THE DISCWASHER GROUP OF COMPANIES which produce and distribute quality audio products present:

HIGH FIDELITY's 100 Years of Recording

A series of four original acrylic paintings

by Jim Jonson

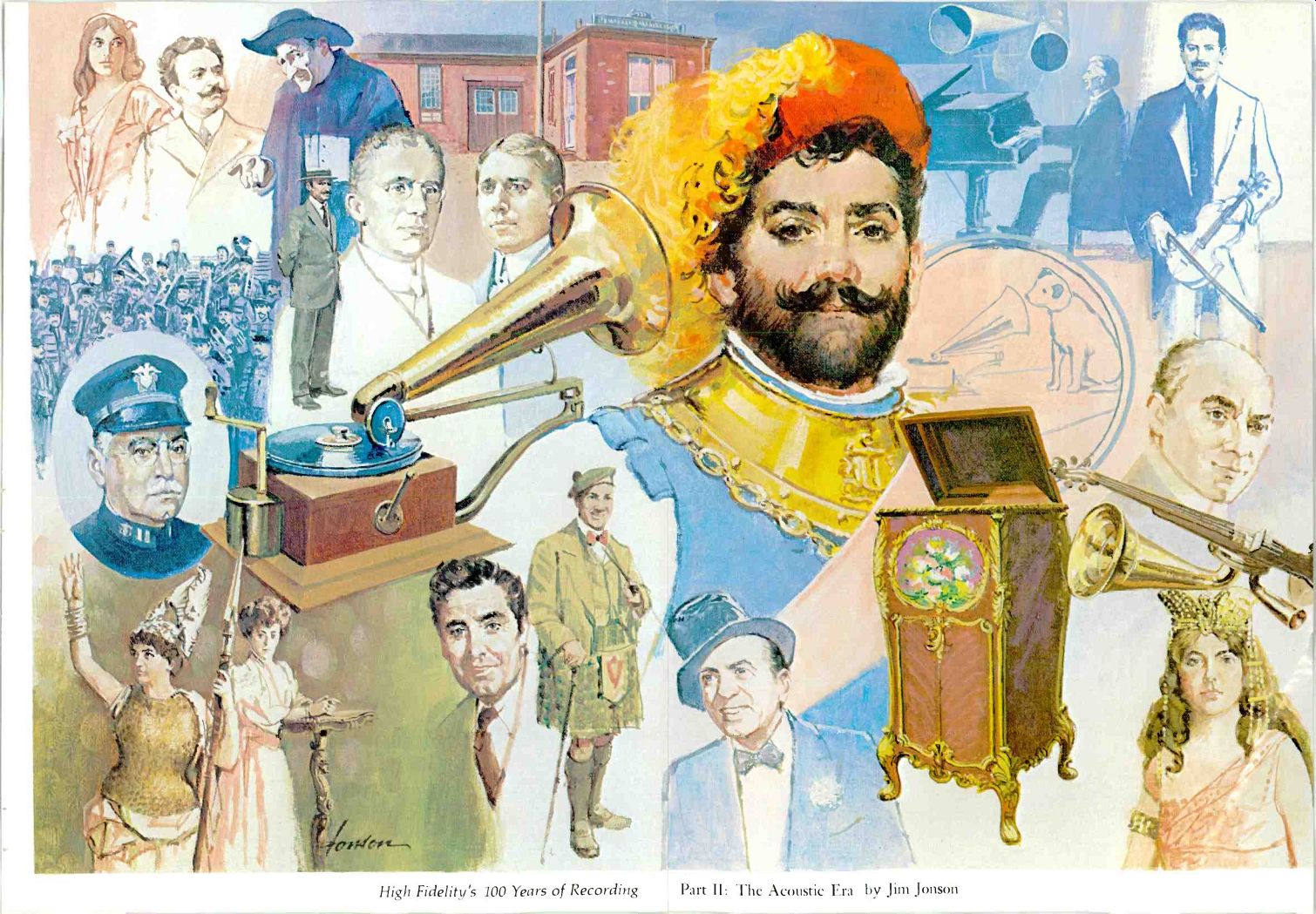

Inspired by the centennial of the phonograph and planned and commissioned by HIGH FIDELITY'S editors, the series depicts the development of recording through its leading figures in music and the recording business, its dominant means of sound reproduction, and its principal innovations in audio technology. The first of the four, "The Cylinder Era," appeared in February; the remaining two will be published later this year.

Jim Jonson, a Connecticut resident, has produced paintings for Saturday Evening Post, Sports Illustrated, Fortune, Reader's Digest, Boys' Life, and other journals and has fulfilled commissions for corporations ranging from Capitol Records to American Airlines and the Ford Motor Company. His work has been exhibited in the Denver Art Museum, Art Museum of Sport, and the Los Angeles County Art Museum, among others, and his one-man shows have been seen in many major galleries. A portfolio of Mr. Jonson's drawings and paintings was recently published by Prentice-Hall.

The Discwasher Group is proud to present the second of this distinguished artist's portrayals of "100 Years of Recordings."

Part II: The Acoustic Era

High Fidelity's 100 Years of Recording Part II: The Acoustic Era by Jim Jonson

The Acoustic Era -- March 18,1902, is a seminal date for the disc phonograph--or gramophone as Emile Berliner called it and as it still is called in most of the world. On that day the up-and-coming tenor Enrico Caruso, who with the gramophone dominates Jim Jonson's painting of the era (roughly the first quarter of this century), made his first recordings in Milan. A year later he was a major international opera star; a decade later virtually every major musical star had made discs and the cylinder record was in rapid decline. Caruso, costumed here as Meyerbeer's Vasco da Gama, was to record exclusively for Victor Red Seal (its "Nipper" logo appears behind him) from 1903 to his death in 1921, the acoustic recording technique favored the human voice--and Caruso in a sense "made" the phonograph because of his exceptionally phonogenic voice--not all the Red Seal stars were singers. Ignace Jan Paderewski (continuing clockwise from Caruso's hat) was overshadowed in sheer technique by a number of other recording pianists, but his reputation as Polish patriot, statesman, and man of letters made him, perhaps, the most famous. Similarly, Fritz Kreisler overshadows other violinists partly because of his long career and his many popular compositions-some of which created something of a scandal when it was learned that they were not by the "old masters" in whose style Kreisler had written them.

Conductor Landon Ronald, later knighted for his services to music, was an important early acquisition of the Gramophone Company, primarily because his wide acquaintance in musical circles was critical in persuading many stars to record.

The orchestra, however, posed severe problems to the recording horn, which responded adequately only to nearby sounds. The stringed instruments in particular could not be picked up realistically in large groups. Some companies substituted brasses; others adopted the Stroh violin, whose small, solid sounding board replaced the body of the instrument while metal horns focused and directed the sound.

Beside the Stroh violin is a particularly elegant variant of the Queen Anne Victrola, which--with its totally enclosed reproducing horn--made the phonograph unequivocally at home in the best-appointed parlors. The Queen Anne models and the Red Seal discs together led in establishing the social acceptability of recorded music.

While most of the prestige-label artists were European, a few were native products. Among the most eminent was alto Louise Homer (bottom right, as Amneris). In popular music, however, indigenous artists like Ted Lewis (in top hat) were the rule and imported entertainers like Sir Harry Lauder (in kilt) the exception. A few, like John McCormack (next to Lauder), cut across all national and musical boundaries.

McCormack--young, unknown, and poor in 1904--was delighted to step before the recording horn. Established artists often were not. The "legendary" soprano Adelina Patti (continuing to the left of McCormack), already in her sixties and retired, was persuaded to entertain the equipment and its operators in her Welsh castle in 1905. Lilli Lehmann was almost as old (she had sung in the first Bayreuth season in 1876) and as legendary, and even more versatile; her Odeon discs of the period range from the bel canto to the heroic.

Until adequate symphonic recordings could be managed, the brass band offered the most stirring sounds to be had on Berliner's discs, as it had on Edison's cylinders. But though John Philip Sousa's band recorded extensively for both, he openly attacked both (see HF, November 1973) as spoilers of musical amateurism and appreciation; the juxtaposition of Sousa's face with Berliner's gramophone may be taken equally as confrontation and partnership.

The small full-length figure (he was, in fact, tiny) is Fred Gaisberg, who pioneered as producer, recordist, and a&r man. He first recorded Caruso, Patti, Chaliapin, and many others. Looming beside him are the faces of Emile Berliner himself and Eldridge Johnson, originally Berliner's supplier (from the Camden, N.J., plant in the background) of spring--wind motors but ultimately the man who developed the Victor empire from Berliner's gramophone.

But, as Johnson understood, it was the stars-particularly the opera stars-who made the Victrola the Kodak of American phonography.

Soprano Geraldine Farrar (shown at upper left) was the first American operatic superstar; in the Twenties her fans were known as Gerryflappers.

Tenor Fernando de Lucia (some of whose European recordings were pressed here by Victor) not only was famous as a bel canto singer, but was director of the Phonotype Company, for whom he recorded both ll Barbiere di Siviglia and Rigoletto complete. Feodor Chaliapin (shown as Don Basilio in Barbiere) was probably the most celebrated bass of the era.

-ROBERT LONG

-------------

(High Fidelity, Apr. 1977)

Also see: