by David Hamilton

The Unanswered Question: Why?

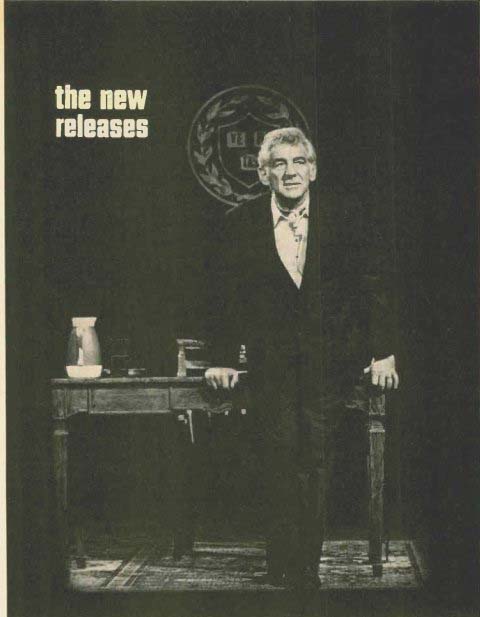

Columbia issues Leonard Bernstein's Harvard lectures on seventeen discs, and our reviewer is not impressed.

PERHAPS THE FOLKS down at Columbia Records know the old saying that "you can always tell a Harvard man but you can't tell him much." Still, somebody should have put it strongly to Leonard Bernstein '39 (as he is cozily embraced by Alma Mater in the liner notes, extracted from the Harvard University Gazelle) that plastering his Charles Eliot Norton lectures onto seventeen LPs would yield something of a white elephant economically, intellectually, and musically. Maybe some one did put it strongly, and to no avail. At any rate, here is the disc version of those lectures, doubtless to be followed in carefully timed succession by the TV syndication, the videocassettes, and perhaps even the book.

Harvard has few distinctions to bestow as prestigious as the Charles Eliot Norton Lectureship in Poetry, which since the academic year 1939-40 has been offered on several occasions to composers-the first of them Igor Stravinsky, whose lectures were published as Poetics of Music. Similarly slim, pithy, and polished volumes have followed from Aaron Copland (Music and Imagination), Paul Hindemith (A Composer's World). Carlos Chavez (Musical Thought), and Roger Sessions (Questions About Music), all dealing with fundamental questions of the art and craft of music: they belong in every music lover's library.

Should The Unanswered Question ever be boiled down to black type on white paper, it may conceivably belong on that same shelf-but the process won't be easy, for these records present such a muddle of intellectual pre tension, factual oversimplification, conceptual confusion, special pleading, bumptious hyperbole. specious argumentation, and sentimental Weltschmerz that the Linotype machines of the Harvard University Press might well refuse to cast it into type. Along the way, there are some genuine insights, and when L.B. sits down at the piano to explain the musical logic of. say, the opening of Beethoven's Sixth Symphony he is at his Young-People's-Concert best: lucid, engaging, and very much to the point (barring some curious terminology that his primary thesis saddles him with). This material, too, is the part of the lectures that endures validly on records-it would, indeed, be vastly less effective in a book, where music type would be a poor replacement for the audible examples. But it occupies only a fraction of these thirty-four long sides.

The "unanswered question" of Bernstein's title is "Whither music?" (He frequently refers to it as "Charles Ives's unanswered question," thus foisting on that un likely gentleman his own teleological preoccupations.) To answer this, he says, we must first ask "Whence mu sic?" and so we are soon deep in the genetic fallacy--i.e., the idea that to understand the nature of a thing one should study its origins. From here we move to a second primary thread, the attempt to divine a "worldwide grammar of music" along the lines of Noam Chomsky's structural linguistics, and this, padded out with a good deal of tedious speculation, leads, if I understand it, to the following questionable syllogism:

All languages share certain universals.

Music is heightened language.

Therefore music, too, is universal.

I wonder what they would say about that over in the Philosophy Department.

