The New Releases:

Weber's Euryanthe: by Paul Henry Lang. Angel's recording rescues a musically startling but un-stageable opera;

The Conductor as Star: by Harris Goldsmith. Casals' Beethoven and Karajan's Berlioz dominate the field;

The Fourth Opera, by Andrew Porter, Not one, but two versions of Gagliano's La Dafne (1608).

-----------------

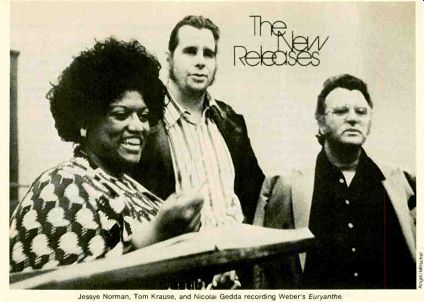

------ Jessye Norman, Tom Krause, and Nicola' Gedda recording

Weber's

Euryanthe Weber's Euryanthe: A Phonographic Treasure-Trove

Angel's premiere recording allows a close-up view of an opera unfit for the stage but startling in musical power and scope.

by Paul Henry Lang

FROM THE MAGNIFICENTLY sweeping overture on ward, this music continually fascinates. Euryanthe is strong and attractive in invention, bold in harmony; the orchestral writing is utterly original, colorful, and advanced to the point of being prophetic; the arias, more properly scenas, are beautiful, the choruses rousing.

The opera also shows the beginning of the use of the leitmotiv and the first signs of the eventual transfer of the point of gravity from the singers to the orchestra. Indeed, this opera exerted a profound in fluence on most German composers for the better part of the nineteenth century. Neither Tannhouser nor Lohengrin is imaginable without it; Lysiart and Eglantine are clearly the prototypes of the villainous Telramund and Ortrud, and Euryanthe is Elsa's model. Impressions from Euryanthe remained vivid in Wagner's mind all the way to Tristan.

It is well known what tremendous success Der Freischutz had in 1821, two years before Euryanthe--fifty performances in one year in Berlin alone. It instantly realized the century-old dream of a true Ger man opera, and the Italian operatic bastions in Germany began to topple one after the other. To be sure, one could point to three notable German operas that preceded Der Freischiitz, but The Magic Flute and Fidelio were great achievements of a personal nature, whereas Der FreischUtz, beyond that, suddenly fulfilled all that was dear to the German heart and became national property. The third predecessor, E. T. A. Hoffmann's Undine (1816), was actually called a romantic opera, but this engaging poet/novelist/conductor simply did not have enough musical talent to open new paths, though his opera was successful. By uniting the two streams of the era, the romantic and the national, Weber made the decisive step toward the creation of German romantic opera.

One would expect that Euryanthe, with its rich and admirable music, would have been even more acclaimed than Freischutz, yet, except for a few discerning musicians, it was a failure: People even referred to it as " Euryanthe." Many attempts have been made at salvaging this fine music, including re written or altogether new librettos accommodated to the music, and from Mahler to Tovey a number of versatile persons tried their hands at it. But nothing would work; Euryanthe simply won't hold the boards.

Now surely this is a puzzling situation. Not only was Weber an accomplished and highly successful composer, with a pronounced dramatic talent, but he was with Spontini the most experienced opera conductor of the age. He lived his entire life, from early childhood onward, in an operatic milieu, his father having run an itinerant opera company, and since the whole family was involved the child undoubtedly sang such roles as one of the boys in The Magic Flute. At the age of eighteen he was already conductor at the theater in Breslau and had several youthful operas to his credit. Rising in importance, he was en gaged by the German opera in Prague, famous as the birthplace of Don Giovanni, and at thirty he went to the royal opera in Dresden to organize the newly created German wing.

Weber's painstakingly prepared performances made history, because here for the first time was a man of the lyric theater who demanded not only good musical performance, but equally competent acting, as well as appropriate staging and decor. And he knew and conducted a very large repertory, from Singspiel and opera comique to the great works of Gluck, Mozart, Beethoven, Spontini, Cherubini, Spohr, Mehul, and Rossini. If we take an eminently successful composer, such as Donizetti, we shall find nowhere in his serious operas anything that even faintly approaches the strength, invention, and origi nality of such scenes as that of Lysiart opening the second act in Euryanthe or Euryanthe's scene with chorus in Act III. So how could Weber have failed so irrevocably? The immediately obvious shortcoming is the libretto, perhaps the most inept concoction in all opera-and Weber himself was largely responsible for this debacle. Though a highly cultivated man of let ters and a better critic than either Schumann or Berlioz, it was he who persuaded Helmina von Chezy, an amateur translator/poetaster, to write the libretto, despite her protestations that she knew nothing about the theater, let alone opera.

In addition, there were too many cooks at work on this unsavory brew. Various friends were consulted, among them Ludwig Tieck, the poet, dramatist, critic, and Shakespearean student, one of the leaders of the early German romantic school, yet the situation steadily worsened. The medieval tale (which Chezy had translated for an anthology) was simple enough; it served Shakespeare well in Cymbeline, but it was freighted-at Weber's insistence--with supernatural elements (which had worked so well in Freischutz), giving the plot a twist that made it both implausible and obscure.

But aren't there a number of great operas com posed on wretched librettos (as well as poor ones set ting excellent books)? There must be something in addition to the text that thwarted Euryanthe, and regretfully we must conclude that the score, despite all its virtues, must share the blame to a considerable degree.

Euryanthe was an ambitious plan. Stung by some criticism from the Spontini camp, Weber wanted to prove that he could go beyond the Singspiel and create a L :ma fide through-composed opera without self-contained "numbers" and without spoken dialogue; Euryanthe was to be a "romantic grand op era." Moreover, Weber clearly indicated that in this work "all the sister arts collaborate"--here is the blueprint for Wagner's Gesamtkunstwerk! According to the plan, there are no fully closed arias, as there were in Der Freischutz and all of eighteenth-century opera. Weber made the most of this freedom, composing scenes that are distinguished as drama, as character portrayal, and as mood pieces; secco, accompagnato, and arioso merge into a flexible fabric, a remarkable preparation for Wagner's "endless melody." There are long stretches of pure top-notch opera, and the second-act finale challenges some of the greatest masterpieces of the genre.

However, the Singspiel-like choruses and other folk elements, the extended dances, the long and elaborate ritornels, and the supernatural scenes are clearly inserts in an otherwise truly operatic texture.

They are not natural ingredients, as in Freischiitz, and the two diametrically opposed styles constantly clash. Mozart, too, made this error in The Abduction, mixing highly developed operatic ensembles and coloratura arias with popular Singspiel material. But then, he was Mozart; even his flawed work turned into a masterpiece, and by the time he finished The Magic Flute he had the blend miraculously right.

As one listens to this excellent recording, the first individual protagonist appears on Side 2; the whole of the first side is given over to the overture, choruses, and dances--all of them thoroughly enjoyable, but hardly operatic. The stylistic discrepancy is especially evident in the handsome choral numbers.

Some are the cherry-cheeked choral songs of the Singspiel, but others are starkly dramatic, forming an integral part of the action; the sequence can be distracting. The huntsmen's chorus following Euryanthe's infinitely sad cavatina, in which she prays for deliverance by death, is almost shocking. In sum, this rich and most influential work does not achieve a unified whole, and this failure, together with its hapless libretto, prevents it from regaining the stage.

But this comely music should not be lost, and all of us must be grateful to Angel for giving us such a splendid recording.

First of all, we should commend Marek Janowski, who conducts with bracing élan and sharp rhythm; the ensemble is faultless, the dynamic nuance refined, and the flexibility of the dramatic pace superb.

The uniformly intelligent and musicianly phrasing of the entire cast must also be credited to him.

The star of the international cast is soprano Jessye Norman. She has a beautiful and well-equalized voice; she can float exquisite pianos as well as dominate the assembled forces with a soaring and ringing treble. And this American girl enunciates German like a native. Rita Hunter has the fierce temperament needed for the role of the malevolent Eglantine, but when agitated she tends to lose her usual vocal composure and become edgy.

Nicolai Gedda is the fine musician of old, singing admirably at moderate dynamic levels, but the high and loud tones are becoming increasingly difficult for him, and he resorts to pushing his voice. Tom Krause is excellent in the sinister role of Lysiart and dominates the stage for long stretches. All the small roles are well sung by capable singers. Chorus and orchestra are first-class, and so is the engineering, save for a bit of echo fore and aft.

All in all, this is a recording to treasure. Angel includes sensible notes by John Warrack and the complete libretto in German and (good!) English.

Weber: Euryanthe.

Euryanthe Jessye Norman (s)

Eglantine Rita Hunter (s)

Bertha Renate Krahmer (s)

Aciolar A Krught Lysiart

The King NIC0181 Gedda (t)

Harald Neularch (t)

Tom Krause (b)

Siegfried Vogel (bs)

Leipzig Radio Chorus; Staatskapelle Dresden, Marek Janowski, cond. [David Mobley, prod.] ANGEL SDL 3764, $27.98 (four SQ-encoded discs, automatic sequence).

In quad: EMI/Angel has resisted the temptation that (I assume) must have existed to turn this recording into a quadriphonic spectacular. Euryanthe has no stunningly "spatial" counterpart to the Wolf's Glen scene in Freischiltz nor the storm in Oberon, but it does have big court scenes-they both begin and end the opera-full of fairly complex confrontations.

(Again, one is reminded of Lohengrin.) An all-out quad production might have isolated the contrasting sentiments all about the listener, and in the process it might have become so gimmicky as to be distracting unless it were superbly handled.

By contrast, the SQ treatment achieved is discretion itself. The overture is given some wraparound quality, but once the curtain is up, so to speak, the treatment is consistently proscenium-plus-ambience. Perhaps the most tellingly "quadriphonic" passage occurs in the desert scene in Act III. Euryanthe sings her cavatina ("Hier dicht am Quell"), appropriately, before the footlights. As dawn breaks, the horns that introduce the huntsmen's chorus are heard in the distance from the right back, with their echo (that is, the echo responses written into the score-not some sort of phony reverberation) shimmering from left front. During the chorus, horns and singers alike make their way on-stage from the right to discover Euryanthe.

This might profitably have been carried a little further, I think. The wedding cortege that provides the setting for Eglantine's final entrance, for example, seems curiously static. Only the change in ambience, in comparison with the pit-orchestra accompaniment that precedes it, suggests (very effectively) that the wind players are walking on-stage. When Eglantine breaks madly away from the procession, we have only Weber's scoring to suggest the stage picture. The passage seems to call for a bit more audible motion.

ROBERT LONG

------------

Two Instant Classics in the Symphonic Discography

ROBERT LONG by Harris Goldsmith

Herbert von Karajan ; Pablo Casals

Casals' newly issued Beethoven Seventh (Columbia) and Karajan's new Symphonie fantastique (DG) dominate the modern competition.

THIS IS THE ERA of the conductor as "personality," which perhaps explains why this is also the era of the "instant conductor"--all those instrumentalists and singers picking up batons surely know a good thing when they see it.

And yet the number of truly distinguished conductors is depressingly small, as each month's batch of releases reminds us. So it is an uncommon pleasure to welcome new versions of two often-recorded sym phonies that take their place at the top of the modern lists: Columbia's posthumous issue of Pablo Casals' Beethoven Seventh and DC's new Karajan recording of the Berlioz Symphonie fantastique.

If Casals' place in musical history as the man who practically invented the cello has overshadowed his stature as a conductor, one can hardly accuse Columbia of overlooking that aspect of his career: It re corded him regularly in that capacity from 1950 on ward, and the current catalogue is rich with his interpretations. As I noted in reviewing Columbia's "Homage to Casals" box (July 1974), "His [conducting] flowered into true greatness only after advancing age had halted his public cello playing," and in deed his Columbia symphonic discography from the Sixties includes performances of the Beethoven Eighth, Haydn Surprise, Mendelssohn Italian, Schubert Unfinished, and Mozart K. 543 and 550 comparable with the greatest from any source.

This Beethoven Seventh, taped at the 1969 Marlboro Festival, would be remarkable enough coming from any orchestra and conductor; from an ad hoc ensemble and a ninety-three-year-old maestro it is simply miraculous. It is in fact the first modern recording worthy of comparison with the 1936 Toscanini/New York Philharmonic version. There are naturally temperamental differences, but one en counters much the same grandeur, structural sense, and rhythmic vitality.

The imperious opening chords immediately recall the classic older recording, and the succeeding woodwind lines are molded and colored with the same imaginativeness and sense of impending drama. If the introduction seems a hairsbreadth too slow, it is interesting to recall that the original 78 is sue of the Toscanini/Philharmonic version contained an almost identical account; when the worn stamper of that disc side was replaced in 1942, a slightly faster alternate Side 1 from the same sessions was substituted.

Once Casals reaches the vivace, he sweeps through the 6/8 measures with imperious authority, never losing his rhythmic grip. Sonorities are always solid and planned from the bass up.

The Allegretto is a shade heavy for my taste, but once again Casals' unfailing sense of rhythm saves the day. Whatever the actual tempo, the stress is rightly that of an alla breve, and the feeling for phrasing and cumulative line is extraordinary. (A slight reduction of volume in this movement restores some of the delicacy and lightness lost through close miking.) The scherzo, done with full repeats, gets a robust account. Casals' slowdown for the assai meno presto trio is moderate, preserving the succinct, angular quality of the music-no "pilgrim's hymn" for him.

The finale simply carries the listener away irresistibly. As with the Toscanini/Philharmonic performance, the tempo is not particularly brisk, but the control is rock-solid, never rushing even at the strongest climax. The impact is truly colossal.

What distinguishes the Toscanini and Casals Sevenths is not merely rhythmic correctness, but rather the inspired fervor and spirit imparted to virtually every bar. The fifty-three-piece Marlboro Festival Orchestra may not be large by going standards, but it makes up for its moderate size by playing with out standing personality and concentration (the personnel list included first-desk players from the country's major orchestras and leading soloists and chamber musicians), as if mesmerized by the nonagenarian conductor. I suspect that anyone who hears this performance will be mesmerized too.

As noted, the sound is extremely close and lacking in truly soft dynamic levels. The right channel also sounded somewhat weak to me, with the timpani in particular under-recorded. (In addition, my pressing was a bit noisy.) Still, the reproduction is decent enough to permit this resplendent performance to make most of its effect.

A new Karajan Symphonie fantastique might not seem a pressing need and one can hardly complain of lacunae in his discography, which in fact includes an earlier DG stereo Fantastique. But if Karajan has ever made a finer record, I have not heard it.

His previous Fantastique was utterly depressing: gooey, structurally amorphous, lacking both characterization and urgency. The new performance has all the wonted Karajan/Berlin refinement of execution-but this time all their luxurious virtuosity is put at the service of the music.

From the first notes, sounded delicately from afar, yet tensile and affecting, Karajan realizes the synthesis of classical purity and demented fervor in this still revolutionary score. The first movement heaves with all the opium-tinged fermatas and tempo adjustments so painstakingly marked in the score, yet the ongoing line remains unbroken. The distant but miraculously clear reproduction captures every shimmering instrumental strand, at the same time af fording a walloping dynamic range.

The second-movement "Unbal" (done without the cornets that Berlioz added later) is again mercurial and lilting. The little fermatas in the violins' main theme are perfectly gauged, and the appearance of the idee fixe is exquisitely set against the little fragments from the movement's principal melody. The third-movement "Scene aux champs" is sheer poetry from beginning to end; Karajan brings off a slightly faster than usual tempo with magical effect. The quivering oboe-English-horn duet, the soaring, al most suspended strings, the anguished lower-strings framing of the kik fixe-surely these have never been played with such dramatic, yet subtle, effect.

The start of the "Marche au supplice" gave me momentary doubts: The Berlin brasses produce such a mellow, well-modulated sound, and the distant miking subdues the rasping overtones heard to such splendid effect in the recent Davis/Concertgebouw edition (Philips 6500 774, May 1975). But one quickly becomes aware of Karajan's rhythmic exactitude, and at the end he characterizes more vividly than I have ever heard the "decapitation" of the forlorn clarinet statement of the idee fixe, delaying the pizzicatos that depict the severed head just long enough for devastatingly final impact.

Karajan's Witches' Sabbath may be the most en lightening movement of all. He begins it eerily, with all the little effects calculated perfectly: The lower strings sound like gasps; the flute and piccolo are allowed to play their downward glissandos in spine chilling, but never vulgar, fashion. The chimes are rather similar in their impure, cobblestone-like sonority to the Davis/Concertgebouw counterparts and blend into the Dies Irae motif with sobbing, grief-laden restraint; from this point the movement is given a deliberate reading that nonetheless abounds with symphonic grandeur.

The scrupulous, musical Davis/Concertgebouw Fantastique (a substantial improvement over his earlier version, with the London Symphony) will remain the choice for those who insist on every repeat and the second-movement cornets, but I still miss the element of passionate drama. (At budget price, Beecham's Seraphim account, S 60165, is excitingly poetic, if shaggily played.) As a balanced re-creation of Berlioz' whole artistic vision, I find the new Karajan performance a sublime achievement, in a class with Monteux's Paris Symphony Fantastique and Toscanini's Harold in Italy.

Beethoven: Symphony No. 7, in A, Op. 92. Marlboro Festival Orchestra, Pablo Casals, cond. [Mischa Schneider, prod.] CO LUMBIA M 33788, $6.98.

Berlioz -- Symphonie fantastique, Op. 14. Berlin Philharmonic Orchestra, Herbert von Karajan, cond. [Hans Hirsch and Hans Weber, prod.] DEUTSCHE GRAMMOPHON 2530 597, $7.98.

--------------

Gagliano's Dafne: Music Drama in 1608

by Andrew Porter

A woodcut, c. 1500, by Jacopo Ripanda of Bologna shows Daphne, pursued

by Apollo, being transformed into a laurel tree.

A superior edition helps Musica Pacifica give a more satisfactory representation than the New York Pro Musica of the fourth opera.

AS OSCAR SONNECK once wrote of the Florentine Camerata, "They sought Greek drama and found opera... All the undercurrents of their time might have been converging towards opera, yet of them selves they would not have led to opera without the new and distinguishing element of dramatic musical speech." The first try was Dafne (1597), set in part by Corsi and then by Peni and Caccini. Opera itself we can date from Pen's Euridice (1600); and music drama, in just about all the senses of that term as it is used now, from the third opera (the second was Caccini's setting of Euridice), Monteverdi's Orfeo (1607). The fourth opera is Marco da Gagliano's Dafne (1608), composed, like Orfeo, for the Mantuan court and its excellent musicians. After a decade of operatic experience, the librettist of Milne, Ottavio Rinuccini, revised that first text he had given to Peni and Caccini. He amplified it, made it more dramatic, and linked more closely the two events of the action.

The first event is Apollo's battle with the Python.

(Originally, set by Luca Marenzio, it had been an intermezzo in a 1589 Medici festival production; verbally, scenically, and musically, the men who created opera were men who had worked on these intermezzos.) In the Gagliano version, there is a new chorus to accompany Apollo's fight and later a "re-play" of the match, in narrative and mime, enacted by a shepherd for the benefit of Daphne, who missed it. The second event, Daphne's metamorphosis into a laurel, takes place off-stage but is vividly described by Thyrsis. (The first Thyrsis, Antonio Brandi, had "wonderful diction, marvelous grace in his manner of singing, and did not merely make the words clear but by his gestures and movements imprinted on the soul an inexpressible something more.") A production of Gagliano's Dafne, given at the Spoleto, Corfu, and Caramoor Festivals in 1973, and in 1974 taken on a spring tour, was the swan song of the New York Pro Musica Antigua; the Musical Heritage set is a recorded version of that production. The Command set has its origins in an edition of the score made by James H. Moore (it came to the attention of Pro Musica, which, however, decided to prepare its own version; more about the two editions below), which was first performed by the UCLA Collegium Musicum in 1971, and then in 1975 by Musica Pacifica, with the cast of the recording.

I have never seen Dafne on the stage and have long wanted to, for it is a work in which the talents of stage designer, stage director, choreographer, and musicians should combine. The Python, for example, "should be very large; and if the designer knows how, as I have seen it done, to make it flap its wings and spit fire, it will be a still finer sight-especially if the man inside goes down on all fours as he creeps around." That sentence, like the one about Thyrsis, comes from Gagliano's long preface to his score, which was published in 1608. (Copies are rare, but there has been a facsimile reprint.) The preface is a fascinating and important document, which combines a brief ac count of the origins of opera with a review of the first performance, and a move-by-move, sometimes bar by-bar production book. The props man is told how to contrive a bough of laurel that Apollo can twine into a wreath without ridiculous effect. The director is instructed how players in the wings should be synchronized with Apollo's appearing to play his lyre.

He is warned not to confuse naturalistic chorus movement with dancing. The musical director is advised about balance and instrumental placement.

The singers are told not to indulge in too much deco ration: "In that way, the syllables can be shaped so that the words can be clearly understood. And that should always be the principal aim of a singer, when ever he sings, but especially when declaiming, for true delight is born from understanding of the words." In both of these Dafne performances, the actual expression of the words leaves something to be de sired. The singers pronounce them carefully and clearly but, except in a few instances, hardly bring them to life. One example: There is a moment when Cupid teases his mother about her affair with Vulcan, and Venus confesses that she blushed at the time. Neither of the Cupids invests "his" lines with the right merry twinkle, and only one of the Venuses, Maurita Thornburgh (Command), has the timbre of a rueful smile in her answer.

Ideally, one would like to hear interpreters of the Janet Baker caliber declaim this score. (Miss Baker as Venus or Daphne, Ileana Cotrubas as Cupid, Jon Vickers as Apollo, Fischer-Dieskau as Ovid could be the start of a strong cast.) Perhaps we will; in a world with two Dafne sets and two Navarraise sets, any thing is possible. Meanwhile, either of these recordings, delicately and sensitively if not very dramatically performed by clean, cultivated singers and deft instrumentalists, gives a fair notion of a work that is never less than attractive and in its final sequences--from Thyrsis' narration through the laments of Daphne's companions to Apollo's big aria-is very striking and affecting.

One set, however, gives a better idea of the piece than the other, and the reason lies not so much with the performers as with the edition. In the Pro Musica version on MHS, most of the opera is performed sometimes a fourth and sometimes a fifth above the printed pitch. The usual complaint against seventeenth-century operas when done today is that male roles for soprano and alto are growled out by tenors and baritones-in Monteverdi, in Cavalli. But in the MHS Dafne it's the other way round. To put it a little cruelly, there are moments when Apollo and Daphne become Donald Duck and Minnie Mouse.

This was done, according to George Houle's liner note, "for Daniel Collins" (though that doesn't ex plain why Ovid should be pushed up a fourth). Since Pro Musica had, in Collins (a countertenor), a re markable artist to play the role of Apollo, a case could be made for the transposition in the company's live performances; it is harder to justify it in the permanent form of a recording. Musica Pacifica en gaged, in Robert White, an Apollo of at least equal accomplishment and one who is in any case very much more effective by reason of his being a tenor.

The Venus also sounds more sensuous at the printed pitch. Both choruses, I think, are slightly too bouncy, too tripping in manner, not theatrical enough. Neither brings much excitement to the combat scene.

The Musica Pacifica performance is on the larger scale. Paul Vorwerk conducts an ensemble of fifteen players, while Houle with the Pro Musica has only five. Gagliano asked for a chorus of sixteen or eighteen; Musica Pacifica has ten, in addition to the nymphs and shepherds with solo parts; Pro Musica does not specify but evidently has fewer. James Moore has scored after the model of the pastoral scenes in Monteverdi's Orfeo; he has violins at his disposal and uses a double bass as foundation for the full chorus. Houle has basically two recorders over continuo. Both discs are clean and well balanced.

