Forgotten Romantics Remembered

[The Romantic piano repertoire rediscovered]

The entertaining, astonishing. exhilarating. and unaccountably neglected repertoire of the nineteenth century

by Harold C. Schonberg

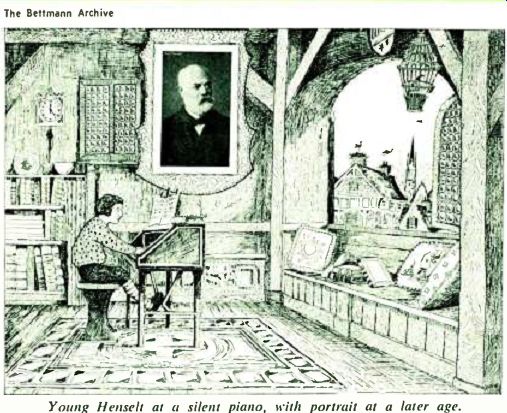

----- The Bettmann Archive: Young Henselt at a silent piano, with portrait

at a later age.

STRANGE THINGS ARE happening. Not long ago the weekly listings of concert programs in the New York Times listed a pianist who had programmed a Kalkbrenner piece Friedrich Kalkbrenner?-and another who was playing a set of Czerny variations: not the Ricordanza that Horowitz had introduced about two decades back but a work unknown even to specialists. Nobody keeps files on this sort of thing, but it is a safe bet that neither had been played in New York for generations, if ever. In Indianapolis there are annual festivals of Romantic music, and the Midwest has been blooming to the tune of Rubinstein's Ocean Symphony and Raff's Im Walde.

In Newport last summer, three concerts a day for ten days explored music by early Romantics, to the bewilderment of the tourists and the vast enjoyment of a handful of Victorian types, who had journeyed for miles to bathe themselves in the lucubrations of such as Karl Reinecke, Peter Cornelius, Camille Saint-Saëns, and Pauline ViardotGarcia. Leonard Bernstein programs Karl Goldmark's Rustic Wedding Symphony (the original German title, Ländliche Hochzeit, is so much more attractive) and Erich Leinsdorf comes up with the Scharwenka B flat minor Piano Concerto. Something is in the air.

And the record companies usually are the first to scent it. They are beginning to think very seriously about minor Romantic music. The baroque craze has about run its course, they are saying, and maybe it is time to cash in on something else. And not on another recording of the Tchaikovsky Violin Concerto or the Stravinsky Firebird. The groaning catalogue of that material is supersaturated. And old memories go back to the success the smaller companies had with the baroque revival, when Corelli, Vivaldi, Locatelli, Fasch, Geminiani, and the others became all but household names. Maybe Hummel, Spohr, Heller, Hiller, Moszkowski, Joachim, Godard, Reinecke? Maybe? Maybe? Maybe. The toe is already in the pool, as witness the simultaneous release of Adolf von Henselt's Piano Concerto in F minor by Columbia and Candide. It used to be a popular work. But like most bravura concertos, it lay forgotten for generations until Raymond Lewenthal revived it at the Romantic Festival in Indianapolis about three years ago. Now he has recorded it, with a much better orchestra. So has Michael Ponti, with the Philharmonia Hungarica and somebody named Othmar Maga. Then there is the Scharwenka B flat minor. Like the Henselt, it had a big run in its time. Old-time critics, headed by James Huneker. adored it. They would gather at Lüchow's and, over great seidels of beer, discuss modern concertos and wonder if any modern composer had ever come up with a theme as beautiful as the second subject of the first movement. Those of us who respond to this kind of music do not take works like the Henselt and Scharwenka as seriously as Huneker and his cohorts. All we claim is that they are fine period pieces, as worthy of exhumation as some dry, formula-ridden concerto grosso of Vivaldi. We say that such music helps bring an age to life, and that it still has validity when approached in the proper, i.e., non-condescending, spirit.

The point about such works is that they do not pretend to anything they aren't. They were written to entertain, astonish, and exhilarate, and they were also written by thorough professionals who themselves were eminent instrumentalists. Those men knew their craft. If they did not have the imagination and originality and earth-moving statement of the big men, they at least could come up with original ideas in the way of technique. Henselt certainly did, and so did Scharwenka.

The Henselt is a good case in point. Adolf von Henselt (1814-1889) was a Bavarian-born pianist who was considered the peer of Liszt and Thalberg. But he had one drawback. He was too nervous to play in public, and he gave very few recitals during his long life. For many years he was resident in Russia, and his influence on the Russian school is a story yet to be told. His technical trick was left-hand extensions. Apparently his hands were not large, but he practiced so much and devoted so much time to left-hand stretches that he could encompass a Rachmaninoffian grasp.

He composed his Concerto around 1840 (nobody seems to have come up with the exact date, but Clara Schumann was playing it by 1844). That makes it about ten years younger than Chopin's F minor Concerto, and the debt is clear. Not only is the key of Henselt's concerto the same but there also is a decided similarity in thematic material. What is different, and amazingly so, is the keyboard approach. It is much more massive, considerably more difficult, and amazingly sophisticated.

A mighty powerful pianist is needed to play this work.

And its material is good. Not very original, but good.

The themes are forceful and attractive. Chopin is combined with some Schumann, Mendelssohn, and Thalberg.

To dislike it for this reason is to dislike Paisiello because he is not Mozart. Whatever its derivations, this Henselt F minor is a strong work with an unexpected amount of charm, and it is a terrific piece for a big virtuoso.

Completely different approaches are offered by the two pianists. Ponti is a literalist, Lewenthal a romantic. Ponti, who does have the notes in hand-more so than Lewenthal, who makes a grander effect but often is blurred-tends toward square rhythms and concentration on detail. Lewenthal worries much less about detail than about the big picture. He is more apt to take a chance, whatever casualties in the way of missed notes occur, and the difference between the two pianists is best illustrated in the last movement. Ponti is deliberate and careful, while Lewenthal, with a much faster tempo, creates a kind of electricity missing from the competition. His playing is also more nuanced (compare the two in the nocturne-like slow movement), with more of a feeling for the Romantic conventions (though he ignores some of the inner voices and stepwise bass progressions notated so carefully by Henselt). Lewenthal adds five measures of piano at the first movement finale.

Ponti, the literalist, stops where the piano part stops.

As between the orchestras, the London Symphony under Mackerras is a much finer group than the Philharmonia Hungarica, and has been given better recording.

Thus, if I had to choose, it would be the Columbia disc. But I shall have to keep both records because of the couplings. Lewenthal has selected the Liszt Totentanz, while Ponti comes up with the first recording in history of the Henselt Etudes (Op. 2). These are fascinating. They come out of Chopin, Schumann, and Mendelssohn, but the piano textures and sonorities look far ahead to Godowsky. All of these Etudes have names (undoubtedly added after the music was composed). The only familiar one is No. 6, Si oiseau j'étais, d toi je volerais. Rachmaninoff and Moiseiwitsch recorded it in the old days, and it is the prettiest of the Henselt Etudes. But others are effective too, and it is surprising that they have dropped from the repertory. Ponti plays them in a rather hard and percussive manner. His finger work is marvelous, but his musical approach lacks the delicate adjustments and tone colors needed for an ultimate statement.

In the Totentanz, Lewenthal has combined the familiar piece for piano and orchestra with another Liszt version.

New material includes a short introduction and a lengthy interpolation in the middle of Variation 27. Lewenthal then picks up at the cadenza, follows with still more new material, and goes from Variation 28 to the end.

Excisions include half of Variation 10 and the chorale-like solo in Variation 22. (In a 7-inch LP that comes with the record, Lewenthal, in his sepulchral bass voice, explains where he got the new material; and he also discusses Henselt in relation to Rachmaninoff and the Russian school.) He plays the Totentanz with virility and tremendous gusto. This is his kind of music, and there is a kind of technical security not always apparent in the Henselt, brilliant as the latter is.

Now the Scharwenka. Xaver Scharwenka (1850-1924) was a well-known Polish pianist and teacher. What student has not at one time or another engaged his Polish Dance in E flat minor? (He recorded it, too, around 1915, for American Columbia.) The B flat minor Piano Concerto dates from 1877, when Scharwenka was twenty-seven. Liszt helped launch the work, and it promptly entered the repertory. It is a large-scale work, colorfully orchestrated, with a murderous piano part.

There is scarcely a rest for the soloist. He has to keep moving in this obstacle course of arpeggios, chords, prestissimo scale passages, leaps, double notes, octaves, and crazy figurations. Scharwenka, like Henselt, may not have been an original thinker, but he knew how to give the pianist a workout. The Scharwenka B flat minor is a fine minor work, considerably more than camp (as has been charged), and belongs with such pieces as the Rubinstein D minor.

I was a little disappointed in the recording. At the actual concert, Earl Wild played with finesse coupled with raw power in the bravura passages. But here the effect is one of raw power only, and that is probably because of the close-up recording. The piano is so favored that it obscures not only details of the orchestration but frequently the entire Boston Symphony itself. Wild is not that percussive a pianist. And what a technician he is! I am told that one of the Boston critics called him a dilettante pianist. If that is so, the same is true of Vladimir Horowitz and Jorge Bolet. Wild's fingers are in that league, and he is not ashamed to display them. In this kind of music, anyway, that would be fatal. The entire effect of the Concerto depends on the pianist's combination of bravura and ability to shape the Romantic kind of melody. Wild delivers. He has the attitude of Moriz Rosenthal, who was once asked if he wasn't ashamed of having so big a technique. "Is Rockefeller ashamed of his money?" Rosenthal answered.

It is too bad that Wild's playing is so overpowering in relation to the orchestra. But at least we have a good idea of what this likable Concerto is about. And Wild has come up with some original material for the reverse side of the record-Balakirev's Reminiscences of Glinka's "A Life for the Tsar," Nicolas Medtner's Improvisation (Op. 31, No. 1), and Eugen d'Albert's Scherzo. The Balakirev is a wild work, thin in substance, fertile in piano resource. Composers all over Europe at the time (1855) were writing operatic potpourris and fantasies, and Balakirev's is representative of the genre.

It does go on a little too long. The Medtner is an attractive work in the Taneiev and Rachmaninoff tradition, and the D'Albert Scherzo, once popular, is a flashy workout and a lot of fun for what it is. Wild plays these three pieces with enormous thrust and virtuosity. In this literature he is a champion athlete.

Ivan Davis' disc, "The Art of the Piano Virtuoso," is a bit of a gimmick record. The idea was to honor eight great pianists by playing a work associated with them.

Chopin is represented by his Andante Spianato and Polonaise; Liszt by his Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6; Clara Schumann by Robert Schumann's Abegg Variations: Anton Rubinstein by Serge Liapounov's Lezghinka: Josef Lhevinne by Moszkowski's Carmen Fantasy; Josef Hofmann by Moszkowski's Caprice espagnole: Rachmaninoff by the Rimsky-Korsakov-Rachmaninoff Flight of the Bumblebee, and Vladimir Horowitz by the Mendelssohn-Liszt-Davis Paraphrase on Mendelssohn's "Mid-summer Night's Dream." Davis has some interesting ideas on playing this material. He has one aspect of the Romantic attitude, in that he is not afraid to touch up the music. In the Liszt Sixth Rhapsody he adds a little cadenza of his own at one spot and, at another, puts a little growl in the bass: a cute touch, that. In the Liszt Midsummer Night's Dream he has made a few cuts and supplied a Horowitz-like ending of his own. The other music he leaves alone. At least one piece on this disc was needed--the Abegg Variations. There does not seem to be an available LP of this remarkable Opus 1. Moszkowski's Carmen Fantasy, based largely on the Chanson bohème, is a tricky show piece. I am glad to have heard it, and having heard it, glad to forget it, much as I like pianistic tightrope walking.

