A High-Class Musicological Cops-&-Robbers Tragicomedy in Three Acts Drawings

The Great Mozart-Beethoven Caper: Or, Does the Pierpont Morgan Library House Stolen Goods?

by Paul Moor

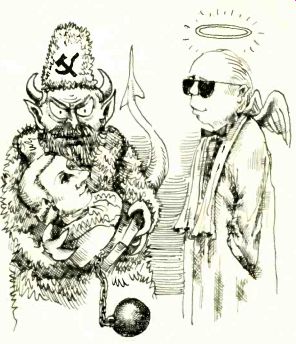

Drawing by by Bruce MacDonald

---Paul Moor, writer, musician. CBS broadcaster, and long time correspondent for HIGH FIDELITY and MUSICAL AMERICA, has lived in Germany for the past twenty-five years. ---

Act I

OUR STORY OPENS in East Berlin on the first of May, 1951. As on May Day in all Socialist countries, a carnival atmosphere prevails; schools and offices have closed, enabling the enormous political demonstration to attract as many citizens of the German Democratic Republic as possible to the Marx Engels-Platz, either as marchers or as spectators.

Around the corner, in the spacious old boulevard Unter den Linden, the imposing buildings stand quiet and empty as the crowds swarm past, in the balmy spring air, on their way eastward to the big square. Cater-cornered from the State Op era and next door to the university stands the Ger man State Library, Berlin's equivalent of Washington's Library of Congress. Like the others, it is empty-or, at least, almost. One man there this morning has urgent business. His colleagues, had they not the day off, would recognize and defer to him as Dr. Joachim Kruger-Riebow, director of the library's music section and its literally priceless autograph manuscript collection. As usual, he carries one of only two existing keys to the safe that contains the legendary collection of musical manuscripts.

His colleagues know the forty-one-year-old librarian as a passionate lover of music, as a bibliophile-indeed, his passion justifies the term "bibliomania"--and as a creditable performer on three instruments. He has acquired a reputation as a staunch and loyal member of the governing Socialist Unity (Communist) Party and as the heart-and-soul secretary of the Society for German-Polish Friendship; he figured actively and importantly in the return to Poland of Chopin manuscripts stolen during the Nazi occupation. (He speaks Polish well, not to mention modern Greek.) It did him no harm when, eight months ago, a government minister--a party comrade, naturally recommended his promotion from a lowlier position at the library to his present post, one of the most important and distinguished of its kind in the world.

The May Day crowds, on pleasure bent, pay no heed when a truck backs up to a side-street en trance of the German State Library. Wasting no time but attracting no attention by undue haste or furtiveness, the driver and the music librarian load three or four packing cases. Minutes later, with the librarian as passenger, the truck crosses the sector boundary into West Berlin. (The Berlin Wall will not go up for another decade.) Our scene shifts now to Cologne airport four days later, as Dr. Kruger-Riebow arrives from Berlin. His baggage includes one of the packing cases.

When a lubberly attendant drops it, it bursts and, before the suspicious regard of a uniformed customs inspector, a cascade of obviously old manuscripts pours out onto the floor. The inspector asks pointed questions. The librarian, however, has the necessary official identity papers to confirm his claim to the exalted scholarly nature of his office.

He tells the staring inspector he intends to deliver the manuscripts to the Beethoven House in nearby Bonn, the master's birthplace. The inspector retains some mistrust, but the obviously official documents have exerted their customary magical effect upon the German bureaucratic mind. He al lows his suspect, with his patched-up baggage, to pass, addressing him, with reflexive deference, as Herr Doktor.

At the Beethoven House, its director Dr. Joseph Schmidt-Gorg receives his East Berlin colleague politely. When he learns what he has brought with him as a get-acquainted present, politeness gives way to the nearest thing to utter, lyric rapture a proper musicologist can experience. Dr. Kruger Riebow says that at the risk of his life he has just barely, in time's nick, snatched these priceless treasures out of the sweaty, uncouth clutches of the Russians, who, he says, were planning to re move them to Moscow in the imminent future. Dr. Schmidt-Gorg, touched-nay, moved-by his visitor's selfless, musicological heroism, promises the absolute discretion his visitor demands. Dr. Schmidt-Gorg gladly prepares and hands over an itemized receipt for this overwhelming, totally un expected windfall.

As the refugee bibliophile returns to the airport, he muses poignantly, perhaps, about all of the other treasures that, for one reason or another, he has left behind in the Soviet sector of Berlin: by Bach alone, the St. Matthew Passion, the six Brandenburg Concertos, the first half of The Well-Tempered Clavier, and the Orgelbfichlein; two acts of Mozart's The Marriage of Figaro; the Brahms D minor Piano Concerto; Beethoven's Piano Sonata, Op. 111; Schubert's Goethe songs; Schumann songs, by the volume-to mention merely a tiny se lection of the gems to which he had had exclusive and unrestricted access.