The Command set is complete and there is only one addition: The Moore edition borrows a sinfonia from Salomone Rossi. (Gagliano mentions a sinfonia, but there is none in the score.) Houle omits three strophes of the prologue, referring to the Duke and Duchess of Mantua, and two of the finale, and has read the verses of the chorus "Nud'arcier" in the wrong order. As prelude, he supplies a trio sonata, II Corisino, by Francesco Turchi. And he has added an aria from Gagliano's Musiche of 1615 to the first scene (it is not well enough sung to justify its inclusion and in any case is unwanted); also a segment of a Frescobaldi toccata, as entrance music for Daphne, and J. J. van Eyck's pretty variations on "When Daphne did from Phoebus fly," to accompany Daphne's flight. Both editors have drawn on notes about vocal distribution found in a copy of the score in the National Library, Florence; where the results differ, Moore's are the more convincing.

With each set there is a libretto and translation.

Neither is flawless, but the Command scores heavily on two counts: It indicates which passages were added by the librettist for Gagliano's new setting of his text; and it prints the libretto as verse, observing the proper lineation.

Dafne is not another Orfeo. There is nothing like Monteverdi's genius for enriching the declamatory style with the closed forms of his day-arias, duets, choral dances, madrigals, instrumental ritornellos- thus setting up those tensions, between dramatic declamation and "purely musical" concerns, that underlie the whole history of opera from his day to ours. Gagliano does use these forms but, except in his final scene, less certainly. All the same, Dafne is a mi nor milestone in the early history of opera (after yet another transformation, and translation, the libretto served for the first German opera, Schutz's lost Daphne) and is well worth attention.

----------

Daewoo: L a Dafne.

(1)

Mary Rawcliffe (s)

Maurita Thornburgh (s)

S AJ Harmon (s)

Dale Terbeek (c1)

Robert White (t)

Myron Myers (bs)

Susan Judy (s)

Mary Rawchlte (s)

Anne Turner (s)

Shepherds Hayden Blanchard (t)

Jonathan Mack (t)

Myron Myers (bs)

(1) Musica Pacifica, Paul Vorwerk, cond. (ed. James H. Moore). [Kathryn King, prod.]

COMMAND COMS 9004-2, $6.98 (two QS-encoded discs, automatic sequence).

(2) New York Pro Musica, George Houle, ed. and cond.

[James Rich, prod.]

MUSICAL HERITAGE MHS 1953/4, $7.00 (two discs, automatic sequence; Musical Heritage Society, 1991 Broadway, New York, N.Y. 10023). Daphne Venus Cupid Thyrsrs Apollo Ovid Nymphs (2)

Christine Whittesley (s)

Christine Whiffesley (s)

Elizabeth Humes (s)

Ray DeVoll (t)

Daniel Collins (ct)

Ray DeVoll (1)

Anne Tedards (s)

Nancy Long (ms)

David Britton (t)

Ben Bagby (b)

Rodney Godshall (bs)

-----------------------

The Command set in quad: From a dramatic point of view especially, the capabilities of the QS matrix system are used in an interesting, if not over whelming, way in this recording. When circum stances make antiphonal effects possible, they are certainly there-and with no doubt about where the participants are located. There is not, however, much actual movement of the singers while they are singing, and this may well reflect the rather static staging that prevailed in seventeenth-century opera.

But in any case, the interplay between the various combinations of voices and instruments more or less surrounding the listener is very pleasant.

If there is any weakness in the sonic image presented, it is that somehow the four channels do not quite add up to a believable over-all space. Per haps because of the generally high ratio of direct to reverberant sound in the recorded "space," the characters do not seem to sing to each other-only to the listener, and each via a separate pipeline. But this effect (though it can be exaggerated somewhat by a Vario-Matrix decoder) is subtle. The musical sound is clear, and the listener is made privy to all the niceties of interpretation.

-- HAROLD A. RODGERS

--------------------

(High Fidelity, Feb. 1976)

Also see:

Link | --Link | --Link | --Link | --Link | --Marantz turntables