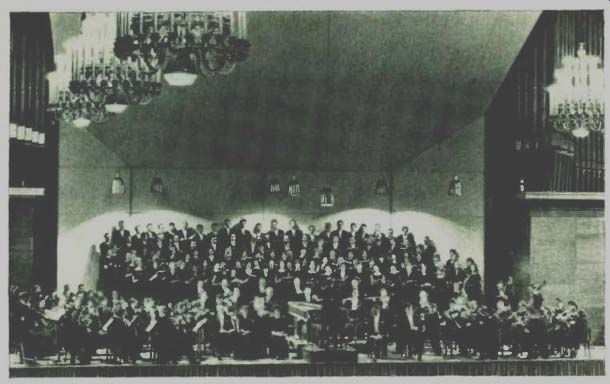

-------- Karl Richter with his youthful Bach Choir and the ever-changing

Bach Orchestra in Munich's Herkules-Saal.

MUNICH

For Beethoven's Birthday--The Mass in C from DGG

The flood of Beethoveniana on disc should reach stupefying proportions before December 16, 1970, the official 200th birth date. Deutsche Grammophon, in fact, has some especially spectacular plans afoot to mark the occasion, although Polydor, DGG's American distributor, is keeping the specifics under jealously guarded wraps until next fall.

One small omen of things to come is a new recording of the Mass in C and the rarely heard Elegiac Song, Op. 118: both works were taped last summer by Karl Richter and his Munich Bach Choir and Orchestra.

The site of the recording session was Munich's comfortably appointed Herkules-Saar-one of DGG's favorite auditoriums and used in the past for such projects as Rafael Kubelik's complete Mahler cycle, Schoenberg's Gurrelieder, and Richter's own Bach cantata series.

Although a thoroughly equipped studio on the balcony level is always ready and waiting for action, the hall itself requires a good deal of preparation before sessions can begin. When I arrived on the evening of August 7, the engineers had already set up a network of microphones, the rows of sound-absorbent felt seats had been covered with long sheets of plastic, and from the balcony a crew of Bavarian Television technicians were training their cameras on the proceedings as part of a special film describing the inner workings of a recording session.

To anyone meeting Richter's Bach Choir and Orchestra face to face for the first time, the most immediately striking aspect of the ensemble is its youth. The age of the chorus members ranges from sixteen to twenty-five-older singers are systematically "retired" by the conductor who likes to maintain the fresh, spontaneous sound of young voices, all of them either amateurs or students.

The orchestra is comprised of some of Germany's finest players, the strings drawn primarily from the Orchestra of the Bavarian Radio, the winds and brass often summoned from as far away as Detmold. Not at all a permanent ensemble, the Bach Orchestra is newly contracted for each concert, tour, and recording session-quite a challenge for Richter who must mold a homogeneous group afresh on each occasion. The session I attended began with the very Handelian Credo, and the full orchestra, chorus, and soloists (Gundula Janowitz, Julia Hamari, Horst R. Laubenthal, and Ernst Gerold Schramm) were assembled for a hard evening's work.

Richter's cool, crisp, slightly aloof podium deportment belies the characteristically crackling musical results he obtains from his forces. All of his instructions were delivered so clearly and articulately that it was rarely necessary to go over a passage once the essential musical problems were straightened out. When the music mounted in excitement, however, Richter couldn't resist throwing himself into the fray by jumping up from his chair to emphasize an accent or crescendo--once with a resulting stamp of the foot that marred an otherwise flawless take. These occasional bursts of temperament aside, Richter's work methods were a model of efficiency and he was usually able to anticipate problems before they even occurred. "Instead of a fermata, we'll take one measure rest here," he warned the players, who caught his meaning without missing a beat and the music continued uninterrupted. In order to ensure maximum coordination between chorus and orchestra, Richter hit on a unique device: "Sopranos, watch the first violins' bows--that's precisely how fast your eighth notes should be." It worked, and the rapid passage of simultaneous runs rolled out smoothly without a hint of raggedness.

The sonic perspective changed radically in the control room. Here, through two large speakers in opposite corners of the room, one could hear the balanced sound after it had passed through engineer Klaus Scheibe's mixing panel. Achieving a good blend with so complicated a work is a tricky job: chorus, orchestra, and soloists, each with their separate microphone pickups, must all be in perspective--the responsibility of the musical producer, Rainer Brock. Brock offered forthright suggestions to Richter via an intercom telephone, occasionally pointing out minor infelicities of ensemble and balance. During breaks in the session, Richter visited the control room to hear the complete takes and compare notes with DGG's team. After the evening's work was in the can, the engineering crew stayed behind for onthe-spot editing, and by midnight the master tape of the Credo was completed another link in DGG's proposed mammoth celebration of the Beethoven year. PETER G. DAVIS

PARIS

EMI'S New Spoken /Sung Carmen

July 1969. Armstrong, Aldrin, and Collins were on their way to the moon. The thermometer in France was mounting to record highs and the humidity was playing exasperating tricks with the pitch of the strings of the Paris Opéra Orchestra.

The orange polo shirt of conductor Rafael Frühbeck de Burgos was a vast blotch of perspiration. The bull ring of Seville, occupied by the chorus of the Paris Opéra, was located for stereophonic reasons on the ground floor of the Salle Wagram. Upstairs, on a blue and white checkered stage, Don José-Jon Vickers in brown slacks and a very warm-looking tan sweater-was pleading passionately "there is yet time" to a fatalistic, unyielding Carmen--Grace Bumbry, in a stunning white lace mini-skirted dress, white necklace, and white stockings.

Thus began the recording of the latest EMI complete version of Bizet's masterpiece. After a few days, work was halted and was not resumed until September.

At this writing there is a possibility that there will have to be additional sessions in January, although these will entail merely the retouching of a few passages.

When completed, this may yet be the most spaced-out recording of Carmen since the monumentally interrupted De los Angeles /Beecham version of over a decade ago.

But whereas the delay in the Beecham enterprise was due in part to temperament, this time the difficulty has been simply the familiar logistical problem: how to assemble a number of expensive talents that rarely have open dates at the same time. Frühbeck de Burgos, who can whip a surprisingly authentic Spanish accent into Bizet's essentially French music, had an important engagement in his native Spain. Mirella Freni, regarded by EMI as a must for the role of Micaela, could not get to Paris for even one session last July. Everything was made a bit more complicated by the fact that only one of the principal members of the cast was French: Eliane Lublin in the role of Frasquita. The Mercédès was the Romanian Viorica Cortez, and Escamillo was the Greek Kostas Paskalis.

Moreover, Jean-Louis Barrault was not available until September, and he was important for an interesting reason.

As everyone knows and usually forgets, some of the dramatic power in Carmen should be credited to the skill of Meilhac and Halévy as librettists. Their skill was originally more apparent than it later became, for the first performance of the work, on March 3, 1875, took place at the Opéra-Comique with the spoken dialogue that was considered proper in that house before our present confusion of genres began.

After the composer's death, however, his friend Guiraud recast the dialogue as recitative, with results that are certainly pleasant enough and often musically effective, but with more than one defect.

The recitatives obscure the story line and the motivation of characters in several places; they make some of Bizet's musical transitions meaningless; they destroy some of his quite Wagnerian psychological effects and some of his verism.

Thus, early in the planning stages, EMI decided that its new Angel album would return to the spoken dialogue of the first 1875 performance. The decision involved doubling the largely non-French cast with French professional actors, since foreign accents that were acceptable when sung would offend all Gallic ears when spoken.

But professional actors trained to deliver lines in plays evidently needed some special direction if they were to manage the style of Carmen. So EMI called upon Barrault, whose experience with the operatic stage and with recorded poetry seemed exactly right for a "conductor" of opéra-comique dialogue on discs.

The singing Don José and the singing Carmen were never a problem for EMI's producers. Vickers made his debut in the role, at the Stratford Festival of 1956.

Bumbry sang her part for the first time in 1960 at Basel in German, and then quickly shifted to French for a performance at the Paris Opéra. With Vickers and Freni she scored a triumph at Salzburg three years ago.

In a conversation during a break at the Salle Wagram she came to some conclusions about the seductive gipsy that would probably have satisfied both Bizet and Merimée: "Naturally, over the years I've altered a hundred or more nuances in my singing and acting. You can't stick to a pattern. But I haven't altered my basic idea of the role. It's a character role. You can't just sing. You are in action all the time. Also, although Don José changes during the course of the opera, Carmen does not. She is the same from the Habairera right through to the end. She is always a girl who loves only herself and her freedom." - ROY MCMULLEN

WARSAW

New Additions to the Polish Repertory

Critics attending performances at the Warsaw Music Festival, devoted to contemporary music (which takes place every fall in the Polish capital), receive a remarkable assist from the state-owned record company, Polskie Nagrania. Within forty-eight hours after each concert, the performances are issued on records-an ideal way to re-enforce one's first impressions of unfamiliar new music. When I arrived in Warsaw at the beginning of October, I was presented with a series of recordings which gave me the opportunity to hear performances that had taken place during the second half of September. These included the world premiere of the Third Symphony by Tadeusz Baird (composed for the Koussevitzky Foundation and completed last April) and Kazimierz Serocki's Poésies, sung by the British soprano Dorothy Dorow and played by the Warsaw Opera Chamber Orchestra.

Polskie Nagrania, founded shortly after World War II, devotes equal attention to avant-garde music, the standard repertoire, and Polish music of all periods.

This juxtaposition of the old with the new strikes the visitor as soon as he enters the building where Polskie Nagrania has set up its main office: an old monastery, part of which is still inhabited by monks of a highly respected order. Two of the firm's executives, Mme. Alina Osostowicz Sutkowska and F. Pukacki, led me into one office room that still strongly resembles a monk's cell. The ensuing conversation, however, was entirely secular, although I had expected that my first question, relating to the record series "Musica Antiqua Polonica," would yield information about plans to record medieval Polish religious music. Mme. Osostowicz-Sutkowska discussed instead a project of a different character altogether. Only recently," she said, "a rather unique collection of seventeenth-century music has been discovered at the Jagellonian Library in Cracow consisting of secular dances, canzonas, and songs. After the music has been transcribed and edited by musicologists, we will record it with the "Fistulatores et fubicinatores Varsovienses." Unearthing musical manuscripts from old archives is also one of the firm's major activities. A case in point is the two-act opera King Lokietek by Joseph Elsner, who founded the Warsaw Conservatory in 1821, and taught harmony and counterpoint to Chopin. King Lokietek has recently been added to the repertory of the Warsaw Chamber Opera and is now being recorded under the direction of Stefan Sutkowski. The record will be released in time to mark the 1970 bicentenary of Elsner's birth.

The influence of Polskie Nagrania upon the operatic repertory in general appears to be remarkable. When the opera house in Poznan prepared to celebrate its fiftieth anniversary, Polskie Nagrania proposed a joint production and recording of an opera by one of Poland's most popular national composers, Stanislaw btoniuszko. The final choice was the one-act opera Verbum nubile, recorded under the baton of Robert Satanowski and released last fall. Moniuszko's works of course occupy a central position in the label's catalogue. Straszny D for (The flaunted Manor), an opera often found in the repertory of the Warsaw Opera, is also obtainable on records.

Hulku, Moniuszko's best-known contribution to the stage, has been earmarked for a new complete stereo recording this season. Another recording project is devoted to a collection of songs that appeared during Moniuszko's life under the title Spiewniki domowe (Song Book fur flume Use) in six volumes; another six volumes containing posthumous works were published after the composer's death. The task of recording these songs has been assigned to the baritone Andrzej Holski, familiar from his performances in numerous recent works by Krzysztof Penderecki.

-KURT BLAUKOPF

------------

(High Fidelity)

Also see: Too hot to handle -- HF answers your more incisive questions