Even so, he has not done too shabbily by the Beethoven House. With quiet, decorous, musicological satisfaction, Dr. Kruger-Riebow, who has courageously turned his back on prestige and position, shows the still slightly suspicious customs inspector his receipt from Dr. Schmidt-Gorg. Among the items listed are dozens of letters written by Buxtehude, Czerny, Mahler, Mendelssohn, Meyerbeer, Richard Strauss, and Cosima Wagner; two musical manuscripts each of Glinka and Debussy; Handel's Salve Regina; twenty-seven Beethoven manuscripts, including sketches for the Pastoral Sonata, Op. 28, Missa Solemnis, String Quartets Nos. 12 and 16, Opp. 127 and 135, respectively; and the Eighth and Ninth Symphonies; and, most staggering of all, 137 of the extant 139 "conversation notebooks" to which the deaf Beethoven, during the last decade of his life-a decade that saw the creation of his supreme masterpieces-had to re sort in order to communicate.

Now we cut to New York, where in September 1951 The New York Times publishes a story date lined Berlin: "The priceless 'conversation books' recording Beethoven's talks with his friends dur ing his final years of deafness have disappeared from the former Prussian State Library on the Un ter den Linden in the Soviet sector of Berlin. Rumor of this loss was confirmed when Carleton Smith, director of the National Arts Foundation, was told he could not see them when he visited the collection yesterday....

"One of the library's senior curators, Dr. Joachim Kruger-Riebow, disappeared late this spring at about the same time that the absence of the precious five-foot shelf of notebooks was first noted. Dr. Kruger-Riebow, who had the reputation of being a loyal Socialist Unity Party member until he absconded, is presumed to be working his pas sage home with these treasures of Germany's musical heritage." Irony of fate! The story breaks in distant America before it does in Germany--and how many musicological scholars working in Germany read The New York Times?

Act II

Eight years have passed. Our anti-Communist li brarian has settled down to unmarried life in West Berlin with a lady friend named Reichwein, who helps him run a rare-books business. Eccentricity, not unknown in this profession, here runs rather rampant. The business bears the name Bayreuther Musik-Antiquariat, although it operates out of Berlin and has only a post-office box in Bayreuth.

It publishes an annual catalog, about a hundred pages thick, which makes bibliophilic mouths wa ter. Prices on individual items range up to about $5,000. Orders come in from as far away as Japan.

One such order, in September 1959, is placed by the Shiseido company in Kyoto, which pays al most $6,000 down. This necessitates a business trip for our hero. On September 16, in Hannover's Mu nicipal Library, Dr. Kruger-Riebow turns up Ludwig Erk's three-volume Deutscher Liederhort.

Next morning, in the Duke August Library in Wolfenbuttel, he finds an early volume of Fresco baldi, another rare book of late sixteenth-century Italian music, and a 1514 Buchardus volume, with a combined worth of $4,000 to $5,000. He proceeds to Gottingen, where he goes to the university library's catalog room. A young woman doing re search there seems to regard him with interest but presently leaves. On the open shelves he finds the 1956-57 and 1957-58 editions of American Book Prices Current. After he has passed the barrier, but before he has left the building, a policeman de tains him. Inside his coat, under his arms, he has the two books, worth only about seventeen dollars each. The policeman listens impassively to his stammered explanation that he had had to go to the toilet but had not wanted to interrupt his scholarly research.

As a matter of routine, the police check his room at the Gebhards Hotel. There they discover not only the swag from Hannover and Wolfenbuttel, but also a portable chemical workshop for the era dication of library stamps and other identifying markings. The Gottingen police alert their Berlin counterparts, who find in Dr. Kruger-Riebow's digs, among many other interesting articles, liter ally thousands of slips of paper, each one bearing the title of a rare book and the name of the library where one might consult it. The Gottingen police fling "Dr. Joachim Kruger-Riebow" into the local slammer. A guard, noticing that whenever he enters the scholarly guest snaps smartly to attention underneath the cell window, remarks his evident familiarity with German jailhouse procedure.

About six months later, on March 24,1960, "the music dealer Joachim Kruger, born on February 10, 1910, in Wust, county of Jerichow," as the court record baldly identifies him, stands accused be fore a Gottingen judge. The prosecutor charges him with theft in the three cities in as many days, with fraud against Shiseido, with use of falsified identity papers, and ( Germany takes such things seriously) with unauthorized use of the academic title Doktor.

The trial strips Joachim Kruger to his authentic identity. He never, it now transpires, even at tended a university. In fact, he lacked two years of finishing even the Gymnasium in Stendal. Returning to civilian life in 1945 from a Waffen-S.S. sabotage batallion, he joined-at least so he says-the Gehlen Organization, originally Hitler's espionage apparatus against the Soviet Union that the Americans took over almost intact when the war ended.

As Kruger tells it, the postwar spooks gave him his phony identity papers, including the Doktor fillip and the less commonplace surname Riebow, to camouflage his problematical military past before assigning him to spy in and against East Berlin.

Implacably the court confronts him with the record of his previous iniquities, undreamed of by those who originally hired him to work in the state library. His record in Magdeburg shows he had been sentenced on April 23, 1936, to two and a half years, on March 3, 1938, to six months, and on December 9, 1938, to three months; rather mysteriously, on an unspecified date in 1938, a court in distant Konigsberg (now Kaliningrad, U.S.S.R.) hit him with an unspecified prison sentence. These cases involved such human failings as forgery, fraud, embezzlement, and theft. The Gottingen court, taking into account the full recovery, un damaged, of the loot involved in this trial, lets Kruger off with a mere eighteen-month sentence.

Act III

The trial arouses curiosity and ambient interest in many of the other state library knickknacks that Kruger thoughtfully chose that day nine years earlier when he chose freedom. Dr. Karl-Heinz Kohler, a distinguished real musicologist who re placed Kruger in the state library, had begun in 1956 to advertise for the stolen boodle-the Beethoven notebooks, Mozart's Piano Sonata in A minor, K. 310, etc.-in such professional journals as Die Musikforschung, published in the West German city of Kassel. Bit by bit, manuscript by manuscript, it gradually becomes clear that the two or three original packing crates that Kruger did not deposit in Bonn in fact served him as the original capital with which he established his flourishing worldwide book business.

A number of honest music librarians in various countries, innocent purchasers from middlemen of items Kruger had purloined and then sold with a forged accompanying letter of authentication on stolen state library stationery, voluntarily and without any to-do return them to Dr. Kohler.

Among them is Harold Spivacke, director of the Library of Congress' music division, who returns a Haydn autograph letter that had originally stuck to Kruger's fingers.

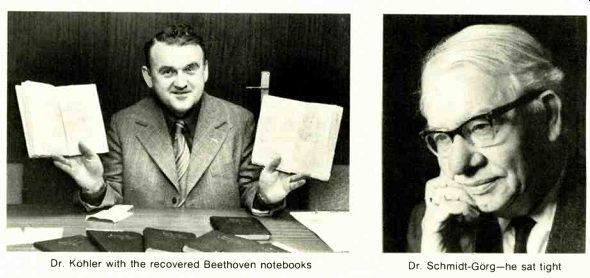

German-speaking musicologists and librarians customarily study such journals as Die Musik forschung as assiduously as fundamentalist ministers study the Bible. In Bonn, however, Dr. Schmidt-Gorg remains mum. Some word of the Beethoven House's unsolicited acquisitions has trickled out, but at least to one inquiry-the year before the Gottingen trial brought everything into the open-from Hildegard Weigel, a West Berlin research musicologist, the director replies: "Of Beethoven conversation notebooks in Bonn nothing is known to us." Acting upon press reports of Kruger's trial, Dr. Kohler writes to Dr. Schmidt-Gorg. In reply he gets an orderly four-page typewritten list confirming the whereabouts for the past nine years of Kruger's one packing case full of loot. On July 6, 1960, the state library's Generaldirektor himself writes to Schmidt-Gorg, formally requesting him to return the booty.

Silence.

On August 26 he tries again and on September 13 receives a reply. Dr. Schmidt-Gorg defends his position based on the fact that the Prussian State Library, the original owner of the treasures he holds, ceased to exist in 1945 along with the Ger man state of Prussia; the library changed its name first to the Public Scientific Library, then to the German State Library. Schmidt-Gorg, on his unique and priceless windfall, sits tight.

Dr. Kohler, ordinarily a mild and mannerly scholar, reaches the end of his tether and of his patience, and goes onto the offensive. In the East Berlin popular weekly Sonntag on February 26, 1961, he publishes a thorough, aggressive documentation of the entire Mozart-Beethoven caper, including the full text of Schmidt-Gorg's letter, which he calls "insulting"; at two other points he also em ploys the term "insult," the scholarly equivalent of a glove slapped with deliberation across the adversary's chops.