There are many nice things about the Davis performances. He has a spotless technique, intelligence, and an obvious relish for fireworks. Yet he is still too much a child of his time to enter fully into the Romantic world. His tone is a shade too brittle, his touch somewhat percussive, his organization too neat. The quality of improvisation that the old pianists used to get is

missing; nor does Davis have the pedal secrets of a Lhevinne or Hofmann. Everything is scrubbed too clean, and the smile is mechanical, like the smile of the girls in the old Rheingold ads. Pretty, but shallow.

HENSELT: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, in F t minor, Op. 16.

LISZTLEWENTHAL: Totentanz for Piano and Orchestra. Raymond Lewenthal, piano; London Symphony Orchestra, Charles Mackerras, cond. Columbia MS 7252, $5.98. Tape: S MQ 1121, 7 1/2 ips, $7.95.

HENSELT: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, in F minor, Op. 16; Etudes Caractéristiques (12), Op. 2. Michael Ponti, piano; Philharmonia Hungariaa. Othmar Maga, cond. (in the Concerto). Candide CE 31011, $3.98.

SCHARWENKA: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 1, in B flat minor, Op. 32. BALAKIREV: Reminiscences of Glinka's Opera "A Life for the Tsar."

MEDTNER: Improvisation, Op. 31, No. 1. D'ALBERT: Scherzo, Op. 16, No. 2. Earl Wild, piano; Boston Symphony Orchestra, Erich Leinsdorf, cond. (in the Concerto). RCA Red Seal LSC 3080, $5.98.

IVAN DAVIS: "The Art of the Piano Virtuoso." LISZT: Hungarian Rhapsody No. 6; Paraphrase of the Wedding March and Dance of the Elves from Mendelssohn's "A Midsummer Night's Dream." CHOPIN: Andante Spianato and Grande Polonaise brillante, Op. 22.

MOSZKOWSKI: Paraphrase of the Gypsy Song from Bizet's "Carmen "; Caprice espagnole, Op. 37.

SCHUMANN: Theme and Variations on the Name " Abegg," Op. 1.

LIAPOUNOV: Lezghinka, Op. 11, No. 10.

RIMSKY-KORSAKOV: Sadko: Flight of the Bumblebee (arr. Rachmaninoff). Ivan Davis. piano. London CS 6637, $5.98.

Callas and Tebaldi--Yesterday and Today

Two new releases shed light upon the careers of the divas who once monopolized an operatic era.

by George Movshon

---- Callas (right) greets her still-active fariner "rival" Tebaldi,

at opening of Met, 1968. Between them from left: Franco Corelli, Ansehno

Colhani, and manager Bing.

IF RECORDINGS CAN be said to be reflections of a musical age, then both these sets deserve to be encased in amber and kept in a time capsule. Song fanciers of later generations will then have some inkling of what was right, operatically, with our era, and what was wrong. Consider the polarities represented here.

The Tebaldi album is all new and explores some strange territory where few thought she would ever venture.

The Callas album consists entirely of reissued material, a retracing of familiar paths, mostly pleasurable, a few painful.

Tebaldi sings the majority of her selections in Italian, including Wagner, Bizet, and Massenet. The Spanish songs are performed in that language, and the very last bit, If I Loved You, is done in a quaint and captivating variant of our own sweet tongue.

Callas sings each item in its original language--which means the Italian arias in Italian, the French ones in French. (A quibbler could point out that "Convien partir" comes from an opera by Donizetti that began life in Paris with a French text.) The Tebaldi album comes with a fat booklet of few words but over 100 pictures, some of them full-page, and all of her. There is even a happy snap showing her in the company of Maria Callas and Rudolf Bing (see previous page). The Callas album includes an hour-long interview (one complete disc) with Edward Downes, originally broadcast on a Metropolitan Opera matinee intermission several years ago. The interview is at least as revealing of Callas as the pictures are of Tebaldi.

How incredible that these two singers were ever rivals, that the partisans of one rose in the theater to hiss the other, that a feud was believed to rage between them! No two sopranos were ever more dissimilar, nor differed so drastically in style and temperament. Can you imagine cheering mink and booing sable, hailing gouda and scorning cheddar, clapping Laurel and hissing Hardy? Not only were they divergent in approach and manner, but they were in a real sense complementary to each other: each would have been less without the presence of the other in the same art and age. The age-and let us hope it is not yet over-may go down in the performance history of Italian opera as the Callas / Tebaldi period, though there are some (and they are not hard to find) who hold that Milanov and De los Angeles were the equals of the other ladies, and sometimes their betters.

How easy it is to fall into the same trap as the partisans--as I have just done-and start calling one artist "better" than another without bothering to detail what they are better in or better at. And how irrelevant to the simple truth: the opera and the record catalogue need both the silk of Tebaldi at her best and the steel thrust of Callas at hers.

Both are indispensable. Think of Tebaldi as Desdemona (is this not her best role ?) with its melting, limpid pathos; her Puccini heroines, all heart and melody; her Aida and Elisabetta, revealing agony and inner turmoil in the shapeliest musical lines imaginable.

And Callas, whose anger as the betrayed Norma cannot be described in words, whose presence on any stage dominates the action totally, whose inventiveness, insight, and thrusts at truth are unique in opera. Even when her voice says no and refuses to follow her command, she makes her intentions plain. Listen to the appalling flubbed tenuto that ends the Cenerentola aria in this collection-as awful a bleat as you will find on a professional record--and see if you don't agree that what it is really saying is: "There! That's all my voice will allow.

But I am showing you what I intend: that's the important thing." And in the interview record she sums it up more tightly still: "Art," she says, "is more than beauty." As far as one can be sure of such things, both ladies are now forty-six years old, and both have in recent years encountered severe vocal problems. Callas showed trouble first, the high notes deteriorated badly, her repertory shrank, there was a brief flirtation (on records, chiefly), with the mezzo literature, and then ... silence.

She has not sung in public nor has she made any new recordings for some years, though there are rumors and talk now and then of a possible Violetta ... or maybe a Carmen . . . or maybe a Verdi Requiem in Dallas. But so far they have proved just rumors.

In the early Sixties, Tebaldi seemed to lose confidence in her high register. The soft, floated notes vanished and a new, hard element became apparent in the voice. Over much of the range it was still the loveliest soprano sound imaginable; but in approaching anything above the stave she tended to tighten up and belt out the notes. Judging by these records, things are still not entirely right-and perhaps they never can be. But she is again capable of achieving a melting beauty at the top of the range.

That is clear in the closing notes of Dalila's second aria, where she takes the high option most beautifully.

The Callas discs, as noted, are all reissues and they are drawn from complete recordings and recital discs originally made between 1953 and 1961. The performances are classic and irreplaceable, showing a great artist in a wide variety of her roles: all told they amount to a strong portrait of Maria Callas, depicting justly both her glories and her deficiencies. Callas fans will have most of this material already; and what is more they will have acquired the knack of listening past (or through) the vocal wounds to the noble concept that often lies beyond. The interview is most informative. Technically, the transfers have been cleanly done, and the mono items have been rechanneled with commendable conservatism and restraint.

Tebaldi requires more elaboration. The Wagner items (once the novelty has worn off) are quite easy to listen to, though they are not deeply conceived or strikingly revealing. Elisabeth's greeting lacks boldness, but Elsa's Dream has a fine, visionary quality, especially at the last modulation. Tebaldi has sung in Italian performances of both Tannhauser and Lohengrin, but she has not done an Isolde and is most unlikely to. Yet the Liebestod fits her emotional nature like a glove, and she sings the soft contours of this scene with outstanding loveliness. It still sounds strange in Italian, but the vocal quality is delectable.

The French items are less commendable. Tebaldi finds a good chesty rasp for Carmen in the Habanera but it really isn't done with the necessary pointed sexiness; hers is a ladylike Carmen, more likely to take tea than a romp in the hay. And Guadagno's accompaniments, both here and in the Dalila songs, tend to sag. There is a lot of good singing tone in the Saint-Saëns but nowhere near enough intensity. Best of the French lot is the Massenet pair, with Tebaldi most poetic in the petite table apostrophe but spoiling things with a dramatic gasp at the end.

Aïda's "Ritorna vincitor" is an acceptable interpretation, but not to be compared with her 1959 reading (for Karajan), which in turn was a notch below her 1952 versipp for Erede. Musetta's Waltz lacks sparkle and does not take off. The three songs of Rossini's Regata are most enjoyable and Tebaldi conveys much, if not all, of the humor. The Spanish songs (as well as the Italian ones and the Richard Rodgers) tend to be a bit overpowering -- Granada in particular--but there is still much to like.

Tebaldi fanciers will want it all. For the others, a single disc might have been enough.

RENATA TEBALDI: "A Tebaldi Festival." WAGNER: Tannhauser: Dich, teure Halle; Allmacht'ge Jungfrau; Lohengrin: Elsa's Dream; Tristan und Isolde: Liebestod.

BIZET: Carmen: Habanera; En vain pour eviter.

SAINT-SAENS: Samson et Dalila: Amours, viens m'aider; Mon coeur s'ouvre à ta voix.

MASSENET: Manon: Adieu, notre petite table; L'Oiseau qui fuit. VERDI: Aida: Ritorna vincitor. PUCCINI: La Bohème: Musetta's Waltz.

ROSSINI: La Regata Veneziana. LARA: Granada.

POCE: Estrelita.

CARDILLO: Catari, catari. TOSTI: A vuchella.

DE CURTIS: Non ti scordar di me.

RODGERS: Carousel: If I Loved You. Renata Tebaldi, soprano; New Philharmonia Orchestra, Richard Bonynge and Anton Guadagno, tonds. London OSA 1282, $11.96 (two discs). MARIA CALLAS: "La Divina."

BELLINI: Norma: Casta diva; Dormono entrambi; I Puritani: Qui la voce ... Vien, diletto.

VERDI: II Trovatore: D'amor sull'ali rosee; Ernani: Lrnani, involami.

ROSSINI: II Turco in Italia: Non si da la follia; La Cenerentola: Nacqui all'affano ... Non più mesta.

DONIZETTI: Le Figlia del reggimento: Convien partir. MOZART: La Nozze di Figaro: Porgi amor.

GLUCK: Alceste: Divinités du Styx.

GOUNOD: Faust: Jewel Song.

THOMAS: Hamlet: A vos jeux ... Partegez-vous mes fleurs. Maria Callas in conversation with Edward Downes. Maria Callas, soprano; Philharmonia Orchestra; Paris Conservatoire Orchestra; French National Radio Orchestra; Nicola Rescigno and Georges Pretre, cond. Angel SCB 3743, $11.96 (three discs).

Must A Great Violinist Play In Tune?

by Robert C. Marsh

Yes, as Zukerman demonstrates

VIOLINISTS CAN BE DIVIDED into two groups: those who play precisely on pitch and those who do not. While there may be great artists in both groups, for my taste, tightly focused pitch is often the indispensable key to the highest levels of interpretive success.

Pinchas Zukerman has it. You can listen to him for the pure and simple pleasure that comes from hearing every note fall precisely in place as if it were governed by a crystal-controlled oscillator circuit. Of course there is more to Zukerman than that. Not only has he exceptional mastery of intonation, he has exceptional mastery of everything that goes into playing a violin--superb control of the bow and the ability to match tone quality with musical content through the sensitive application of vibrato.

In this debut recording, the Tchaikovsky Concerto provides the best examples of the way in which Zukerman sees a phrase as a flowing sequence of tones, each of which must be produced in a slightly different manner--a little vibrato more or less, an adjustment in the bow, an unusually apt fingering-to yield the specific musical results he has in mind. His harmonics are accurate and gorgeous.

Significantly, when there is a slight departure from written pitch, it is upward, a revealing contrast to the legions of violinists who tend to play flat or conceal fuzzy intonation under a consistently wide vibrato.

Zukerman knows how to produce beautiful sounds, but he also knows that tonal opulence means little unless guided by musicianship, and thus his response to a given passage always seems calculated in terms of his total view of the work. There is no show of fine fiddling for its own sake.

It follows that both these performances are extremely rewarding, among the best in the catalogue, both musically and (believe it if you will) intellectually stimulating to a high degree. The excitement obviously carried over to the orchestras and conductors involved. Dorati and the Londoners provide first-class support in the Tchaikovsky, and Bernstein, an exemplary Mendelssohn conductor when properly motivated, comes up with an unusually fine account of the orchestral portion of the Concerto. Both works are extremely well recorded. with the soloist forcefully projected without distorting the natural balances of the score. This could be the most important debut recording of the season.

MENDELSSOHN: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, in E minor, Op. 64.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, in D, Op. 35. Pinchas Zukerman, violin; New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein, cond. (in the Mendelssohn); London Symphony, Antal Dorati, cond. (in the Tchaikovsky). Columbia MS 7313, $5.98.

by Harris Goldsmith

-----------

Not if he's Thibaud

THE STYLISTIC revolution, vis-à-vis performance practice, has affected string playing to an even greater degree than it has pianism. Over the years, the attitude toward shifting and sliding, in particular, has changed from one of warm tolerance to almost total self-denial. And today, while many fiddlers think nothing of using a wide vibrato, the extravagant yet genuinely musical portamento used here by Jacques Thibaud (1880-1953) would doubtlessly inspire derisive laughter from those sane "enlightened" souls. Moreover, it cannot be denied that Thibaud was not overly fond of practicing. The violinist's compatriot, Pierre Monteux, made it quite plain that Thibaud--a champion tennis player-far preferred that game to violinistic drudgery. And, to be sure, on this disc Thibaud does not always play in tune. Yet there is so much mind, heart, and intellect in these readings that I will gladly overlook all the squeezed tones and intonational lapses-and even the questionable cadenzas in the Concerto-for the joy of the performances. I urge all sensible music lovers to hear this recording.

If they can make allowances for the démodé instrumental address and also for the fact that Thibaud is rather off form in the Chausson, they will rediscover one of the century's sublime interpretive souls. Thibaud's sweet, pungent sound and exalted élan produce an elevated, aristocratic Mozart and a Chausson Poème with more genuine strength and less sentiment than one ordinarily hears.

Both accompaniments are sympathetic and unpolished, with Paray's Mozart the better of the two. The sound (from early postwar Polydor shellacs) is dated but kindly. The Mozart, especially, has a warm ambience behind its whiskers.

MOZART: Concerto for Violin and Orchestra, No. 3, in G, K. 216.

CHAUSSON: Poème for Violin and Orchestra, Op. 25. Jacques Thibaud, violin; Lamoureux Orchestra, Paul Paray, cond. (in the Mozart); Eugene Bigot, cond. (in the Chausson). Turnabout TV 4257, $2.98 (mono only).

-------------

(High Fidelity)

Also see: CLASSICAL REVIEWS