnificent and powerful; strings glow passionately; rubato is instinctively felt. Edith Mathis provides ample tonal range, secure pitch, and a warm and fanciful shading of the text. DG's recording is beautifully detailed and focused, with spacious, heaven-storming climaxes in the slow movement.

There are two puzzling peculiarities, however: At both cues 21 and 22 in the opening movement, Karajan ignores the caesuras, shifting seamlessly into the new tempo before the string sound has died.

(Perhaps he is overreacting to the exaggeration of this discontinuity by many other conductors.) And near the end of the Adagio, I don't hear the final mf timpani strokes over the pizzicato double basses.

Nevertheless, Karajan's takes its place among the very finest recorded performances of this music, fully the equal of the Von Stade/ Abbado version (DG 2530 966, January 1979). My preference for that earlier edition is purely subjective: Abbado seems to re-create the piece afresh with un blushing, childlike wonderment. Karajan's is basically a sophisticated adult view.

------------73 Klaus Tennstedt Immersion in Mahler's language;

James Levine The best Ninth yet?

------- Andre Previn Straightforward but rigid.

Mahler's Fifth is heavy going in its formidable challenges to a conductor's powers of observation, concentration, and organization. Levine (RCA ARL 2-2905, February 1979) has negotiated those demands most successfully of anyone on disc.

None of the three versions at hand adheres completely to the 1964 Critical Edition, which, for example, excludes percussion around cue 17 of the first movement (as does Levine). Neumann and Morris include timpani parts, and I faintly detect a snare drum from Tennstedt.

Neumann's older Gewandhaus Fifth (Vanguard C 10011/2), though never one of my favorites, was more vigorous than the remake in the scherzo and much of the finale. Predictably, the Czech Philharmonic plays better than the Leipzig aggregation.

The opening trumpet solo, for instance, carefully heeds the dynamic markings, so the funeral procession seems to be moving toward the listener. Supraphon's sound surpasses Vanguard's primarily in wood wind clarity. But alas, Neumann offers few insights to compensate for his two disastrous miscalculations: When the funeral music recurs in the second movement with a return to original tempo indicated, he is absurdly fast; and in the finale, he jams on the brakes at cue 32, when he should maintain stride and build up to the work's real climax at the slightly later recurrence of the triumphal tune. As in his earlier version, there is an unwanted break between the Adagietto and the finale.

Morris' Fifth is longer than any I know of; this grandly valedictory, warmly flowing interpretation should appeal to admirers of the similarly expansive but more thickly textured Barbirolli (Angel, deleted).

Also praiseworthy is the solid, enveloping richness of the Peters pressing, with quieter surfaces than the Supraphon and Angel review copies. There are controversial touches in the reading: At both the pat mosso subito in the second movement (following 73 cue 16) and the motto moderato in the scherzo (following cue 14), Morris' tempos are so slow and sedate as to approach parody. Yet there is a rapidly flowing and detailed Adagietto to balance the prevalent solemnity. The orchestral playing is fair.

Tennstedt's Fifth (unlike his earlier First) evokes a sense of deja entendu at re-encountering the Bruno Walter style of Mahler conducting so many of us grew up with.

(Walter's classic Fifth is still available on Odyssey 32 26 0016, rechanneled.) If not deliberately slighted, virtuosity, textual exactitude, and linear transparency seem not so much obsessive ends in themselves as means to, or incidental by-products of, a native immersion in the singing, breathing, pulsating language of Mahler's cultural roots. The result is a performance of organic integrity and spirituality. Note the palpable "give" of the second pulse of the first movement ("etwas gehaltener"), so Walter-like in its cradling, consoling lilt; the starkly desolate shudder at the "klagende" climax of that movement; the bucolic gaiety of the winds' ornamental turns in the finale.

The Adagietto flows lightly, never overbearingly, with utterly melting cello tone.

Walter again comes to mind in the scherzo, with its completely natural feel for rubato and the bittersweet regretfulness of the string playing.

Yes, Tennstedt does anticipate ritards prematurely throughout the scherzo, and he creates a dizzy stretto in its final pages. Purists will also question the rhythmic liberty of the work's opening trumpet call. But these objections ultimately pall, for this is an interpretation of deep beauty and cultivation, even though somewhat flawed in realization. At times, either ensemble or recording balance is slightly askew. Moreover, the loudest climaxes tend to overload, the bass drum's whispers at the end of the first movement are scarcely audible, and Tennstedt's conscientious attacca into the finale is compromised (like Morris') by pre-echo.

In recent years, the Seventh (Song of the Night) has begun to seem like a Cinderella among Mahler's symphonies. The current SCHWANN lists only the original cyclists (and not all of those). It is a tough nut to crack, because its scoring is thicker (less "chamber-music-like") than that of its companions and because it can verge on banality unless the conductor fully enters its eerie world of half-lights, spooks, and things that go bump in the night. Without that almost hallucinatory kinship, mere musicianship and brilliant playing can go for naught. With it, one can get away with less than perfect execution (e.g., the raw-edged intensity of Abravanel's still powerful stereo premiere with the Utah Sym phony on Vanguard 71141/2) and even with outrageous eccentricity (e.g., the in sanely absorbing and revelatory Otto Klemperer account recently deleted by Angel).

For all of these reasons, the new re lease is difficult to recommend. Neumann has a spectacular orchestra in the Czech Philharmonic, very nearly as responsive, on-target, and characterful as Haitink's Concertgebouw (Philips 6700 036). Supraphon has obliged with a recording of somewhat greater vividness than its Fifth.

Neumann directs the flow of instrumental traffic with alertness and precision. (I have never heard, incidentally, his earlier Seventh with the Gewandhaus on German Eterna.) But I miss everywhere a cutting edge of rhythmic tension, of springy articulation, of tautness in attacks and in hairpin dynamics. And there is too little rapt and mysterious soft playing. In the first movement, the buildup and release of the climactic tension should be positively teeth-grinding at the grandioso marking (cue 50) and again at the change from 3/2 to 4/4 after cue 65. Neumann understates the associated tempo changes. In the first Nachtmusik movement, the spectral march episode is so fast as to seem brightly and blandly cheerful, while the deadpan treatment of the seductive dance music suggests Neumann has never been to a Jewish wedding.

The second Nachtmusik movement (Andante amoroso) is taken like a corpulent Adagio, thus slighting its anxiously tentative, frail, ambivalent love song. In the finale, Neumann is more attuned to the heady swagger than to the complacent, mincing moments of burgher-like deliberation.

True, Bernstein's and Solti's renditions had some of these problems, but that does not lessen my disappointment in the symphony's first recording in a decade. Until the new cyclists swell the ranks, Haitink's remains the preferred version, with plenty of bite and urbanity, though it too could be more phantasmagorical.

------- Zubin Mehta Indifferent to Mahler?

Morris' and Levine's Ninths have only two points in common: They both opt for the slowest sustainable tempo in the final Adagio and for lateral division of first and second violins. The latter is no surprise from Morris, but is innovative from Levine.

I only wish he had seated his strings that way from the start. RCA's recording also deploys the brass unconventionally (and, to my mind, ideally): Horns across the rear are flanked by trumpets on the right, from bones and tubas on the left.

In addition to its optimal stereo effectiveness, Levine's surpasses almost every other Ninth in fidelity to the printed page.

Virtually every nuance of tempo, dynamics, articulation, and expression is scrupulously realized, right down to the closing pages, with their near-impossible demands for gradations of softness to the very threshold of inaudibility. The dazzling per mutations of choir blending are all meticulously balanced so that everything "sounds" with vivid cogency and daring.

The virtuosic Philadelphians take nothing for granted. In the middle movements particularly, each shrieking, wailing, flatulent, or maliciously snarling outburst from the winds and brass sounds as if the players were possessed.

One can argue, of course, that the whole of a performance is more than the sum of its parts, and there is much to a work like this that is written between the lines.

Jascha Horenstein's great-if frequently ragged--1966 performance with the Lon don Symphony (commercially unavailable) comes to mind, with its hesitant upbeats in the Landler and its ineffable weariness. But Levine's analytic scrutiny extracts most of the work's inherent eloquence and is absolutely compelling; this performance will not soon be duplicated.

Morris barely leaves off where Le vine begins. Warmth, gentleness, and sincere effort are all there. In the attempt to capture the lyrical sweep of the first movement, however, essential details of tempo are passed over. In the second movement, the third of the alternating dance pulses is far too hasty. In the ensuing Rondo-Burleske, the main tempo is much slower at its "return" after the central lyrical section (which is played too loudly). Execution is too often slipshod: Horns fail to manage trills and grace notes, the solo violin gets ahead of the winds, triplets are wrongly phrased, etc.

Our earlier political analogy is particularly apt in discussing the Tenth. One cyclist, Solti, holds fast to the conservative position, refusing to touch an unfinished work. The radical Morris holds that a conjectural completion of all five movements is a legitimate-nay, essential-part of Mahler's symphonic output. One conservative, Bernstein, has lately shifted to the centrist position that the opening Adagio alone is performable as legitimate Mahler. Most of the past and future cyclists take this stand, though Levine, a onetime centrist who re corded the Adagio alone, is now moving to the radical camp and intends to record the realization of Cooke, whose re-scorings he already accepted in the Adagio.

Tennstedt is one of the centrists, and, like most of his colleagues, he employs the Critical Edition of the Adagio, with none of Schalk's, Krenek's, or Zemlinsky's earlier additions to the manuscript or Cooke's later ones. Those wanting this movement alone will find fiercer attacks and weightier sonorities in the recordings of Bernstein (Columbia M 33532), Levine (RCA ARL 2-2905, with the Fifth), or Neumann (Quintessence 2700). By contrast, Tennstedt's reading is songful and lei surely, more a prelude than a climax. Except for some pre-echo before the dissonant fortissimo outburst, the sound is fine.

Some conclusions may be drawn. It is the prerogative of geniuses like Gustav Mahler to have their works looked at from so many vantage points, and competition for a nonexistent "chief executive" office serves to raise the general standards of performance and the range of our appreciation. The individual profiles of these conductors are beginning to emerge from the samplings described above. They are a varied lot indeed, and the one thing we need not fear from this abundance of duplication is artistic redundancy. HP

-----------------

(High Fidelity, Apr 1980)

Also see:

The Tape Deck, by R. D Darrell

Predictable Crises in Classical Music Recording, by Allan Kozinn