Conscientious

West Germans, notable among them the composer Wolfgang Fortner, respond to Dr. Kohler's broadside. They proclaim, in essence, that Cold War anticommunism must not blind honest, respectable Germans' eyes to common thievery. A face-saving musicological bucket line goes into action: The Beethoven House passes the boodle along to West Berlin's Academy of the Arts, which passes it along to the Academy of the Arts of the German Democratic Republic, which on May 14, 1961, after ten years and thirteen days, re turns it to its rightful owner, the German State Library.

-------------

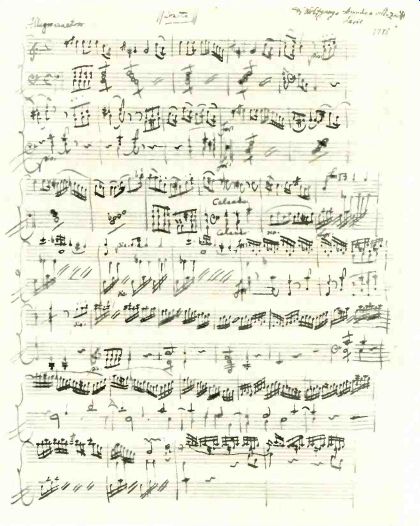

--- This is the opening manuscript page of Mozart's ever- popular A minor Piano Sonata, K. 310, which currently re poses in New York's Morgan Library on loan from the Robert O. Lehman Collection. Scholars will note that Mozart wrote the beginning of the left-hand part in the tenor clef. Criminologists will note that the manuscript was part of Joachim Kruger's swag.

--------- Dr. Kohler with the recovered Beethoven notebooks Dr. Schmidt-Gorg-he

sat tight

Meanwhile, back at the Gottingen courthouse, poor Kruger's troubles, far from over, seem scarcely to have begun. He stands totally exposed--at least, a number of anxious musicologists and librarians hope so. On July 6, 1961, a month be fore the end of his eighteen-month sentence, Gottingen's public prosecutor finally gets around to charging him with all the peccadillos that he had committed before the three for which he was busted. During this one-day second trial, Kruger testifies freely about ripping off the Beethoven notebooks, the Mozart K. 310 Sonata, and so on, still desperately clutching his by now thoroughly waterlogged lifesaver that he did it all to save such German cultural treasures from Russian Communist barbarism. The Gottingen Kriminalpolizei says its investigations show that, aside from the Bonn deposit, Kruger realized "enormous income" from his swag.

For theft, West German law foresees a maximum sentence of five years' imprisonment. The statute of limitations on theft, however, comes into force five years after the deed. And 1961 minus 1951 equals 10. On these charges, for offenses of in finitely greater gravity than those on which the first Gottingen trial convicted him, Kruger goes scot-free.

On August 18, 1961, Joachim Kruger walks out of prison. Five days earlier, the German Democratic Republic had built that darling wall across Berlin, an architectural accomplishment that did not re main without effect upon such little spirit of give and-take as existed between the two Germanys up to that time. Had that event come but a few months earlier, prior to the bucket-line operation, who would have possession of the stolen property today? Kruger settles down in Gottingen, and on February 9, 1962, the court has him up again for petty shoplifting but a month later drops the charges. On March 25, 1963, comes another such accusation.

Epilogue

If you wonder what became of that Mozart piano sonata, I have a modest scoop to report. You can find it, as of this writing, in the Morgan Library in New York. The Morgan has it on indefinite loan from the opulent collection of Robert O. Lehman, a producer of musical films and scion of the banking Lehman family. He bought the sonata in 1963, allegedly unknowing, from Rudolf Kallir, vice president of the American Mannex Corporation ("I'm in the steel business: s-t-e-e-l") and father and father-in-law, respectively, of noted pianists Lilian Kallir and her husband, Claude Frank. Kallir thus far prefers not to say where he got it. On January 28, 1960-three years before he unloaded it onto Lehman--The New York Times reported Kallir as saying "that he had acquired it from a 'well known dealer here' in 1955. He said he had received a purported authorization of sale ... [and that] he had made his purchase of the Mozart item 'in good faith.' " Now, Lehman may sue Kallir, Kallir may sue God knows whom, but as for Kruger, fateful circumstance militates against anybody's suing him.

That day in 1963, when the Gottingen police went to fetch him, he seemed to have disappeared into thin air.

Should you chance to read these lines, Joachim, no matter where, stay in bed with your hat on.

Dedicated to Robert O. Lehman, with compassion and with the consoling hope that he, as a film producer, will recognize a hell of a story.

-------------

(High Fidelity, March 1977)

Also see: