reviewed by:

ROYAL S. BROWN, ABRAM CHIPMAN R. D. DARRELL PETER G. DAVIS SHIRLEY FLEMING, ALFRED FRANKENSTEIN KENNETH FURIE CLIFFORD F. GILMORE HARRIS GOLDSMITH, DAVID HAMILTON, DALE S. HARRIS, PHILIP HARI PALL, HENRY LANG ROBERT C. MARSH, ROBERT P. MORGAN, ANDREW PORTER H. C. ROBBINS LANDON JOHN ROCKWELL, SUSAN THIEMANN SOMMER

--------

Explanation of symbols

Classical:

Budget

Historical

Reissue

Recorded tape:

Open Reel

8-Track Cartridge

Cassette

-----------

----------- Antonio Barbosa Obvious talent but variable Beethoven.

BARTOK: Duos for Two Violins (44). Lorand Fenyves and Victor Martin, violins MUSICAL HERITAGE MHS 1722; $3.50 (Musical Heritage Society. 1991 Broadway, New York, N Y. 10023). Comparison: Allay Kuttner: Bartok 907

Bartok is unique among major composers in that he maintained throughout his career an interest in venting music for children, designed especially for pedagogical purposes. Since he was himself a pianist, who made his living for a significant portion of his life teaching his instrument, it is not surprising that most of his output in this area was limited to pieces for piano. Best known of these are of course the six volumes entitled Mikrokosmos. But there are mans sets of a similar nature e.g.

Unfortunately, Bartok wrote only one set of pedagogical pieces for an instrument other than his own the forty-four duos for two violins. Arranged (like Mikrokosmos) in order of ascending difficulty. they are masterpieces of their type. Although each is written so as to concentrate on a special technical problem, such as a particular mode of articulation. one nexer senses that the composer is writing down to his performers.

Each little piece makes a serious, if often simple, musical statement: and each is distinctly contemporary and specifically Bartokian in both sound and character. Moreover, the 44 duos reveal an amazing vatiety. There is a wealth different textural arrangements, and man different compositional techniques (canon, simultaneous combination of different modes or meters, etc.) are illustrated. As in all of Bartok's instructional music, much of the material here is derived from folksong. hut. as is so frequently the case with this composer. the folk elements are so beautifully integrated into the compositional style that one is scarcely conscious of their presence.

This new recording of the duos by violinists Lorand L and Victor Martin serves the set very well. The players present the music in generally straightforward manner than provide a helpful model for young violinists struggling with the pieces. Since the work is performed in its published order. However, there is a problem from the listener's point of view: The methodical progression from the simple to the more complex is hardly conducive to formal variety.

In the old Victor Ajtay-Michael Kuttner version, still listed in Schwann-2, the set is arranged so that it begins and ends with more difficult pieces. the easier ones being distributed throughout the middle. This is certainly preferable for concert purposes. hut unfortunately the sound quality- there is not up to that of the new version. The latter, recorded in Spain, is excellent.

-R.P.M.

BARTOK: For Children, Vols. 1-2. Ylda Novik, piano. TOSHIBA 7032 and 7033, $5.00 each.

BARTOK: Mikrokosmos (complete). Ylda Novik, piano. [M. Hanada, prod.] TOSHIBA TS 7042 ,3, $10.00 (two discs. manual sequence). (Both available from Dano Co.. 4805 Grantham Rd., Chevy Chase. Md. 20015.)

For Children, composed in 1908-10, is music that cannot he fully understood without some acquaintance with Hungarian folk music. The folk elements are not "arranged" or "elaborated." but are melted into the style: they mirror the innermost world, the spirit of age-old aboriginal music, reflected in the strong inclination to pentatonic melodies. Manx of these melodies are neither major nor minor, but in the modal vein of East European folksong.

While these pieces seem simple, they are also very sophisticated and full of melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic subtleties: the usual pianistic approach to "little pieces" falls far short. There is a nervous energy in the smallest of them. the melodies are intensive, the harmonies organic, not experimental, and to articulate the plain lines properly the performer must summon his whole arsenal of musicianship.

-------- Stuart Burrows A mellifluous Faust

Ylda Novik does only partial justice to these artistic requirements, or she sentimentalizes what is straightforward music having little in common with Romantic piano pieces. Many years ago, I frequently heard these pieces played by children for Bartok, who urged them to avoid any pussyfooting-he wanted a solid and often percussive sound. Indeed, these compositions count upon the bright innocence of children unspoiled by "educational materials." ( Bartok customarily urged them to play Bach inventions, Scarlatti, etc., and avoid the usual bland fare).

Novik employs rubato--as she should-but in this music the rubato is quite different from the type used in the nineteenth century. Cadences must be positive and snappy. not splayed out: pauses before the last chords are taboo; chords must not be separated from their melodic tones. On the other hand, there should be good variety of tempo. even within phrases. Novik plays well, but she is not quite sure of herself idiomatically. The modal melodies are indifferently phrased, and her tone is somewhat neutral, not the narrative tone of the folk tale that is obviously indicated. This music too has a tempo giusto as in the eighteenth century, which in both instances is difficult to indicate even with the metronome.

Mikrokosmos starts inauspiciously. Knowledge of Gregorian chant would have helped the pianist to delineate these monophonic melodies: in her rendition they are dull and lifeless. Not altogether surprisingly. she does much better with the technically difficult numbers in the last third of the set. These are etude-like modern piano pieces, a style into which our younger pianists are born. Moreover, in this part of Mikrokosmos (composed in 1937) Bartók returns to a more conventional idiom. Now Novik's tone acquires more sub stance and color. her rhythm sharpens. she displays agility and a nice leggiero, so what started as a dull litany ends in an enjoyable performance.

These discs are a Japanese release, with only the titles given in English. The recording itself offers good sound. though it is somewhat marred by echo of both varieties.

-P.H.L.

BEETHOVEN: Sonatas for Piano: No. 21, in C. Op 53 (Waldstein ): No. 30, in E, Op. 109. Antonio Barbosa, piano. [E. Alan Silver, prod.] CONNOISSEUR SOCIETY CSQ 2068, $6.98 (SQ-encoded disc).

It is hard to believe that these two performances come from the same player.

Barbosa's Waldstein is, on the whole, rather successful. While his greatest affinity is for swashbuckling Romanticism rather than de tailed classicism, he displays commendable attention to detail. This is a rather rhetorical reading, and, though certain edges are rounded off in a too generalized manner, enough angularity remains, along with such niceties as the unusual on-the-beat execution of appoggiaturas in the first movement, the careful delineation of inner voices in the Adagio, and the correct placement of the crucial sforzandos near the end of the rondo. Barbosa also seems (it is difficult to tell without visual aid) to play the octaves glissando and to hold the sustaining pedal through the changing chords as directed by the composer. In the third return of the rondo theme he follows the manuscript over the first printed edition, retaining the loud-soft alternation that the standard version smooths away to a constant piano; I couldn't agree more-this variant is much more effectively dramatic.

I suspect that Barbosa has not lived with Op. 109 as long. In any event, the performance shows little of the insight of the Waldstein. The first movement progresses in a tinkly, prosaic manner, with more emphasis on individual notes than on sentences and paragraphs. The Prestissimo (which, curiously, is listed neither on the record label nor in the timings) gets a suitably spirited tempo and some clean playing, but once again sounds more like pianism than music-making. The variations are marked andante motto cantabileed espressivo, but Barbosa ought to be reminded that andante doesn't mean slow. The performance drags when it doesn't actually disintegrate into episodes. Connoisseur Society is doing its obviously talented young artist a disservice by recording him too soon in such demanding repertory.

The instrument itself has a rather drab tone (the treble especially thins outs unpleasantly), which is even more damaging in the lyrical Op. 109 than in the sturdily extroverted Waldstein. And once again the Connoisseur Society pressing is substandard.

-H.G.

BEETHOVEN: Sonata for Piano, No. 7; Variations in C minor, WoO. 80; Bagatelle "WI' Elise"; Rondo a capriccio, Op. 129-See Franck: Symphonic Variations.

BEDFORD: Tentacles of the Dark Nebula See Lutoslawski Paroles Tissees

BERKELEY: Four Ronsard Sonnets-See Lutoslawski: Paroles Tissees.

BERLIOZ: La Damnation de Faust, Op 24 Marguerite Faust Mephistopheles Brander Edith Mathis Stuart Burrows (t) Donald McIntyre (b) Thomas Paul (Os) Tanglewood Festival Chorus; Boston Boy Choir; Boston Symphony Orchestra, Seiji Ozawa, cond. [Thomas W. Mowrey, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2709 048, $23.94 (three discs, manual sequence).

When I first heard of DG's intention to record the major Berlioz works in Boston with Seiji Ozawa. I was dubious-not because of any lack of respect for either conductor or orchestra, but because the existence of Colin Davis' really first-rate recordings would seem to have pre-empted the market for some time. Why spend hard-to-come-by resources on duplicating that magisterial series for what will probably be a limited number of purchasers, unless, of course, DG could offer something rather special to justify the duplication, to cajole buyers into acquiring a second Damnation and whatever else is to follow? A big "unless," and not really filled by this first installment. True. a good deal of Stuart Burrows' mellifluous Faust must be accounted superior to the somewhat strained efforts of Nicolai Gedda, though when the crunch comes in "Nature immense" the Welsh tenor can't quite muster his counterpart's sheer authority. (He also runs into some discomfort over the top C sharp in the love duet, but this is a quickly passing flaw.) Although Edith Mathis is a wonderful, musicianly artist, her voice is all wrong for Marguerite: The part's top notes. where we should sense a certain strain, give her no difficulty at all, while the lower-register writing, which represents the character's vocal "home base." as it were, drives her into pushing her tone to a point where a palpable beat enters the sound.

For all its skill and sensitivity, this performance misses the point. And Donald McIntyre, in rather good voice, never conveys much of the volatile nastiness of his part.

But then, little about this performance can be called volatile; hardly ever does the choral liozian verve, accurately though most of it is executed (here and there, notably in the Menuet des Feux-Follets, one could wish for better wind intonation and ensemble). Little of the phrasing has reach and thrust; everything just lies there--you know it will get to the end, but you don't feel any sense of destination.

The recorded sound is "imposing"--that is, a brave, but not entirely clear, noise. There's a good deal of miasma floating around the hall, especially in the choral episodes (e.g. the chorus of students comes up mostly a generalized fog of B flat major).

I'm sure that in the concert hall this performance had its points-indeed, the opportunity to hear a big Berlioz score "live." even in a performance rather less good than this one, is not something I would pass up. When it comes to records, however my allegiances will stay with the Davis set (Philips 6703 042)..

-D.H.

BIZET: Carmen-See Verdi: Rigoletto.

COUPERIN: Les Nations. Quadro Amsterdam (Frans Bruggen, flute and recorder; Jaap Schroder, violin; Anner Bylsma, cello; Gustav Leonhardt, harpsichord); with Marie Leonhardt, violin; Frans Vester, flute. TELEFUNKEN TK 11550, $13.96 (two discs, manual sequence) [from SAWT 9476 and 9546. 1969].

La Francoise; L'Espagnole; L'Imperiale; La Piemontoise.

Comparison:

Dart Olseau OLS 137/8 Francois Couperin's set of four ordres called Les Nations, Sonades et Suites de Simphonies en Trio was published in 1726, though some of the pieces were actually written more than thirty years earlier. In 1692 Couperin had composed some sonate da chiesa in the Italian manner, using the similar works of Corelli as a model. They were predominantly contrapun tal in style and comprised six to eight contrasting movements, played without interruption.

Later it occurred to him to add to each of these "Italian" sonatas a suite of dances in the French style in order to achieve a "reunion des goats." To further emphasize the inter nationalism, he named the sonatas after four of France's nearby nations.

Couperin's published score calls for two "dessus" (melody) instruments, a "basse d'archet" (bowed bass), and a keyboard instrument. leaving it to the performers to choose flutes or violins (or oboes?) for the "dessus" parts. cello or gamba for the bass, and harpsichord or organ for the figured bass part. Thurston Dart, in the Oiseau-Lyre recordings, uses two violins, gamba, and harpsichord throughout: whereas Leonhardt. in this newer Telefunken set, has two flutes (and a recorder) and two violins to share the upper parts, and a cello and harpsichord for the bass.

The Dart recordings were made in the early '60s and were reissued about a year ago. Dart was a brilliant musicologist as well as a gifted performer, and his vigorous and incisive readings of these fascinating pieces are among his very best. In the early '60s these performances were really quite daring and controversial, with their elaborate ornamentation and many rhythmic alterations, and even today there are few performers who understand the stylistic peculiarities of this music as well as Dart did then.

Leonhardt's Telefunken recordings were made in 1968 and originally released on two single discs (SAWT 9476 and 9546). The Amsterdam-based group turns in even more vigorous, more highly polished, and better sounding performances than Dart's ensemble.

It frequently chooses even faster tempos, and its ensemble playing is utterly perfect. The re corded sound. too, is more modern, though the Oiseau-Lyre sound is also quite good.

Leonhardt and his players are scholars and experts on early music and understand perfectly the stylistic requirements of Couperin's music.

It would appear that Dart's recording has been superseded by this superb new (well, newer) Telefunken set, but there are some in tangibles involved that are difficult to de scribe. Perhaps because Dart made these recordings more than a decade ago. when so few people understood what he was up to, there's a certain cockiness or audacity in his performances, especially with regard to the variety of rhythmic alterations, compared to which the Telefunken recordings sound rather staid and conservative. It's that feeling of ad venture. the challenge of sailing uncharted seas, that makes his performances so special.

Both recordings are superb, and I'm glad .to have them, but it is clear that Dart's version is the one I'll return to most often.

-C.F.G.

DEBUSSY: Orchestral Works, Albums 1-2.

Orchestre National de l'ORTF, Jean Martinon, cond. [Rene Challan, prod.] ANGEL S 37064 and S 37065, $6.98 each.

Album 1: Children's Corner Suite (orch. Caplet): Petite Suite (orch. Busser); Dance (Tarantelle styrienne) (orch. Ravel), La plus quelents (with John Leach, cimbalom); Berceuse heroque.

Album 2: Fantasy for Plano and Orchestra (with Aldo Ciccollni); Rhapsody for Clarinet and Orchestra (with Guy Unpin); Rhapsody for Saxophone and Orchestra (with Jean-Marie Londeix); Danses sacrbe et profane (with Marie-Claire Jamet, harp).

Comparison:

Froment/Luxemburg Radio Orch. Vox SVBX 5127, 5126; Can. CE 31089 In a prophecy that will go down with the 1948 Dewey election-victory forecast, I concluded my October 1974 review of the mostly unin spiring Froment/Vox Debussy orchestral survey: "It may even be unrealistic to hope that the job will be someday done even better." Unrealistic or not, someday seems to have arrived, Jean Martinon is today's ranking French conductor, and whatever the short comings of the National it is an orchestra of fuller tone and greater elan than Froment's Luxemburgers. Angel's sound too has more body than Vox's, and, more significant. Angel has made what I consider generally more sen sible decisions about what to include.

The Martinon survey, which is being re leased here on single discs (Albums I and 2 are reviewed here: Album 3, scheduled for March. will contain the Images and Jeux). has already appeared in England as a five-disc set.

Though Froment takes seven discs (two Vox Boxes plus a Candide single), Vox offers only three works not recorded by Angel. while An gel offers four not included by Vox-all, as it happens, in Albums 1 and 2.

Two of Angel's omissions are un-exception able. There was little reason for Vox's inclusion of two orchestral excerpts from L'Enfant prodigue and even less justification for Froment's hybrid melange from Le Martvre de Saint Sebastien. I do. however, regret the absence of the much neglected Le Triomphe de Bacchus. There is considerable compensation, though, in Angel's offering of one work inexplicably omitted by Vox-the exquisite little Danses sacree et profane (Album 2)-and three works excluded rather arbitrarily by Vox because they were not orchestrated by Debussy (a rule by no means strictly adhered to): the Children's Corner Suite. Petite Suite, and Dance (all on Album 1).

Not everyone will want the Caplet orchestration of Children's Corner. The six movements thereof are highly pianistic ("Gradus ad Parnassum" by definition) and ought to be heard that way. Caplet did succeed, however, in creating a charming atmosphere in "Serenade for the Doll" and effectively used the obvious low-strings and wind solutions, respectively, for "Jimbo's Lullaby" and "The Little Shepherd." Martinon makes a strong case for Caplet's work.

Busser's orchestration of the Petite Suite is better known, and deservedly so. I believe it suits the choreographic grace and gentleness of the music even better than did the two-piano original. Unfortunately, this isn't one of Martinon's better performances, for there is untidy ensemble and the rhythmic arteries seem clotted. Ansermet (London CS 6227, coupled with various items by Faurt) is rec ommended for those in search of just this score, though even he has been surpassed by Paray (on a deleted Mercury stereo disc) and Reiner/NBC (on an RCA mono classic).

Ravel's scoring of the little Danse (Taran telle styrienne) is one of my favorite examples of quintessential Gallic sparkle.

The remaining two items on Album 1. also orchestrations of piano pieces, were in the Vox series, because Debussy did the orchestrating himself. Martinon plays the waltz La plus que lente more slowly and sensuously, and the strangely touching Berceuse herolque too is more appropriately grave than in Froment's nervous and unsteady rendition.

Martinon's Album 2 competes directly with the Froment single disc of the piano fantasy and clarinet and saxophone rhapsodies, except that Angel includes, as noted, the Danses sacree et profane. Saxophonist Jean-Marie Londeix. who also appeared with Froment, here attains a mellower and more suavely shaded tone color. Angel's clarinetist. Guy Dangain, gives a bolder, more fluent interpretation than Candide's Serge Dangain (any relation?). The plasticity and warmth of Martinon's views on this literature extend to the two Danses, which have a fine lilt, but here some may prefer the more severe and tough minded classicism of Boulez/Cleveland ( Columbia MS 7362).

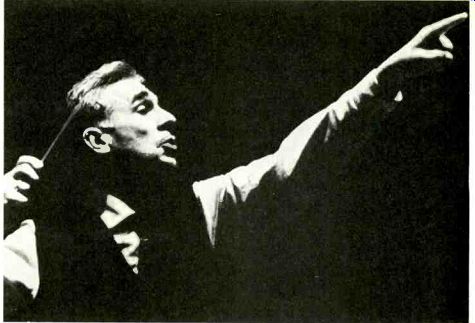

--------- Jean Martinon-Debussy with plasticity and warmth.

I have mixed reactions to Angel's piano fantasy, which takes up all of Side 1. Aldo Ciccolini's touch is brusque and hammer-like, his phrasing fitfully angular. in a piece that calls more for the easy and unostentatious legato of Maryline Dosse (Candide) or Jean-Rudolphe Kars (London CS 6657. coupled with the Delius concerto). Also, the piano has a dis tinctly brittle clang. However, Froment's conducting is so pale and dry (and Gibson's for Kars a bit too refined and smoothed out) that Martinon's bold, sweeping rendition, with its gleamingly "French" orchestral sound, has to take pride of place.

-A.C.

DEBUSSY: Pelleas et Melisande. For a feature review, see page 76.

ELGAR: Enigma Variations, Op. 36. R.

STRAUSS: Don Juan, Op. 20. London Philharmonic Orchestra (in the Elgar), Concertgebouw Orchestra (in the Strauss), Bernard Haitink, cond. PHILIPS 6500 481, $7.98.

The present coupling represents two of the most recent streams flowing into the impressively accumulating reservoir of Haitink's re corded repertory: Richard Strauss tone poems and favorite English orchestral works. The Don Juan, with the conductor's Amsterdam Concertgebouw, matches the exceptionally high executant and technical standards set by their recent magisterial Also sprach Zarathustra and so must rank among the finest versions, lacking only something in the way of melodramatic frenzy that many romantically minded listeners demand here. Haitink's Elgar, for which he wisely shifts to "his" other orchestral, the London Philharmonic, was foreshadowed by his 1971 Holst Planets with the same orchestra and reveals similar stylistic affinities as well as the conductor's characteristic eloquence and complete surety of control.

The Enigma Variations have been so long associated with the generally more heart-on-sleeve Barbirolli, Boult, and Sargent readings that many aficionados of the work may find Haitink unduly reserved at first hearing. But before long even they are likely to realize that his less overtly expressive approach is in actuality more robust and dramatically persuasive than the more familiar ones. In any case, none of the earlier versions comes close to this one's tonal resplendence. Here even the bombast of the final, autobiographical variations (so incongruously contrasted with the scoring restraint of the rest of the work) is at least spectacularly awesome sonically.

-R.D.D.

FRANCK: Symphonic Variations.

LISZT: Totentanz. Andre Watts, piano; London Symphony Orchestra, Erich Leinsdorf, cond. [Paul Myers, prod.] COLUMBIA M 33072, $6.98. Tape: El MT 33072, $7.98; t.r MA 330,2, $7.98. Quadriphonic: MO 33072 (SQ-encoded disc), $7.98; MAO 33072 (0-8 cartridge), $7.98.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 1, in B flat minor, Op. 23. Andre Watts, piano; New York Philharmonic, Leonard Bernstein, cond. [John McClure, prod.] COLUMBIA M 33071, $6.98. Tape: ino MT 33071, $7.98; 3 MA 33071, $7.98. Quadriphonic: MO 33071 (SQ-encoded disc), $7.98; MAO 33071 (Q-8 cartridge), $7.98.

BEETHOVEN: Sonata for Piano, No. 7, in D, Op 10, No. 3, Variations (32) in C minor, WoO. 80; Bagatelle "fur Elise"; Rondo a capriccio, in G, Op. 129 (Rage over a lost penny). Andre Watts, piano. [John Corigliano, prod.] COLUMBIA M 33074, $6.98.

SCHUBERT: Fantasy in C, D. 760 (Wanderer); Sonata for Piano, in A minor, D. 784; Waltzes (12), D. 145. Andre Watts, piano. [Paul Myers, prod.] COLUMBIA M 33073, $6.98.

Of these four new Andre Watts releases, one the Franck/Liszt coupling-warrants an enthusiastic recommendation. The Liszt Torentan: is especially brilliant. Here is a piece that can absorb Watts's high-voltage technique without harm. What bravura he brings to its pages! The octave passages are particularly impressive in their blazing speed and accuracy. But Watts, thankfully, sees more in the piece than mere possibilities for display: He realizes the intellect behind these Dies Irae variations, the jagged textures, the daring harmonic innovations, the brooding experimentation that foreshadows not only the later Liszt, but the piano music of Debussy, Bartok, and Kodaly as well.

The Franck may not be as tonally supple as in some readings-the recent De Larrocha (London CS 6818) and the ancient Cortot/Ronald and Gieseking/Mengelberg particularly come to mind. But, as in the Liszt, Watts appears to be using an instrument with more vibrant coloristic resources than on these other records, and his clear-cut phrasing and digital accuracy are always welcome.

Leinsdorf is a splendid partner. He leads both scores with power and efficiency, getting wonderfully clean attacks and releases from his players. Brilliant, airy, well-defined sound too-and the best pressing of the four discs.

Bernstein is obviously the dominant partner in the Tchaikovsky concerto, and it is he rather than Watts. who sets the (wrong) pace of the performance. This is the Tchaikovsky B flat minor as Klemperer might have done it, which is. I suppose. preferable to the way Bernstein has done it-with Entremont on disc or with Gilels at a 1955 U.N. concert. The tem pos may be slow-to-the-point of utter stagnation and the structural aspects of the work unearthed with creaking rigor, but at least the textures are reasonably clear this time and there is none of that gushing sentimentality of yore. The New York Philharmonic plays better this time too, though there is one notably had patch of sloppy ensemble (first-movement recapitulation. second theme) that should have been remade.

Watts supplies accurate solo playing but little that is memorable. His tone is mono chromatic and unimaginatively voiced. Conductor and pianist were apparently seeking breadth and monumentality. but they wound up sounding merely listless and lumbering.

Some of the Beethoven and Schubert solo pieces have no doubt been in the Columbia icebox for a while, perhaps going back as far as 1966, when Watts played the Beethoven Op. 10. No. 3 Sonata and the Wanderer Fantasy at Philharmonic Hall. In any event, the re corded Beethoven seems better judged than that live performance. though the Schubert suffers from many of the immaturities of phrase and pacing I recall.

The Beethoven sonata receives an honest, robust reading with clean finger-work and suit ably brisk tempos in the outer movements.

The weak spot is the great Largo e mesto, which is a trifle literal in its phrasing and flinty in sound. The succeeding scherzo begins in a rather glib, brittle fashion-almost as if the pianist were totally unaffected by the movement just played. The recent versions of Ashkenazy ( London) and Hungerford (Vanguard) and the great older ones of Arrau (Philips) and Schnabel (Seraphim) are all, in their various ways. more magical and perceptive.

The so-called Rage over a lost penny. on the other hand, is brilliantly done. The tempo is again very fast-in the Schnabel manner-and yet always controlled and articulated. This is a performance full of scurry and humor. but the logical internal development of the thematic material is also beautifully dealt with.

The C minor Variations, which need a chaconne-like solidity tempered by an instinctive yield and flow in the more lyrical episodes, suffer from some rather arbitrary distortions of tempo and, in general, from pianism that tends toward brittle efficiency and metronomic rigidity (despite the attempted "expressive" rubatos). Fur Elise is rather wan and precious; moreover. Watts opts for a recurrent D instead of E. whose authenticity I question even though it appears in the usually reliable Henle text.

The Schubert disc begins with a series of waltzes played in a rather artful. overly pointed way. The worst performances of "Viennese" music, of course, are those from Viennese musicians. but foreigners are catching on. I wish Watts had followed his natural bent and torn through these vignettes in an un fussy. metronomic manner. At least the performances would have been less pretentious.

The Wanderer Fantasy lacks the big line.

Watts inserts diminuendos at climactic places instead of continuing to build fearlessly to his harmonic destination. Slow sections go limp (and thus become tinged with sentimentality), and many of the bravura sections forge ahead without any real feeling of pulse or rhythmic definition. This is a terribly difficult virtuoso piece. of course. and Watts. to his credit. does furnish fleet finger-work and some textual niceties--e.g.. he changes the D sharp to D natural in the last measure of the second movement (which makes far more harmonic sense than the "misprint" version did).

When wit/Columbia reissue the finest Wanderer of all: the performance by Watts's teacher. Leon Fleisher?

-H.G.

GERSHWIN: Orchestral Works. Jeffrey Siegel, piano*: St. Louis Sym phony Orchestra, Leonard Slatkin, cond. Vox QSVBX 5132 $10.98 (three OS-encoded discs).

An American in Paris: Catfish Row; Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, in F'; Cuban Overture; Lullaby. Promenade; Rhapsody in Blue': Second Rhapsody'. Variations on "I Got Rhythm".

We hear a lot about performance practices in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. but this album would benefit from more attention to performance practices in the 1920s and '30s.

I don't suggest that its contents are significantly worse--or better-than most Gershwin performances one encounters in the schedules of American symphony orchestras.

They are, distressingly. typical of such events, with competent. conservatory-type musicianship applied to works that demand the flexible, quasi-improvisatory playing of the well-seasoned sideman: in consequence. they are slightly solemn, square. and pretentious when they ought to sing and Banish once and for all the idea that a young American conductor of great talent, which Leonard Slatkin undoubtedly is. automatically knows how to play Gershwin. The period is not part of his direct life experience, and his approach is through study-precisely the same way he would approach Vivaldi. Pianist Jeffrey Siegel is somewhat more deeply into the idiom, but not much. Both profitably could have studied the recorded legacy of the composer and his times: if they did. it didn't take, and one begins to wonder whether a generation reared on rock can learn to play the older jazz style with the necessary freedom and insight.

This collection has in its favor comprehensiveness and price: in addition, despite the multiplicity of listings in Schwann. there is very little around in up-to-date sound that doesn't have the same faults-or worse. Thus Siegel/Slatkin may not be ideal, but Leonard Bernstein is about the only one who can give them serious competition, and he has recorded only part of this material (American in Paris and the Rhapsody. on Columbia MS 6091 or M 31804). The Promenade, a most at tractive little work, does not seem to be other wise available, and any serious Gershwin admirer will want it. especially since this is one of the best performances in the set. Now that Gershwin by Gershwin is readily at hand. that is the place to begin, but Siegel and Slatkin are a sensible place to go next.

Technically. although the set is issued in QS (or RM ) quad. the four-channel playback with decoding is only slightly different from the simple. undecoded distribution of the material among four speakers. No big thrills here.

The orchestra and pianist are in the middle distance, the perspective of a balcony seat in a resonant hall. and a number of moments would have benefited from closer mike placement. But over-all the sound is pleasant. if un spectacular. and certainly adequate to put the performances across. -R.C.M.

HANDEL: Suites for Harpsichord (8). Colin Tilney, harpsichord. [Heinz Wildhagen, prod.] ARCHIV 2533 168 and 2533 169, $7.98 each.

2533168: No. 2, in F; No. 4, in E minor; No. 5, in E; No. 8. in F minor.

2533169: No. 1, in A; No. 3, in D minor; No. 6, in F sharp minor; No. 7, in G minor.

Comparisons:

Gould (Nos. 1-4) Col. M 31512 Hamilton (Nos. 3, 7) Delos 15322

After Glenn Gould's recording of the first four Handel harpsichord suites appeared in early 1973. I remarked that both the pieces and Gould's performances were of such high quality that they might well bring about a revival of interest in Handel's keyboard music. At that time the only recordings available of any of the suites were included as single items in collections of miscellaneous keyboard works. Of course whether the Gould recording has actually been responsible is impossible to say, but since then we have had offerings by Malcolm Hamilton of two suites and the G major Chaconne. and now this two-volume Archly release with Colin Tilney of all eight suites from the 1720 collection. (Ten additional suites were published later, in the 1730s.) Tilney, unlike Gould and Hamilton. per forms the pieces on baroque harpsichords: built by Christian Zell in 1728. and Nos. 2, 4, 5, and 8 on a single-manual instrument built by Johann Christoph Fleischer in 1710. His playing suits these older instruments, which are more limited in timbre (at least in respect to registrational possibilities), extremely well; he plays in an intimate, flexible manner that is nicely scaled to the possibilities of the me dium. I miss at times the more aggressive, ex citing approach of Gould and Hamilton. yet there is a charm to the simplicity of Tilney's readings that is most attractive.

I do wish, however, that he could have been more venturesome and inventive in matters of ornamentation. True, Tilney elaborates occa sionally, particularly on repeats. but always within an extremely confined range. Another minus, to my mind, is his love of notes inegales in places where steady sixteenths are indicated (e.g., in the Allemande of Suite No. 3); used judiciously, these dotted rhythms can provide a welcome means for enlivening the musical surface (and they were undoubtedly so employed by Handel's contemporaries), but when overdone the effect can become turgid and relentless.

These are relatively minor matters compared with the good points on these discs, both of which are warmly recommended. They confirm my earlier impression that these suites constitute some of the finest music in the baroque keyboard literature. And I suspect that we will be hearing them more and more often in coming years.

-R.P.M.

IVES: Music for Theater Orchestra. Yale Theater Orchestra, James Sinclair, cond. [ Lawrence Morton, prod.] COLUMBIA M 32969, $6.98. Quadriphonic: MQ 32969 (SQ-encoded disc), $7.98; MAO 32969 (0-8 cartridge), $7.98.

Charlie Rutlage; Chromatimelodtune; Country Band March; Evening; Fugue in Four Keys on "The Shining Shore"; Gyp the Blood or Hearst!? Which Is Worst?!: Holiday Quickstep; March II; March III; Mists; An Old Song De ranged; Overture and March "1776"; Remembrance; The Swimmers.

One of the many ways in which Ives broke with tradition, at least what we now think of as the nineteenth-century musical "establishment." was his use of small pickup groups of performers whose composition was deter mined mainly by the instruments that were at hand, rather than by some predefined ideal of ensemble sound. Ives referred to these ensembles as "theater orchestras." since theaters in those days always had some such band of players to supply music for their stage performances. As he once noted: "The makeup of the average theater orchestra ... depended somewhat on what players and instruments happened to be around. Its size would run from four or five to fifteen or twenty. and the four or five often had to do the job of twenty. . .." Ives's interest in these ensembles goes back at least as far as his Yale days in the 1890s. In this respect, as in so many others, his musical inclinations proved to be remarkably prophetic:

His better-known European contemporaries were to develop similar interests but only considerably later. Certainly one reason for Ives's use of these groups was purely practical. As a young. unknown composer devoted to musical experimentation, symphony orchestras were not available to him as a forum for his work. Theater orchestras, on the other hand, were commonplace in New Haven, as well as elsewhere; and for a small sum of money. or simply out of friendship, the players were usually willing to try out pieces for him. But this is only a partial explanation. Perhaps even more important was the fact that the kind of music Ives was interested in. music that-despite its manifold complexities-was deeply rooted in the popular music of his day, was eminently suited to these motley instrumental combinations.

Although many of the theater pieces have previously been recorded, this new Columbia release brings first recordings of fourteen compositions. at least in the versions offered here.

Ives left most of his scores in a decidedly disorganized state at the time of his death. and all of the present pieces have only recently been edited-by John Kirkpatrick. James Sinclair, and Kenneth Singleton-from material in the Ives Collection at Yale University. The sum is a wonderfully mixed bag of musical miniatures, ranging in date from the early 1890s to the 1920s and in character from parodies. such as the wonderful takeoff on country bands in the Country Band March. to such advanced musical experiments as the multi-tonal fugue on The Shining Shore and the serial intricacies of Chromatimelodtune.

This last piece now exists in three versions, each put together from Ives's own somewhat fragmentary sketches: this one by Kenneth Singleton. one by Gunther Schuller (recorded on Columbia MS 7318), and one by the American Brass Quintet (recorded on Nonesuch H 71222). Although the Schuller remains my favorite, Singleton's version, which is quite different. has its own appeal and is well worth hearing.

Indeed, those interested in Ives will want to have all of these pieces in their library, as they form an important and unique part of his out put. The performances by the Yale Theater Orchestra (made up entirely of students and former students of the Yale School of Music) under Sinclair's direction are remarkably professional, and the sound quality of the disc is excellent. Singleton supplies brief but helpful notes on all the compositions.

-R.P.M.

JOPLIN: Piano Works. Joshua Rifkin, piano. [Marc J. Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz, prod.] NONESUCH H 71305, $3.98.

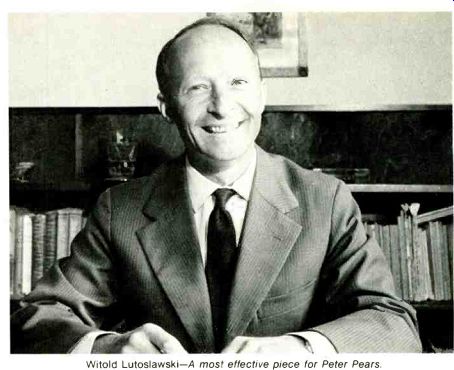

------------ Witold Lutoslawski-A most effective piece for Peter

Pears.

Original Rags; Weeping Willow; The Cascades; The Chrysanthemum; Sugar Cane; The Nonpareil; Country Club; Stoptime Rag.

B JOPLIN: "Complete" Works. Richard Zimmerman, piano. [Lee Palmer, prod.] MURRAY HILL 931079. $11.99 (five OS-encoded discs, manual sequence).

JOPLIN: Piano Works. Richard Zimmerman, piano. OLYMPIC 7116, $4.98 (OS-encoded disc).

A Picture of Her Face; Great Crush Collision: Maple Leaf Rag: Peacherine Rag; Sunflower Slow Drag. Augustan Club Waltz: The Entertainer: The Strenuous Life: Some thing Doing; The Favorite.

The long-awaited sequel to Joshua Rifkin's two previous Joplin records has brought me back from an extended leave of absence from the Joplin Boom (a leave that began some where between "Joplin for Harmonica Band" and "The Mormon Tabernacle Choir Sings Joplin"). Listening to the three discs together, along with Richard Zimmerman's set and some other recordings. only renews my admiration for Rifkin's accomplishment.

The new record has a predominantly reflective tone, but with ample relief in the exquisitely scintillating The Cascades (1904). the oddly whimsical Sugar Cane (1908). and the boisterous Stoptime Rag ( 1910). Filling out the collection are two sturdy, uncomplicated early works--Original Rags (1899. arranged by Charles N. Daniels) and Weeping Willow (1903): The Chrtsanthemum (1904). a lovely "Afro-American intermezzo" that complements The Cascades: and an intriguingly con trasted pair of later two-steps. The Nonpareil (1907) and Country Club (1909).

All receive Rifkin's familiar scrupulous musicianship. His heel-stamping in Stoptime is less successful. but at least it's there to under line the vacant beats. In Zimmerman's performance. even on the rests you can barely hear the stomps. (If it's stomping you want, try, Wm. Neil Roberts on Klavier KS 510: He clomps up a storm while his harpsichord tinkles in the background.) The Zimmerman set includes competent piano renditions of everything in the two-volume Collected Works plus the three rags that could not be published in Vol. I and two "lost" songs-"Lovin' Babe" and "Snoring Sampson"--that have turned up since Vol. 2 was published. In addition. Zimmerman has supplemented the three published piano excerpts from Treemonisha with his own seventeen-minute medley from the opera. Maple Leaf and Pine Apple are of course done only in the standard piano versions. but Ragtime Dance is done in the earlier. more elaborate song version. Everything is performed on solo piano.

The set is thus of considerable documentary value. abetted by an extensive booklet (a so-so background piece by Ian Whitcomb and elaborate. excellent, though often arguable notes on the music by Zimmerman himself) and the very low asking price for these ten well-filled. if not well-pressed, sides.

As for the performances, Zimmerman is earnest. He gets a rather clattery piano tone and employs a fair measure of rhythmic license. which some listeners will prefer to Rifkin's basically straight. sonorous approach.

But the more intricate Joplin's rhythms be come. the more dangerous such a style is. Listen. for example. to the gnarled second strain of Solace: Zimmerman completely loses the rhythmic sense of the first and fifth bars: Rifkin fits it all together very naturally in his Vol. 2. If rubato is to be used in this music (but why?). it requires enormous control-as in William Bolcom's Joplin recordings ( his So lace is on the New York Public Library's "Evening with Scott Joplin" disc).

Still, there's a lot of music here. much of it unavailable elsewhere. The Olympic disc is drawn from the Murray Hill set. Unless you happen to want this particular group of pieces.

I'd say the single disc is a red herring-the set should probably be a take-it-or-leave-it prop osition.

As for me. wake me when Rifkin's Vol. 4 comes along. ( Would you believe he still hasn't recorded Peacherine?)

-K.F.

LEONCAVALLO: I Pagliacci-See Verdi: Rigo lett() Liszy: Totentanz-See Franck: Symphonic Variations LUTOSLAWSKI: Paroles Tissees.

BERKELEY: Four Ronsard Sonnets.

BEDFORD: Tentacles of the Dark Nebula. Peter Pears, tenor; London Sinfonietta, Witold Lutoslawski, Lennox Berkeley, and David Bedford, cond. [James Mallinson, prod.]

HEAD LINE HEAD 3. $6.98 (distributed by London Records).

TAKEmitsu: Corona ( London version); For Away; Piano Distance; Undisturbed Rest.

Roger Woodward, keyboards. [James Mallin son, prod.] HEADLINE HEAD 4, $6.98.

These two discs are part of the initial release in Decca/London's new "Headline" series de voted to contemporary works. [HEAD 1/2, Messiaen's La Transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jesus Christ. is reviewed separately.] The works by Lutoslawski, Berkeley, and Bedford were all commissioned by Peter Pears, who sings them here. They also have in common the fact that each is scored for chamber orchestra (although specific instrumentation differs) and that in each the musical emphasis is placed almost entirely on the vocal line.

Strongest of the three is Lutoslawski's Pa roles Tissees (Woven Words), written in 1965 to texts by Jean-Francois Chabrun. Although the style is rather eclectic, the composer's sure hand and strong musical personality produce a convincing musical unity. The general character is understated, yet the assortment of techniques-particularly impressive is the virtuoso use of ostinatos and other types of recur rent musical figures-results in an extremely varied and attractive musical surface. A minor piece. perhaps. but one that is most effective.

Lennox Berkeley's Four Ronsard Sonnets, based on the sixteenth-century poet's Sonnets pour Helene and dating from 1963, is more conventional. Essentially tonal, it is very much in the sort of "pastoral" style so favored by British composers during the first half of this century. Like the Lutoslawski, it is well written for both voice and instruments, but here one is less conscious of an individual voice. The third piece. David Bedford's Tentacles of the Dark Nebula, is a melodramatic setting of a segment taken from Arthur C. Clarke's short story "Transcience." Actually, the text is sung. not spoken, but the vocal line is so closely tied to Clarke's prose that it seems to be little more than very subdued recitative. Since the string accompaniment is equally confined in expression, consisting mainly of evocative back ground effects with little musical interest of their own, the result is a bit tedious.

Pears sings all of these pieces quite beautifully. but the small orchestra, conducted in each case by the composer. is at times less se cure than it might be. An elaborate booklet containing notes on the pieces. pictures. and texts with translations is included.

The second disc is devoted entirely to key board music by Toru Takemitsu. He is probably Japan's most prominent contemporary composer (in addition to his concert work, he has been active as a film composer: e.g. Woman in the Dunes) and is clearly a musician of considerable talents. The strongest piece here is Corona. a lengthy work (it takes up a full side of the disc) in graphic notation writ ten in 1962. Corona features a brief, largely rhythmic motive that recurs intermittently throughout to punctuate first long silences and then sustained, gently pulsating organ harmonies. The latter provide a largely static background against which this motive. as well as other occasional moments of musical activity. are contrasted. There is a tendency for the level of activity to increase in the first part of the piece and then to relax toward the end, so that there is a distinct sense of shape to the overall process.

Since Corona is graphic and thus deter mined to a significant degree by the per former. particular credit should be given to pianist Roger Woodward. who uses several keyboard instruments in this version. which was put together by overdubbing. Woodward has obviously worked the piece out in advance with great care, and undoubtedly much of the character of the composition is due to his participation (which is acknowledged in the title's reference to "London Version"). He also plays the three purely pianistic works on the reverse side with considerable flair. All of these are basically studies in sonority, composed by Takemitsu with delicacy and skill.

Especially notable is Undisturbed Rest. the earliest of the pieces (1952). as it so clearly in dicates the influence of the Scriabin-Debussy Messiaen line of twentieth-century musical composition. This influence is still noticeable in the later Piano Distance (1961) and For Away (1973). but here it has been largely absorbed into Takemitsu's own very personal blend of Eastern and Western elements.

Again, a booklet with notes and pictures is provided. One small quibble: The notes state that in Corona Woodward has "combined the sound of three keyboard instruments, piano, harpsichord, and organ": but a celesta is also used, as well as some nonpitched percussion.

-R.P.M.

MARTINO: Notturno.

WUORINEN: Speculum Speculi. Speculum Musicae, Daniel Shulman (in the Martino) and Fred Sherry (in the Wuorinen), cond. [Marc J. Aubort and Joanna Nickrenz, prod.] NONESUCH H 71300, $3.98.

Speculum Musicae is among the most accomplished of the new-music groups in the New York area. It has also been active in seeking out new works for its repertoire. and both of these pieces by Donald Martino and Charles Wuorinen owe their genesis to commissions for the ensemble from the Walter W. Naumburg Foundation.

Martino's Notturno. which was awarded the Pulitzer Prize for Music in 1974. is arranged in a symmetrically organized sectional layout. al though this formal aspect is somewhat belied by the effective presentation of a larger. more fundamental continuity. The piece seems to have been composed in a single. uninterrupted breath. That it gives this impression de spite the presence of violent contrasts--particularly in regard to sustained notes as opposed to fragmentary bursts of events in variable speed- is a measure of the composer's achievement. Although complex. the work is extremely exciting. even on first listening: and its interest grows with greater familiarity.

Like Notturno, Wuorinen's Speculum Speculi (Mirror of the Mirror) was completed in 1973. It resembles the other composition in its sectional layout. although here the sections take the form of variations on a twelve-tone set that is first presented in isolation at the opening. The general tendency throughout the piece is one of increasing textural and rhythmic enrichment, although there seems to he a final dissolution of activity as the end is approached. Thus the sense of forward growth, or traditional musical "progress." is somewhat stronger than in the Martino: and the constant recurrences of the rhythmic and melodic contours of the basic material provide the work with a more immediately graspable formal shape.

The readings by the Speculum Musicae should serve as models for all groups performing new music. It is not just a matter of getting the right notes out at the right time (although this certainly has something to do with it): De spite the considerable difficulty of these new works, the group plays both compositions with a consistently high degree of nuance and a clear grasp of the essential musical argument.

The players are due congratulations for having brought to life-and here in a double sense. thanks to the commissionings-two such forceful examples of contemporary American music.

-R.P.M.

Mascagni: Cavalleria rusticana--See Verdi: Rgoletto

MESSIAEN: La Transfiguration de Notre Seigneur Jesus Christ. Westminster Choir;

National Symphony Orchestra, Antal Dorati, cond. HEADLINE HEAD 1 /2, $13.96 (two discs, automatic sequence; distributed by London Records).

I find it increasingly difficult to turn on to the musical sermonizing Messiaen seems to be indulging in with a passion these days. Time was when the composer's philosophic vision, which is of capital importance in sufficiently catholic to serve as a pretext for a highly elaborate, often exceedingly complex musical language that seemed to be reaching toward some sort of universal totality.

Recently. however, he seems to be narrowing his sights to embrace only what is Catholic, and the resultant musical language has a certain Jansenist quality that seems somewhat in conflict with the diverse Messiaen tics that keep popping up with a vengeance.

In the end, what is annoying about such works as the Meditations sur le nnstere de la Sainte Trinite for organ and the Transfiguration (1965-69) recorded here is not so much the music itself, which offers any number of gloriously beautiful and intensely moving moments, but the format in which it is presented. Both the Meditations and the Transfiguration were intended as series of meditations on various sacred texts that ( in the two parallel septenaries that make up La Transfiguration) are sung in Latin by the chorus, usually in unison and often giving the impression of an atonal Gregorian chant. By concentrating on certain key elements of the texts ( from the Bible, the Missal, and St. Thomas Aquinas. the latter supplying at least one passage-the one used in the ninth movement-that seems like pure catechism), the composer has been led to isolate the separate musical ideas, which succeed one another in a strongly linear progression. Even if you don't follow the texts (and I strongly recommend you don't), the obsessive appearance of what are obviously key musical symbols gives the impression of a kind of self-righteous smugness, if such a thing is possible on a purely musical level.

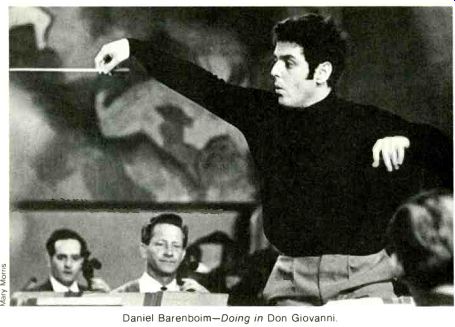

---------- Daniel Barenboim-Doing in Don Giovanni.

I hesitate. however, to sound so negative about a piece in which there are so many absolutely striking musical ideas. Among them are the rather Oriental opening motive, a descending figure played mostly on gongs of increasingly large size, the last one a real monster; some of the non-chant choral passages in which mysterious chordal configurations are set against equally strange harmonies in the brass: and the solo cello theme first heard in conjunction with the chorus and other solo instruments at the opening of the fifth movement and leading miraculously back into the women's voices at the end of the same movement.

The first release in Decca/ London's new "Headline" contemporary-music series, La Transfiguration receives a taut, intense, even impassioned performance by Dorati and the various instrumental forces involved. with Yvonne Loriod playing the piano part with her usual crisp precision. The Westminster Choir, on the other hand. could have used a great deal more rehearsal.

The recorded sound. both in its ambience and in its depth and clarity, highlights every facet of the composer's musical vision, which expresses itself unflinchingly from subtle pianissimos to some really whopping fortissimos in the percussion and brass.

-R.S.B.

Mozart: Don Giovanni. Don Giovanni, Donna Anna Commendatore Don Ottay.o Donna Elvira Leporello Zerlina Masetto Roger Soyer (be) Antigone Sgourda(s) Peter Lagger (be) Luigi Alva(t) Heather Harper (s) Geraint Evans(b) Helen Donath (s) Alberto Rinaldi (bs) Scottish Opera Chorus; English Chamber Orchestra, Daniel Barenboim, cond. [Suvi Raj Grubb, prod.] ANGEL SDL 3811, $27.98 (four discs, automatic sequence).

The present album commemorates a production of the opera given at the Edinburgh Festi val in September 1973 and repeated, with al most the same cast, in 1974. Since EMI announced its plans to record this Don Giovanni before the 1973 premiere, it presumably could not back out of its obligation there after-though one imagines that the Edinburgh reviews must have occasioned a certain amount of executive soul-searching.

Peter Ustinov's direction and designs earning universal disapproval and Daniel Barenboim's conducting faring scarcely better. With the former we are, happily, not concerned.

With the latter we unfortunately are.

One can see what Barenboim must have been after. The big. dark sound he has striven for, his strong attacks. the almost unrelieved solemnity of his approach-these bespeak a tragic view of the opera. After traversing Barenboim's weighty. not to say ponderous, account of Don Giovanni's career, and especially after witnessing the Don's painful, slow descent into hell, it comes as something of a shock to be confronted by lighthearted moralizing from the rest of the characters. Mozart's comic irony has no place in Barenboim's view of the opera.

Even so. one feels the strain of its suppression. A great deal of this performance is la bored. Leporello's account of his master's erotic triumphs is lugubrious enough to pass for a lament; "La ci darem" proceeds with caution, impelled less by ardor than by circumspection;

"Batti, batti" and "Vedrai, carino" meander sluggishly along: the finale of Act 1 is, given the dramatic circumstances, remarkably staid.

Some of Barenboim's tempos are. indeed, so eccentric as to induce confusion in the listener.

By the time Elvira has completed the opening phrases of the quartet ("Non ti fidar. o mis era") one is half mesmerized with anxiety, rather like waiting for the other shoe to drop.

There are several moments when one wonders whether the music is about to come to an end for example. in the recitativo accompagnato before "Or sai chi Vonore." when Don Ottavio expresses relief at learning of Anna's escape from the Don.

Though a few of the numbers are brisk-the opening of Act II, "E via buffone." is positively hectic-Barenboim favors deliberation. With this goes a predilection for thick textures and prominent woodwinds. To be fair to him, he does achieve some striking results. The massive overture. the entrance of Zerlina and Masetto into the buio loco, and a large part of the graveyard scene are masterful. But to be fair to Mozart. one must protest the conductor's willful misrepresentation of the music as a whole.

Appoggiaturas are haphazard. here one minute. gone the next. In one respect. how ever. Barenboim has played the purist. He has presented the original Prague version of the opera. "Dalla sua pace." "Mi track." and the Zerlina/Leporello duet are cut from the performance. though they are included at the end as a kind of recital-appendix.

The singing is not of a quality to make one overlook the conductor's quirkiness. Antigone Sgourda is. like the rest of the cast, conscientious. But she isn't really up to the rigors of Donna Anna's music, especially at the top of the staff. where the voice lacks control, and though she handles the fioritura at the end of "Non mi dir" better than a lot of Donna Annas (Nilsson. for instance) she doesn't really have the necessary authority. Heather Harper's Elvira is highly proficient, but the voice, to my ears, is rather chilling. She wants temperament. tonal variety, and better low notes. The delightful Helen Donath is the best of the women, though even she seems less poised than usual, and her high notes are not always properly focused. Only in the duet with Leporello does she sound entirely at ease.

Roger Soyer's Don is smoothly sung. The Serenade is handsomely done, the second verse in a very seductive mezza voce. Soyer, no doubt about it. is a very good singer. though I find him too phlegmatic to be entirely satisfactory in this role. Sir Geraint Evans' firmly characterized Leporello holds up well despite advancing years and some rather unidiomatic pronunciation. Luigi Alva's Ottavio. I am sorry to say. does not hold up. For all the tenor's grasp of style. his voice is now so be yond its prime as to be an embarrassment, above all in "Dalla sua pace." Barenboim does not help matters by taking the aria at a tempo so broad that only a Dame Clara Butt could have negotiated it successfully. Peter Lagger is a rough, hollow-voiced Commendatore. Alberto Rinaldi a convincing Masetto. The English Chamber Orchestra does with skill what Barenboim asks of it.

My recommendation to anyone in the market for a Don Giovanni is. first, to leave this one alone, and then to make for Colin Davis' ( Philips 6707 022) for all-round satisfactoriness, for Giulini's (Angel SDL 3605) for the conductor's glorious insights, and for Bonynge's (London OSA 1434) for eighteenth-century niceties like ornamentation and appoggiaturas. D.S.H.

NIELSEN: Symphonies.

PROKOFIEV: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra. No 2, In G minor, Op 16

TCHAI KOVSKY: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 1, in B flat minor, Op. 23. Tedd Joselson, piano; Philadelphia Orchestra, Eugene Ormandy, cond. [Max Wilcox (in the Prokofiev) and Jay Saks (in the Tchaikovsky), prod.]

RCA RED SEAL ARL 1-0751, $6.98.

Tedd Joselson is the young Belgian-born American pianist who made his debut with Ormandy and the Philadelphians last year. He does indeed seem a promising talent, with a large-sounding tone, a song-ful way of phrasing, and considerable coloristic ability. His somewhat romanticized Prokofiev concerto lacks the caustic bite and every-note-in-its-place poise of Jorge Bolet's old Cincinnati version, or of Kapell's account of the not dissimilar Third Concerto: it is. in fact, much akin to his treatment of the overside Tchaikovsky concerto. I am willing to overlook a few gaucheries. since Joselson offers so much else that is appealing and earnestly sincere. He should prove a persuasive recitalist, and I look for ward to hearing him in that role.

Unfortunately there are simply too many versions of the Tchaikovsky to give more than cursory notice to this slipshod, slackly con ducted newcomer. Ormandy sets good-rather brisk-tempos but squanders that advantage through stodgy. aimless phrasing. The orchestral execution is poor by Philadelphia (or any other) standards: The strings are messy; the woodwind scales in the finale are full of tiny, but noticeable, flubs. Moreover, the disc side is overcrowded, with resultant pre-echo. and the faulty microphone placement produces a flatulent ensemble tone full of muddy ambience.

Playing and engineering are altogether better in the Prokofiev but not perfect. The orchestral execution and balance, while still uninteresting and soft on detail, are at least reasonably compact. But the sound still doesn't seem quite properly equalized.

-H.G.

RAVEL: Sonatine; Le Tombeau de Couperin; Valses nobles et sentimentales. Pascal Roge piano. LONDON CS 6873, $6.98.

RAVEL: Piano Works. Abbey Simon, piano. Vox SVBX 5473, $10.98 (three discs, manual sequence).

RAVEL: Piano Works. Philippe Entre mont, piano'; Dennis Lee, piano (in Ma Mere l'Oye and Habanera). COLUMBIA D3M 33311, $13.98 (three discs, automatic sequence).

A Is manure de Borodino"; A la maniere de Chabrier"; Gaspard de la null"; Habanera': Jeux d'eau"; Ma Mire l'Oye'; Minuet antique"; Minuet sur Is nom de Haydn"; Miroire.: Pavane pour une Infants difunte"; Prelude; Sonatine"; Le Tombeau de Couperin"; La Vales*: Valses nobles et sentimentales".

The record companies' initial contributions to the Ravel centenary have centered on the pi ano music. The disc by the twenty-three-year-old French pianist Pascal Roge is the first of an apparently integral set. Philippe Entremont's album includes the standard solo and four-hand works plus the seldom recorded Habanera for two pianos, a piece later incorporated into the Rapsodie espagnole. The Abbey Simon set comprises all the published works for solo piano, including the piano version of La Valse, which the artist's virtuosity almost makes sound convincing in this format.

Although stereotyping might seem to favor the Frenchmen, Roge and Entremont, it is the American-born Simon who walks away with the honors here. It takes truly flawless, sure-fingered execution to communicate Ravel's often note-filled musical ideas, and Simon has always amazed me with the clarity of his pianistic articulation, even in the fastest, most difficult passages. Yet Entremont and Roge like wise show incredible suppleness and control in working their way through Ravel's evocative keyboard filigrees, whether in the quiet effervescence of Jeux d'eau or in the more slap dash Valses nobles et sentimentales. Indeed Roge gives promise of becoming a virtuoso's virtuoso.

What Simon adds to the music is a certain rather romantic sense of lyrical line. Even though Ravel set off in new directions, he was not entirely divorced from the more melodically oriented traditions that immediately pre ceded him, and, while some pianists-notably Samson Francois-lean back too heavily toward the nineteenth century in their Ravel interpretations, it is important to the cohesion of the music that the various themes and motives not be buried in the proliferation of notes.

This is pretty much the flaw in the Roge disc. While it is impossible not to admire the ease and absolute fluency of the pianist's fingerwork, there is a certain sameness in the sounds he produces. which dulls the incisiveness of the music's motivic structure and drains some of the life from the rhythmic language. particularly in Le Tombeau de Couperin. And as is typical of London piano record ings, the high notes have a frustratingly muted quality, even though the sound as a whole has both depth and richness. (The sound is not the problem. however: Roge's Gaspard de la nuit and Sonatine at his New York debut recital left much the same impression.) Entremont has different problems. Indeed, in certain pieces, such as the Pavane pour une infante defunte, one of Ravel's most poignantly lyrical works, his phrasing and subtly highlighted thematic lines create a per fect mood. And my enthusiasm would have been strong indeed if his efforts had been lim ited to the more understated works such as the Pavane, the two A 1a maniere de pieces. and the autumnal Sonatine, all on Side 1. which contains some of the best playing I have heard from Entremont.

But even in the above pieces, one can detect a certain hardness in tone and approach that has, for my money, always tended to mar the pianist's style. When Entremont comes to the bigger works, the Valses nobles et sentimen tales or Gaspard de la nuit, the relaxedness and flexibility that represented definite pluses in the simpler works largely disappear, so that the sheen of his articulation, the clarity of his melodic line, and the gracefulness of his rhythms all tend to be drowned in tonal over statement, which is a shame. Even in the low key quiescence of the morbid "Gibet" movement of Gaspard, his pounding of the repeated B flat quite unbalances the entire movement.

Columbia's sound, except for some excessive hiss, is outstanding, but there is some pretty grim pre- and post-echo on some of the sides.

The sonics-if not the surfaces-on the Vox Box are every bit as good as Columbia's, and Simon has come up with some of the finest Ravel playing I know of. (The Gaspard and Valses, by the way, are the same performances previously issued on Turnabout TV-S 34397.) While I might quarrel slightly with the hur riedness of the Sonatine's opening movement or with the somewhat mechanical approach to the Jeux d'eau. which could benefit from a bit more panache than Simon gives it, his lightness of approach and execution, his sense of movement and lilt. and his ability, in the midst of the often phenomenal difficulties, to communicate the underlying simplicity of the Ravelian universe make this Vox contribution the highlight to date among the centenary re leases.

-R.S.B.

Schubert Sonata for Arpeggione and Piano, in A minor, D. 821; Variations on "Trock'ne Blumen," for Flute and Piano, D. 802. Klaus Storck, arpeggione (in D. 821); Hans-Martin Linde, traverse flute (in D. 802); Alfons Kontarsky, hammerflugel. [Andreas Holschneider, prod.] ARCHIV 2533 175, $7.98.

It had to happen. At long last we have a performance of the Arpeggione Sonata on, of all things. the arpeggione! Schubert composed the work for the hybrid creation of Johann Georg Stauffer, a Viennese violin--and guitar-maker, but by the time the manuscript was re discovered and published in 1871 the arpeggione--or "guitarre d'amour," as Stauffer called it-had lost its brief vogue, and the sonata became part of the standard cello repertory. Violists. always rapacious for appropriable fare, have also claimed the piece, and I have heard performances on clarinet and contrabass.

So what does the original sound like? Well, for one thing, much easier for the performer.

The arpeggione, an instrument with six strings tuned to E, A, D, G, B. and E' and frets, re sembles a guitar in many respects but is bowed like a cello. Whereas the poor cellist (the poor good cellist, that is-"poor" cellists stay away from this treacherously difficult work!) must struggle in the high positions and hope for the best with regard to intonation, the lucky arpeggionist can take everything in first position and needn't fret (pun definitely intended) about playing out of tune. On the other hand, the basically pleasant-toned arpeggione does sound rather archaic without vibrato, and of course the music loses the graceful, tensile quality so familiar from good cello or viola performances.

The performance by Storck and Kontarsky (who naturally plays on an authentic wooden-framed hammer-flilgel of the period) is well prepared but a bit on the dry. musicological side, and one wishes that the keyboard instrument were balanced more discreetly-it sounds too relentless and dominant.

Actually, the Trock'ne Blumen Variations are better served by authenticity. The traverse flute differs very little from the standard conical flute, but since it is made of ebony with ivory mounts it tends to produce a tone of piercing sweetness and succulence. I like the performance very much-obviously less powerful and dramatic than the incomparably temperamental one by Paula Robison and Rudolf Serkin (using modern instruments) on Marlboro Society MRS 3, but nonetheless pointed and stylish. The final alla marcia is done with particularly good effect, being neither prissy nor overdriven.

Aside from the noted balance problem in the sonata, the recorded sound is luminous and beautifully processed. The trilingual annotations are thoroughgoing in the familiar manner of Archiv Produktion releases. This is an exceptionally intriguing disc.

-H.G.

SCHUBERT: Fantasy, D. 760 (Wanderer); Sonata for Piano, in A minor, D. 784; Waltzes, D. 145-See Franck: Symphonic Variations.

TAKEMITSU: Keyboard Works-See Lutoslawski: Paroles Tissees.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Concerto for Piano and Or chestra, No. 1-See Prokofiev: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 2.

TCHAIKOVSKY: Concerto for Piano and Orchestra, No. 1-See Franck: Symphonic Variations.

Tippett: Concerto for Orchestra; Four Ritual Dances from "The Midsummer Marriage." London Symphony Orchestra (in the Concerto), Orchestra of the Royal Opera House, Covent Garden (in the Dances), Colin Davis, cond. PHILIPS 6580 093, $7.98 [Dances: from 6703 027, 1971].

Tippett Sonatas for Piano (3). Paul Crossley, piano. PHILIPS 6500 534, $7.98.

The importance of Michael Tippett is becoming increasingly more apparent in this country, and the present recordings make available works that we profit from knowing and are un likely to hear in our own concert halls with any frequency.

The dances from The Midsummer Marriage derive from Philips' complete edition of the opera; hence it is relevant to note that in that album Tippett observes that the performance follows the practices of the theater and that there is a cut "for choreographic reasons" in the first three dances as they appear in Act II.

The music is symphonic in spirit and sub stance, far above the usual run of operatic bal let pieces, and is an ideal introduction to Tippett's most widely known theater score.

The Concerto for Orchestra, now a dozen years old, is a large-scale example of the composer's skill in dealing with sizable instrumental forces. The first movement begins with small groups of players who eventually join together in what Tippett calls "jam sessions" although there is, in fact, little relation to jazz in what they play. The strings appear in the second movement and, indeed, dominate it, and then the entire ensemble is brought together in a rather formal finale employing canon and rondo devices. It's an attractive work, well worth discovery, especially in a performance as thoroughly sympathetic as Colin Davis'. (The Concerto recording dates back a number of years but now appears here apparently for the first time.) Tippett writes in his notes to the sonata collection that "part of the pleasure of writing for the solo keyboard is the sense of one per former producing all the necessary sounds," and this is piano music, clearly of today, yet clearly accessible to large numbers of listeners and clearly a product of the musical main stream that gave us the piano music of Beethoven and Brahms. It would be delightful if the Fifty-seventh Street managements discovered this repertory and those of us who review piano recitals with frequency heard more Tippett and less Prokofiev. The three sonatas, from 1938, 1962, and 1973, are representative of thirty-five years of Tippett's work and at once are indicative of his musical development and a reaffirmation of his basic consistency as an artist.

The performances are excellent, and the music becomes increasingly attractive with each rehearing. For those with an exploratory turn of mind, this is a record to be recommended.

-R.C.M.

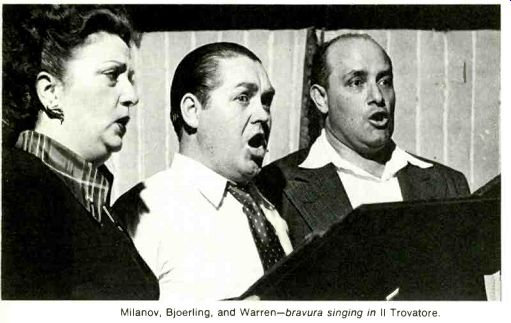

--------------- Milanov, Bjoerling, and Warren-bravura singing

in II Trovatore.

Verdi: Rigoletto. Rigoletto Gilds The Duke Sparalucile Count Monterone Maddalena Giovanna Borsa Marullo; Herald Count Ceprano Leonard Warren (b) Erna Berger (s) Jan Peerce (t) Itelo Tajo (bs) Richard Wentworth (bs) Nan Merriman (ms) Mary Kreste (ms) Nathaniel Sprinzena (t) Arthur Newman Paul Ukena (be) Countess Ceprano; Page Joyce White s) Robert Shaw Chorale; RCA Victor Orches tra, Renato Cellini, cond. [Richard Mohr, prod.] RCA VICTROLA AVM 2-0698, $6.98 (two discs, mono, automatic sequence) [from RCA VICTOR LM 6101 i LM 6021, re corded March-May 1950].

Bizet: Carmen. Carmen Micaela Frasquita Mercedes Don Jose Escamillo El Dancaire El Remendado Morales Zuniga Rise Stevens (ms) Licia Albanese (s) Paula Lenchner (s) Margaret Roggero (ms) Jan Peerce(t) Robert Merrill (b) George Cehanovsky (b) Alessio de Paolis(t) Hugh Thompson Osie Hawkins (bs) Robert Shaw Chorale; RCA Victor Orches tra, Fritz Reiner, cond. [Richard Mohr, prod.] RCA VICTROLA AVM 3-0670, $10.47 (three discs, mono, automatic sequence) [from RCA VICTOR LM 6012, recorded May-June 1951].

VERDI: Il Trovatore. Leonora Zinka Milanov (s) Azucena Fedora Barbieri (ms) R Inez Manna) Count di Luna Ferrando Ruiz Gypsy Messenger Margaret Roggero (ms) Jussi Bjoerling (1) Leonard Warren (b) Nicola Moscone (bs) Paul Franke (t) George Cehanovsky (b) Nathaniel Sprinzena (t); Robert Shaw Chorale; RCA Victor Orchestra, Renato Cellini, cond [Richard Mohr, prod ] RCA VICTROLA AVM 2-0699, $6.98 (two discs, mono, automatic sequence) [from RCA VICTOR LM 6008, recorded May 1952].

Mascagni: Cavalleria rusticana. Santuzza Margaret Harshaw (S); Lola Mildred Miller (MS); Mamma Lucia Thelma Votipka (a) Turiddu Richard Tucker (t) Ali* Frank Guarrera(b)

LEONCAVALLO: I Pagliacci. Nedda Canso Beppe Tonio; Silvio Lucine Amara (s) Richard Tucker (t) Thomas Hayward (t) Giuseppe Valdengo (b) Clifford Harvuot (b); Metropolitan Opera Chorus and Orchestra, Fausto Cleva, cond. ODYSSEY Y3 33122, $10.47 (three discs, mono, automatic sequence) [from COLUMBIA SL 123 and SL 113, recorded 1953 and 1951].

In 1950, after years of importing complete op eras from its European affiliates, RCA Victor undertook its first program of domestic operatic recording, perhaps feeling the competition (at least in terms of prestige) from Columbia's Metropolitan Opera series. The first three of these projects, having remained in the catalogue through thick and thin for over twenty years. are now transferred to the Victrola label. They are all famous recordings, and will hardly require much introduction to seasoned collectors; despite tangible limitations, they pretty well wipe out the none-too-impressive bargain-price competition. Per haps more significant, particularly to those who look to budget labels to supplement their basic opera collections with a variety of interpretations, certain individual performances in the Victor series are likely to be worth hearing as long as records are around.

With regard to the Rigoletto, the first of the series, I would single out Erna Berger's Gilda as the memorable performance. She comes by the appropriate virginal sound quite naturally, and fills out the character with genuine feeling: Gilda's innocence, spontaneity, affection, and intelligence are all made manifest in this lovely, oh-so-musical interpretation. Nan Merriman, too, is a very specific Maddalena, not some anonymous throaty whore of Mantua.

Leonard Warren's sound is certainly splendid, and basically right for the title role, but on this occasion often unvaried, and deployed with excessive rhythmic freedom, so that his first monologue, for example, degenerates into a series of divergent gestures. Part of the fault here and elsewhere must be laid at the feet of conductor Renato Cellini, whose reading is pretty generalized to start with and succumbs too easily and often to Warren's pulling and hauling. Cellini can't be blamed, however, when Jan Peerce gets the accents wrong in his canzona (it should be "La donna e mobile," not "La donnae mobile"), for the orchestra did it right first. But somebody with real authority would have enforced this and many other matters, notably in the area of dynamics--somebody such as Arturo Toscanini. who made both Peerce and Warren deliver more accurate (and more theatrical) performances in his 1944 concert version of the final act (RCA Victrola VICS 1314. rechanneled).

The secondary singers are an undistinguished lot; the choppy Monterone and cavernous Sparafucile don't help at all. On the plus side (as in all these sets) is Shaw's lively, well-disciplined chorus. This first recording of the series is uneven in sound and various in perspective-often much too close up, so that the Rigoletto/Sparafucile duet loses all the atmosphere Verdi so carefully scored into it.

Around the middle of Act II in this reissue. I began to notice some curious minor effects of fading. as if someone had decided to put into the circuit a gate-effect filter but adjusted it wrongly, so that lots of notes seem to be choked off just a smidgeon prematurely-so hang on to your old Victor pressings. All the standard opera-house cuts are made.

The second project was built around a forthcoming new Met production of Carmen starring Rise Stevens and conducted by Fritz Reiner-both of them recent RCA acquisitions; Bjoerling was originally announced as the Jose, but for some reason he opted out (his Met season that year ended in January. and perhaps he elected not to return to America for the recording) and Peerce, who never sang the part at the Met, replaced him. This is Reiner's only commercial recording of a complete opera, a distinction 1 count as its primary value: The playing is superbly disciplined, beautifully tailored and balanced, the pacing always apt and lively, with much attention to rhythmic niceties in all departments.