And I wonder what they would say in the Physics Department if you took them a record of Mozart's G minor Symphony and told them that all the notes in it came from the harmonic series-a few careful measurements would show that the notes in actual use could not be de rived from the harmonic series. This is Bernstein's next major line of discourse, and one that endures to the end:

The harmonic series is God's Truth in music, and the triad is Holy Writ (although he admits that the triad is a universal only in Western music, which tends to put a crimp in its "natural" primacy). By the end of the last lecture he is referring to the chromatic scale as "the twelve tones that nature gave us in the first place," al though no amount of juggling can make the harmonic series yield the equally tempered chromatic scale. This is the kind of slippery misrepresentation that goes on throughout the lectures.

The question is a large and complex one, and Bernstein has run up against the same obstacle that faces everyone seeking to put down recent non-tonal music on the grounds that it "denies" the harmonic series: To do so strictly requires you also to throw out most of the nineteenth century and even more-and nobody wants to do that. So Bernstein scuttles round the obstacle and pretends that it doesn't exist. (At another level, his "explanation" of the harmonic series and the triad is disappointing, simply as exposition; the important assumption of octave equivalence is not explained, nor the terms "tonic" and "dominant," which just dun up.) As far as the Chomskian structuralism is concerned, one would like to see Bernstein's presentation on paper; short of employing a professional courtroom clerk to transcribe several entire lectures, one has a hard time cross-checking statements at one point against those at another. Briefly, what he does is give a superficial presentation of Chomsky's models and then attempt to find analogies in musical discourse for their elements, rather than to examine musical practices for their own implicit structural logic. At times, he suggests that the real purpose of this structuralism-by-analogy is not intellectual, but explicatory: Through the use of language terminology rather than music terminology, the lay listener can be made to perceive musical process more easily.

But all of this is so sloppy. After setting up one chart showing a musical phrase as equivalent to a word in language, he shifts to a scheme where a motive functions like a substantive noun-and then illustrates it with a musical example in which a single note substitutes for a proper noun. At this point, my notes read "pointless parlor games"; in fact, it is a kind of show-off act, for Bern stein can do all manner of cute tricks at the piano (a chromatic version of "Fair Harvard," for example) to distract you while he slides over a tricky problem.

Somewhere along about the fourth lecture, we sidle into a capsule history of musical development in the nineteenth century in which perceptive analyses and demonstrations embellish an extremely conventional music-appreciation view of history (although the Bernsteinian hyperbole would embarrass even the most extravagant stylists of that genre: "gloriously mad Schumann," Stravinsky's Danse sacrale is "the supreme brutality of all time," and so on). And when the twentieth century heaves into sight, we encounter the final thread of argument-or, rather, pick up an earlier one in a new context. Chomskian linguistics have been left behind, save for the frequent use of the term "metaphor" to cover a variety of phenomena and relationships for which the musical profession has always had perfectly good, precise names. Instead we get confusion and error (Schoenberg's Brahms orchestration is not later than the G minor Band Variations, and the clear if un stated implication that Berg's Wozzeck is a twelve-tone work is quite misleading), a facile and unclear explanation of the twelve-tone method (which, of course, Berg "humanized" by the infusion of tonal triads), and a miasma of maudlin pessimism in re Mahler.

After Bernstein's perceptive and illuminating discourse on Debussy's Faune, I rather looked forward to his doing the same for the Adagio movement of Mahler's Ninth-but instead of analysis, we get "philosophy":

"Ours is the century of death, and Mahler is its musical prophet." We are now in the realm of the unverifiable, and my innate empiricism restrains me from arguing about such matters, even with the Norton lecturer; conceivably there are people who like this sort of thing, in which case this is the sort of thing they like.

Bernstein is so obviously earnest in his presentation, often so charming in manner and so virtuosic in his illustrations, and (obviously) a figure of such prominence in the musical world that many people may be tempted to regard his obiter dicta as automatically valid. But it's clear enough from these lectures that he's not a systematic philosopher, not a structural linguist, not a historian, not even a sound musical theoretician. He is an enormously gifted practical musician and composer who is unhappy about certain developments of the past fifty years and is trying to exorcise his agony by constructing a world view in which Schoenberg has to be "down" and Stravinsky (neoclassic Stravinsky, that is) has to be "up." From that point of view these lectures have considerable autobiographical significance, for they show Bernstein still fighting the aesthetic battles of his undergraduate days rather than seeking a fresh perspective.

What I do regret about this set is the good examples of Bernstein as teacher that are buried within. Perhaps Columbia will sit him down in a studio with the score of Beethoven's Sixth-or anything else-and ask him to spill all he knows. Many listeners, I believe, would find this of enormous value, sharpening their ears and increasing their pleasure. It would spare us, too, the really abysmal sound quality of the present records, which (except for the dubbed-in orchestral excerpts) seem to be taken from a low-quality TV soundtrack, with only a throat mike for pickup. The piano sound shatters at the least provocation, and we are treated to an unedifying assortment of grunts and groans from the pianist that out Glenns Gould by a wide margin. Somebody should be ashamed of this technical work.

Most of the albums include complete performances of the pieces discussed. Stravinsky's Oedipus Rex, in Vol. 6. is a new recording, a slightly soft-edged performance in which the Boston-based soloists (the Shepherd and the Messenger) walk off with the vocal honors. Space limitations forbid detailed consideration here, but it will likely be out as a single before long; it surely isn't so good that you should buy the four-disc album to get it.

In addition to the capsule accounts of each lecture on the back liners of the non-hinged album boxes, Columbia provides the graphs, charts, music examples, etc., that presumably were projected on a screen at the lectures themselves, along with a few lines of the spoken text (rather poorly edited and punctuated). If I were you, I'd wait for the book; paper prices are going up, but not so much that it will cost as much as $80. And in the mean time you may be able to catch this show free on TV.

BERNSTEIN AT HARVARD: The Unanswered Question (Norton Lectures 1973). Leonard Bernstein, lecturer; New York Phil harmonic (except as noted), Leonard Bernstein, cond. COLUMBIA, Six vols., various prices.

Vol. 1: Musical Phonology. Includes Mourn Symphony No. 40, in G minor. K. 550 [from MS 7029]. M2X 33014, $10.98 (two discs).

Vol. 2: Musical Syntax. M2X 33017. $10.98 (two discs).

Vol. 3: Musical Semantics. Includes Baernoviii: Symphony No. 6. in F. Op. 68 (Pastoral) [from MS 6549]. M3X 33020. $13.98 (three discs).

Vol. 4: The Delights and Dangers of Ambiguity. Includes Barnum Rom6o et Juliette--Part II [from MS 6170]; DIMIUSSY: Prelude a "L'Apres-midi d'un faune-[from MS 6271]; Tristan and Isolde: Prelude and Liebestod (from M 31011 and MS 7141]. M3X 33024, $13.98 (three discs).

Vol. 5: The Twentieth-Century Crisis. Includes Ives: The Unanswered Question [from MS 6843]. MANUA: Symphony No. 9, in 0: Adagio [from M3S 776]; RAWL: Rapsodie espagnole: Feria [from MS 6011]. M3X 33028, 813.98 (three discs).

Vol. 6: The Poetry of Earth. Includes Stravinsky: Oedipus Rex-Tatiana Troy anos (ms), Jocasta; Rene Kollo (t). Oedipus; Frank Hoffmeister (t), Shepherd; Tom Krause (b). Creon; David Evitts (b), Messenger; Ezio Flegello (bs). Tiresias; Harvard Glee Club; Boston Symphony Orchestra [John McClure, prod.; not previously released]. M4X 33032. $18.98 (four discs).

-------------

(High Fidelity, Apr. 1975)

Also see:

Link | --Link | -- The Complete Nielsen Symphonies (review, HF mag Apr. 1975)

Part II: Ravel On Records (Apr. 1975)